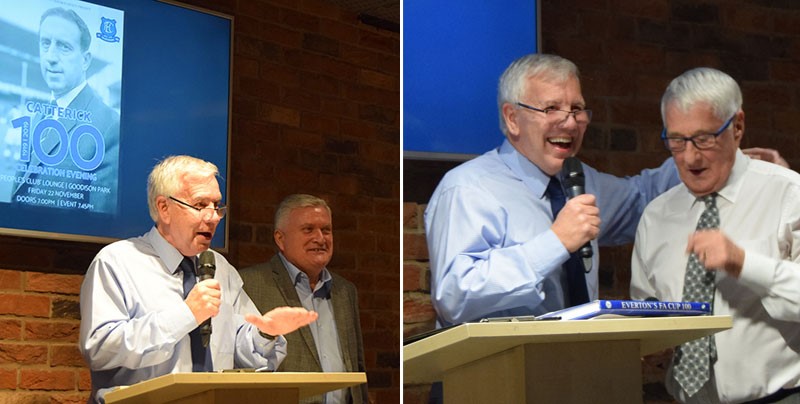

Last Friday, the Everton FC Heritage Society organised and hosted the ‘Catterick 100’ event to celebrate the life and achievements of Harry Catterick – who would have turned 100 on 26th November. He is remembered and celebrated on the Blue half of Merseyside for his stellar managerial achievements in the 1960s. His trophy haul for the Toffees has been eclipsed only by Howard Kendall. Attendees at the celebration event, held in the People’s Club Lounge at Goodison Park, included members of the Catterick family, Heritage Society members, club officials and supporters.

Master of ceremonies, Ken Rogers, led the attendees through Catterick’s life in football, aided by action footage (compiled by Crawford Miles) plus contributions from football historians, former Everton players and Lord Grantchester – grandson of Sir John Moores. Colin Harvey, unable to attend, sent a touching message about his former boss to be read out to an appreciative audience. In the article, below, I summarise the life and times of a true Everton Giant.

________________________________________

Like fellow managerial giant Howard Kendall, Catterick was a son of the North East but moved to Cheshire as a child when his father – also called Harry – signed for Stockport County (he had been spotted excelling for the Chilton Colliery team). Catterick Senior’s association with The Hatters would span 20 years as a player, coach and manager. His son would observe at close quarters the nuts and bolts of football – and learn. Charlie Gee – the Everton and England international centre-half – was responsible for a transfer which would define the Toffees’ future. Coached as a youngster by Catterick Senior, Gee returned the favour by tipping off his employer to the potential of the seventeen year-old Cheadle Heath Nomads’ centre-forward. According to Catterick, Gee ‘painted golden pictures of life at Goodison Park’ to the family. Part-time professional forms were duly signed with the teenager also continuing his apprenticeship (at his father’s insistence) at a marine engine factory.

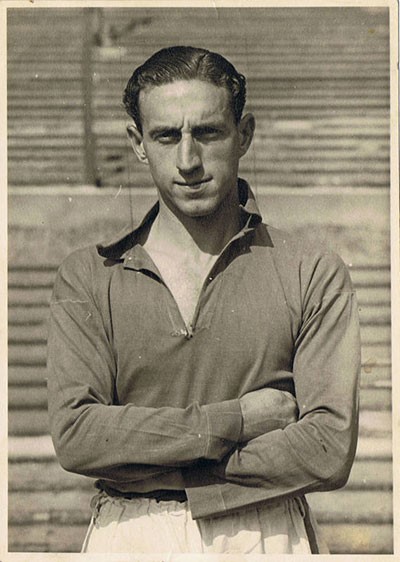

Catterick would train alongside forwards of the calibre of Billy ‘Dixie’ Dean, Tommy Lawton and Robert ‘Bunny’ Bell. When asked to compare Dean and Lawton, some years later, he said: ‘As an overall player Lawton may have been a bit better, but when it came to heading Deany was the best.’ The departure of Dean and the outbreak of war moved the youngster up the pecking order. In wartime matches he’d amass 153 goals in 193 matches for Everton and Stockport (for whom he guested).

When peacetime football competitions resumed, Catterick was installed as the man to spearhead the Blues attack in place of the departed Tommy Lawton. His debut was a 1946 FA Cup defeat to a Preston North End team featuring his future Merseyside managerial rival Bill Shankly. The Football League programme resumed a few months later, but just three matches in, Catterick broke his arm – and did so again soon after recovering. Everton brought in ‘Jock Dodds and thereafter it was an uphill task for the Stockport-based man to win back his place.

