Dr David France OBE (Founder of Everton FC Heritage Society and Life President)

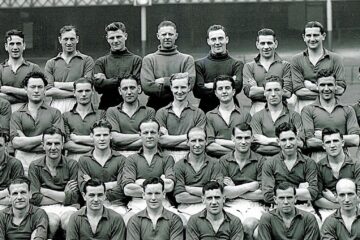

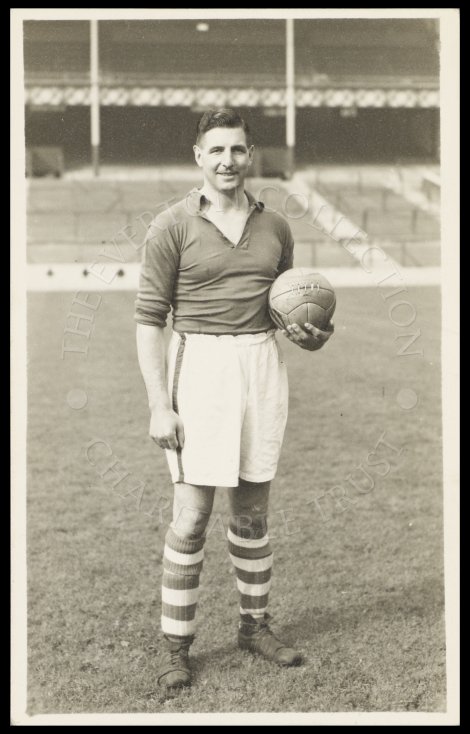

(Gordon Watson back row, third from right. Photo – The Everton Collection)

Something of a raconteur, Gwladys Street Hall of Famer Gordon Watson loved to share tales of his life at Goodison and he once spoke passionately about his team-mates from the side he regarded as ‘The Forgotten Champions of 1939’

