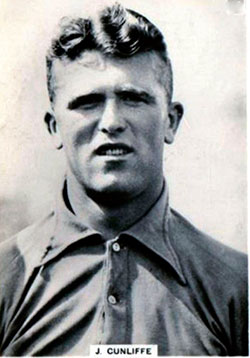

As with many players at Goodison in the 1930s, Jimmy “Nat” Cunliffe’s achievements are overshadowed by the Everton giant that is W.R. Dean. Yet his life in sport was a remarkable one. Plucked from non-league football Jimmy went on to win international honours. Not content with this, he subsequently embarked on enjoy a highly successful career in another sporting arena.

Born James Cunliffe on 5 July 1912 to Mary and Peter (a coal miner), Jimmy grew up in Blackrod – a small settlement close to the current location of Bolton Wanderers’ stadium. Upon leaving school he started an apprenticeship as a plater in the boiler-making section of the nearby Horwich Locomotive Works. The young man excelled at cricket, football and crown green bowls, confiding, years later, to the journalist Stork that most of his friends rated him as a better cricketer than footballer. In one season he had a bowling average of seven but preferred to pursue a career in football, partly as he did not fancy the idea of playing cricket late into the evening. By the age of 17 he was turning out at centre-forward for Adlington FC, having previously played for Horwich.

With Everton suffering relegation from the First Division in the spring of 1930 the board were on the lookout for young talent to restore the clubs fortunes and gain instant promotion back to the top flight. Mr T. Fleetwood scouted Jimmy and teammate R. Parker playing for Adlington in early May. He reported to the board that they were “very promising indeed”. It was left in the hands of the Chairman to conclude a deal for the pair – signing on in early June for £1 per week plus rail fares from their homes – presumably they were part-time pros initially. Adlington FC received the princely sum of £10 by way of a donation from Everton. .

The scouting conducted by the directors that summer was clearly of the highest order as new arrivals, Cliff Britton, Charlie Gee and Jimmy would all represent England whilst at Everton. Jimmy would generally known as “Nat” at Goodison Park – a shortened version of Nathaniel, his middle name. Perhaps this was avoid confusion with the Scottish left-flank duo of Jimmy Dunn and Jimmy Stein.

Jimmy’s chances of selection for the first team were miniscule whilst “Dixie” Dean remained fit and in-form, so he had to content himself with A (third) team and Central League (reserve team) appearances. Come the end of his first season on Merseyside, in which Everton were promoted back to the First Division, he declined the £3 per week on offer for the following season before eventually settling on a revised offer of £4.

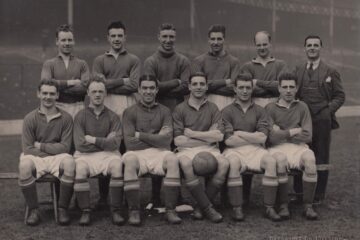

On tour in Tenerife 1934. Jimmy is 5th from left.

On tour in Tenerife 1934. Jimmy is 5th from left.

After three years Jimmy’s first team break finally came when Jimmy Dunn, the inside-forward, was absent through injury. A goal-scoring debut in March 1933 against Aston Villa was over-shadowed by a 2-1 defeat and in the following match, against Middlesbrough, he was described in one press report as “lost from the first minute onwards”. After this second outing Jimmy returned to the reserves until an injury to Dixie Dean in the Autumn presented an opportunity in his favoured central position. He impressed immediately and when Dean returned, Jimmy switched to inside-forward at the expense of “Tosh” Johnson and Jimmy Dunn – chipping in with 9 goals in 28 appearances. From there he never looked back. Proving to be a self-less foil to Dean, contemporary reports noted Jimmy’s speed and ability with both feet coupled with a stinging shot. He contributed 17 goals the next, 1934/35, season but the 1935/36 would prove to be the vintage one. Playing across the front-line Jimmy topped the scoring table with 23 goals – a better ratio than one goal every two games . Twice he hit four goals in a match. In the 5-1 demolition of Stoke City Stork reported:

The game between Everton and Stoke City at Goodison Park was a complete triumph for Cunliffe, the Everton inside left, who scored four of the five goals against the one obtained by the Potters. He was in brilliant form, apart from his goals, for he tripped along with the ball at toe to make clever passes, so that the line moved along smoothly and well. It was, of course, as a goal scorer that he made his big hit, for each of his goals was a magnificent effort, particularly his third, for it was practically a self-made point from start to finish. He beat a number of Stoke defenders before finally coaxing Lewis out of goal and then turning the ball right away and out of reach of the Stoke custodian. I have never seen Cunliffe so sure with his shooting.

