The First World War had been raging for over a year when the funeral cortege of 17-year-old Robert Goldie brought the small Ayrshire town of Hurlford to a halt. Born in Liverpool, he was the son of well-known local man who had once played football for Everton.

The First World War had been raging for over a year when the funeral cortege of 17-year-old Robert Goldie brought the small Ayrshire town of Hurlford to a halt. Born in Liverpool, he was the son of well-known local man who had once played football for Everton.

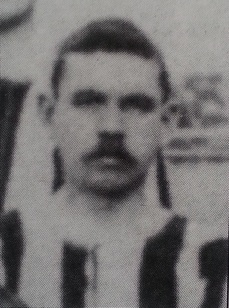

Hugh Goldie, Robert’s father, was born 10 February 1874 at 32 The Vennal in the Ayrshire town of Dalry where his own father, Hugh, worked as a coal miner, while his mother, Janet, had worked in a textile mill. The family later moved to the Riccarton area of Kilmarnock where Hugh, after completing his education, began work in a bonded warehouse while playing football for a local club, Hurlford Thistle. He represented them on 13 February 1892 in the Ayrshire Cup Final that was played at Rugby Park, Kilmarnock. Sadly for him, their opponents, Annbank, beat them 3-0. In July of that year Hugh Goldie married local textile worker Grace McGinn and the couple found a home at Mauchline Road in Hurlford, where their first two children, also called Hugh and Grace, were born.

The strong half-back play of Goldie soon caught the eye of a talent scout who acted on behalf of Scottish Division One side St Mirren, and he signed for the Paisley club just before they moved to a new home at Love Street. Goldie took part in the inaugural match at this location where a crowd of 9,000 people watched the home side lose against Celtic, by three goals to two.

In February 1895 he was selected to represent the Scottish League against the Irish League, along with club mate John Patrick. Also in the side were Jack Taylor of Dumbarton and Laurie Bell of Third Lanark. (These three men were also destined to play for Everton.) The match took place in atrocious conditions at the home of the Distillery club at Grosvenor Park in Belfast. The visitors won 4-1. Goldie, who got on the scoresheet, had an outstanding game and this prompted a visiting journalist to make the following remarks:

The greatest game in the visiting half back line was played by that young and promising player, Goldie of St Mirren who revelled in the mud, tackled with great vigour and banged the ball very cleverly to the man in front. The wing he had to meet was exceedingly smart, in fact, there was not a better combination on the field. Goldie has enhanced his reputation 50% and is in the running for further honours. (Glasgow Evening News 4 February 1895.)

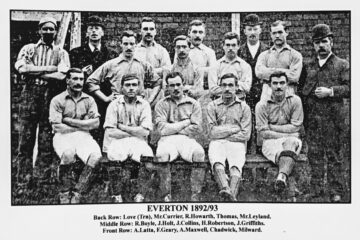

He completed the season with St Mirren, and played in every competitive match, before accepting an offer to move to England and turn professional with Everton. On arriving in Liverpool, the Goldie family took up residence at 10 Gilman Street, off Walton Breck Road (facing Anfield. Now demolished during ground extension work).

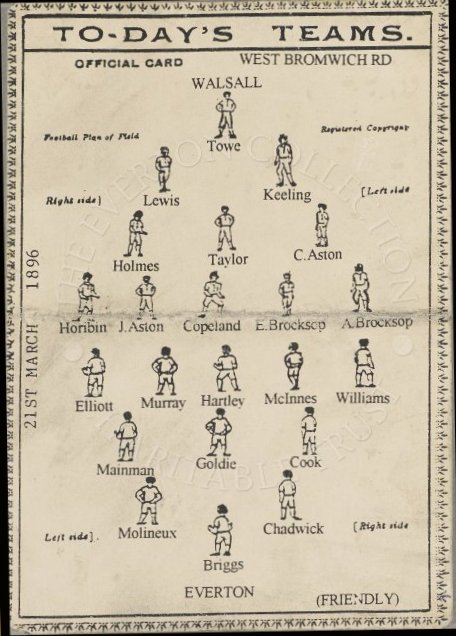

The Scot attended the annual sports day, which that year took place at the Grapes Hotel in Freshfield, where he won the one-mile race, with a handicap of sixty yards. He made his Football League debut, playing at half-back, on 9 September 1895 against a Bury team who had reached the top flight of English football for the first time. Everton won the game 3-2. He made another fifteen appearances, scoring one goal, and accepted the offer to stay for another twelve months. The next season Goldie made only three appearances in the Everton First XI and at the end of the season was put on the transfer list for a fee of £100. In the meantime, while residing at Gilman Street, Grace had given birth on 24 December 1896 to a third child, a boy, who was given the name of Robert.

Hugh Goldie lining up for Everton against Walsall on 21 March 1896

(The Everton Collection)

On 1 May 1897, Hugh Goldie joined Glasgow Celtic and played a big part in them reclaiming the Scottish League championship. He went on to play twenty-seven matches and score one goal for the Parkhead club before being released on 7 January 1899 as part of a cost-cutting exercise. He next played for Dundee, whose home ground was at that time at Carolina Port, where he spent the remainder of the season before returning to England.

On 15 September 1899, Hugh Goldie joined Southern League side Millwall Athletic where he teamed up with former Everton player, Jack Brearley. He played a big part when the Londoners went on an FA Cup run that saw them reach the semi-final and face Southampton. Watched by a crowd of 50,000 people, the game took place at Crystal Palace and it ended in a 0-0 draw. Southampton won the replay, which took place at Reading, by three goals to nil. Goldie went on the make forty-five competitive games for the London side and scored three goals before re-joining Dundee in June 1900. His arrival was noted by a local newspaper:

A couple of seasons ago Goldie played for a while at Carolina Port and at the end of that year Dundee were desirous of obtaining his transfer from Everton. The Liverpool club’s terms were too high and Hugh left for Millwall. However, Everton and Dundee have now come to an understanding in regards to the transfer fee. (Dundee Evening Times, 1 June 1900.)

Hugh Goldie spent two seasons on Tayside before ending his football career, again playing in the Southern League, with New Brompton in 1903.

When the 1911 census was recorded, Hugh and Grace Goldie were the licencees of the Thistle Hotel, Brick Row, Kilmarnock and by then they had eight children. In later life the family settled at 23 Armour Street in Kilmarnock. where he had returned to his job in a bonded warehouse.

When growing up, the male members of Goldie family took a great interest in the game of football, and Robert appeared for Kilmarnock Second XI. He had started work as an apprentice engineer in a local water valves maufacturer, and was there when World War One broke out. Young Robert, despite being only seventeen, enlisted with the 8th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders and was sent to Aldershot for basic training, where he received a bayonet wound. He was admitted to the Cambridge Military Hospital, but sadly, the wound turned septic and, despite efforts to save him, he died of blood poisoning on 19 January 1915. The news of his death shocked the community at Hurlford because he was the first local man to die as a result of the conflict. The body of Robert Goldie was returned to his family and he was given a full military funeral with pipes and drums as well as a full military escort to Kilmarnock Cemetery where he was buried alongside his grandparents. Thousands of people turned out to pay their respects and lined the three-mile route from his home to the graveside. His name may be seen today on the local War Memorial in Kilmarnock. Hugh Goldie lived the rest of his days at 23 Armour Street where he died a year after his wife on 1 September 1935.

Acknowledgements:

Dave Sullivan, author of several books about Millwall FC.

John Stewart, the great-grandson of Hugh Goldie.