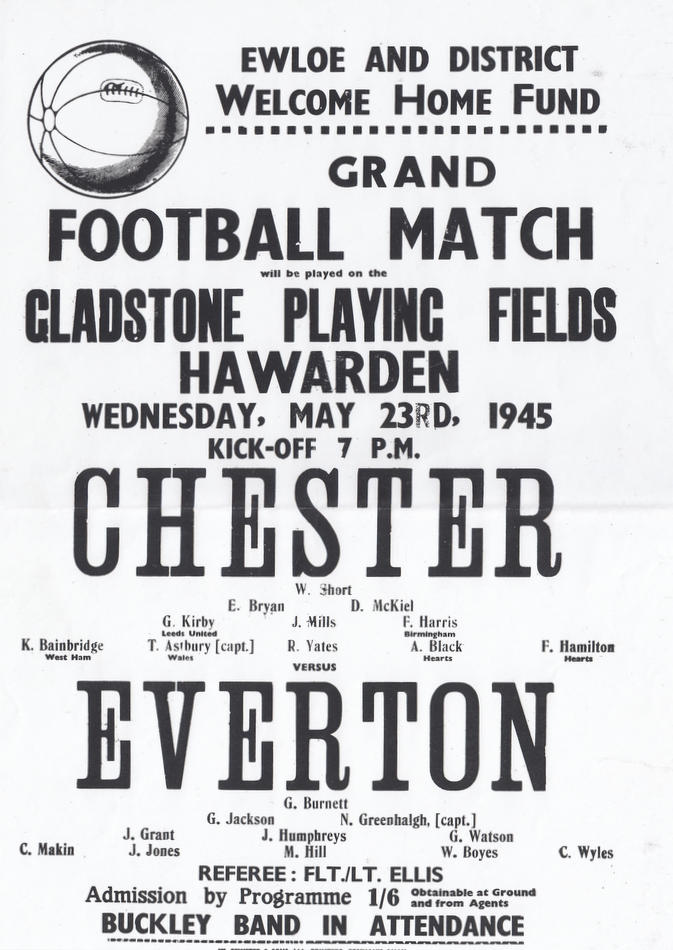

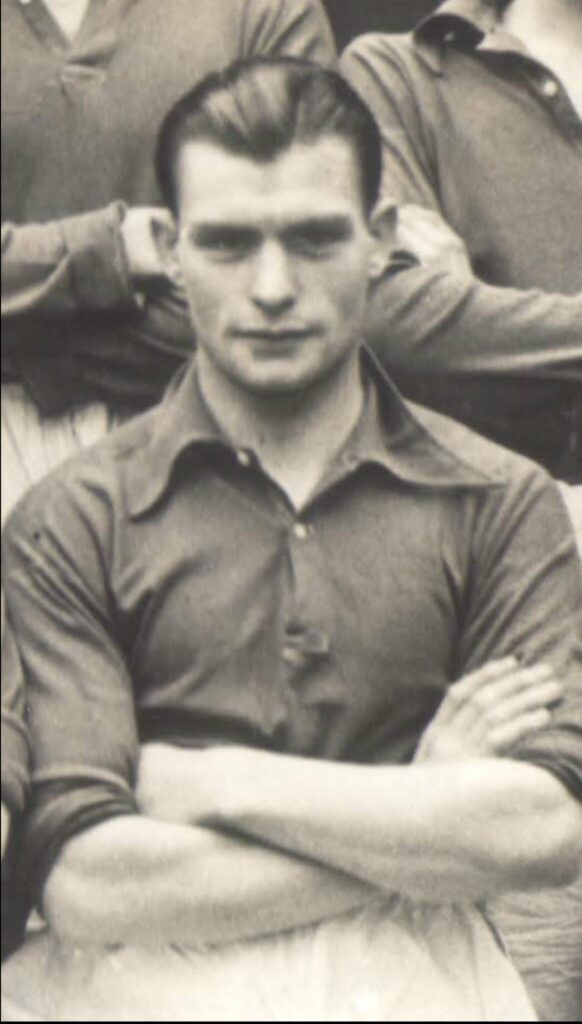

‘Gordon Watson? Never heard of him.’ Well, the Geordie (from the same neck of the woods as Howard Kendall) played alongside Dixie Dean in Everton’s Central League-winning side in 1938, helped Tommy Lawton and Joe Mercer capture the First Division title in 1939, made nearly 200 appearances in war-time football, coached first-teamers like Dave Hickson and Bobby Collins, developed youngsters including Colin Harvey and Joe Royle, before winding down his 64 years at Goodison by working in the club’s promotions department, pulling pints in the matchday lounges (despite being a teetotaler) and serving as stadium tour guide.

A couple of years after Gordon’s retirement from Everton, my dear friend Brian Labone advised me that the club planned to sell the house that it had rented to the wheel-chair bound veteran for almost four decades and evict him and his daughter/carer Hilary. I know, you couldn’t make it up. Subsequently, after my short meeting with the club’s representatives (the individuals involved are no longer at the club and their names are not important) in 1997, Gordon was assured of his tenancy during his lifetime, presented with a mantel clock and invited to the next home game as the guest of chairman Peter Johnson. More recognition was to follow.

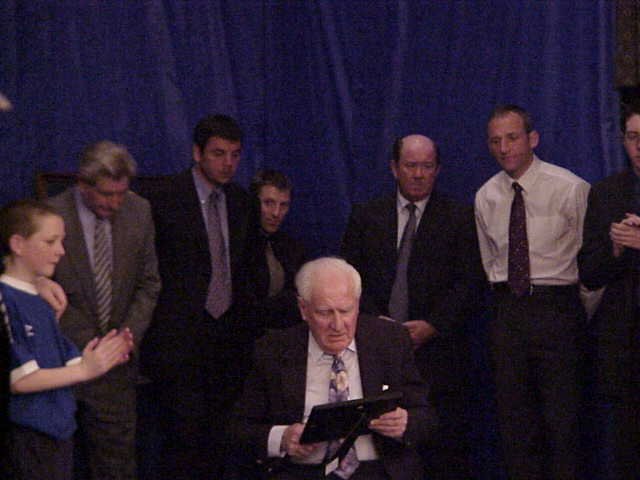

As a result of him spending 16 years as a player and 21 years as a coach under managers Cliff Britton, Johnny Carey and Harry Catterick, Gordon Watson was voted into Gwladys Street’s Hall of Fame alongside Paul Bracewell and Andy King in 1999. After being carried onto the Adelphi stage by Dave Watson, he promised to return the following year pain-free and without his wheel-chair. True to his word, after all 750 booted-and-suited guests had been seated, Gordon marched into the banquet hall in 2000 carrying the FA Cup above his head to a memorable reception of cheers and tears.

How so? Well, I visited Gordon during my frequent trips from North America throughout 1998 and 1999 and, given that he was considered too old for NHS support, embraced him as the first old Blue to receive medical treatment from the newly established Everton Former-Players’ Foundation. Previously, we had helped Gordon West find his feet, but that is a story for another time. The challenges associated with the 80-odd year old’s hip replacement procedure were significant – he had no ball in his ball-and-socket joint – just jagged bone. Working with Gordon Taylor at the PFA, we helped him to walk again.

During his rehab, Gordon received regular visits from his former teammates, disciples and admirers. Something of a raconteur, he loved to share tales of his life at Goodison – the triumphs, the silverware, the defeats, the relegation woes and, of course, his eye-opening memories of Dixie Dean, Jock Dodds, Harry Catterick, Theo Kelly, Will Cuff, John Moores, etc. Some were documented in Gwladys Street’s Blue Book (published in 2002), others will remain confidential.

