From its Early Nineteenth Century Origin to a Seventy Year Association with Everton FC

Mike Royden

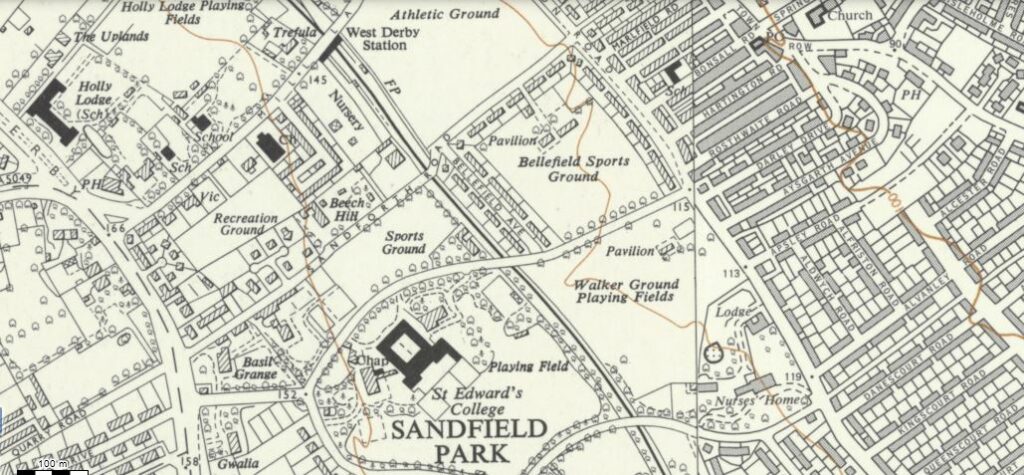

When Everton finally left Bellefield for the last time on 9 October 2007, it brought to an end an eight-decade association with the training complex which commenced in the 1930s. Previously, the senior side had utilised a variety of grounds, including Stanley Park and Walton Stiles, but from the turn of the century, training was centred on the Goodison pitch and the adjacent training ground behind the Park End stand. But how did the club come to use Bellefield and what was the estate originally used for?

Early history

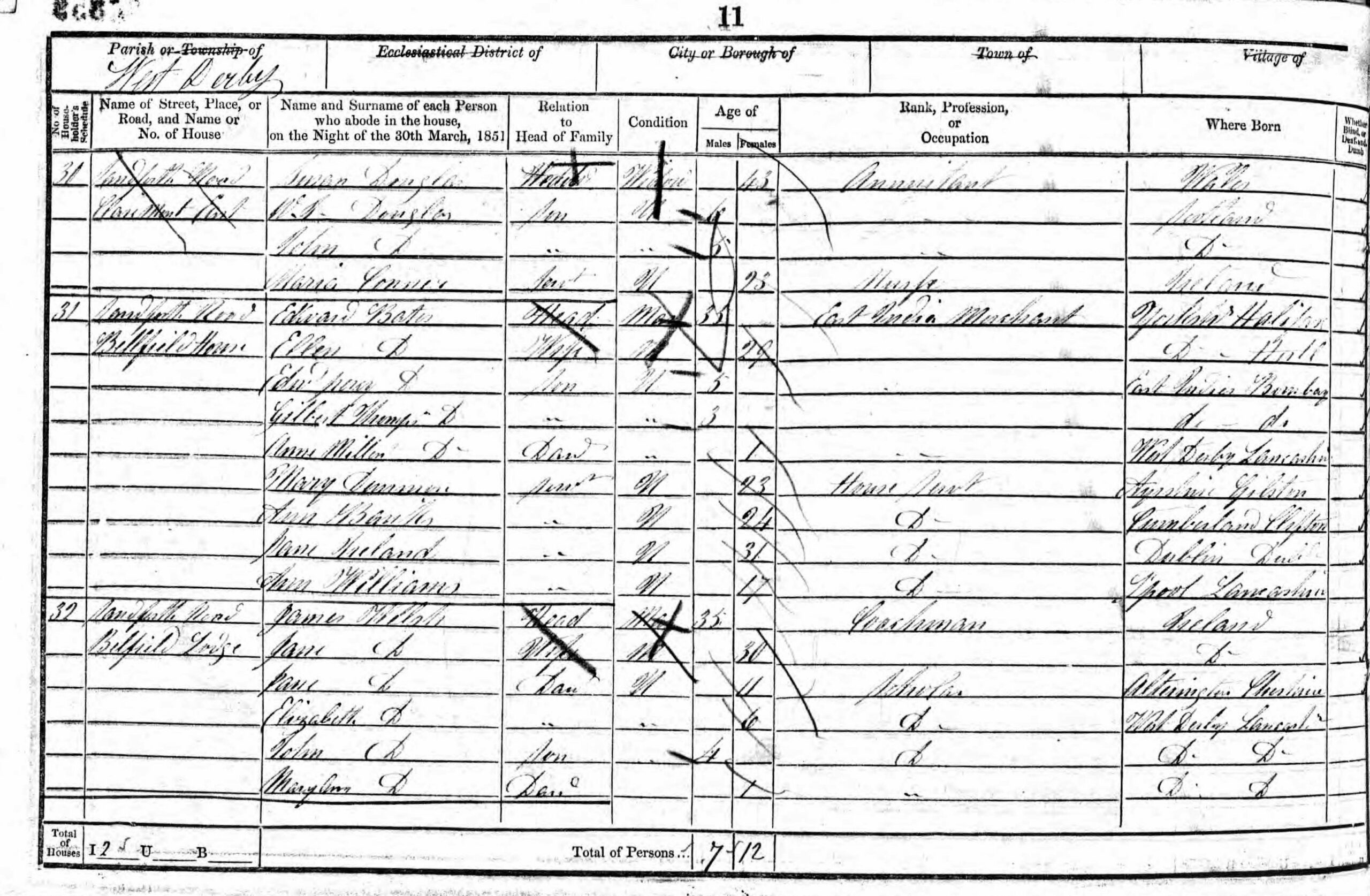

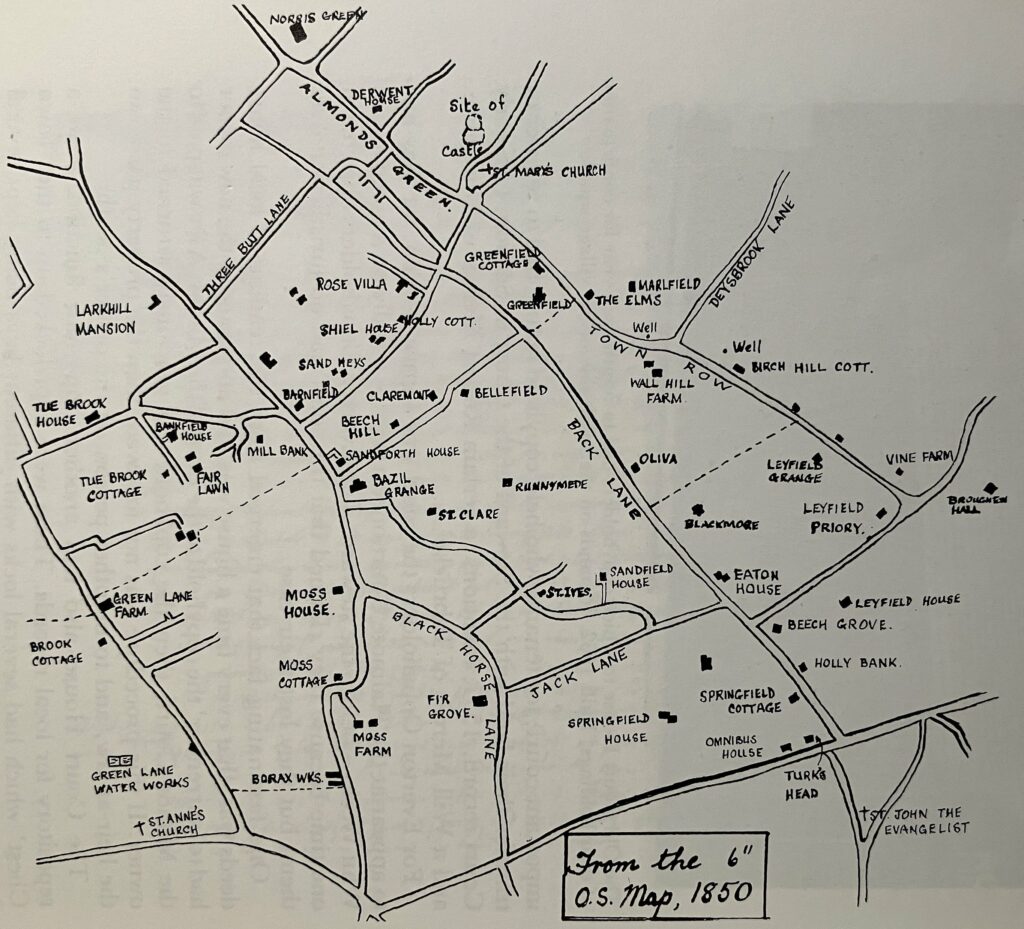

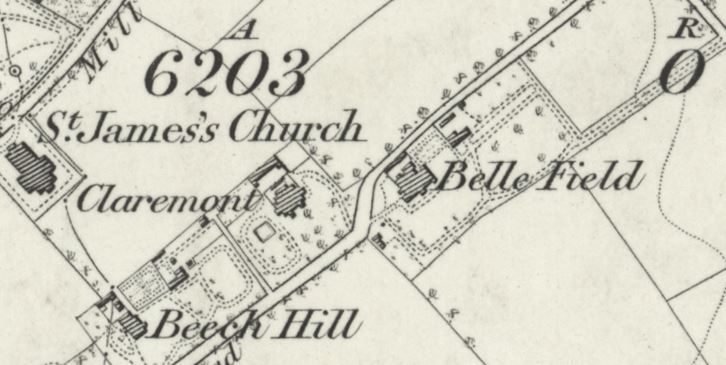

As the nineteenth century merchants of the expanding port of Liverpool grew wealthier, they sought large mansions with extensive estate in the surrounding hinterland. The gothic mansion of Bellefield owes its origins to such a desire, and was constructed in the 1820s, the first owner being Spencer Jones, an accountant partner in the iron foundry business of Bally & Jones of 4 Salthouse Lane in Liverpool. He was still recorded as the owner in 1838,(1) but by 1841 he had moved to Tranmere,(2) and Vincent Higgins, an Iron Merchant – and no doubt an acquaintance of Jones – was living in Bellefield.(3) Higgins’ stay was short, as in 1845 he was living in Rose Villa, Tuebrook, and by 1851 he too had departed over the water, for Clifton Park, also in Tranmere.(4)

(John Cooper & David Power, The People of West Derby (1988) p.201)

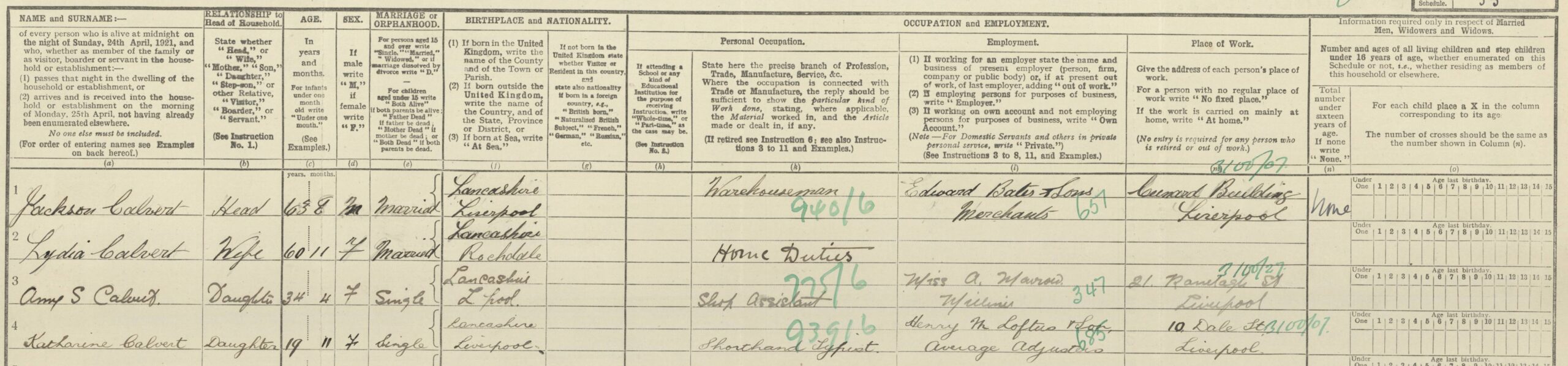

Bellefield was then purchased by Edward Bates, the son of Joseph Bates, an East India merchant of Halifax. In 1835, Joseph, who had been working to build up the business in Calcutta, returned to England to set up an office in Liverpool as an import/export merchant. His son Edward Bates (1816-96) was sent out to Calcutta in 1833 to work in the firm and to gain a broad business experience. Edward married in 1836 and returned to England in 1838, but in 1840 he went out to India again, this time to Bombay, where he established a mercantile house similar to the family operation in Calcutta. However, his wife Charlotte (nee Umfreville-Smith) became ill and they decided to return once more to England, but she died on 28 May 1843 while at sea on the Maitland.

Back in England, he married Ellen Thompson on 25 June 1844, daughter of Thomas Thompson, a Hull merchant and shipowner, and returned to Bombay, where he remained until 1848. His father died in 1846, and whereupon he returned to Liverpool to oversee their ship chartering business trading to Bombay, purchasing his own second-hand vessel a short time afterwards. With offices now in Liverpool, London and Bombay, over time he gradually built up his fleet of vessels and expanded his trading area, and by 1870 he owned a fleet of fifty-one, a figure that was later expanded to 130 ships. Subsequently, his sons Edward Percy Bates (b.1845) and Gilbert Thompson Bates (b.1847) became the managing partners in Edward Bates & Sons based at New Quay in Liverpool, enabling their father to focus on his political career. On entering politics as a Conservative, he represented Plymouth between 1871 and 1880, and again from 1885-1892 until his retirement. Disraeli compensated Bates for his disappointment in losing his seat in 1880 with a baronetcy. He was knighted as ‘Sir Edward Bates of Bellefield, baronet.’

(from John Cooper & David Power, A History of West Derby (1982). p.208)

Despite his success in business, his abrasive character soon earned him the moniker ‘Bully Bates,’ not least among the Liverpool crews and staff under his employ. He never endeared himself to locals, having never attempted to ingratiate himself into society, nor into local matters through politics, or benevolence, in a manner common among his contemporaries.

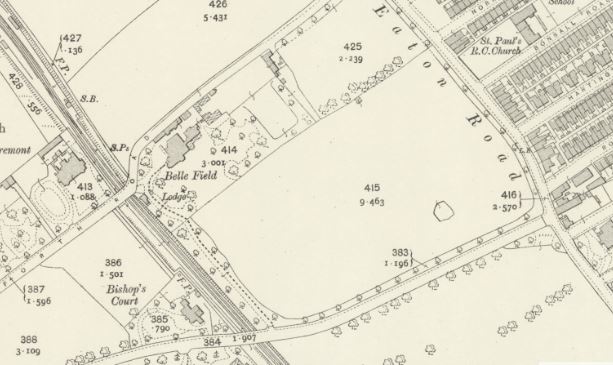

His reputation in West Derby never recovered after one particular action – he built a tree-lined carriageway from Bellefield to North Drive, Sandfield Park, complete with gates. When he asked the permission of the residents of Sandfield to use the Park as an entrance, he was told he could, as long as he paid the estate dues like everyone else. He refused, and permanently locked the gates to the carriageway.

By the 1880s, he was spending more time at his residences in Manydown Park, Hampshire, and Gyrn Castle, Llanasa, in Flintshire, but following the construction of the Cheshire Lines Railway close to Bellefield, the house was left unoccupied by the Bates family after 1884.

Sir Edward retired in 1892 and died shortly afterwards on 17 October 1896 at Manydown. He was succeeded by his son Sir Edward Percy Bates, 2nd Bart. (b.1845) who became chairman of P.S.N.C. as well as the Bates firm. He died unexpectedly of pneumonia in 1899 at his home in Beechenhurst, Allerton. The management of the family business and residences, including Bellefield, was inherited by his eldest son, Sir Edward Bertram Bates, 3rd Bart. (b.1877). In 1902, he travelled to India to see how the Indian operation was performing, and to take a holiday, but unfortunately, he caught enteric fever and died there in 1903.

His brother Sir Percy Elly Bates, 4th Bart. (1879-1946) succeeded, who proved to have greater business acumen than his brother and father, being more akin to his grandfather, the first baronet. In 1911, Sir Percy, who was now living at Hinderton Hall in Neston, oversaw the acquisition of a controlling interest in Brocklebanks, by then the oldest shipping company in Liverpool, and in 1913 the firm merged with the Cunard Shipping Company, a deal successfully engineered by him through his presence on the Cunard board since 1910.

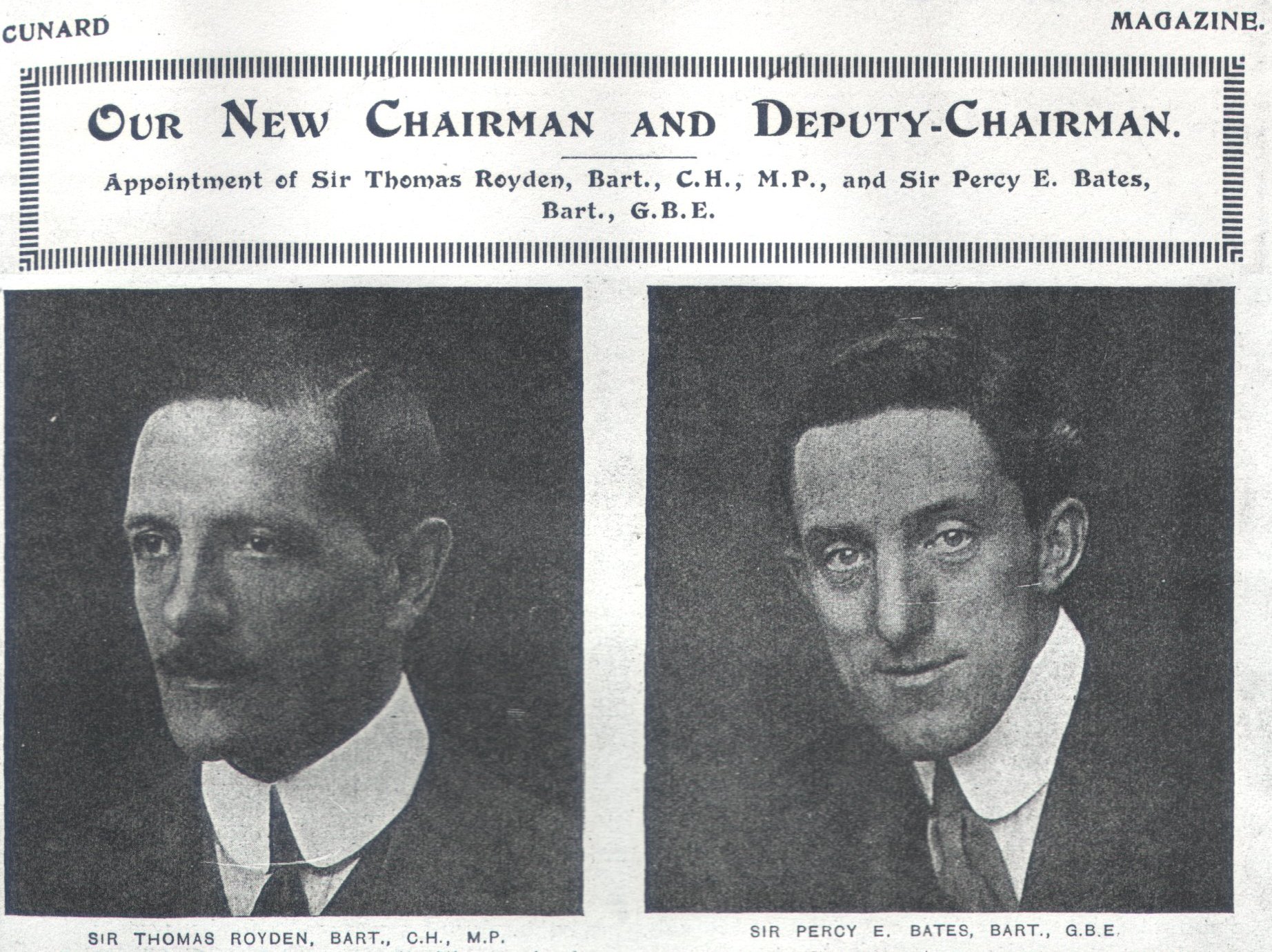

In 1919, Cunard finally acquired a controlling stake in Brocklebanks from the Brocklebank and Bates families, while Sir Percy Bates went on to become deputy chairman of the Cunard Shipping Company in 1922, under the new chairman Sir Thomas Royden, 2nd Bart. [a relative of this author].