Perhaps his finest moment, a hat-trick away to against Fulham in October 1950 was missed by manager Cliff Britton as he was absent, scouting another player. Nonetheless Catterick managed to score 24 goals in 71 appearances for the Blues wearing the famous number nine shirt. For a man who was adept at trading players on as a manager, it’s interesting to note that Catterick – the player – stood his ground when Everton tried to transfer him to Nottingham Forest and Stoke City. However, he bowed to the inevitable in late 1951 after Dave Hickson took his place at centre-forward.

The veteran took his steps first on the managerial ladder at Crewe Alexandra (as a player-manager). From there he moved to Rochdale and did well enough to earn a tilt at the manager’s job at Sheffield Wednesday in 1958. His impact in South Yorkshire was dramatic. The Owls were promoted to the topflight at the first attempt, reached the FA Cup semi-final the following season and then pushed a great Tottenham Hotspur side all the way in the race for the 1960/61 League Championship.

However, the relationship between the manager and his directors was strained (with a difference of opinion on whether player recruitment or stadium investment should be prioritised) and rumours swirled of Catterick seeking pastures new. John Moores, observing from Merseyside, was impressed enough with the Everton old boy to jettison Johnny Carey and bring Catterick ‘home’. The incoming manager had a clear brief from Moores: turn an expensively-assembled but erratic Everton team into title winners – or follow Carey through the exit door.

Under this intense pressure from the directorate and success-starved supporters, Catterick set to work on adding steel and discipline to a talented and entertaining side. Dennis Stevens and Gordon West were first through the entry door, the former hastening the departure of terrace idol Bobby Collins – a sign that Harry would not shy away from making bold, unpopular, decisions. Rebellious Roy Vernon was given the responsibility of captaincy as a concerted push for glory was made in the 1962/63 season.

During the hiatus caused by the Big Freeze hiatus – with late-season fixture pile-up inevitability – Catterick swooped for wing-half Tony Kay and winger, Alex Scott to bolster the squad for the run-in. His finely tuned side held off the challenge of Spurs, Burnley and Leicester City to win the title – Vernon’s final-day hat-trick against Fulham sealing it in style. It was the club’s misfortune to be pitted against eventual winners Internazionale in the first round of the European Cup. Although the Blues lost narrowly, Catterick demonstrated his willingness to blood youth when he handed 18-year-old Colin Harvey his debut at the San Siro.

Whilst the team was in a state of transition from the Championship team to a younger, more home-grown version, it reached the 1966 Cup Final. Catterick made one of the tough choices that marks all great managers when he selected the inexperienced and relatively unknown, Mike Trebilcock ahead of Fred Pickering, the injury-troubled star forward. With Everton trailing by two goals to nil, the Cornishman turned things around with a brace before Derek Temple put the icing on the cake to bring the Cup back to L4. For a man known to be self-contained, Catterick’s dash from the touchline at the final whistle to celebrate was a rare public display of raw emotion. His reserved public demeanour was in stark contrast to Liverpool’s Bill Shankly and that, alongside a wariness of the media, has served to place him somewhat unfairly in the Scot’s shadow. Whereas Shankly seemed to live, breath and sleep football, Catterick would try to escape from the cauldron of elite football management by heading to the golf links – or dining with friends where football talk was strictly off the menu.

Weeks after the Cup Final victory, the Blues’ supremo pulled off one of his career-defining transfer coups – beating Leeds United to the capture of World Cup winner Alan Ball from Blackpool (fellow world-class England international, Ray Wilson, had arrived in 1964). The red-haired dynamo would be joined by Preston’s Howard Kendall six months later to complete – with Colin Harvey – the so-called midfield Holy Trinity. Of their developing, near-telepathic, on-pitch relationship he said: ‘This was something we worked on particularly in the indoor area (at Bellefield) with three and five a-sides with the ball going at lightning speeds. I saw games in there that were, to me, unbelievable. They weren’t very big physically, so they had to be quick and skilful to get by – and by God they were!’

Although Catterick had a reputation for cloak and dagger big-money buys, it should not be overlooked that he had operated successfully on a shoestring at his previous clubs. Even at Sheffield Wednesday he had made just one signing as he galvanized the players. At Everton he developed a blueprint to blend a team of players coming up through the ranks with a sprinkling of star buys. To that end, he had Bellefield redeveloped into a state-of-the-art training centre where his plans could be put into practice. Typically leaving the supervision of players’ training to Tom Eggleston, Gordon Watson and, subsequently, Wilf Dixon, Catterick occupied a role more akin to the modern-day Director of Football – setting the direction of the club, devising team tactics and overseeing transfer activity.