A lovely man, Gordon made 16 League appearances when Everton captured the title and believed that ‘The Forgotten Champions of 1939’ were as good as Howard’s men in 1984, but trailed a little behind Harry’s team of 1970 side. Remember the only three-man team to be crowned champions? In fact, he claimed that his 1939 teammates would have dominated English football for a few seasons if Germany had not invaded Poland but considered them forgotten by younger Evertonians and other football fans. Gordon noted: ‘Football moves on. It always has and no doubt always will. After our enforced absence which lasted seven First Division seasons, our big stars had departed and our line-up contained only Ted Sagar, Norman Greenhalgh, TG Jones, Wally Boyes, Alex Stevenson and yours truly from the championship side – and none of us were spring chickens. Memories of our 1939 success have been quashed by the war-time sacrifice and post-war austerity.’ While wading through his collection of team photographs he spoke passionately about all members of the Forgotten Champions. As always, I kept detailed notes …

Ted Sagar: ‘All goalies are nutters and the Yorkshire miner was no exception when took up his position between the posts. As the commander of his penalty area, ‘The Boss’ would bark instructions at his defenders who were forbidden to make passes towards him. Not as tall or as agile as the typical Premiership Goliath, he was extremely brave and untroubled by combative shoulder charges. In fact, Ted was an expert at plucking crosses out of the air. Predictably, his performances declined as he got older which wasn’t surprising since he played until he was 50 (actually 41 years and 82 days). For most of his career, Ted wore the same green woolen sweater which was darned monthly by my wife Olive. I think he had only new six jerseys during his entire career.’

Billy Cook: ‘The right-back was a confident footballer with good ball control and was one of most battle-hardened members of our team. His reputation for being volatile with a short fuse preceded him and intimidated opponents as well as some of own team-mates. As his room-mate, I went out of my way not to upset him. The Irishman had made a name for himself at Celtic as well as at the Winslow Hotel. Guinness was his favourite beverage and its impact had many late-night curtains twitching in Goodison Avenue. After one infamous domestic dispute, he was ‘taught a lesson’ by Bill Dean and Tommy White. I can’t recall why, but he took over 12-yard duties from Tommy Lawton and, even though he missed his first effort, no-one was brave enough to take the ball off him, went on to net five prefect spot-kicks. ’

Norman Greenhalgh. ‘We nicknamed him ‘Rollicker’ – behind his back. Like other people from Bolton (namely Alan Ball), his ‘words of encouragement’ were as fierce as his tackles. The left-back served as Wally Boyes’s minder and opponents bruised the Everton winger at their own peril. Norman was an uncomplicated footballer who matured quickly to represent England in a wartime international fixture just two years after the joining us from non-League football. Very few opponents got past him. Stanley Matthews hated playing against him and allegedly claimed that he would boot wingers into the air and wait patiently until they had landed before kicking them again. Of course that’s an exaggeration but, by his own admission, Norman did like to ‘squash’ them to prevent crosses into Ted’s box.

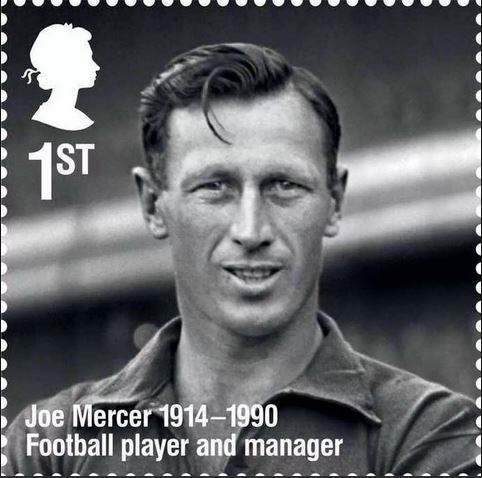

Joe Mercer: ‘One of the most charming gentlemen I have ever met inside and outside of football. The versatile wing-half made the game look so easy. Respected as the rising star of English football, he was one of our most influential team leaders – of which we had a few. Since trainer Harry Cook was essentially the keeper of the magic sponge, it was left to Joe, former-captain Billy Cook and captain Jock Thomson to make decisions about tactics. It was something that they were good at. Everyone liked Joe – except Theo Kelly. Following a post-war row with the club secretary turned manager, the life-long Blue bolted to Arsenal where he won two more League titles and another FA Cup. His wife Norah was so proud of his accomplishments that she wore his medals on a bracelet. Even though he was voted Footballer of the Year (in 1950), Joe and Norah ran a modest grocery shop in Wallasey. Can you imagine the current Footballer of the Year (Eric Cantona) even visiting a corner shop? The departures of Joe and Tommy Lawton to London sent Everton into a post-war decline.’