Following the retirement of Sir Thomas Royden in 1930 (after he had put plans in place for the construction of the RMS Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth), Sir Percy succeeded him as chairman, and remained so until his death in 1946. His brothers Frederick (1884-1957) and Denis (1886-1959) succeeded him as chairman of Cunard, which thus remained under the family’s control until Denis’ death in 1959.

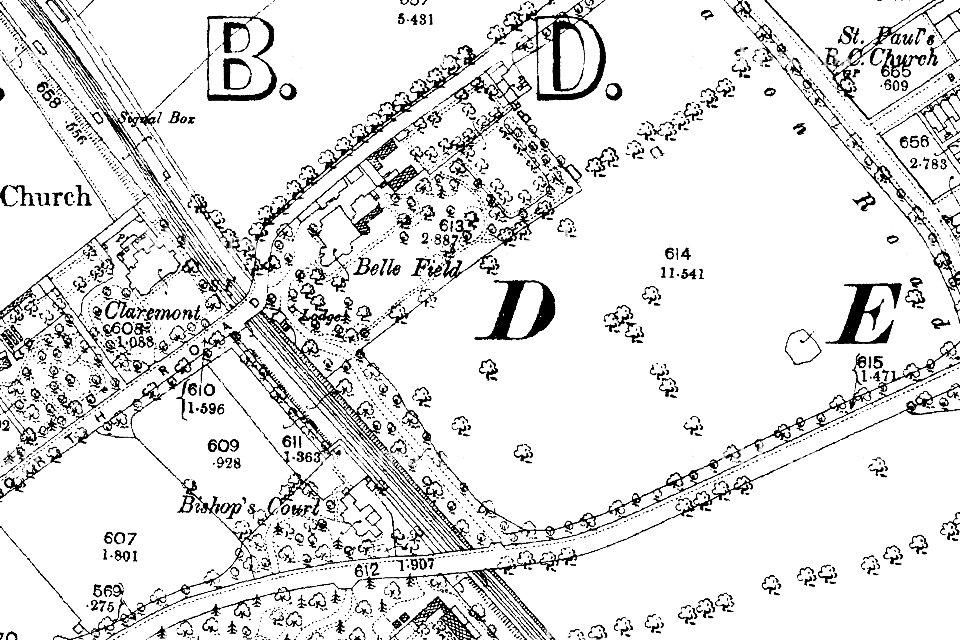

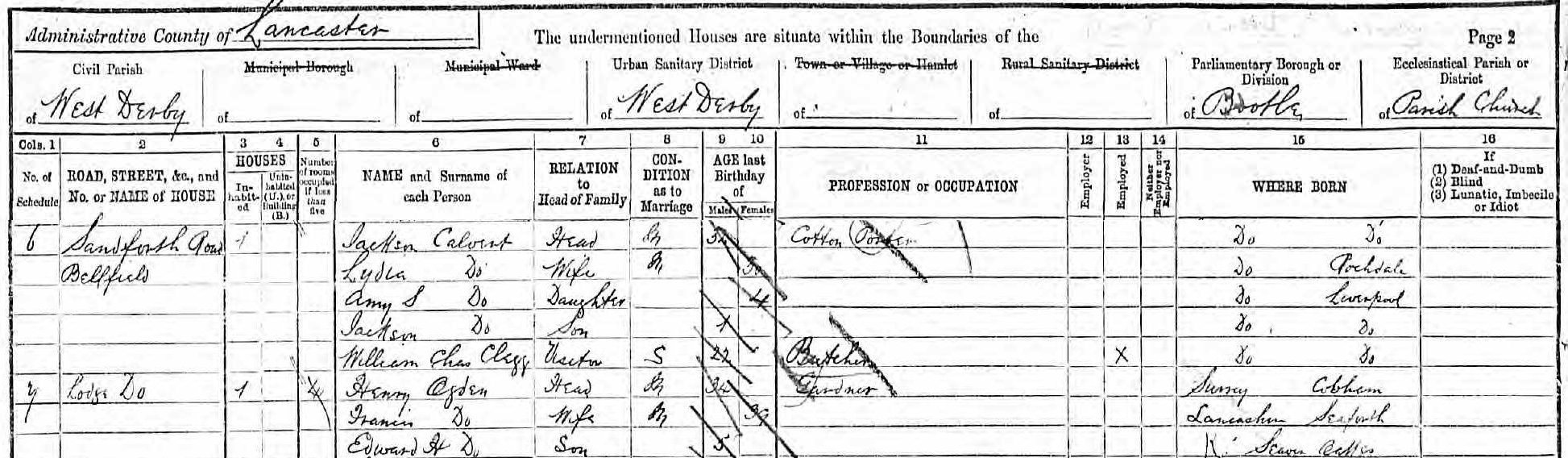

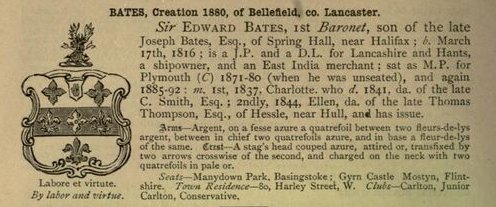

Bellefield, meanwhile, had been mothballed in the 1880s following the family departure, and around 1884 was put in the residential care of a local man, Jackson Calvert with his wife Sarah of nearby Clyde Road. Jackson passed away in 1890, but was succeeded in the position by his son Jackson Calvert junior, who had been working as a cotton porter. The Bates family did not return to Bellefield, while the Calverts remained at the house for a further four decades until 1930.

Local resident John Hoult wrote about the haunting appearance of Bellefield in 1913,

It is an ideal place at which to locate a Christmas ghost story. A long carriage drive, covered with grass and with tall trees arching overhead, leads to the house, which in its ruin is decidedly picturesque. Its many gables, its tall chimneys, its windows each surmounted with dripstone and having leaded lights, and its shield-shaped coat-of-arms over the front door give it an appearance of antiquity, to which however, it is not entitled, the fact that the place has been unoccupied for twenty-seven years, and that the building is not a century old. The sham gothic and the bogus armorials show the place to some advantage in its state of decay; but the interest of the story of every house lies in its inhabitants, and it is especially so in this case. As the old Lancashire proverb has it. ‘There’s nowt so queer as Folk’.

James Hoult, West Derby, Old Swan and Wavertree (1913)

[The house may not have been occupied by its owners, but the Calvert family occupied part of the house until 1930. How accurate the sketch of the coat of arms is above the door we cannot be sure, but the family’s claim to their coat of arms was genuine, ratified by the College of Arms in 1880 on the creation of the baronetage].

……………………………………………………

Inter war period sports ground

In April 1920, at the forty-third ordinary general meeting of the Cunard Steamship Company Limited, held in the Britannia Rooms in the Cunard Building on the Pier Head, outgoing chairman Sir Alfred Booth, Bart, supported by his deputy-chairman Sir Thomas Royden Bart, C.H., and directors, including Sir Percy E. Bates, Bart, reported on the performance of the company in the preceding year, before declaring,

‘You will be interested to hear of another development in connection with our staff. With the return of our men from the Army, the old interest in athletics has been revived and strengthened. Enthusiasm and organising ability were ready to hand, but games cannot be played without playing fields. What was needed was a Cunard sports ground. This we thought it right that the company should supply, and we were fortunate in securing just what we required in the Bellefield Estate, West Derby. Football and hockey have been played there throughout the autumn and winter. An excellent cricket ground, six tennis courts, and a bowling green have been laid out, and we hope that the pavilion, with good changing rooms, will be ready at Whitsuntide, or very soon after. All this is being done at the expense of the company, but the maintenance of the playing fields and the running expenses of the various sports will be at the charge of the athletic club. I hope that some of our Liverpool shareholders will visit the ground some fine Saturday afternoon this summer, when they will see that Cunard men and women can play keenly as well as work well.

Liverpool Daily Post, 29 April 1920

Cunard’s acquisition of Bellefield therefore, dated back to the previous Autumn of 1919. This was clearly of mutual benefit to both parties. Sir Percy was able to dispose of the Bellefield estate that had not been used by the family for many years, while Cunard Line acquired a suitable ground and facilities for the benefit of their employees.

By the start of the 1920/21 season, Cunard were able to enter a team in the newly inaugurated Liverpool Shipping League, playing their home games at their new ground. They won the G.H. Melly Cup in their first season, while arch-rivals White Star Line finished league champions. At the commencement of the cricket season the following year, they fielded an eleven in the local Liverpool league. Other Cunard teams entered local hockey, lawn tennis and bowling leagues. Bellefield was truly underway as a sports ground, which would continue for the next eighty-seven years.

Other sides occasionally played at Bellefield, such as Fairrie & Company (the sugar refiners of Vauxhall Road, Liverpool, before their take-over by Tate & Lyle) but it was a common sight to see Cunard ship’s crews playing against each other in cricket and football, as well as competing within their regular Saturday league teams. But surely the apogee of staff enjoying their leisure time ashore came in 1930. On 11 December, a charity game for the ‘Goodfellow Fund’ took place between the crews of the RMS Scythia and the RMS Duchess of Bedford. The players were due to meet at West Derby Station (Mill Road) at 2pm, (but they had to be quick (and hopefully were already in their kit) as the kick-off at Bellefield was fifteen minutes later!) – and who had the unenviable task of refereeing these seasoned salty dogs? Non other than Dixie Dean! By this time Dean, still aged only twenty-three, was already an England international, the holder of a League Championship medal – and the incredible 60 goal record, so it must have been quite a thrill to be reffed by the Everton star!

Changes were coming to Bellefield however. In 1930, Jackson Calvert, the long-time servant of the Bates family and caretaker of the house and estate, passed away. The house, now uncared for, became a local playground for youngsters and fell into disrepair, then in 1935 it was sold with the entire estate to Tysons, the Liverpool building company. They demolished Bellefield House and built new houses on the perimeter roads, but left the sports facilities enclosed within fully intact. The pitches were in use throughout this period, but Cunard’s association had ended, and the lease was taken up by The Liverpool Cooperative Society, which regularly hosted a variety of sporting events up to the outbreak of war in 1939. The highlight of their year was the well-attended Annual Field Gala on August Bank Holiday, which featured a sports competition, a beauty pageant, flower arranging, music and dancing.

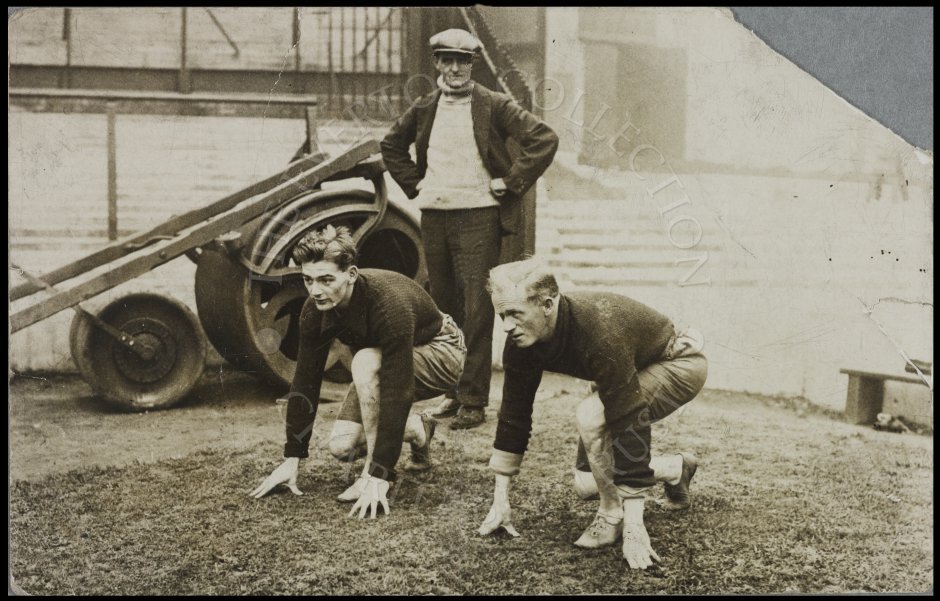

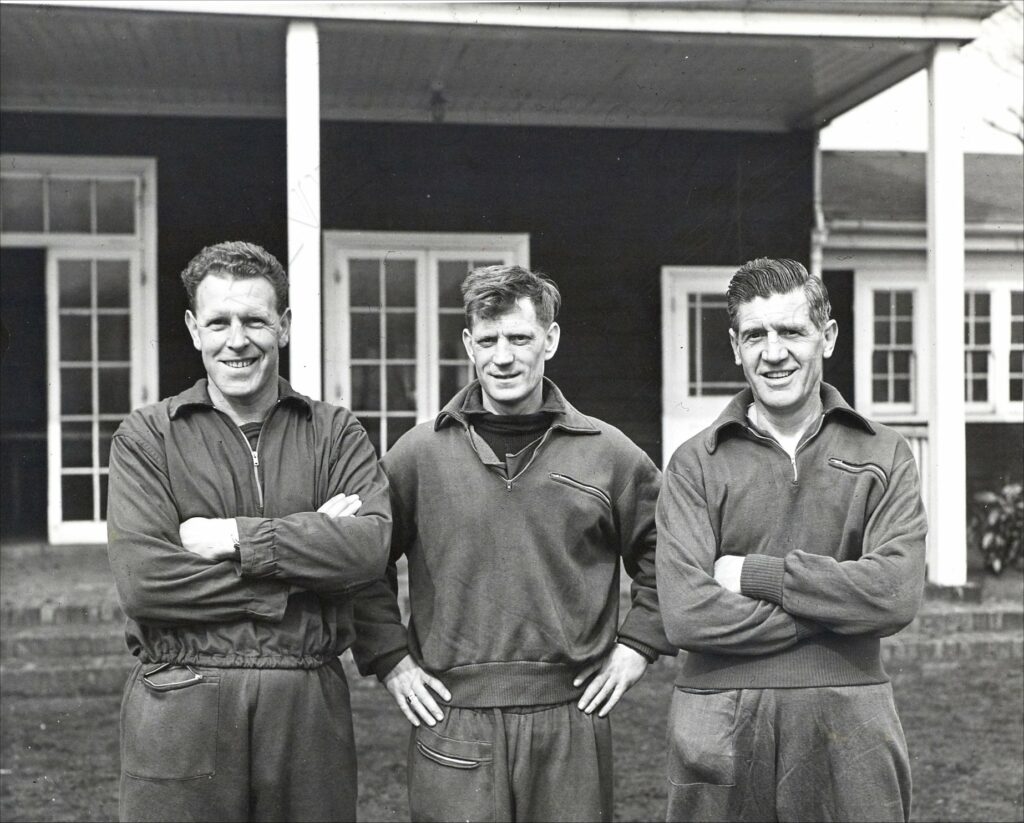

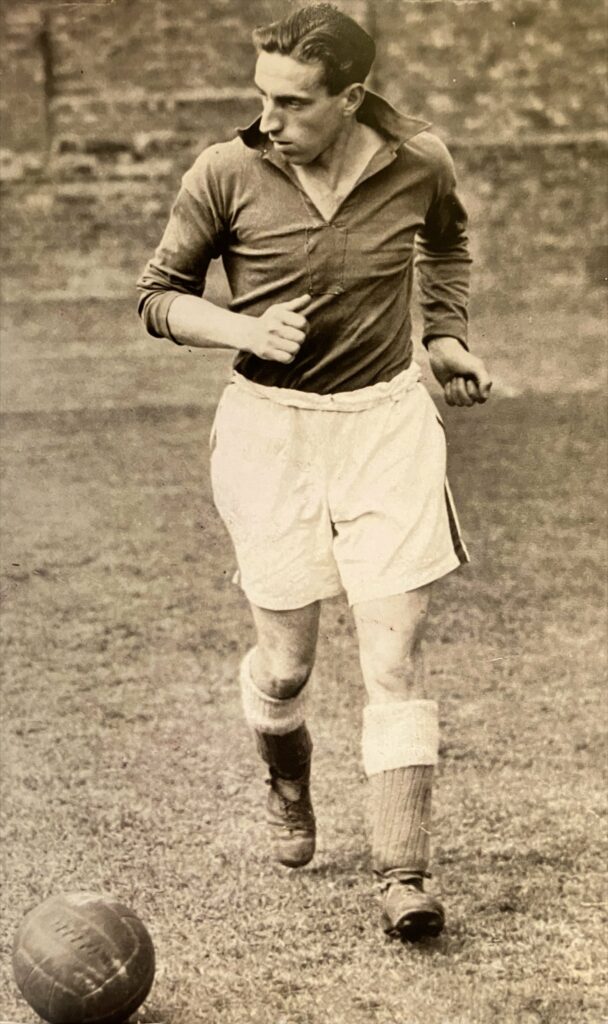

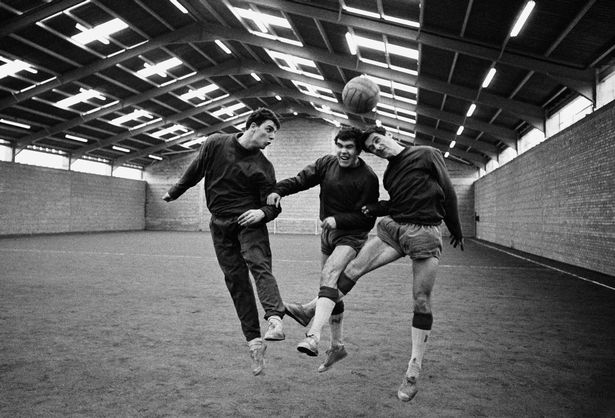

– Harry Cooke with Ted Critchley (and A.N.Other on the right, possibly Archie Clark)

Goodison and Park End Training

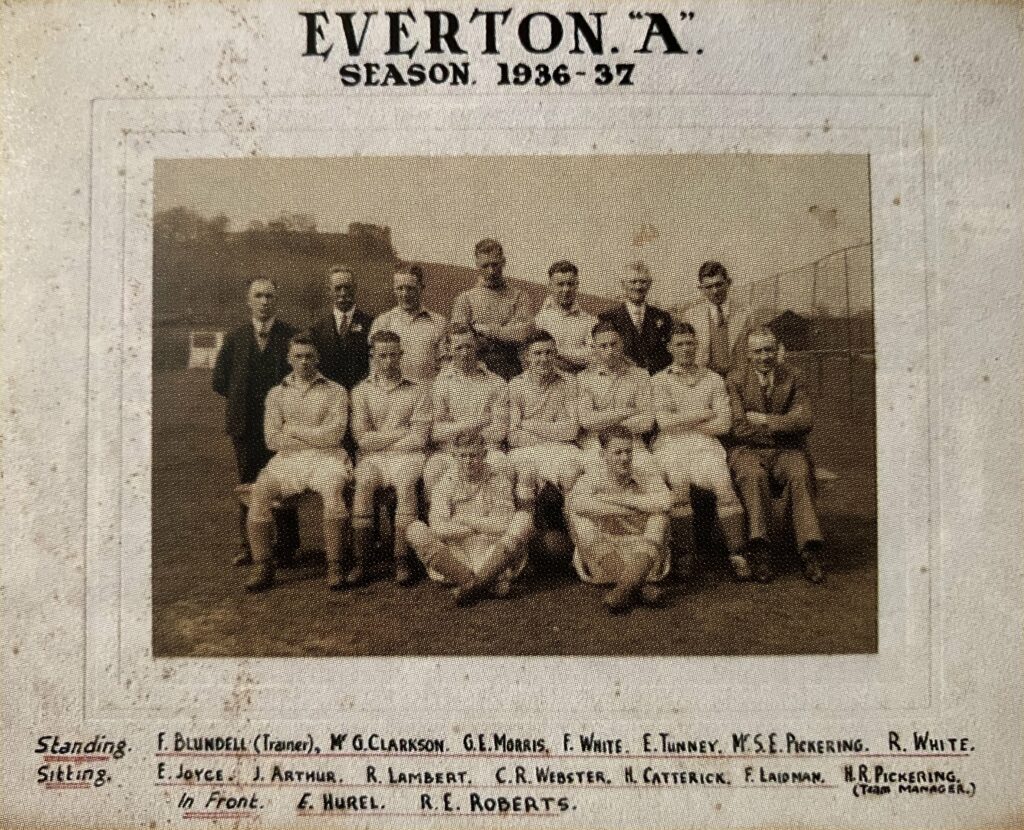

Meanwhile, throughout the inter-war period, the Everton senior players continued to train both at Goodison and the enclosed ground behind the Park End stand, although it was actually the search for suitable facilities for the ‘A’ Team that eventually led to the Club taking on the lease of Bellefield.