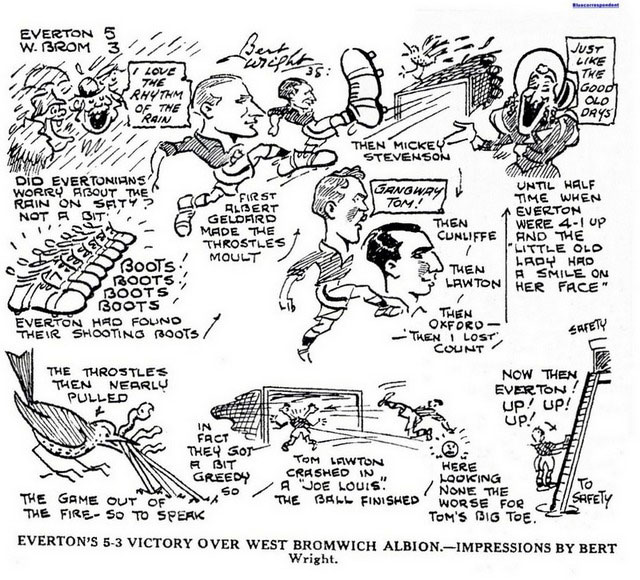

The feat was repeated in a thrilling 5-3 victory over West Bromwich Albion in April. Rewarded with an England call-up he lined-up alongside Ted Sagar in a 3-2 defeat to Belgium in the Stade Du Centenaire (Heysel) Stadium on 9 May 1936. Like fellow debutant Bernard Joy of Arsenal (the last amateur to be selected for England) Jimmy was never selected again but he was the reserve on five other occasions. Humbled by the honour, he cherished his England shirt and cap for the rest of his life. Sporting talent clearly flowed in the Cunliffe family’s blood as Jimmy’s cousin, Arthur, earned two England caps at outside-left in 1932.

Everton 5-3 West Brom, April 1936

Everton 5-3 West Brom, April 1936

Jimmy, unlike most Everton teammates, chose not to live near to Goodison Park – preferring to live in Blackrod for his entire life. His love for the place is confirmed by a post-card he wrote to his girlfriend Margaret Ainscough from Switzerland whilst on a club tour in the mid-1930s:

“This is a very decent place and we are enjoying ourselves very much considering we are so many miles away from home, but there is no place like good old Blackrod.”

Jimmy remained a near-automatic pick at Everton for two further seasons but, sadly for him, his greatest Everton days coincided with a fallow period as far as silverware was concerned. He picked up an ankle injury in the Empire Exhibition Trophy Final, held in Glasgow in June 1938. This required an operation to remove four bone splinters and probably robbed him of some his lightning-fast pace. When deemed fit again in the autumn, he found himself unable to displace the less skilled but more defensively industrious Stan Bentham from the team. Instead he gave yeoman service in the reserve side alongside the likes of Cliff Britton, Charlie Gee and Bob Bell. When called up to the first team in the 1938/39 season he scored three goals in seven appearances –– sadly this was not enough to qualify for a medal when the league crown was secured.

Jimmy was retained by Everton for the 1939/40 season but, when this was abandoned after only three games his playing contract was terminated (his registration was retained by the club). As a gentle soul Jimmy would countenance inflicting death and injury on the wartime enemy so he served down the pits in the Lancashire coalfields. Everton gave him permission to “guest” for his nearest league club – Bolton Wanderers in the first two wartime league seasons, after which he became a regular guest for Rochdale, maintaining an impressive strike-rate. His sole wartime Everton appearances would come early in the 1941/42 season but, alongside other stalwart Evertonians, he was rewarded with a long-service “benefit” cheque for £520, presented at Goodison Park in April 1944.

When peacetime football resumed Jimmy, was released by Everton in September 1946 and played in two Third Division North fixtures for Rochdale before retiring from professional football. Shortly afterwards, in the summer of 1947, he finally married Margaret after in excess of a decade of courtship – they would have one child together, James (commonly known as Jimmy or Jim) in 1953.