His authoritarian – sometimes remote – style did not always garner goodwill among some players. For him, this was the price to be paid for achieving results on the field. When interviewed by the BBC in 1968, he explained: ‘I’m not a popular fellow because I have always felt that if a decision has to be made, I mustn’t consider whether it’s going to be a popular one or not. The fellow who looks for popularity has something wrong (with him).’ His relationship with fans favourite, Alex Young, could be a strained one. Young’s abundant skill and grace – and goals in 1962/63 – were not enough to overcome Catterick’s belief that a more robust foil for Roy Vernon was required (as evidenced by the arrival of Fred Pickering in 1964 – although Young remained at the club for another four years).

When asked in 1978, after stepping down from management, if he had been too hard on his players, he stood by his approach: ‘I’ve always set very simple principles about people who earn wages – they should work hard to get them. I think Johnny Carey was a bit easy on discipline and one or two players, who were outstanding in terms of ability, had run a little wild. It was one of my jobs to straighten them up, which didn’t make me very popular. Any player playing badly but working hard was never in trouble in with me. The player I didn’t like was the fellow who wanted to play about at night and still wasn’t doing his stuff on Saturdays. That fellow I wouldn’t tolerate – and he would “catch it” from me.’

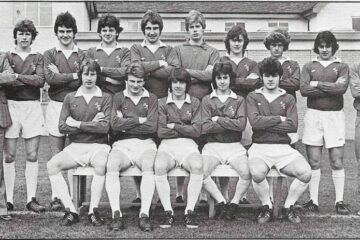

By the late 1960s, the vision of producing an entertaining team based on a fluid 4-3-3 formation was coming to fruition. No less than six players developed through the club’s youth system were regulars in the starting eleven. Ball and Kendall and Colin Harvey may have grabbed the headlines but the manager had crafted a well-balanced side, considered by football purists to be one of the finest seen on English soil. A bullish Catterick stated in 1969: ‘Let’s have this skilful football. If, in producing this highly-skilled stuff, we win a championship, we’ll be delighted. We’re not going to run away from skilful football for heavy grounds – or anything else.’

These words were vindicated when the challenge of great rivals Leeds was seen off as the Blues surged to a seventh League title – sealed on April Fools’ Day, 1970 with goals from Alan Whittle and Colin Harvey. Harvey would look back fondly on that Championship win, and his manager, when interviewed in 1977: ‘I still think about the sheer enjoyment of playing in such a side as the 1969-70 Championship team…Of all the people who impressed me in the game, none did more so than Harry Catterick. I admired his attitude; he always wanted to play what he considered to be the right way. He tried to impress on the players that he wanted to win, but to win properly.’

Then, seemingly inexplicably, things imploded. Fatigued players and injuries to the likes of Brian Labone, John Morrissey and Joe Royle coincided with the loss of the manager’s Midas touch in the transfer market. The surprise sale of Alan Ball in December 1971 – a roll of the dice – proved ill-judged. Under enormous strain, the man in the hot seat suffered a major heart attack early in 1972.

Returning to his duties prematurely, he could not arrest the Blues’ slide. In April 1973 John Moores called time on the Catterick era. A period in a scouting role at Everton was followed by two seasons as Preston manager and a subsequent scouting position for Laurie McMenemy’s Southampton. He remained a regular visitor to Goodison and his great affection for the Toffees was undimmed. In his near life-long association with Everton, Harry Catterick adhered to the club’s motto – for him nothing less than the best would do. No rival manager could equal his points accumulated in the top flight in the 1960s. He set a benchmark for others to follow – including his former players Billy Bingham, Joe Royle, Colin Harvey and Howard Kendall. He enjoyed watching the club’s resurgence under the latter and was in the Main Stand when Everton met Ipswich Town in the FA Cup in March 1985. As the final whistle approached, the 65 year-old suffered a fatal heart-attack – like Dixie Dean five years before him. Later that year, a memorial service was held in his honour at St Luke’s Church – a fitting tribute to one of the most influential and successful figures in the history of our great club.

Rob Sawyer is the author of Harry Catterick: The Untold Story of a Football Great (published by de Coubertin Books). An abridged version of this article appeared in the Everton matchday programme on 23 November 2019.