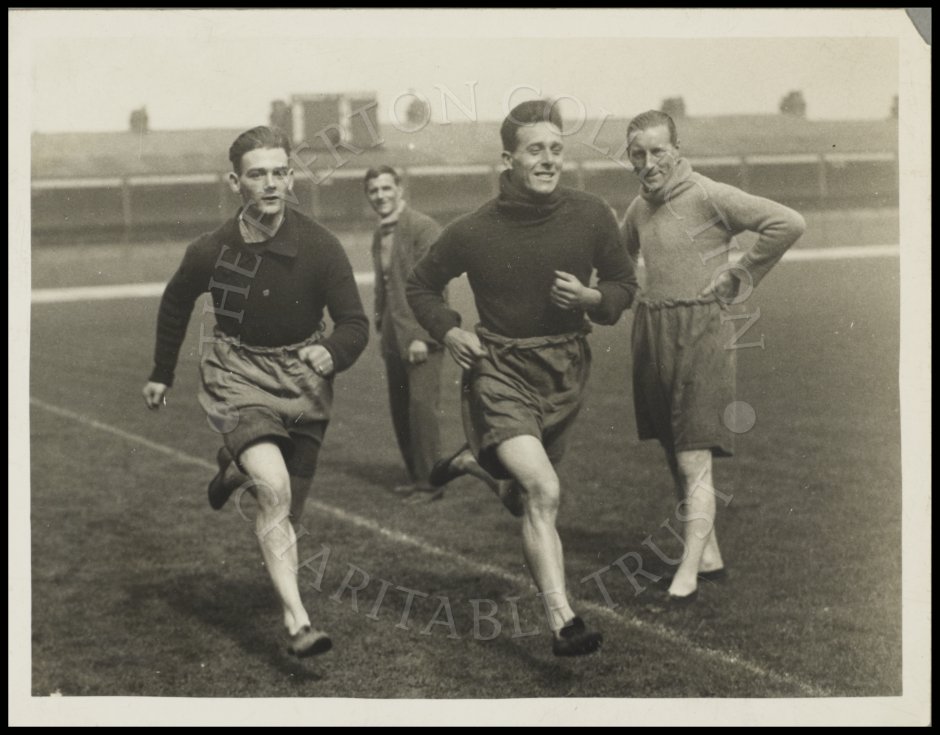

(The Everton Collection)

(The Everton Collection)

Everton FC training at Goodison Park in 1934 – click to view a 2 minute clip

Without a home base following the end of the First World War, the search for suitable facilities for the young players continued until 1922, when the Board reported,

Ground for A Team: It was decided to accept the offer of Mr. Jones for the ground in Townsend Lane, at present occupied by the N. L’pool F.C., for a 2 years lease at £100 a year plus rates, as from 1st September next, and to ask for an option to purchase same at 5/- per yard on expiration of tenancy.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 14 March 1922

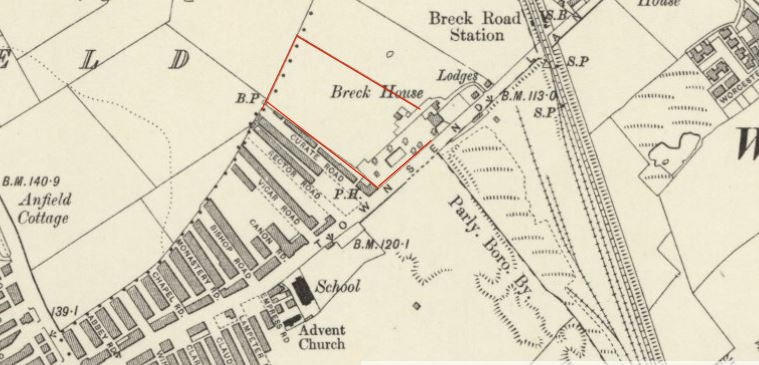

The location was a field directly opposite Edinburgh Park on Townsend Lane, bordered by Curate Road. The entire plot was fenced in and a hut for changing rooms constructed. Other pitches were sub-let by the Board to other local teams such as Anfield Social Club FC when not in use by Everton.

However, despite the investment and plans to acquire a long-term lease, hopes were dashed in late 1925, when it was revealed that the site had been sold to Liverpool Corporation with a view to building housing throughout the area.

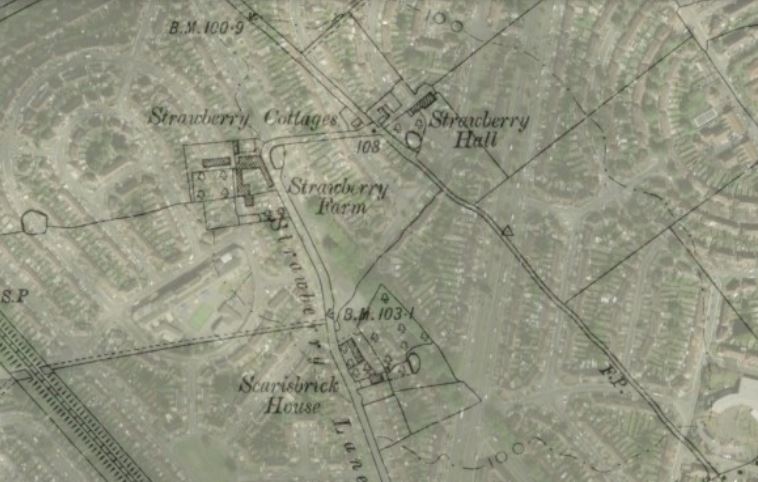

The Corporation offered a pitch in Strawberry Lane/Stopgate Lane, near Strawberry Farm, and after much wrangling, especially concerning the cost of transferring the recently erected fencing and dressing rooms from Townsend Lane, the Board signed the lease. Keen to secure the site on a more permanent basis, the Board tried to purchase the plot in September 1929, but the Corporation again refused, and in June 1930, they took back possession of the plot which fronted the roadside with a view to erecting a ‘Hotel’. This doesn’t seem to have been constructed, as by the mid-1930s the endless spread of the Norris Green housing estates would subsume this site too, and the hunt for facilities continued once more.

On 20 June 1933 it was announced that the Board had agreed to pay Marine FC a rental of £110 per year to lease their facilities for the A Team, an arrangement which was renewed annually until 21 April 1936, when it was recorded,

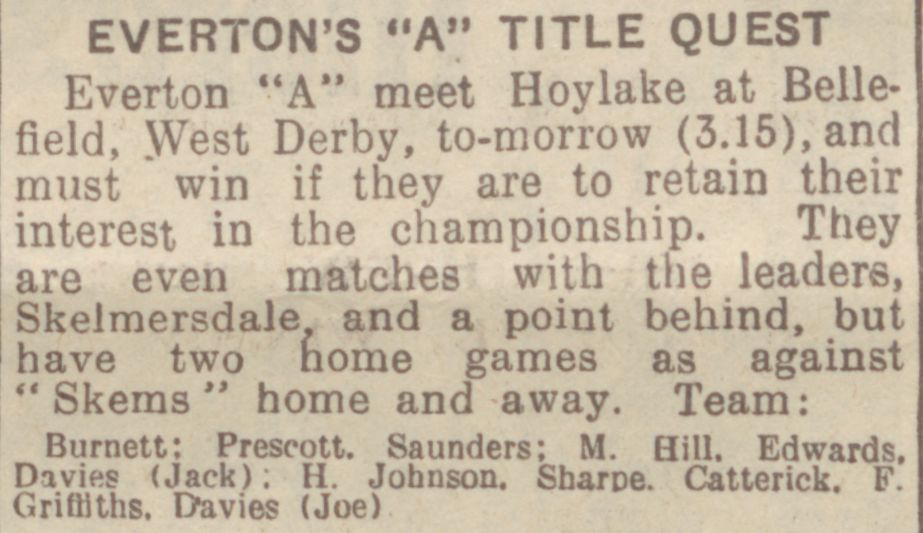

‘A’ Team Ground: It was agreed to terminate the contract with Marine FC and to accept the offer of Liverpool Co-operative Society Ltd for the use of their ground for every Saturday for £75 per annum.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 21st. Apl. 1936

The Co-op ground was, of course, Bellefield, and it marks a significant moment, as although it was a sub-let, this was the commencement of Everton Football Club making use of the Bellefield facilities. It would be the home ground for the ‘A’ and ‘B’ Teams until the outbreak of hostilities curtailed the full football fixture programmes in September 1939.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 21 April 1936 (The Everton Collection)

…………………………………………………

Everton FC tenancy 1946

During wartime, Bellefield was redeployed for the war effort and was used by the National Fire Service as one of its main North Western Depots, and later, in the early days of the gradual post-war handover, it was a common sight to see fire engines parked in the driveway. On the sporting front, Bellefield continued in use throughout the Second World War. However, the professional Football League fixture list was suspended, and under wartime restrictions it was instead focused on localised competition. Consequently, the A & B teams returned to Everton playing only occasionally. Meanwhile, Bellefield became the home base of two local Liverpool County Combination sides, St Teresa’s and Carlton, both playing regularly there throughout the war years, including fixtures against Everton A and Liverpool A in the same league.

However, as the war drew to a close, a major development was afoot, as the Minutes of the Board of Everton Football Club reveals,

Junior Grounds: The possibility of acquiring Bellefield, Sandforth Road, with its accommodation for 4 teams, was considered, and agreed that this was highly desirable. The rent plus rates would amount to £350 annually. Secretary instructed to make enquiries with a view to a long lease being obtained.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 22 March 1945

The acquisition of such a lease would give Everton full control of the facilities, and enable the club to develop the site as they saw fit – as well as controlling all access and use.

The following month it was minuted,

Bellefield: It was noted that the W. E. Tyson Estate Co. were prepared to enter a tenancy agreement in our favour, for a period of 21 years on an annual rental of £250., tenant paying rates.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 18 April 1945

Negotiations between the club and Tysons progressed favourably, and by the summer,

Bellefield Sports Ground: Secretary reported the expectancy of early occupation of this estate, and was instructed to expedite the drawing up of tenure agreement with Messrs Tyson’s Estates Ltd.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 17 August 1945 (The Everton Collection)

However, progress in drawing up the final documentation dragged on to early the following year,

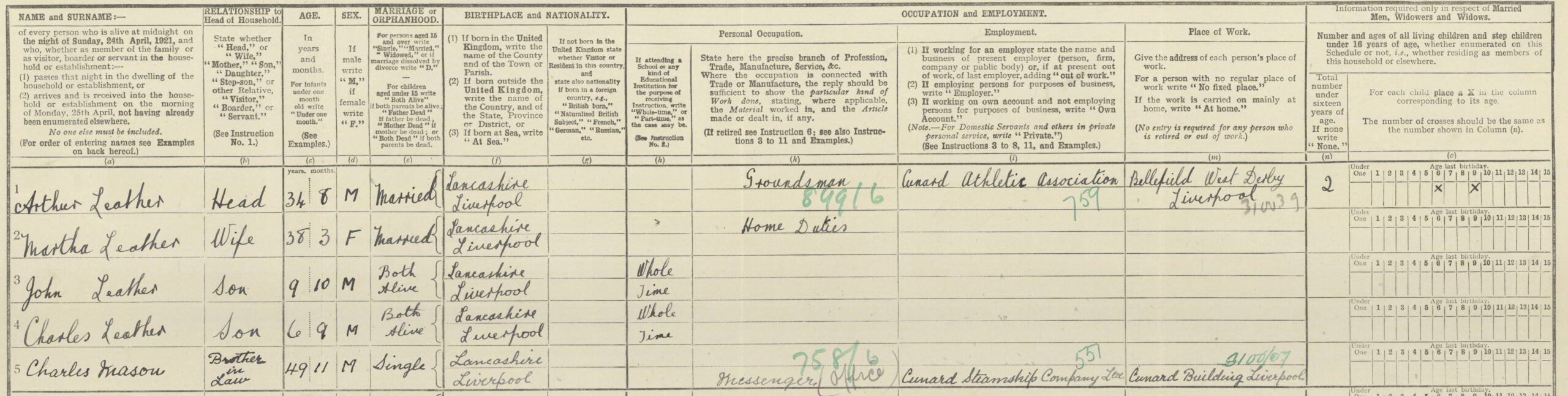

Bellefield Sports Ground: Copies of the suggested terms of the 21 years lease were considered, and the trend of our ideas to be conveyed to Mr. J. C. Bryson, acting on our behalf, – were given to the Secretary. The latter was empowered to deal with Mr. Arthur Leather, the resident groundsman, to obtain his services as soon as possible, at a reasonable figure of wages, having in mind his occupancy of the cottage at the entrance.

Arthur Leather: It was agreed to offer this man £3/10/- per week & tenancy of his cottage & rent free, to become groundsman of the Bellefield estate, from the date we take over the lease, & in line with the date he would be free to undertake the duties involved.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 14 Feb 1946 (The Everton Collection)

The sale went through shortly afterwards, and Arthur Leather, who had been employed by Cunard as groundsman since their purchase of Bellefield in 1921, was confirmed to carry on in the post in February 1946, as well as his continued occupancy of Bellefield Cottage, his home since his original appointment.

After the war years, this felt like a fresh start for the club, to able to utilise such fine new facilities, and to take the pressure off the constant reliance on Goodison, allowing the turf time to recover. This did not end the use of Goodison and the Park End practice ground for training, but this was much reduced, with players now being taken to Bellefield two days a week by bus after reporting for duty at Goodison each morning. As before the war, it was also the home base for the youth set up, where the club now ran A, B, and C teams in local leagues. As well as these pre-war links, the lease also came about, no doubt, through links already forged with Tysons, who were in contract with Leitch, still busy overseeing repair work to the Goodison infrastructure.

Another club side to use Bellefield in those early years was the Everton Baseball team, which had played regularly at Goodison since the thirties – and to where they initially returned to after the war;

Baseball: It was agreed that as previous experience had proved this game to be not detrimental to our ground, permission be given for use for 1946 season. The Chairman drew attention to the fact that our players were interested, and that the trainer considered it to be good summer training.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 14 Feb 1946 (The Everton Collection)

Back row: A.Robertson senior, W. Borthwick, D.E. Falder, T. Gordon Watson, G.G. Burnett, A.Robertson. Front row seated: G. Robertson, T. Gardner, J.A. Jones, T.C. Potter, Mr H. Pickering (Team Manager)

There was a smattering of interest in the sport following a few exhibition games at Goodison, but it was only after John Moores, a keen fan of baseball, encouraged local teams to form and join a Liverpool league in 1933 that it really took off in the area. Football coaches saw it as another way to boost fitness levels and improve team spirit, while Theo Kelly, Everton’s Secretary in the 1930s and 1940s, was also an advocate, and was instrumental in Everton fielding their own team. In fact, there was so much support from baseball leagues across the country, that Moores played a key role in the establishment of the National Baseball Association.

However, this was to be short lived. the Board, now keen to restrict the use of the pitch at Goodison, voted to curtail the hosting of baseball games in 1948, especially as there was now a viable alternative,

Baseball: It was agreed that no further baseball games should take place at Goodison Park. It was further agreed that the Everton F.C. team should play their games at Bellefield, and that other applications for the use of Bellefield, be considered on their merits, by the Sub-Committee.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 6 August 1948 (The Everton Collection)

But when Cliff Britton took over Everton FC team affairs from Theo Kelly in 1948, he quickly ended the players’ involvement in the sport,

Baseball: Application was read from Robins for use of Bellefield. The application was approved on the basis of £1 per match, with a minimum of £10 per season of 1949. Other applications to be dealt with pro rata. Mr. Britton was asked for his general opinion with regard to our players, and he did not wish that our professionals should be included in our representative team.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 15 September 1949 (The Everton Collection)

The final death knell came the following year, agreed by the Board at the same meeting when the future of Bellefield was secured, following the extension of the lease for a futher two decades;

Baseball: Agreed that no further baseball be played at Bellefield.