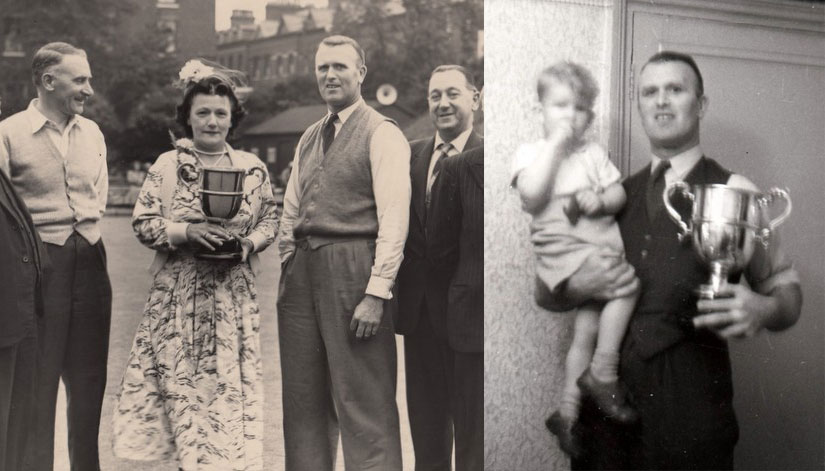

Jimmy’s career came full circle when he was employed again at the Horwich Locomotive Works, labouring in the spring smithy section. However, another sporting career was dawning. Jimmy had continued to play amateur play bowls throughout the 1930s and 1940s, he was a frequent finalist in competitions sponsored by the News of The World and in 1955 won the coveted Sarti Cup – he was pictured cradling the trophy in one arm and his young son in the other. In 1958 he swapped his factory job for The Panel, the name given to a select band of professional crown green bowls players who would compete on up to six evenings per week across Lancashire. Panel Bowling, as it was known, was popular in the area with considerable sums wagered on the outcomes by 200-plus spectators. The players (generally, between four and eight were on The Panel) could earn over £1000 per year in appearance fees and prize money (£5 for a win, £4 for a defeat).

Jimmy Cunliffe with the Sarti Cup, 1955

No quarter was given to the newcomer and Jimmy had to devise a scientific of overcoming his uncompromising opponents. Through studying the contours of the greens and favouring bowls with a high degree of bias (known as “strength”) he was able to position the jack in a location where only his bowls would hold. He had one other advantage over his opponents – physique. In 1963, the journalist Fred Eaton chanced upon Jimmy having a wash between games and noted:

He is 6ft tall and pulls around 14 stone with powerful shoulders and a good deep chest…He looks what he is: an all-his-life athlete. But what impresses me most in the 50-year-old-man is the air of professionalism about him. Here before me is the sort of man that typifies the big-timer in sport.

Another journalist, Michael Hardcastle, observed Jimmy in his element on the green and noted, amongst other things how the ankle injury sustained in at Hampden Park back in 1938 continued to trouble him:

Cunliffe is the master tactician, the hardest man in the game to beat on his day and his favourite greens. As he follows a wood to the jack he is expressionless, unruffled. He wears flannels, olive pullover, flat cap and walks a little crookedly on an arthritic right ankle.

On holiday in Blackpool in the mid-1950s

By the mid-1960s Jimmy had become the pre-eminent bowls player thanks to his talent, preparation and fitness. There was even talk of making all players use the same standard strength of woods in order to temper his advantage.

Edgar Boardman, a neighbour, recalls Jimmy being interviewed on television about his bowls career. In a strong Lancastrian dialect he told the interviewer: “Tha always knows when tha’s bowlt a good wood – tha can tell as soon as it’s left the ‘and”.

In spite of the relative riches earned as a Panel Bowls player he lived modestly. After collecting his winnings (in cash), Jimmy would get the bus home after the match each evening. He didn’t own a car, stating that he “never fancied one”

By the early 1970’s, Jimmy was stepping back from professional bowls but The Panel continues to this day at the Red Lion in West Houghton.

Although no longer involved in football Jimmy would still follow the game and was fortunate enough to attend FA Cup Finals as a spectator at Wembley on a number of occasions. In conversation about football he would sometimes mention that he had once played for Everton alongside Dean et al but he did not labour the point.

Jimmy bowls in a match against Ron Kellett

Jimmy Junior, a roofer by trade, relocated to Torbay on the south coast and it was here, in 1983, that Jimmy’s grandson – another James – was born. Jimmy and Margaret would journey down from Lancashire to visit the young family. Their daughter-in-law, Sheila, recalls Jimmy being was a lovely, quiet man – happy to leave Margaret to do the lion’s share of the talking. He passed away in hospital on 26 November 1986, aged 74, following a stroke suffered at home on Chorley Road.

Despite the passing of time since his footballing days, word of Jimmy’s passing, somehow, reached Goodison Park. At the funeral service, the family were surprised, but delighted, to see a blue and white floral tribute sent by Everton Football Club.

In a remarkable parallel, another Blackrod-born centre-forward was plucked from non-league football to join Everton and earn England honours. Frank Wignall was signed by the Blues from Horwich RMI in 1958. Despite an impressive goal return, he failed to impress the incoming Harry Catterick and after one game (and one goal) in the 1962/63 championship season he was transferred to Nottingham Forest where he won two caps for the national team.

Jimmy Cunliffe and Margaret circa 1985

Career Stats:

Everton:

187 League and cup appearances – 76 goals

3 wartime appearances – 1 goal

Bolton Wanderers:

27 appearances – 8 goals (wartime guest)

Rochdale:

119 appearances – 54 goals (wartime guest)

2 Football League appearances – 0 goals

England

1 appearance – 0 goals

Acknowledgements/Thanks:

The Cunliffe family

The Crook family

Rosemary Hill

Edgar Boardman

Keith Dickinson

Sports news articles and images on Blue Correspondent website (Billy Smith)

Everton Encyclopedia – James Corbett

Gwladys’ Street’s Blue Book – David France with Gordon Watson

Everton: The Complete Record – Steve Johnson

Everton Collection (Minute Book transcripts)

Family/bowling photos are used care/of Jimmy’s relatives