Bellefield: Agreed that an extended lease to February 1st, 1988, be taken out at a rental of £325 per annum.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 15 September 1949 (The Everton Collection)

……………………………………………………

Training at Goodison Park

(The Everton Collection)

The Park End/Bullens Road training gound can be clearly seen in the centre foreground

……………………………………………………

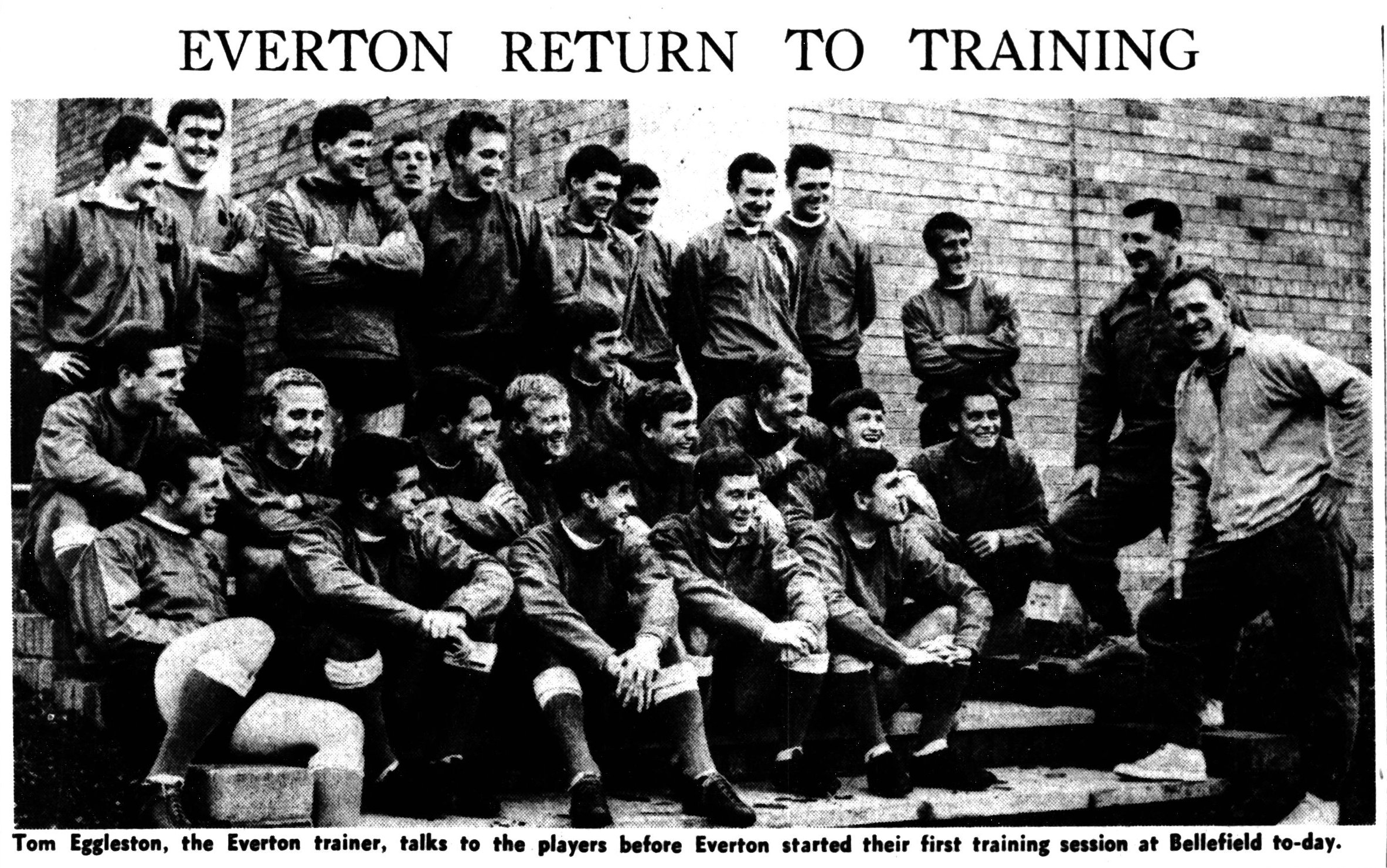

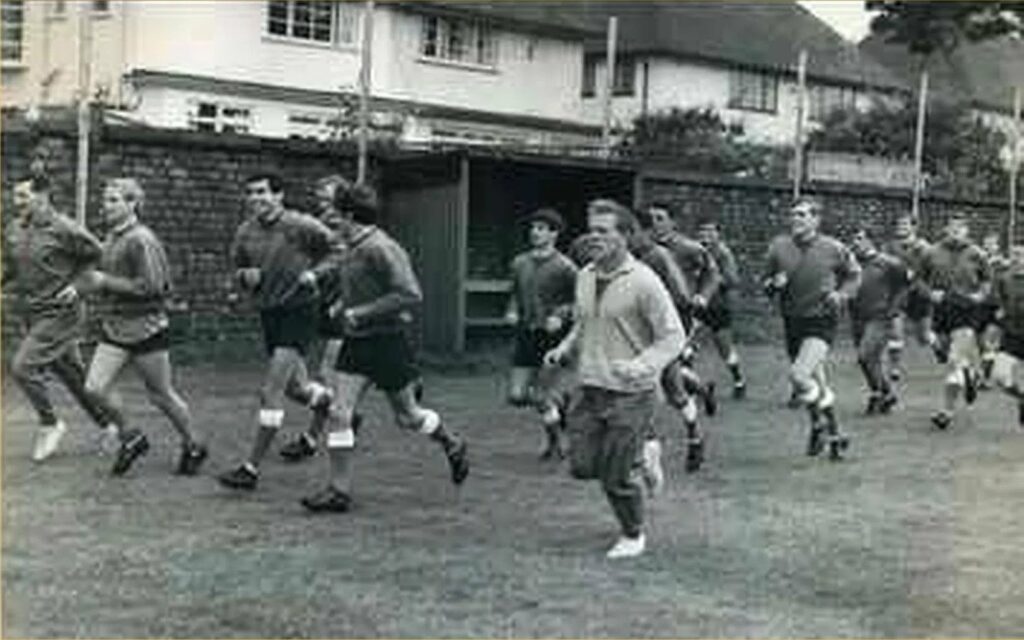

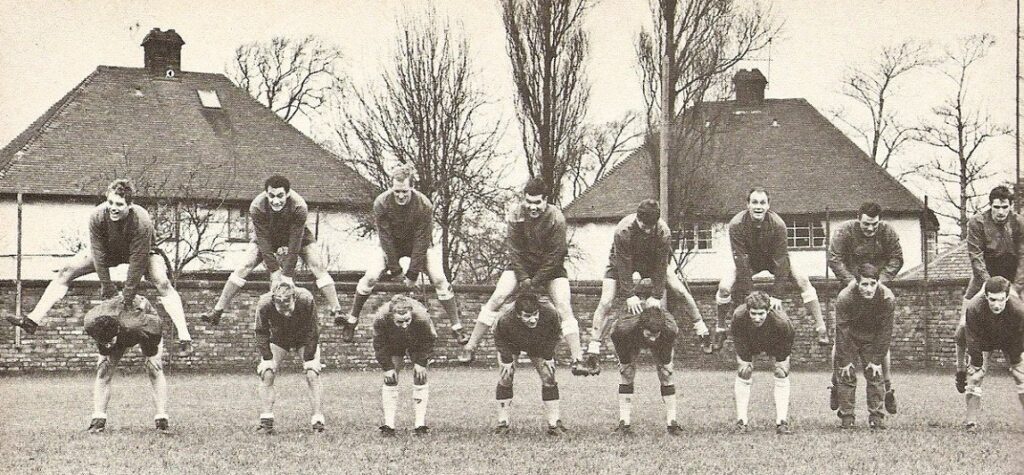

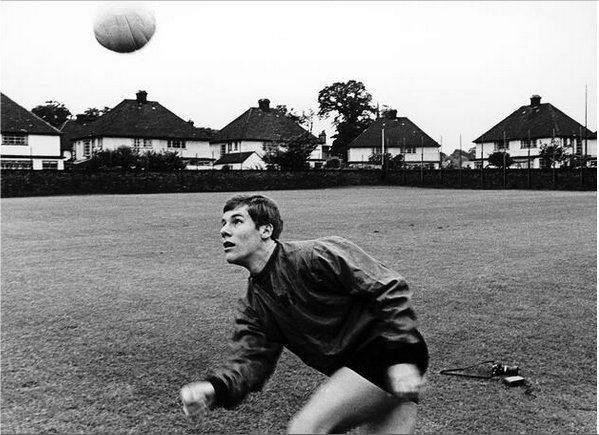

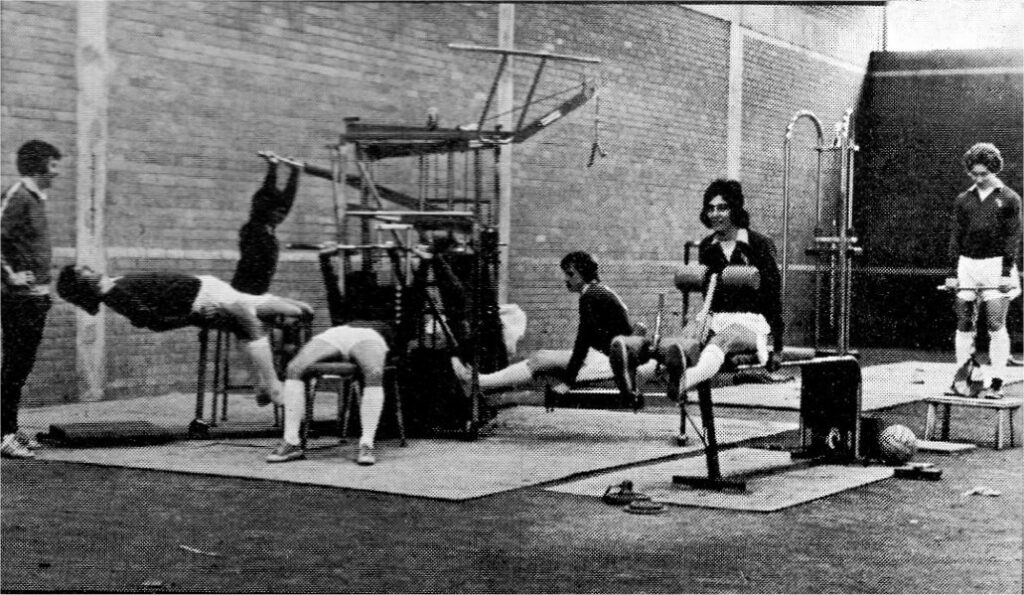

Early photographs of Training at Bellefield

(The Everton Collection)

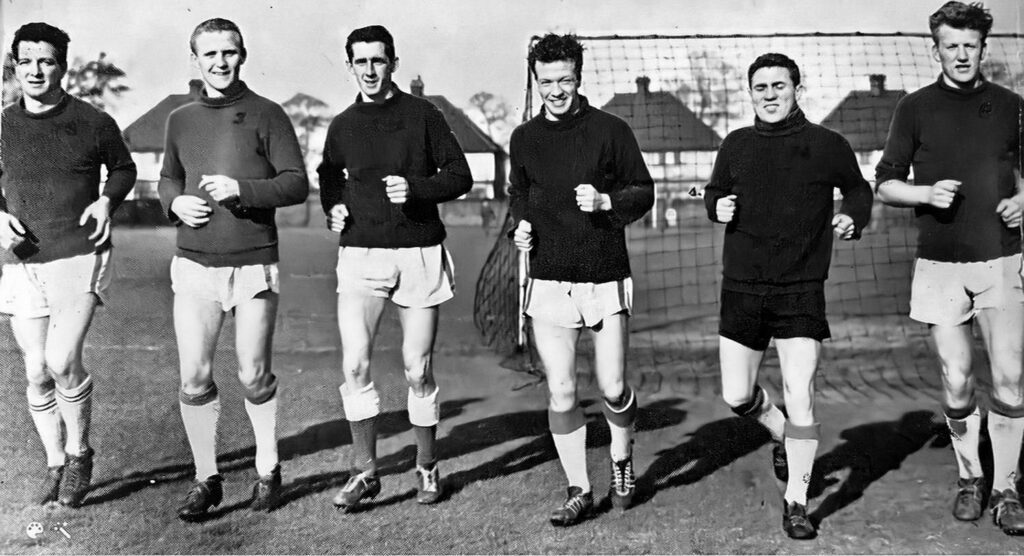

Pictured in their change strip in front of the old Cunard pavilion at Bellefield

Liverpool Echo, 3 February 1948

Liverpool Echo, 3 February 1948

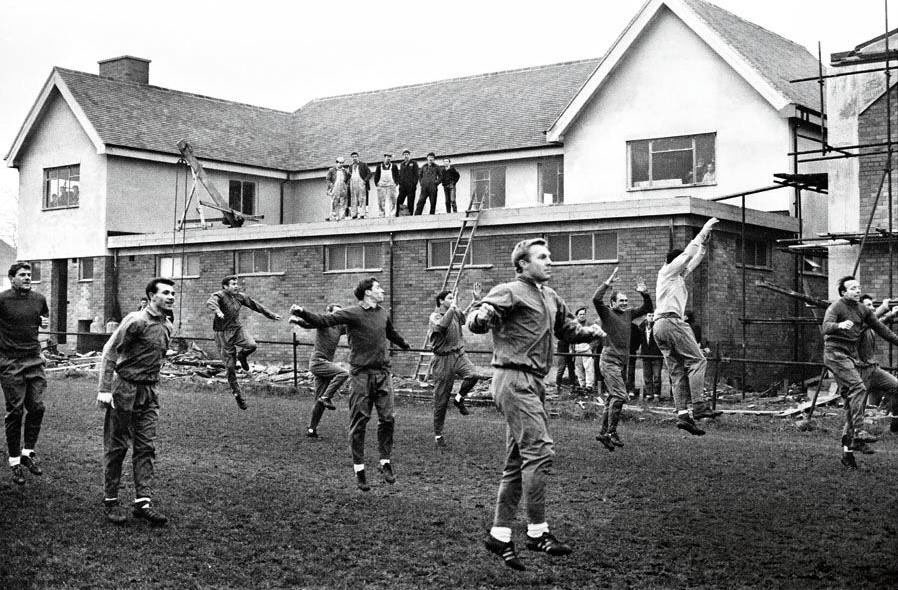

The recent housing, constructed by Everton’s landlords Tysons, at the rear.

(The Everton Collection)

Training had started to develop a bit by the time I’d returned from National Service in Egypt, and Britton had become manager. Typically, we’d do a warm up, then laps of the pitch, and sometimes we’d go to Goodison and run up and down the terraces. Then came some really hard physical work, before having a game of five-a-side. We’d play different types of that game; one-touch, two-touch. Increasingly, there was talk of tactics and game plans. The perception is that players back then weren’t really into those sort of things, but we certainly realised how important it could be on match days. – Dave Hickson

from James Corbett & Dave Hickson, The Cannonball Kid (2014), p.41

(The Everton Collection)

From the commencement of the lease in 1946, it was clear that the off-pitch facilities were in need of an upgrade to meet the demands of a top flight First Division club. Consequently, even when the players trained there on the regular Tuesday and Thursday rota, after they had reported for duty at Goodison before 10am, the bus took them back to Goodison to shower and have lunch, before being transported back to Bellefield for the afternoon training session. Yet, this arrangement continued throughout the fifties and into the early sixties.

It is hardly surprising that all the training became the domain of the first team coaches, while the manager focused on the day-to-day running of the club, with occasional forays onto the training pitch – and even that would be in a hat and coat.

In his study of Cliff Britton and his early venture into management at Everton, Rob Sawyer featured the thoughts of some of those players who were there;

Jimmy Harris recalled how Cliff was seen from a young player’s perspective: ‘He had an aura about him, nobody argued with him. He was very strict and kept the directors in their place. On a Friday morning we’d be lapping the track around the pitch at a very leisurely pace. Then you’d see the trilby come up through the entrance to the directors box in the main stand and he’d be watching you – the pace soon picked up!’

Mick Meagan recounted, ‘Cliff was really strict but also a very nice man, a man to respect. Under Cliff we’d be enjoying training, playing 5-a-side and then he would arrive in his Crombie coat and trilby and stand there, then the fun factor would stop! There were no tracksuit managers in those days. Cliff left the training to Stan Bentham and Gordon Watson – he trusted the staff and that was it. Managers back then always reminded me of race horse trainers coming to see how their horses were looking at the gallops.’

Derek Temple, then a teenager in the reserves, remembers seeing the manager at a distance: ‘On Tuesday and Thursday nights the lads who weren’t full time professionals trained in the concourse under the Gwladys Street stand, with balls hung up under the girders. We used to run round and jump to head them. At one end there were nets and had goes at shooting. With all the dust you wouldn’t notice Cliff Britton come in, but then, in the shadows, sometimes you’d suddenly see this figure in a big overcoat and trilby hat watching, and it would be, “Oh, eh-up here’s the boss!” ‘ (6)

……………………………………………………

In February 1956, Cliff Britton departed Everton in acrimonious circumstances, following which, the Board made an unusual decision to replace him with Ian Buchan, a sporting fitness guru from the University of Loughborough, with no professional football experience as a player or manager. The local press were particularly keen to see how he would implement his new approaches to training;

Everton Players Are Enjoying New Style Training

Ranger’s Notes

Everton F.C players have now been in training for the forthcoming football season for ten days, and with the idea of seeing how they reacted to the new regime at Goodison Park I spent some time there at the weekend, watching them at work and chatting with Mr. Ian Buchan, the club’s physical training expert.

Hard training is no joke in the humid weather we had most of last week, but the very sensible ideas which Ian Buchan is bringing into operation seem to have taken the drudgery and monotony out of the job, and I found the players in excellent spirits.

The first few days, one of the lads told me, were pretty tough, but they are now feeling the benefit and their fitness is such that they can now tackle things that at one time would have been beyond them. Peter Farrell for instance, informed me that on the previous day, he had done 20 quarter-mile laps at Bellefield without a stop.

“If anybody had told me 10 days ago I would do that I wouldn’t have believed them.” He added, “Our coach knows his stuff all right and everybody, is getting much more enjoyment out of the pre-season preparation than we thought possible. To be candid, I never imagined I should relish training as much as I have this last week or so. It has been quite an eye-opener.”

Tommy Eglington, Jimmy O’Neill, and several other players said much the same thing when I spoke to them during a lull in their schedule. Even Gordon Watson and Stan Bentham, who have been going through a somewhat similar experience, spoke of the benefits they had derived.

Though everybody agreed that it was a bit severe at first, they have now settled down to a steady routine, which is being gradually increased in its scope, to achieve still greater benefit. Mr. Buchan told me of his pleasure at the attitude of the players and their keenness to co-operate in every possible way. “They are determined to achieve the peak of condition and equally resolved to do well on the field of play which is the vital thing,” he said.

The Basic Idea

“The purpose of the initial training of the past 10 days has been to achieve basic fitness,” he added. “That is the solid foundation on which I hope to build their speed. Later on we shall go into other matters, such as the tactics to be employed the varying strategies during individual games, and so on.”

I gathered that in many respects the training which the players are now undergoing is entirely new to them. At the same time, the Buchan system lays on claim to providing a royal road to quick success on the field of play. I could not have agreed with him more than when he remarked that success comes only after a lot of hard work, then still more hard work, together with constant and repeated practice in all the finer arts of the game.

I have preached that gospel long enough. He summed it up with the remark that soccer success is made up of 90 per cent perspiration and 10 per inspiration. His aim so far has been to make the players interested in training by providing an infinite variety of tasks for them to tackle. They never keep on at one thing long enough to get browned off with it.

Geared to Individuals

At the same time everything is related to the basic principle of playing football. The emphasis is always on that fact. The principles of soccer are embodied in many other games which are now being introduced into the daily schedule to kill any semblance of monotony.

If the cheering of the players when I watched them is anything to go by that is being achieved. One point which Mr. Buchan stressed is that the training is geared to the capacity of each individual. Obviously what one can do may be quite beyond the capacity of another. Each player will be expected only to reach his own maximum potential in various directions. He will not be asked to attempt things beyond his ability merely because somebody else can do them. “We are aiming at a happy and sound team spirit,” he went on, “and I am sure we shall, achieve it.

The players are co-operating wonderfully well, and realize that not only myself, but everybody connected with the club is anxious for their well-being and future success. Mr. Harold Pickering, the club’s administrating officer who is working in close co-operation with his new colleague, told me that he had never known, in his association with Everton, such an air of optimism and confidence as permeated the dressing room at the present time.

“There has been no shirking” he said. “Everyone has worked with a smile and there has been a splendid atmosphere right from the moment the players reported back.”

Mr. Pickering is in the middle of going through the long list of amateur players who are having evening trials at Bellefield. Sixty were put through their paces last week and there are as many more waiting for games during the next fortnight or so.

Recently he has been so “thronged,” as they say in the mill towns, that he has not been able to fix up his holidays, and with the season almost on top of us, it seemed he may have to forego them this summer. That, however, won’t worry him unduly, so long as Everton are ready to meet the new campaign with everything in apple-pie order and every step taken to ensure as far as possible, that the future is going to realize the hopes and expectations of those connected with the club.

Ian Buchan has also sacrificed his holidays. He took over at Goodison Park three days after finishing at Loughborough College. In his own words, he is enjoying the work here so much that it is as good as a holiday.

Liverpool Echo, 30 July 1956 (7)

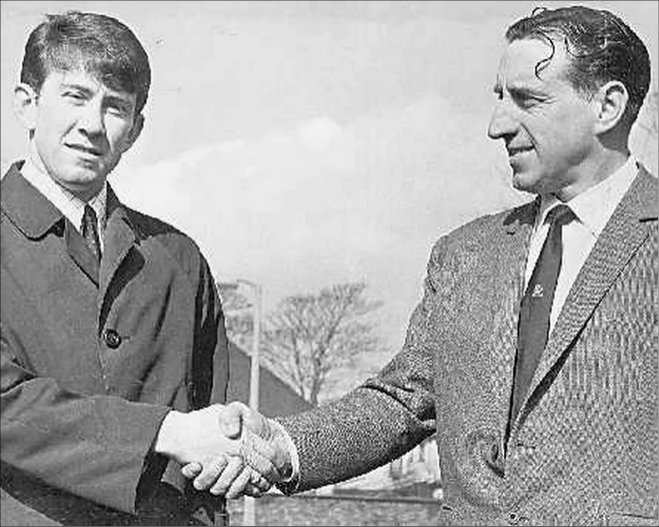

The attempted forward thinking experiment with Ian Buchan came to an end just two seasons later, when he was replaced by Johnny Carey, which proved to be another fruitless appointment. The real sea change was to come with the election of John Moores as chairman of the club in June 1960, and the arrival of former Everton forward Harry Catterick as manager in 1961.

Redevelopment of the tired training facilities at Bellefield would be high on Catterick’s agenda, and Moores was just the man to see it implemented.

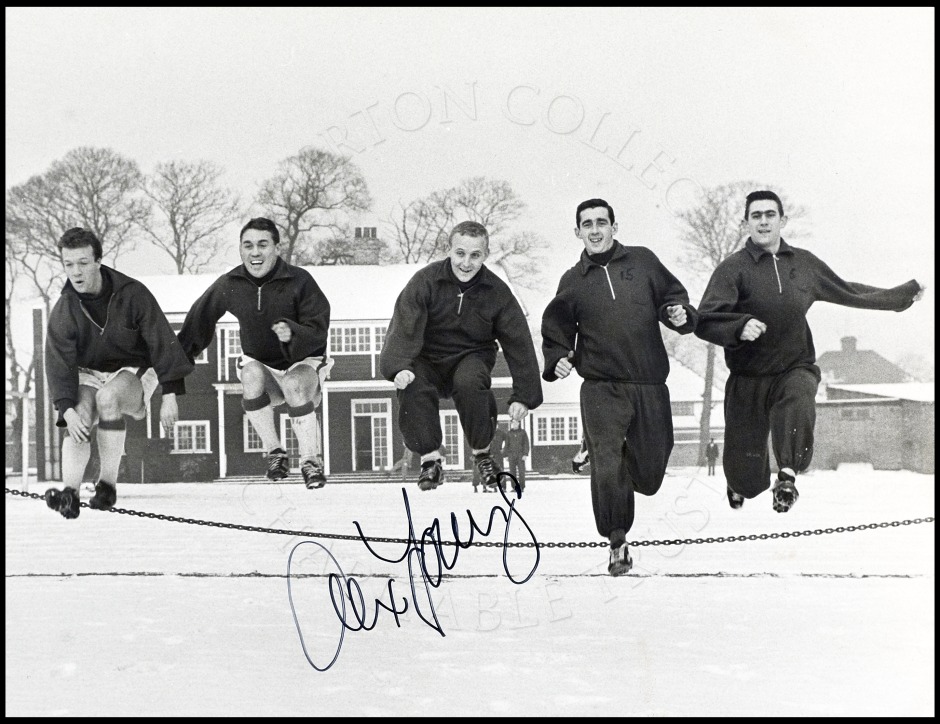

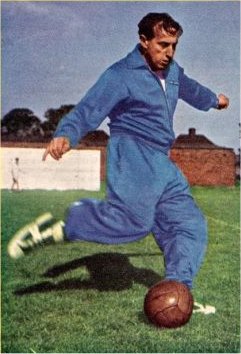

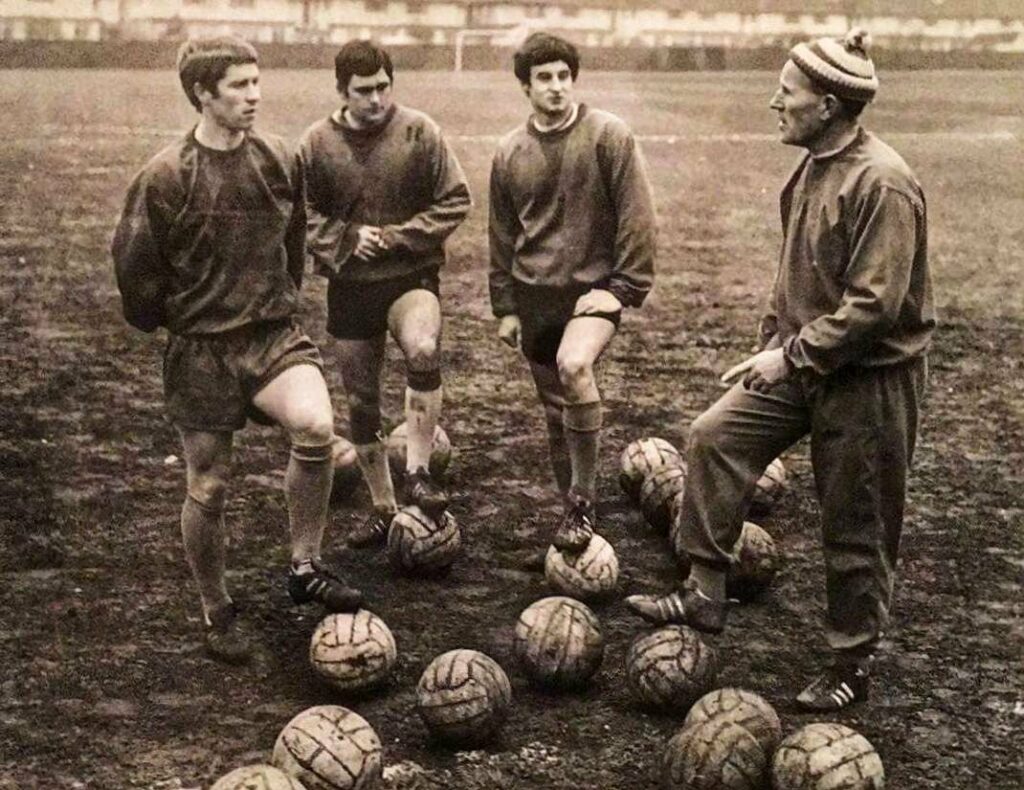

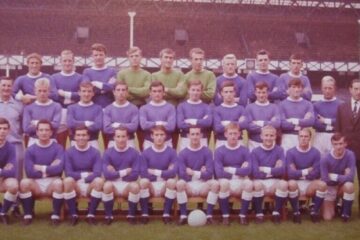

Alex Parker, Alex Young, Roy Vernon, Billy Bingham, Bobby Collins, Jimmy Gabriel

Despite the new training methods introduced in the late fifties, the arrangement of using the split sites of Goodison and Bellefield was clearly inefficient, and wasted valuable time which could be better spent on one enclosed complex.

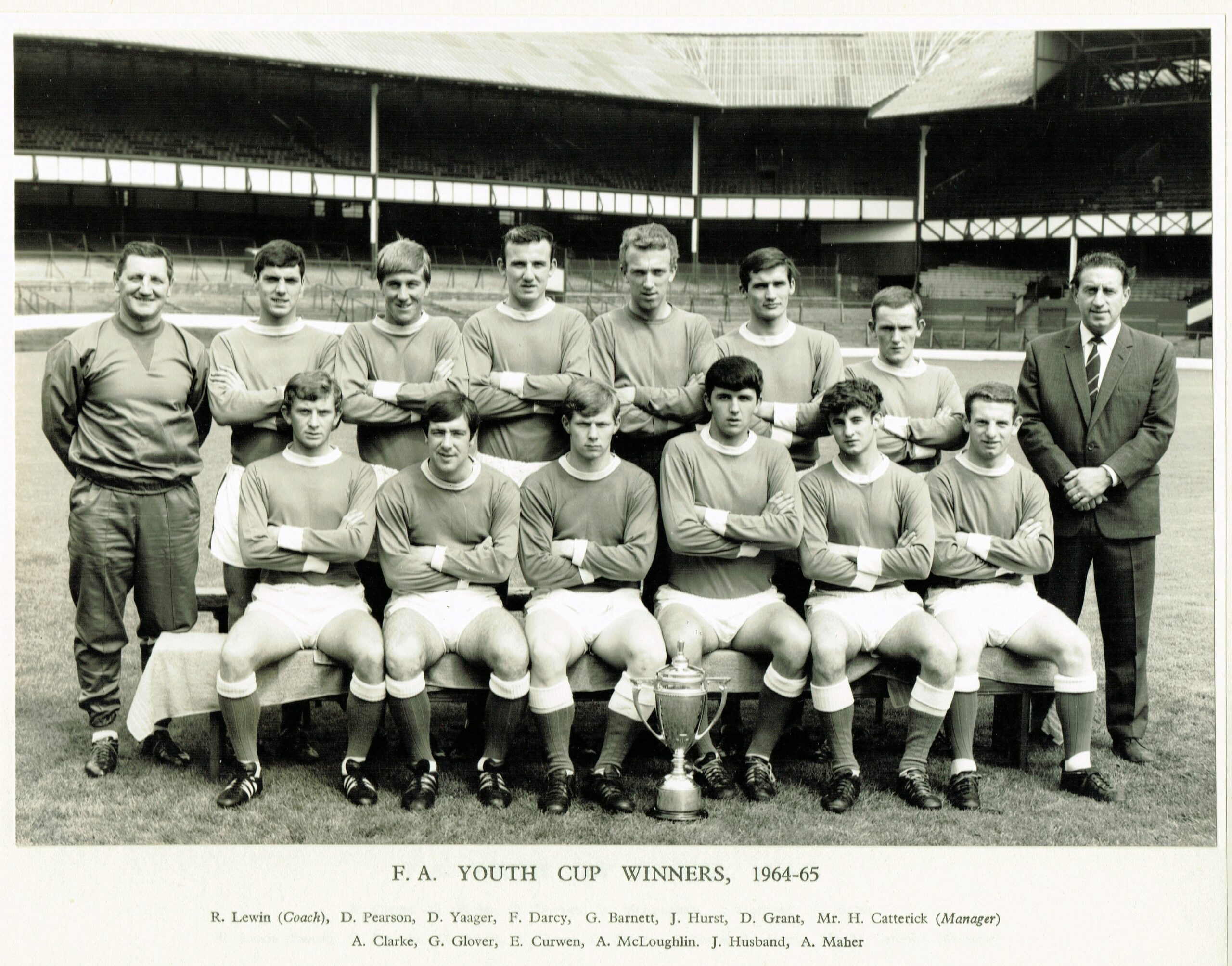

Catterick spoke about his vision to Colin Wood of the Daily Mail a few years later,

‘When I came here, I thought we could do more in the way of developing youngsters. It paid off last season (1964/65) with the Youth Cup. Now we have a period when these players have to reach senior status. Some may fall by the wayside, others may come through, but this is a natural process.’ (quoted in Rob Sawyer, Harry Catterick (2015), p.113).

Bellefield was there when I was a youngster as a sports ground with a wooden tennis hut, but the pitches were not good. We’d made a fair amount of money and John Moores said, ‘What do you think we can do about this?’

So I replied that I’d like to see a football factory – self-contained where people can report, bathe, eat, train and have treatment. Where, once they are in, there is no need to come out until they have finished their training. He asked if I had any ideas, so I made a few rough sketches and discussed it with an architect associate at their organisation; it evolved that way.’ (8)

………………………………………………..

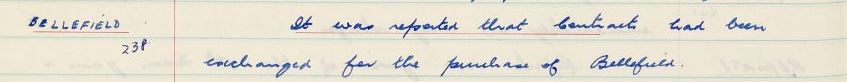

The Purchase of Bellefield – 1962

In 1962, while only thirteen years into a 20 year lease of Bellefield, owners Tysons approached the Everton Board with an offer for the club to purchase outright;

Bellefield: It was reported that Tysons were prepared to consider selling Bellefield and whilst the valuation was £15,000.0.0, it was anticipated that a figure in the region of £25,000.0.0 would be asked. It was agreed to negotiate to purchase at the best price possible. Everton FC Board Minutes, 17 July 1962 (The Everton Collection)

Everton director Mr E. Holland Hughes was tasked with negotiating the purchase, which rumbled on until November later that year, when it was completed for £25,000 and contracts exchanged. Within weeks the redevelopment of Bellefield was underway, initially carrying out sweeping renovation work, then by 1964 plans for a new pavilion were approved and construction was commenced.

Everton FC Board Minutes, 12 November 1962 (The Everton Collection)

However, as the redevelopment was well underway to make both Goodison and Bellefield the envy of every other club in country, the club was rocked at the Annual General Meeting of the Everton Board on 29 July 1965. The chairman, ‘Mr Everton’ – John Moores – who’s investment had made many of the changes possible, and had turned the club’s fortunes around, announced his resignation to a startled audience. His five-year tenure at the helm since July 1960 had so far realised his dream of bringing success back to the club he loved with a passion – and in an attempt to recreate those halcyon days of the thirties he witnessed as a fan in his youth.

However, he quickly reassured everyone as to his continued commitment to Everton, as he intended to stay on as director, but the demands of his business interest in Littlewoods, which would entail foreign travel and prevent regular attendance at Board meetings, convinced him it was the right decision to stand down. His place would be taken by Mr E. Holland Hughes.

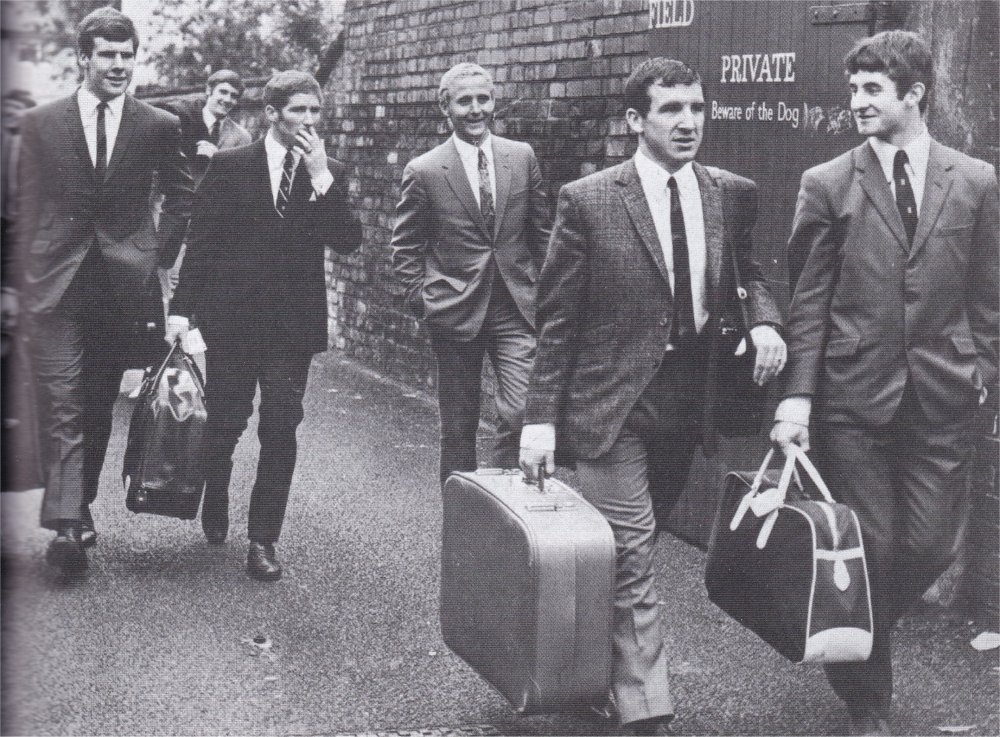

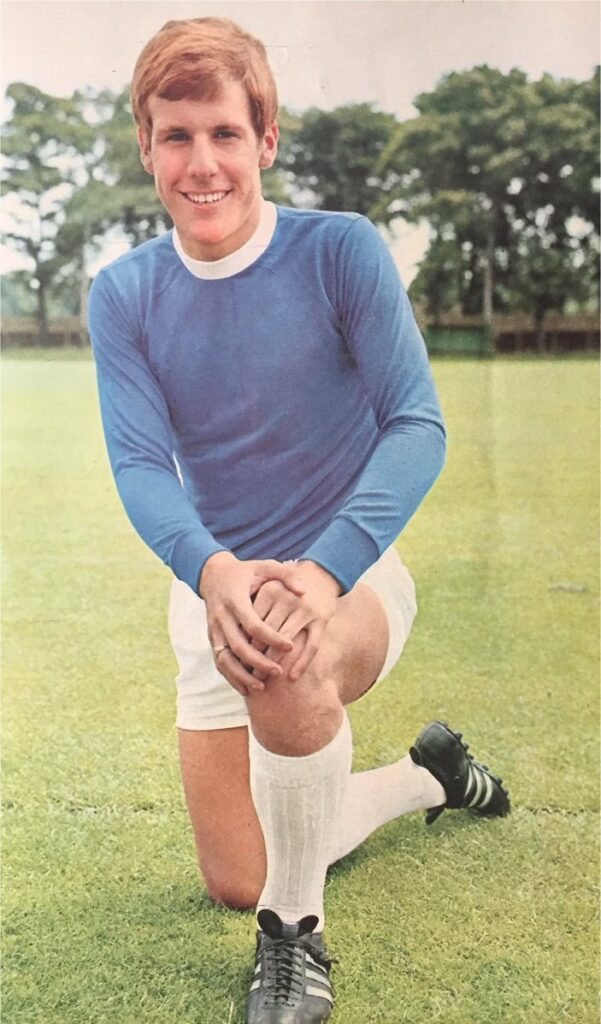

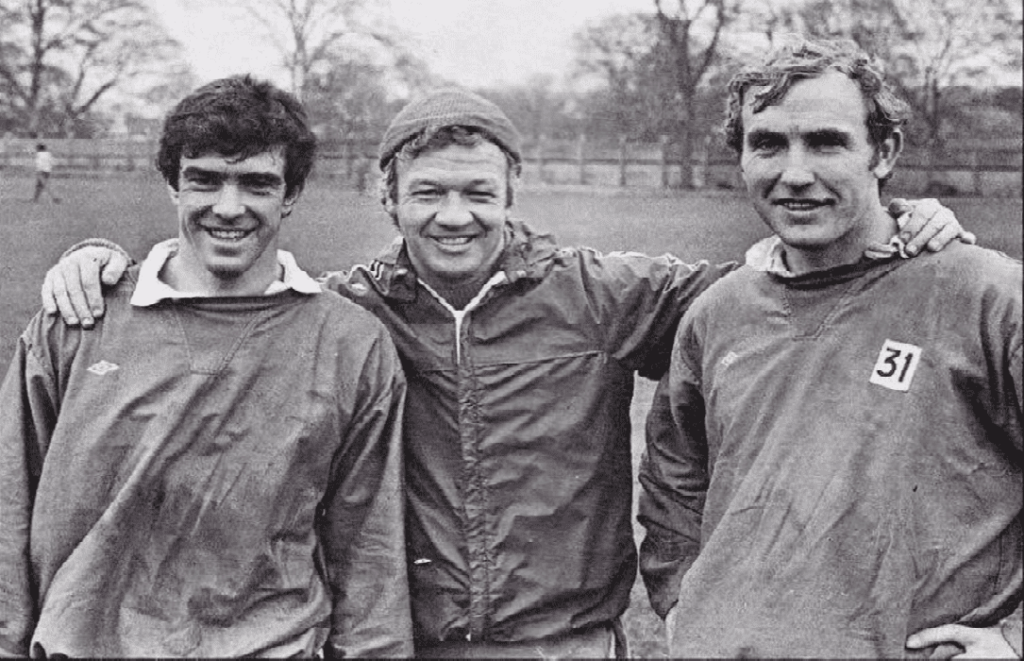

Fred Pickering, Alex Scott and Jimmy Husband

2 March 1966

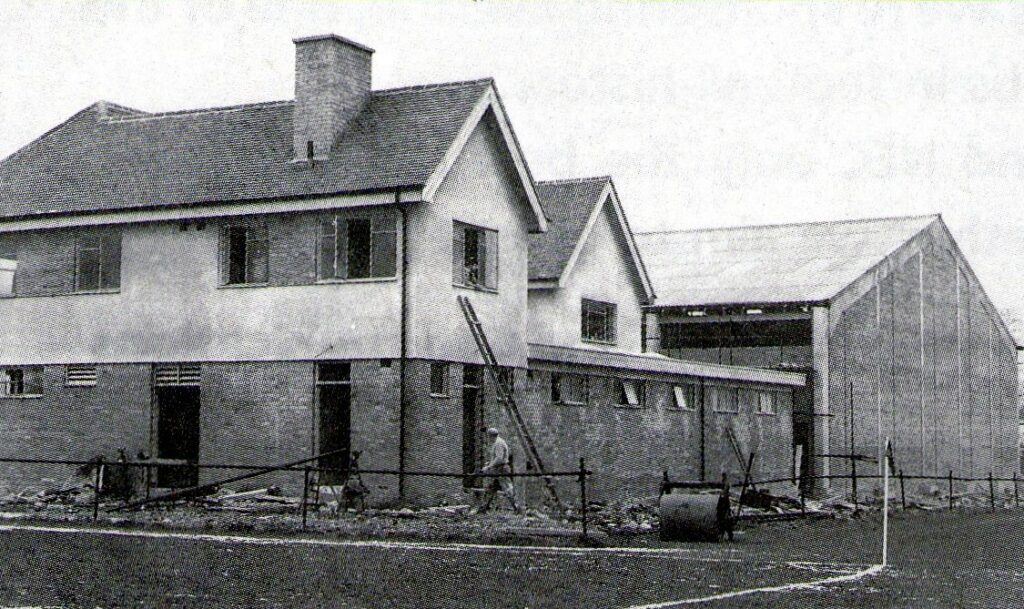

The financial future of the club was on a sound foundation, thanks to the investment and guidance by Mr Moores, and the developments at Goodison and Bellefield – now well underway – continued uninterrupted by his shock resignation. By early 1966, they were almost complete, as this detailed interview with Harry Catterick by Michael Charters of the Liverpool Echo reveals;

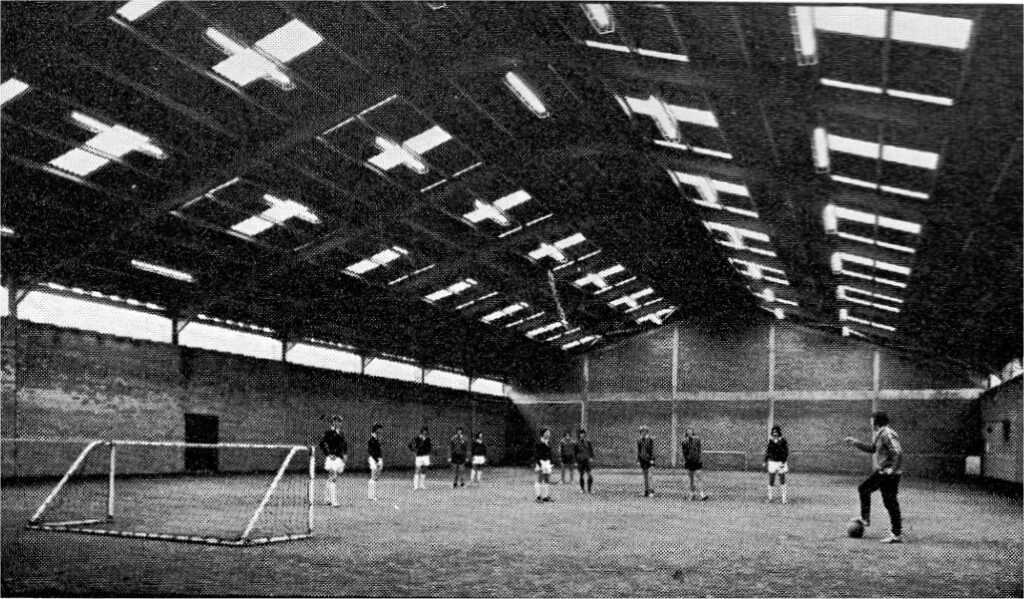

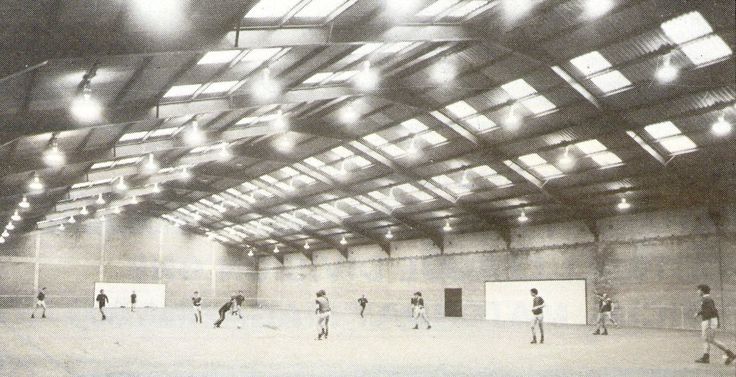

EVERTON PLAY INDOORS

By Michael Charters

“Work will be completed soon on Everton Football Club’s training ground at Bellefield, West Derby, which will make facilities there the best in Britian. When it is complete, the club will have achieved the ultimate in training arrangements, with the players only reporting to Goodison Park on match days. At present, the playing staff arrive at Goodison each morning and are taken by coach to Bellefield for training, returning to headquarters for baths and a mid-day meal. But within the next few weeks, Bellefield will become a self-contained unit. The players will report direct there each morning, train, bath and have a meal in a pavilion which sets a new standard in dressing room accommodation.

The most notable feature of the work, however, is a superb indoor playing area, which resembles an aeroplane hangar in size and scope. It is 200 feet by 100 feet, with the roof towering more than 60 feet above an all-weather playing surface. The walls have been left bare so that the ball can rebound truly off the surface. Every conceivable type of training exercise can be conducted there without interference from the weather. Other clubs, including Burnley and Arsenal have indoor playing areas but none compare with Bellefield in size and usefulness. Linked by a canopy to this building is the pavilion. This has two sets of dressing rooms and baths, tiled from floor to ceiling, treatment rooms, and equipment rooms. The players will be able to move from there direct to the indoor area without being troubled by weather. Upstairs, there is a dining room, superbly-fitted kitchen, a lounge for the players and also a room for the manager, Mr. Harry Catterick, who will work from there instead of his present office at Goodison Park. The office has been designed in a corner of the building, with two windows overlooking the two outdoor training pitches, so that the manger will be able to get an overall view of activities outside.

(Liverpool Echo and Evening Express, 18 January 1966)

Mr. Catterick told me; “I will be able to supervise the training schedule with the coaches as well as attend to routine office work.” The present wooden pavilion, built more than 30 years ago when the ground was used by a shipping company as a sport field, is to be pulled down. A car park will be constructed on the space. The cost of this work is in the region of £100,000. For that, Everton will not only possess the finest training ground in the country, but also a centre which should being the club untold benefit in the future.

Mr. Catterick explained; “At present, we have to train in all sorts of weather conditions throughout the winter. Now, by using our indoor pitch, we will be playing on an absolutely true surface instead of either mud or frost. “The fact that the ball bounces truly will be of the greatest benefit to our current players, particularly the youngsters learning their trade, and all the boys who will come to us in future. They will have superb conditions in which to train and improve. “Years ago, far-sighted directors established our ground at Goodison Park, which is acknowledged to-day to be one of the finest grounds in the country. Their business acumen has paid off a thousand-fold, and we believe that future generations of Everton players will benefit in the same way with our new training facilities. We believe we have set a pattern which other League clubs will follow.”

Everton first used Bellefield for training 20 years ago, when they leased the ground. Before they decided to spend £100,000 on these improvements, they negotiated to buy Bellefield three years ago at a cost of £30,000. It is money well spent.”

Liverpool Echo and Evening Express, Friday, 11 February 1966

– Jimmy Gabriel takes a shot (left) while Alex Scott (right) looks on.

Liverpool Echo, 16 July 1966

– the morning after Brazil were unceremoniously dumped out of the World Cup by Hungary at Goodison

The Opening of the New Bellefield Training Facilities – July 1966

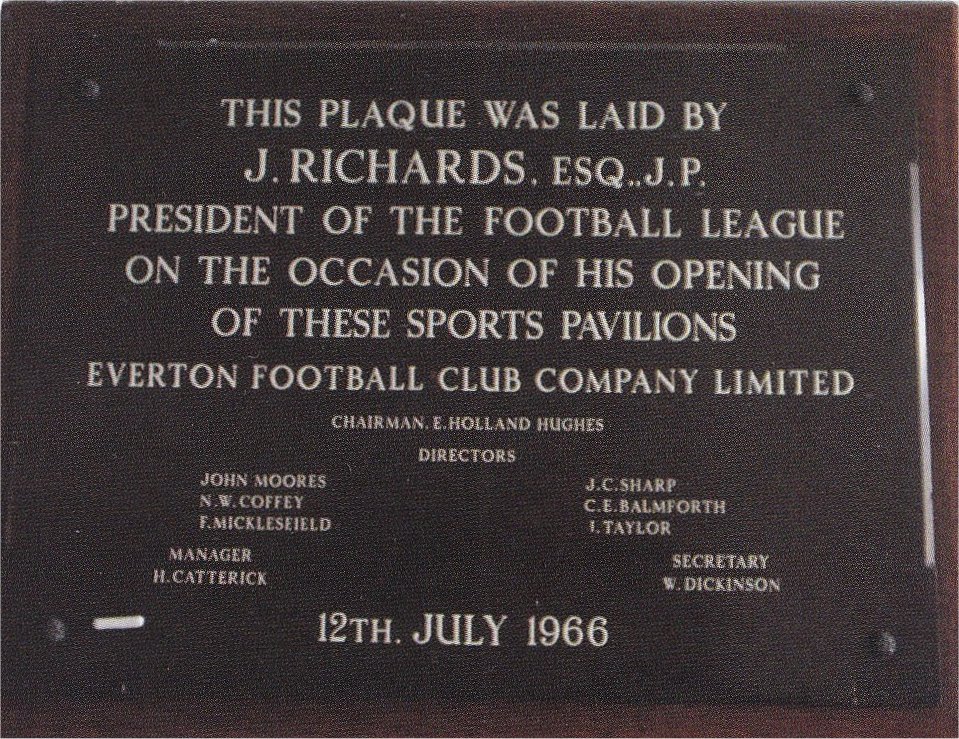

Bellefield was ready later that summer. On 12 July 1966, the new facilities were officially opened by Mr Joseph Richards, the President of the Football League, who was fulsome in his praise for Everton’s foresight and initiative as he unveiled the plaque;

“Everton will be the envy of the soccer world with this possession. Such improvements and progress are necessary in football if Britain is to compete with the world. This is a most enterprising move for Everton, one of our greatest clubs, and a tribute to the team-work of the directors and the ideas of manager Harry Catterick. I only hope other clubs will follow Everton’s pattern and provided similar facilities.”

After Sir Joseph had declared the ground open, the guests inspected the whole project, which cost some £130,000, including the cost of the freehold of the land. The party included all the Liverpool directors, headed by president Tom Williams and chairman Sydney Reakes with Mr Shankly, while also present was Mr Alan Hardaker, secretary of the Football League, and Mr Sam Bolton, a member of the League Management Committee.

They were shown round Bellefield by the Everton directors, Mr Catterick, trainers Tom Eggleston and Gordon Watson, coach Ron Lewin and physiotherapist Norman Borrowdale. The dressing room pavilion, complete with dressing rooms for four teams, treatment room, kitchen and dining room were loudly praised.

Sir Joseph was presented with a gold cigar cutter by Mr John Moores, former Everton chairman, whose part in this superb Everton project was referred to by Mr E. Holland Hughes, the club chairman. Mr Hughes said that it had been Mr Moores who had inspired and directed the Bellefield improvement. The ground would be a memorial to the magnificent services he had given and was giving to the Everton club. Everton would always be in the debt of Mr Moores for his encouragement and guidance. He also thanked Mr Catterick whose advanced ideas on what was required in modern training methods had been incorporated in the new building. Mr Moores thanked Sir Joseph for declaring the building open and paid tribute to his services to football in general.

Michael Charters reported,

Before the opening ceremony, the Everton club gave a lunch at the Adelphi which was notable for its friendly atmosphere. It was particularly pleasant to see the amity between the Boards of both clubs, both working for the all-round improvement of football in this City. I have already written earlier this year in detail of the Bellefield improvements, which set a pattern in Training ideas. In this Mr Catterick’s part cannot be over-stated, for with the consistent encouragement of Mr Moores, he has been the one whose suggestions have been followed by the architecture in design and outlook. The public don’t get a chance to see this, as they can with work at goodison Park, but Bellefield is now the last word in training grounds.

Liverpool Echo, 13 July 1966

Sir Joseph Richard’s speech was all the more poignant given that just a few hours later, world champions Brazil would be playing Bulgaria at Goodison Park in their World Cup group match. And all this just two months after Everton had lifted the FA Cup at Wembley, and only two weeks away from England’s World Cup triumph. These were heady days indeed.

Later John Moores was keen to give recognition to the key role played by Catterick,

Harry had tremendous enthusiasm and dedication. He was totally committed to the job. He never spared himself at all. He put Everton on the map again and played a big part in the development of Bellefield, giving us the facilities to train the players in the best possible way, whatever the weather, and also to develop young players for the future. Harry was a perfectionist.

(Photo by W & H Talbot Archive)

(photo: Rob Sawyer)

Catterick was not a tracksuit manager and the players saw more of their trainers during the week. Training was taken by former Sheffield Wednesday coach Tommy Eggleston, and Wilf Dixon, who made sure it went exactly to the manager’s requirements. When he did don a tracksuit, it was often for the benefit of the media, and players would often joke ‘The Catt’s got a tracksuit on…the BBC or ITV must be here!’ (9)

Harry’s usual attire was an immaculate suit and tie, and met with the coaches every morning to discuss the plan for the day and how long would be spent on routines, before they reported back later to tell him how training had gone.

His office, which had an outside metal staircase leading up to it, was situated on the corner of the building at Bellefield so he could see virtually everything from his windows. One part he couldn’t see was an old bowling green where we’d play five a side. Harry would suddenly appear from nowhere and as soon as he was spotted the pace of the game would increase about 100 per cent and the ground staff, who’d been watching, would start working away! When The Catt got the gym built I’m sure he got a set of tunnels built as well because he can appear anywhere, at any time, without warning.’ (9)

According to Colin Harvey, ‘Before Bellefield was redeveloped we spent more time at Goodison. He used a board with football pitch markings to give us his match instructions and when we moved to Bellefield permanently he had a similar table and also had a magnetic wall-board with model plastic players. Harry was very thorough in how the opposition were going to play and how we would counter it.’(9)

When I signed, Bally gave me some of the best advice anyone could give. ‘Don’t take the ball off Johnny Morrissey in training.’ Johnny was a fearsome character and you wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of him. He did not suffer fools gladly. I’ve seen Johnny chase people around Bellefield simply for tackling him; Terry Darracott was one who was naïve enough to try it. We were his team mates too; among opponents he was hated and feared. He was number one in Jackie Charlton’s ‘black book’ and completely ruthless. Luckily, I was warned before it was too late.’ – Howard Kendall with James Corbett, Love Affairs & Marriage: My Life in Football (2013), p.36

Catterick was enigmatic. We feared and respected him. He never ranted or raved and was always straight to the point. There was never any arguing with him and you had to be respectful because of his record. But we didn’t know him at all. He was distant and we’d rarely see him on the training ground. But we knew he was there. You’d see the blinds twitching in his office at Bellefield and step up the pace because you knew he was watching. He wasn’t someone you’d warm to. Even his own staff didn’t like him. But he knew what he was doing: you don’t win two League championships if you don’t know what you are doing. Howard Kendall with James Corbett, Love Affairs & Marriage: My Life in Football (2013), p.38

Catterick was rightly proud of what he had created at Bellefield. His plan for a ‘Football Factory’ had come to fruition. This could not have been done without the help and support of his backroom staff who were undoubtedly crucial to his achievements. Tommy Eggleston was a significant loss when he left to manage Mansfield in 1967, but Wilf Dixon was more than able to step into his shoes, and was appointed Everton first-team coach in his place. Over the next four years he would become the principal link between Harry and the first-team players, and would play an integral role in the forthcoming successes.

(left to right) Joe Royle, Roger Kenyon, Alan Ball, Alex Young, Johnny Morrisey, Jimmy Husband

Left to right: Alex Young, Alan Ball, Jimmy Gabriel, Jimmy Husband and John Morrissey. 14 February 1967.

This period also saw the emergence of ‘The Holy Trinity.’ Interviewed a decade later by John Roberts, Catterick recalled,

This was something we worked on particularly in the indoor area with three and five-a-sides, with the ball going at lightening speeds. I saw games in there that were, to me, unbelievable. They weren’t very big physically, so they had to be quick and skilful to get by – and, by God, they were! The ball would almost go one touch and that’s where they developed – these three players in particular. They really worked at it; you wouldn’t see them passing nonchalantly at any time – they always passed it precisely and sharply. That is why they became a really important trio and they appealed to spectators more than the front runners who normally get the glamour.

Rob Sawyer, Harry Catterick (2015), p.127

“My boss at Everton, Harry Catterick, believes that the most satisfying thing for a manager is to watch a boy develop from a member of the ground staff into a fully-fledged first-team player and maybe even an international. To watch a youngster step through the gates of our Bellefield training centre as a wide-eyed innocent 15 year-old and then, in a few short years, see him step on to Goodison Park four miles away, and hold his own against some of the best players in the world, reflects tremendous credit on the club.

For years our club was associated with big-money transfers and it is a fact that Mr Catterick made some spectacular swoops. I was one of them. But these headline-making deals tended to obscure the fact that we have a lot of home-produced talent at Everton. Of the 14 players mainly involved in bringing the championship to Goodison in 1970, eight of them came through the ranks. Tommy Wright, Brian Labone, Colin Harvey, Alan Whittle and Joe Royle are all Liverpool-born lads who joined the club from local schoolboy football. John Hurst and Roger Kenyon are from Blackpool and Jimmy Husband from Newcastle.”

Alan Ball, Everton v Chelsea matchday programme, Premier League fixture, Sunday 30 April, 2017 (from an interview with Ball in a 1971 football annual)

In 1969, one of those youngsters with potential was Stan Osborne, a fifteen-year-old Kirkby Schoolboys starlet, who had been scouted, along with a few of his team mates, and invited to attend training sessions at Bellefield. He wrote about that period in his life many years’ later, in his book Making the Grade, published in 2012. In it he described his arrival at Bellefield for the first time, and the tour of the complex;

‘Together with Kirkby Boys team mates Ray Pritchard, Paul McEwan, and Eddie Avis, I caught the two buses from Southdene, in Kirkby to the West Derby area of Liverpool, where Everton had established their state-of-the-art facilities. Tucked away, almost secretively, behind a rectangle of neat suburban semi-detached houses in this leafy corner of Liverpool, it was easy to miss the entrance gates, which were squeezed into a gap just the width of a team bus, between two of the houses bordering the complex.

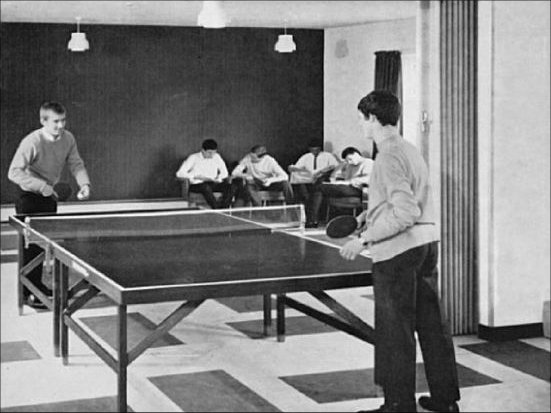

During our first visit we were met by Arthur Proudler, a cheerful balding, smiling, track suited coach of about forty, who addressed us in a soft Birmingham lilt explaining what we could expect when training at Bellefield. We were impressed when we were shown around the facilities. Immediately inside the gates, the drive led past the groundsman’s house toward the modern grey brick-built buildings. To the right of the driveway was a full-sized training pitch, immaculately laid out with gleaming white posts on a lush, green turf. Beyond this pitch, another equally impressive one was set out at right angles with just the one goal visible as it continued around the back of the main building. To the left of the driveway, was an area which looked as if it was used for five-a-sides matches, and another narrower area of grass continued around the back of a massive structure, which contained a large indoor all-weather gravel pitch. To the right of the building which housed the indoor pitch, a corridor connected it to a two-storey building containing the changing rooms on the ground floor. There were four in all, arranged in two pairs with luxurious communal shower and bathing facilities for each. A kit/boot room, drying room facilities, a trainers /referee’s changing room and a Physio and Treatment room completed the downstairs of the complex.

Upstairs we were shown the Player’s Lounge, which contained a table-tennis table and an array of comfortable seats and chairs. Across the landing was another set of rooms, which housed the kitchen and dining facilities along with office accommodation, including an area we weren’t allowed into. The plate on the door saying ‘Manager’ needed no explanation.

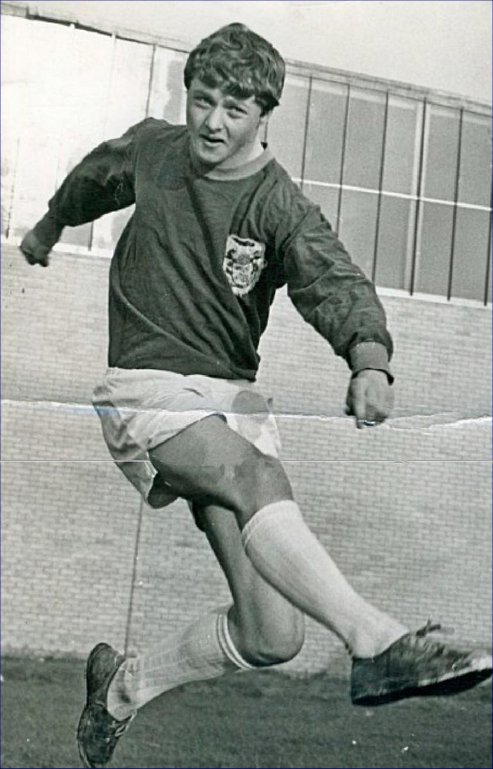

as a young teenage prospect for Kirby Schoolboys

As a wide-eyed, innocent fifteen year old, who had been a fanatical Evertonian all my life, I found the guided tour of the training ground a little bit awe-inspiring. If I was in any doubt about the size and stature of Everton, seeing and using the training ground and experiencing the environment first hand underlined the fortunate opportunity that was presenting itself.

The training sessions themselves were nothing out of the ordinary and always took place in the indoor area. The trainer, usually Arthur Proudler, put the group, normally of around sixteen schoolboys, through a series of warm up exercises followed by drills and practices designed to assess and improve our technical skills and ball control. This was always followed by a seven or eight-a-side indoor game, often under conditions, such as one or two-touch, to sharpen our play. We also noticed that the trainer, or someone assisting, would always be observing us closely, making notes on individuals, presumably for discussion about the progress we were making.

Needless to say, Eddie, myself, Ray and Paul threw ourselves wholeheartedly into every session, trying desperately to impress the coach and attempting to secure ourselves the chance of an apprenticeship with Everton. We were always thanked for our attendance at the ended of each training session, but we were never given any feedback about how we had performed, or given any indication as to our chances of being signed on.’

Stan Osborne, Making the Grade (2012), Ch.1

Ken Rogers, a young reporter in his first year at the Liverpool Weekly News, later to become Chief Football Correspondent and Sports Editor at the Liverpool Echo, did not find it easy to get through the doors at Bellefield, never mind interview the Everton manager with a known dislike for the press. Bellefield had become known as ‘Colditz’ to even the most hardened of national journalists, such was its impregnable reputation. Rookie Ken, just nineteen years old, was determined to get a interview with the ‘Catt’ – Harry Catterick – and telephoned his Bellefield secretary Jean, twice a week for six months, but the answer was always “I will ask the boss and let you know.” But the call never came. Finally, just days before the derby match in December 1969, Jean did speak to the boss, who offered to do an interview, provided it was done at noon that day. Ken wasn’t going to pass his chance up, and hot-footed it to the bus stop to catch the 75 bus to West Derby. Ushered into the small office, Ken was met with an abrupt “What do you want?” before he attempted to gain some insight into the preparations and expectations for the derby. But to Ken’s dismay, all of his twenty carefully prepared questions were largely met with monosyllabic replies, and he found himself guided out of the office two minutes later and down the back stairs to avoid contact with the players coming in for lunch. On the 75 bus back, he had plenty of time to ponder about the derby exclusive that might have been.

‘My first experience of the Everton training set-up came in the 1967/68 season when, as a raw nineteen-year-old sports reporter working for the now defunct Liverpool Weekly News, I found myself mixing with some of the biggest stars in the business as I sought to claim some exclusive interviews for an audience of little more than 15,000 readers. The likes of Ball, Harvey and Kendall could easily have brushed me aside as an irrelevance compared with some of the more experienced national hacks who frequented Bellefield in search of exclusive stories and interviews.’

Of course, access improved down the years, and Ken particularly enjoyed his daily meetings with Howard Kendall and Colin Harvey in the 1980s, in that same Bellefield office he’d found so difficult to penetrate in the late sixties. Nevertheless, it wasn’t always easy access, most notably when Billy Bingham banned the press from Bellefield, as did Joe Royle almost two decades later, after what he believed was a vendetta against him.(10)

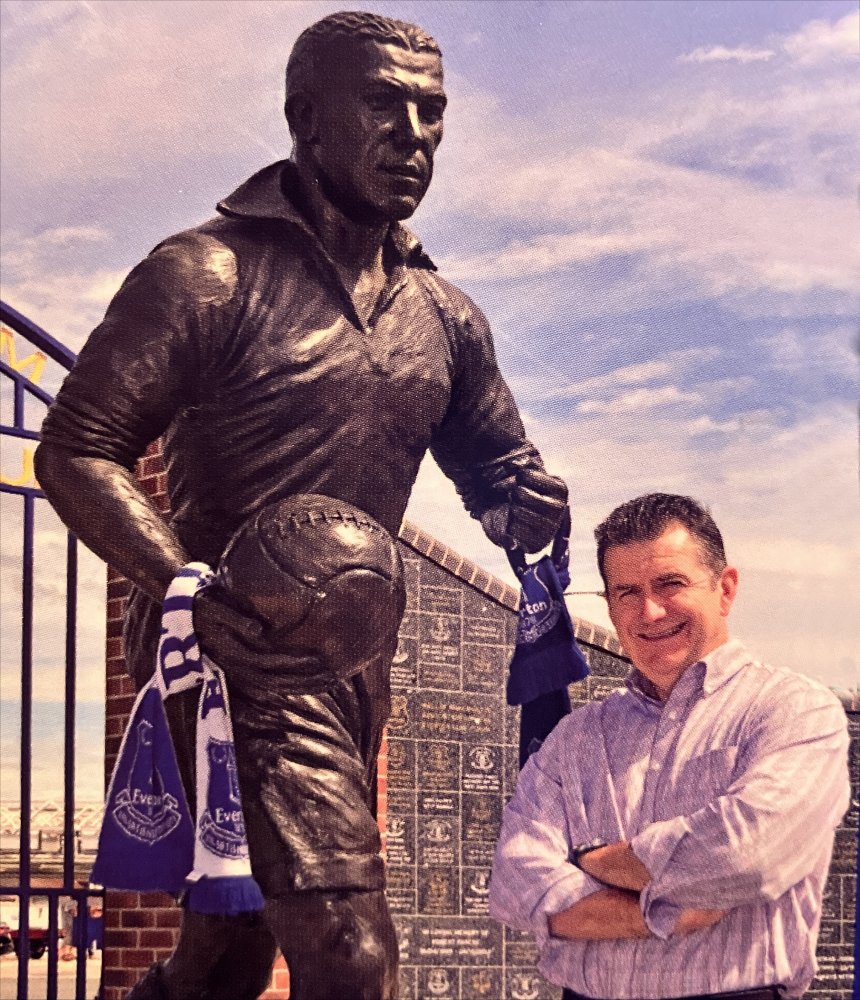

Ken is now ‘retired,’ but still writes a weekly column for the Echo, continues to research and write about the local Everton community where he grew up, and chairs the Everton FC Heritage Society. He has been an Everton fan all his life, and still holds a boyish interest for every aspect of the club, despite his years. He declared,

‘Down the years, Bellefield became part of my life. Throughout the 1980s, with Howard Kendall at the helm and with Everton enjoying its most successful period ever, I effectively lived the history of the club on a daily basis. I would sit in the dining room (an absolute no-no during Catterick’s days) and track every aspect of club life for the readers of the Echo. Bellefield is no more, but my memories are vivid. The first player I interviewed there was great goalkeeper Gordon West. I conducted the last interview with ‘Golden Vision’ Alex Young at Bellefield, before he stunned the Goodison faithful with a move across the Irish Sea to Glentoran. But that was life at Bellefield. It now takes its place in Everton history, full of secrets and inspirational stories that are now part of the history of the club.’ (11)

Just as Ken had made his way through his apprenticeship at Bellefield as a young reporter, so did David Prentice, although by then he already had the experience of reporting for the Southport Visiter and the Liverpool Daily Post, before moving to the Liverpool Echo in 1989 as sports sub-editor. When Ken was appointed sports editor, David stepped into his role, with his first match as the Liverpool Echo Everton correspondent on 20 February 1993. He spoke of those early days at Bellefield,

As was the routine under Joe, and then Howard, followed by Walter, and last of all David, I would be ushered upstairs by Bellefield secretary Mary, crossing the dining room where a handful of players were eating breakfast, and entered the little office that had been used by a succession of Everton mangers since Harry Catterick. The glass-topped table with the football pitch underneath the see-through surface had been replaced during Mike Walker’s era by a more traditional wooden desk, but otherwise the scene was as it had been since Bellefield’s construction. But Joe’s demeanour was altogether more cordial than Catterick’s had ever been with the media. “Hello son. Cup of tea? What can I do for you?” Joe supported me throughout his tenure. And I supported him. And in doing so I felt in no way compromised. But I criticised whenever I felt that the circumstances were justified. (12)

………………………………………………..

Bellefield in the Seventies

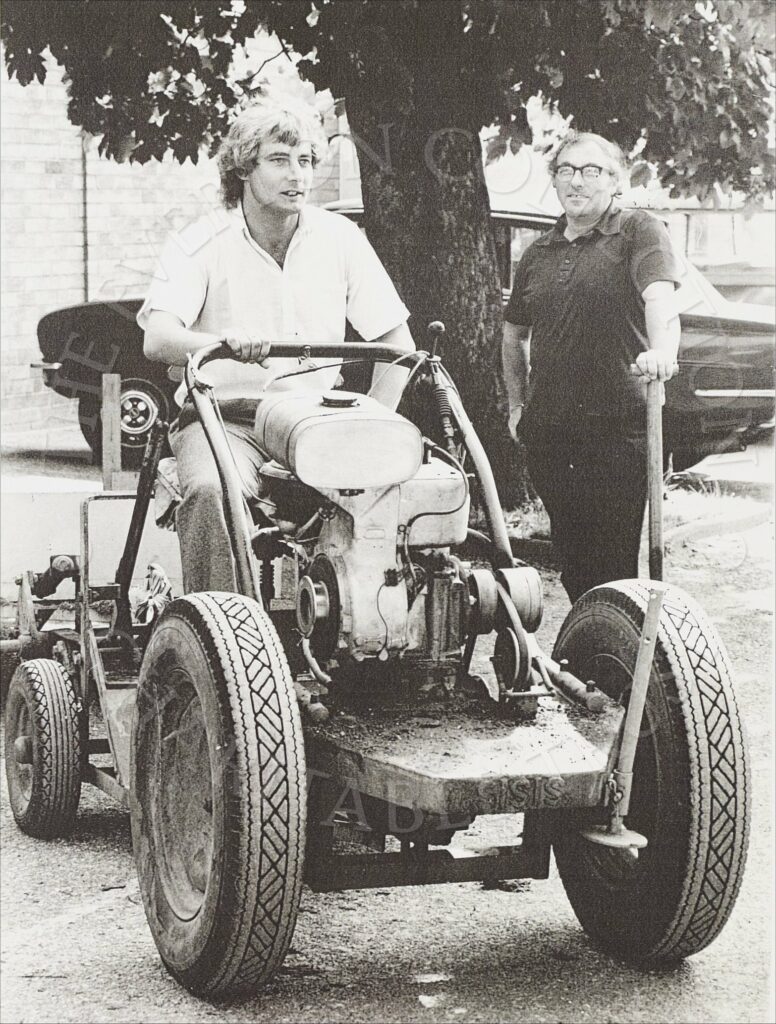

– although the unsuspecting Roger looks as though he is about to lose his shorts

The swift demise of the great championship winning side of 1970 has been the subject of endless debate and discussion by Everton fans for over half a century. Howard Kendall later reflected,

‘The great mystery was not how we won the League Championship in 1970. It was how we didn’t win more in the years that followed…. I think there was also probably a bit of staleness on the training ground too. It was still a lot like when I started out at Preston a decade earlier. Wilf Dixon knew the game, but he was a trainer first and foremost, and would work us hard. On a Tuesday morning, it’d be sprints: 8×80’s, 4×40’s, 2×20’s, 100 yards. People would be sick behind a tree. I’ve seen Joe Royle absolutely spewing up behind a tree; Westy too. We had a running track at Bellefield with sand on it, and we’d pair up, and Wilf had the stopwatch; one player would go round, then his partner would go round, so you had little bit of respite.

And Tommy Wright wasn’t too good one morning, so he went round once – he was pairing with Colin – and he flopped behind a tree. So Colin went round and round and round. There’d be no Tommy, so Wilf would shout, Colin’s got to go again…Colin you’re slowing up…Your time’s not good enough.’ Colin, who was a great trainer, was absolutely shattered, while Tommy was sat behind a tree.’

I never liked the running side of the training ground routine. It’s why, when I went into coaching and later management, I did most of it with a ball. The more interesting you make it, the less players know they’re working hard; even if they might be doing the same amount of exercise as on a cross-country, or 800 metres routine. It kept them fresh, and it kept them motivated. I’m not saying we lacked motivation as players, but sometimes there’s a need to freshen things up. from Howard Kendall (with Corbett, James), Love Affairs & Marriage: My Life in Football (2013), p.60-62

John Robinson, a former Everton youth player, remembers his time at Bellefield very clearly.* He played regularly at Bellefield in the mid-seventies with his younger brother Neil, but fluctuating fitness levels causing a lack of confidence hampered his progress, leading to his eventual release. Nevertheless, he frequently trained with the first team players and took part in mixed games that brought him up against some of the inspirational players from his early teens. John played in a youth side at Bellefield for half a season, where he regularly featured in defence alongside Ken McNaught in the centre, with Dave Jones and Neil as full backs. After leaving Everton, John played professionally in the USA league. He recalled Neil once coming home from a training session at Bellefield in 1974. Visibly upset, he sat down to talk to his father. By now almost in tears, he eventually revealed that he’d learned that day that Colin Harvey, his hero who he looked up to every day on the training pitch, had been sold to Sheffield Wednesday. He was devastated. Eventually, to get him off the subject, his father asked him what else had happened at training. Neil replied, ‘Oh yes, I signed professional forms today.’ Such was the magnitude of the loss of his hero, it had completely overshadowed the dream that Neil (and his family) had since he was a youngster, to sign for the team he loved.

*[I personally have great memories of John bossing the midfield in our school first team (Wade Deacon Grammar in Widnes) like some early Valderama with his bushy red hair cutting a striking figure. His father was the former head barman of the Winslow, and John’s brothers would become well known – Professor Sir Ken Robinson (also ex-Wade Deacon) as a renowned educationalist, and younger brother Neil, born in Spellow Lane, who was on Everton’s books between 1974-1979, playing seventeen times, before making his name in the successful Swansea side under John Toshack. Another brother Ian, was a musician in local bands, later founding and playing with tribute band ‘Rumours of Fleetwood Mac’ for many years].

(Southampton v Everton, 17 February 1979. Photo: Southern Daily Echo)

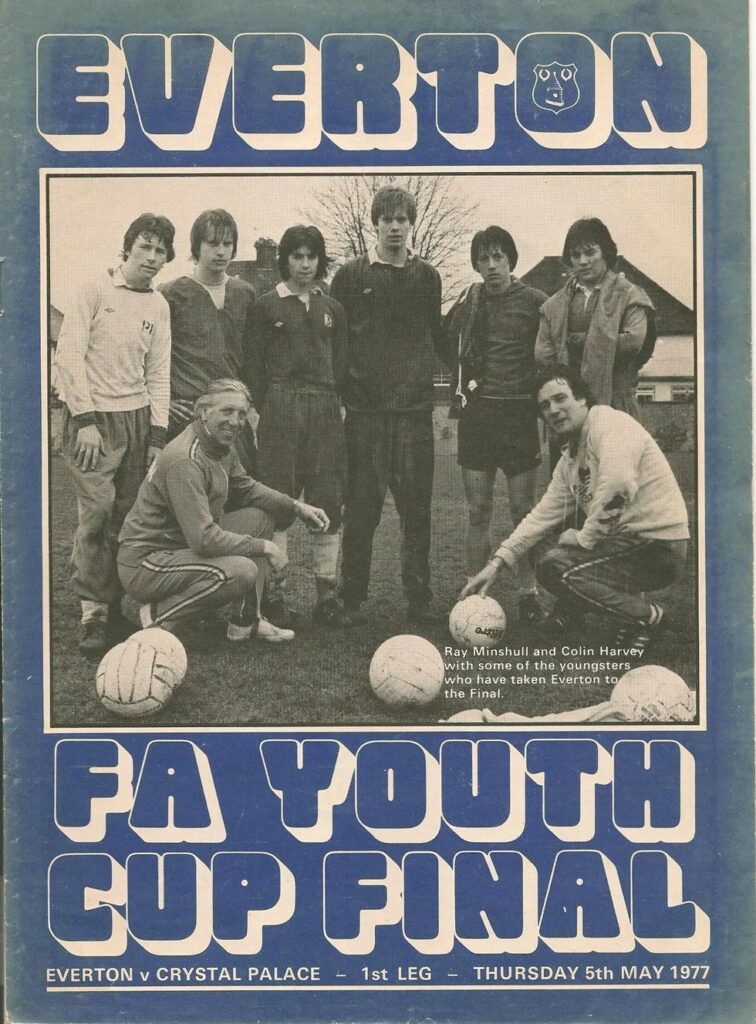

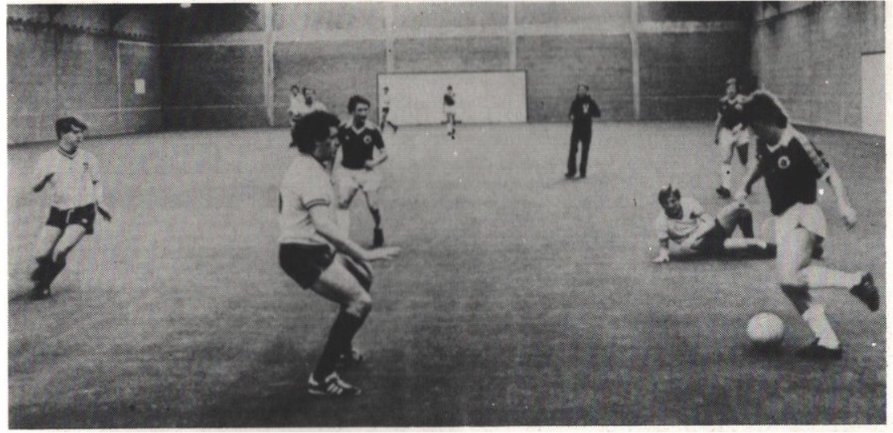

Coached by Ray Minshall and Colin Harvey

‘It was quite remarkable the first time I went to Bellefield, I had never seen the place in my life and I walked in there and really, it was state of the art. It was sumptuous. I had never seen an indoor gym like it, they just didn’t exist at the time. It was incredible; you could have a full-blown practice match in there if it was raining outside.There were a number of weight rooms. At the bulk of clubs, they just didn’t have these types of facilities. Weight rooms were reserved for dingy rooms underneath an old concrete stand. I had just come from Leeds United, the champions at the time and they just didn’t have anything like it. Even the big teams in Europe didn’t have facilities like Bellefield.’

(left: Duncan pictured at Bellefield with George Telfer and Neil Robinson)

‘Bellefield had this warm-up five-a-side pitch that we called ‘Little Wembley.’ You have to remember that in those days and in the seventies generally, by October there wasn’t a blade of grass on most pitches, but our ‘Little Wembley’ was always in pristine condition. It was really like a bowling green.

There was a real old community atmosphere up there and I picked up on it straight away. Right from all of the girls on the desk and the ladies in the canteen, they were all a good laugh. We’d get beans on toast, mainly fibre foods. Although I have seldom been there since leaving the club, every time I do go, I am welcomed with open arms. That is what made Bellefield so special.’

Duncan McKenzie in Simon Hughes, Bellefield Secrets (2007) p.28-32

Bellefield in the Eighties

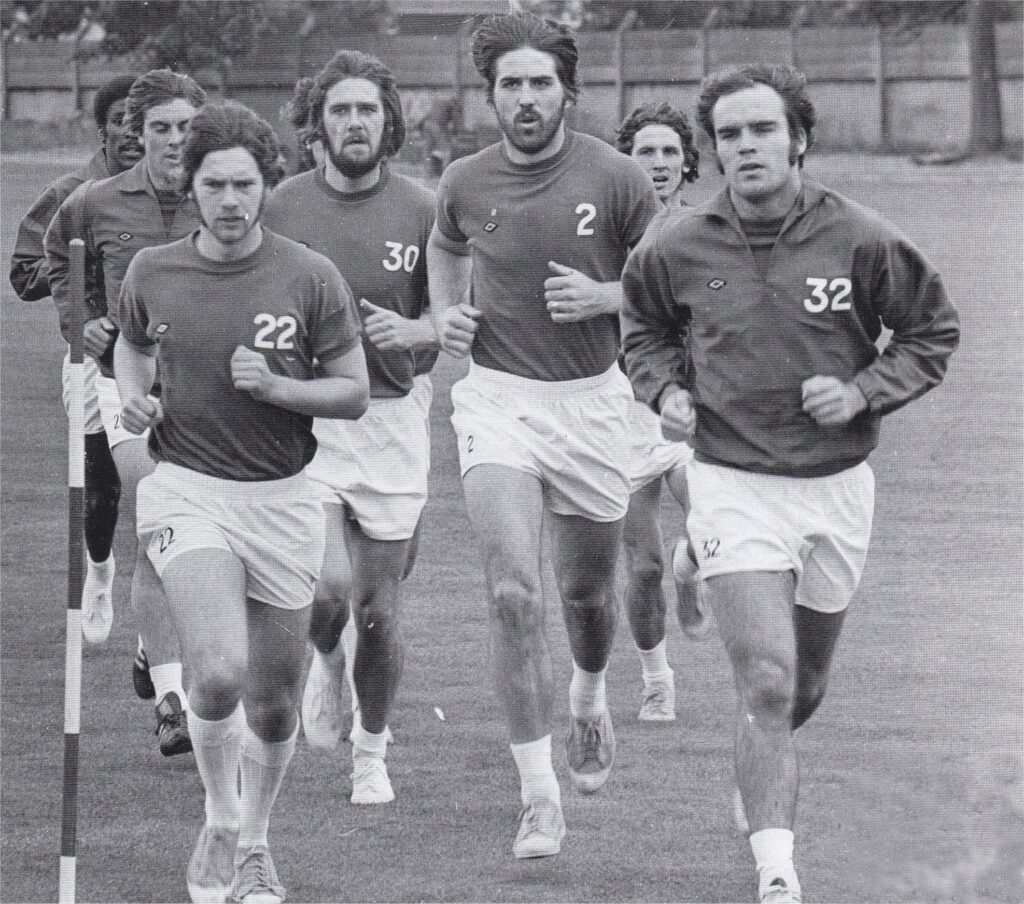

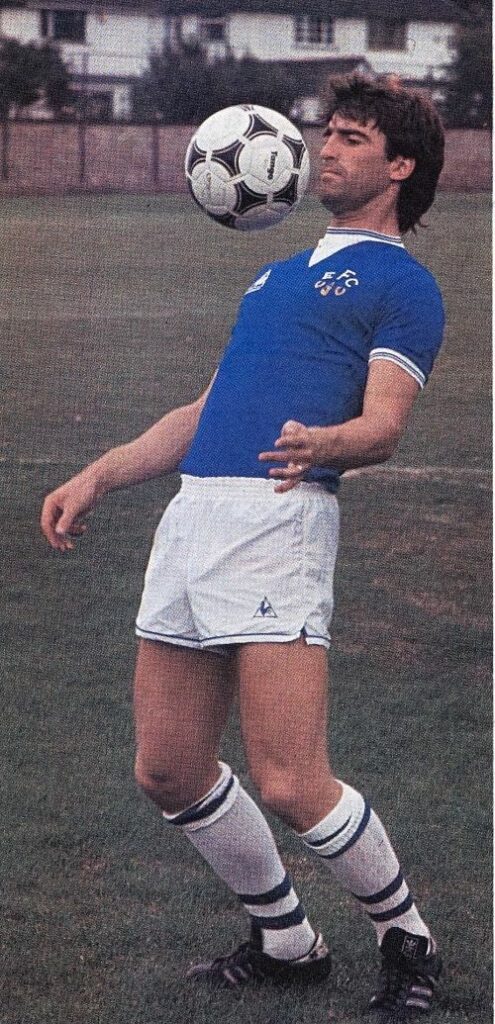

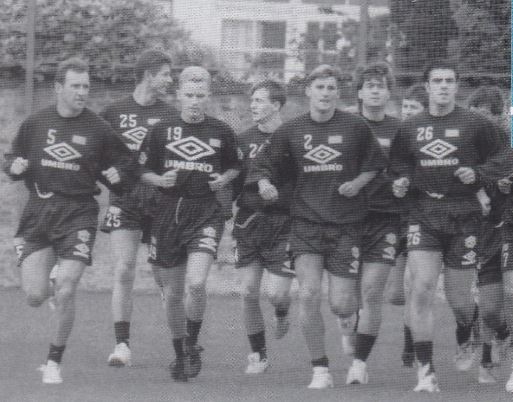

With the training lines led by John Bailey and Alan Harper

Thursday, 15 November 1984. (Photo by Bryn Colton)

“The players spent more time at the training ground than at Goodison, so I’m sure most of the lads would agree that they have more happy memories at Bellefield. The atmosphere was always brilliant. It was like a community atmosphere. Bellefield was just a great place to be. It was made a more special place to me by the fact that when I was there, we were very successful. It actually got to the stage where players wanted to stay there as late as possible. We were doing well, winning trophies and the team spirit was unbelievable, so as footballers, why would we want to spend time anywhere else?

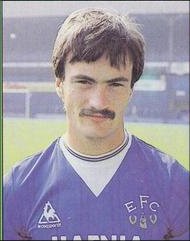

(Right) Kevin Ratcliffe at Bellefield

The things that Howard and Colin implemented at Bellefield certainly brought my game on an unbelievable amount. The standard of training actually got better and better throughout the 80s, and the tempo on any average day was scary. It was always good fun too. Colin Harvey as an innovator was brilliant at coaching sessions. He was particularly influential during pre-season where we used to play matches all the time. A lot of clubs now just don’t seem to touch a ball for weeks when they start pre-season, but Colin used to get us started using the ball early on. We used to do twelve minutes of solid running, then Colin would get the footies out and we would play hard. Every session Colin arranged was enjoyable and fun. Even when it snowed, he would make us play with the ball. I remember getting to Bellefield one day and it was snowing really heavily. All of the pitches were unplayable really, but Colin didn’t care. Out came the tango footies. They were great times.”

Kevin Ratcliffe, in Simon Hughes, Bellefield Secrets (2007) p.50

I spent a year with Colin Harvey while he was reserve coach, and he really, really developed me. He made me a better player, a more aware player. You ask anyone who came through the Colin era and they’ll always say he was the best coach they’d worked with…He made me understand what I needed to do. He would launch balls to me and Mick Ferguson, or there’d be one-on-ones with Alan Irvine or Alan Biley running at me. It was if I was an apprentice again going back to basics.

Derek Mountfield in Simon Hart, Here We Go – Everton in the 1980s (2019)

‘On my Everton debut I was up against Alan Ball at Southampton. I could run, but I couldn’t get near him. He was playing one touch all night. For me it was an education. When I went to Everton, I was very much a runner. I covered incredible amounts of ground, made the box every time. But I suddenly started watching Colin in training. The amount of times he and Howard stood still was another learning process for me. Colin and Howard were still the best two players, I am not kidding. If we were picking sides for a game and those two were playing, they were first pick.’

‘Colin would take us together and we did something a lot of people do now, but in those days didn’t. I would play just behind Graeme Sharp and would drop deep as though going for the ball, but instead it was played up to Sharp with me spinning back up to support him. When we played against Hansen and Lawrenson, they always found it really difficult, because centre backs don’t want to go in and leave the other one exposed. They like to stay together.’

‘At Bellefield, Neville Southall used to chase me around so much. Keepers hate getting chipped in training, but Nev took it to another level. He would not stop chasing, he would just keep running and you know’d know at some stage you were going to have to stop, and when you did, he punched you. Colin and Howard were always petrified he was going to do your ribs in.’

Adrian Heath in Simon Hart, Here We Go – Everton in the 1980s (2019), p.65-71

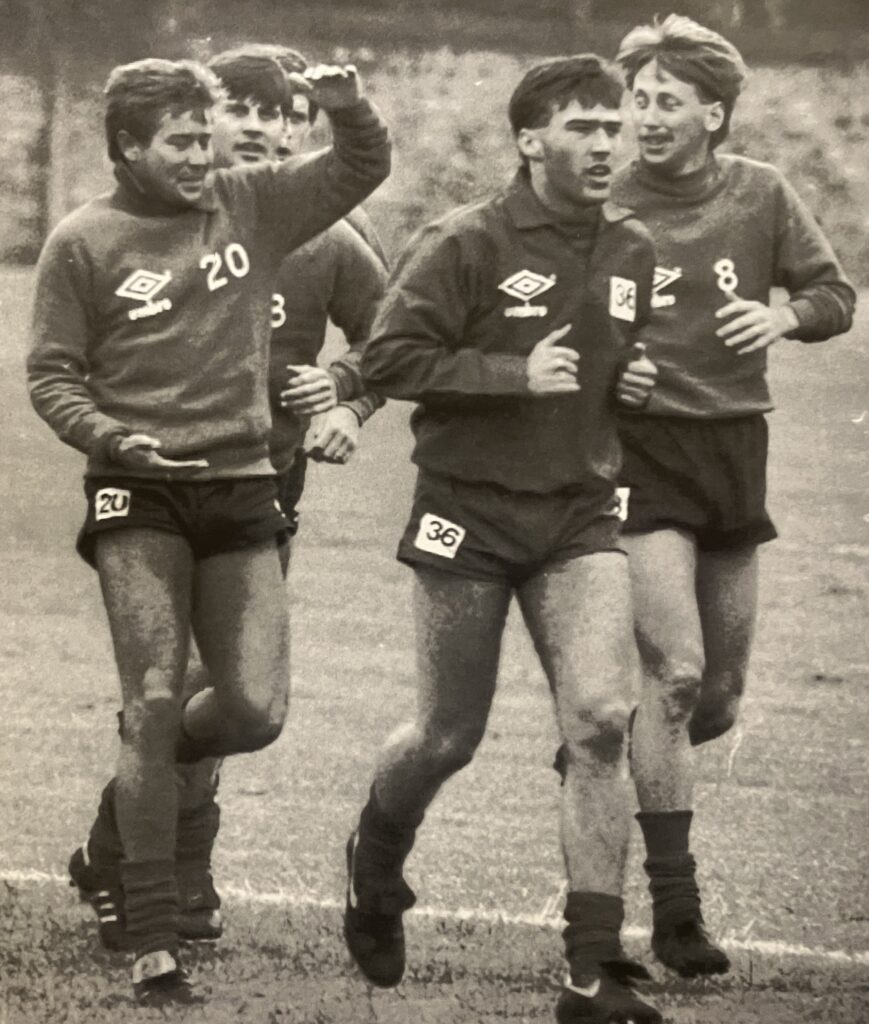

Peter Reid, player/coach; Terry Darracott, assistant manager; Graham Smith, youth coach; and Mick Lyons, reserve team coach (photo Bob Thomas Sports Photography)

(Simon Hart, Here We Go – Everton in the 1980s (2019), p.70).

Bellefield in the Nineties and beyond

In 1990, Neville Southall was becoming increasingly disillusioned at Everton with club’s gradual slide, and slapped in three transfer requests. He was flattered to hear that both Liverpool and Manchester United were keen to entice him away, but he said ‘I work on the basis that if I walked into Bellefield, it felt like home. The day it stopped feeling like home, I could leave. But it never stopped feeling like home.’ (13)

He was with Everton from 1981 until 1998, and he witnessed the Everton management careers of Howard Kendall (three times), Colin Harvey, Mike Walker, and Joe Royle. He is particularly scathing of Walker, whose side were heading out of the top flight until their final day escape against Wimbledon; ‘His training sessions were just rubbish. We had good players and you just have to tell good players what to do – you don’t have show them every five seconds. He didn’t trust the players and didn’t think they were fit, even when he’d been there for a pre-season.’ Southall’s tolerance didn’t survive the one training session they did together despite Walker having been a goalkeeper himself. ‘It was the worst I’d ever had. He had two poles – a grey one here, and a green one there – and if he shouted ‘green’ you dived to grey and vice-versa. We did that for two hours because he couldn’t think of anything else. I said, “Don’t ever bother training me again.” (14)

By November 1994, Everton were bottom of the table before Walker got the inevitable taxi ride. Southall, by then 36-years-old, came to enjoy the next phase as one of his favourites at Everton when Joe Royle was appointed, inspiring a revival which cumulated in the memorable FA Cup Final win over Manchester United in the following May.

‘The simplest things are the best things,’ said Joe on his first day at Bellefield. ‘We’re going to press the other team and were going to play at high tempo.’ So we then set about ensuring we were fit enough. His assistant, Willie Donachie, was absolutely brilliant. He was the first holistic coach I’d come across, and his routines were superb. We played at a high tempo and trained at a high tempo. We trained Monday morning and afternoon, and Tuesday morning and afternoon. We did weights and hurdles, and stuff like that. I thought it was brilliant. I thought, ‘this fellow’s come in; he’s enthusiastic, a proper Evertonian, and he knows what he’s doing, everybody was grafting and grafting; and Joe just focused everybody doing what they were supposed to do. And as we rose up the table, Joe, who was always good for a quip – dubbed us ‘The Dogs of War.’ (15)

“You never imagined Bellefield would be where it was. You just couldn’t have pictured, that beyond the houses would be a great expanse of land which was so well looked after. It was a real homely place, that’s what it was. It was just a much more cosy atmosphere at Bellefield and a lot more relaxed. Everyone who worked there enjoyed their work and looked forward to going in every day.”

Graham Stuart, in Simon Hughes, Bellefield Secrets (2007) p.50

‘Because he’s worth it’

One of the world’s greatest players who came through the ranks at Everton, was, of course, Wayne Rooney. Bob Pendleton, the Everton scout who first saw the youngster at the age of eight, described how it came about;

I vividly remember the first day I saw young Wayne. It was at pitch two on the Jeffrey Humble playing fields in Long Lane, Aintree. I was the secretary of the Walton and Kirkdale Junior League, and I had to go to have a word with Copplehouse Colts, because they hadn’t paid their referees’ fees of £4.50. I was talking to their manager, Big Nev, when I noticed this little striker trying something different every time he touched the ball.

When he got the ball, the ball became his, and when he gave it away he expected it back. He was eight and everyone else was 10, which wouldn’t be allowed now, but he was scoring goals for fun. Big Nev was devastated when I asked about the boy, because he had turned their season around and he didn’t want to lose him, not even to Everton. Fortunately, Wayne’s mum and dad were watching so I invited them to bring their son to Bellefield, Everton’s training ground, later that week. A scout always hopes the parents support the team he works for and it turned out that big Wayne and Jeanette were massive Evertonians. They were delighted when I invited them to Bellefield. We were in.

Before they arrived on the Thursday night I went to see Ray Hall, the youth academy director at Everton, and asked him to sign this eight-year-old on the spot. Ray hadn’t seen him play, but he showed a lot of trust in me and when Wayne showed up with his dad he made a huge fuss of them.

They went to Ray’s office. I remember big Wayne telling his lad to sit up straight and to make a good impression. Then Ray came in but deliberately left his door open. He was up to something. The next thing Joe Royle, the manager and one of big Wayne’s boyhood heroes, walked past and Ray invited him in. Joe was great, really friendly.

Then we signed Wayne Rooney. Belfast Telegraph, 6 Dec 2006

But to the chagrin of every Everton fan, Rooney, who the club had nurtured since the age of eight, headed off up the East Lancs Road in 2004, after making only sixty-seven appearances, scoring fifteen goals. He was still only eighteen years of age.

………………………………………………….

The End of Bellefield

By the time Wayne had moved on, there were plans to upgrade the training facilities for Everton FC and to move to a new larger location. The news was met with an outpouring of sadness and nostalgia, while appreciating the need for a 21st century complex.

Everton’s association with Bellefield finally came to a close on 9 October 2007, ending the club’s 71 year connection with the complex that had commenced in 1936. Bellefield wasn’t just about the players of course. The staff, from those who looked after the pitches, to those who prepared meals and looked after the kit, were all integral to the efficient running of the facility. One of those key figures was Dougie Rose, who spent his working life with Everton, and most of it at Bellefield.

In his youth he worked on the ground staff at Goodison, before later moving to Bellefield with Sid McGuinness. Dougie got his start at the age of only sixteen through his sister, who at the time worked at the Winslow Pub on Goodison Road. She knew the club secretary who agreed to arrange an interview. He started in 1947, and stayed with the club right up to retirement. As a young Blue he couldn’t believe he would be seeing his heroes like Tommy Lawton and Joe Mercer each day. A handy footballer himself, in later years he would regularly join in practice games, and Colin Harvey famously recalled being terrified as a sixteen-year-old youth player, when faced with this ‘older bloke with a beard’ playing up front for the opposition and terrorising his team mates.

In the 1960s, part of the renovations included the old Bellefield cottage, its origins dating back to the Bates’ ownership. When completed, Dougie moved in. ‘I used to love living at Bellefield. I don’t know whether I drove my wife to distraction, but she seemed happy enough being around football. It was a great place to live because of the footballers who lived close by. It was hard work, especially in the early days throughout the 40s and 50s. We only had a 36 inch mower so a lot of the work was manual. It was a 24-hour job but I didn’t mind because I loved the place so much.’ (16) [Dougie sadly passed away in April 2023 and Sid in 2020.]

Another long-serving member of the Bellefield staff was kit man Jimmy Martin. Prior to his appointment in 1990, he was the Men’s Senior Team coach driver during the halcyon days of the mid-80s. Much loved by the players – although often the victim of their practical jokes, Jimmy made the move to Finch Farm, before retiring after over thirty years loyal service to the Blues in 2023.

In a career that spanned 2004 to 2012, which included 256 appearances and sixty-eight goals, Tim Cahill holds a special place in the hearts of Everton fans, not least for his total commitment on the pitch, his full embracing of the club, and understanding of what it means to be an Evertonian;

“The staff, the players, the fans – all were incredibly welcoming. When you join a club like Everton, it’s not just about the player, its also about the people who muck in, day after day – these sixty-year-old Scousers who’ve worked there for decades. Danny Donachie, Everton’s head of medicinal services, often reminds me that I was like a kid in a sweet shop. Everywhere I went I was starry-eyed.