Tom G Jones. ‘In my eyes, TG was a more polished defender than Bobby Moore. If he had been English and played for a London club, he would be a household name. Cultured, cool and composed, and don’t forget confident, the young centre-half liked to dribble the ball out of his own box – much to the delight of the fans and the annoyance of Ted Sagar. Back then, the typical centre-half was all brawn – so Tom was a revelation who mastered adversaries with firm yet fair tackles, shrewd positional sense and uncanny anticipation. Having won the ball, he could stroke it with no little elegance to a well-placed team-mate. Some admirers called him the ‘The Prince of Centre-Halves’ whereas I christened him ‘Cryogenic Jones’. He had just turned 21 during our League-winning season and the outbreak of the Second World War impacted his advancement more than most. After falling out of love with Everton, he left Merseyside in late-1949 to manage a semi-pro club as well as a hotel in Pwllheli, North Wales.’

Jock Thomson: ‘We all respected Captain Jock who never failed to inspire those around him. He had done it all at Everton – relegation, promotion, First Division champions twice and FA Cup winner. Whereas he played in only one fixture for Scotland– unfortunately, he put through his own goal against Wales and was never picked again. The left-half was a powerhouse similar in style to Ron Flowers (Wolves) and Dave McKay (Hearts and Spurs) who was not afraid to use his physique to his advantage. Though he wasn’t a bully, Merseyside folklore claims that he made one particular challenge on Brentford’s Dai Hopkins, during my first-team debut in early-1937, shook the earth around Griffin Park. Jock was dogged by injury during his last few seasons at Everton and, as a result of his absence, I was promoted from twelfth man/travelling reserve – remember there were no substitutes back then – to the first-team. Upon retiring, Jock turned to coaching and managed Manchester City for a while.’

Torry Gillick: ‘As a rule, every League-winning side had a Scotsman in its ranks. We were lucky because we had two. Equally as effective on either flank, Torry was a touchline winger who was not expected, nor encouraged, to defend. He was fast – but not an out and out sprinter like Albert Geldard, and goal savvy – similar to Alex Scott and Andrei Kanchelskis. Typically, he would knock the ball past his marker, explode to catch it up and dribble with it under his complete control before crossing or cutting inside towards goal. Like all wingers, he was subjected to heavy tackles, and played with more than niggling injuries because he was fearful of losing his first-team place. Harry Cooke would strap his ankles and rub his infamous mixture of iodine and fag ash on the injured area. We became life-long friends and worked together at Harland & Wolff shipyards in Bootle after the start of the war. Sadly, my best pal never recovered from the severe burns to his hands and face when his garage in Aintree caught fire in late-1939 and he returned to Rangers. Within no time, he became a successful scrap merchant in Glasgow.’

Stan Bentham: ‘No doubt because we worked together for almost 30 years, Stan and I had much in common. Like me, he was signed from the obscurity of non-League football (Wigan Athletic), his first-team days spanned the war and included 200 war-time appearances and worked behind the scenes as a coach for donkey’s years. And like me, he was a baseball enthusiast. Also we worked together at Harland & Wolff shipyards during the war. At Goodison, Stan was an unsung footballer – similar in style to Dennis Stevens who toiled diligently in midfield without fanfare or praise. The inside-right was relentless in his efforts to win the ball and was constructive in possession – usually passing it to his right-winger who then won the applause of the crowd.’

Alex Stevenson: ‘The Irishman was a football virtuoso and entertainer. In my humble opinion, he was one of the best ball-players of his era. At 5 feet 3 inches tall, Alex was often targeted by opponents and credit should be given to Jock Thomson who protected him. The inside-forward’s criss-crossing with his left wing partner ran defenders ragged and delighted the Goodison faithful. In addition, he scored some key League goals – netting 10 times during our glory season (for the record, Torry Gillick scored 14 goals and Stan Bentham added another 9). Alex was a Goodison favourite. He adored Everton and the crowd was happy to return his love. Despite serving in the RAF, he helped Norman, Stan, TG, yours truly and Theo Kelly keep Everton ticking during the war years.’

Wally Boyes: ‘The left-winger was another midget at 5 feet 3 inches on his tip-toes. The England international had been recruited from West Brom for a tidy transfer fee (£6,000) during the previous season to fill the void created by Jackie Coulter’s horrific injury. Immediately, he formed a tremendous understanding with Alex Stevenson. ‘Curly’ was an expert dribbler and appeared unhampered by the fact that he had one peg much shorter than the other. His job was simple – to get to the by-line and cross with accuracy to towards Tommy Lawton. Nothing else was asked of him. The winger netted infrequently (4 League goals during the title-winning season) but again that wasn’t his job. However, I must admit to growing tired of hearing about the 17 goals, or was it 18, he scored in one game as a schoolboy.’

Tommy Lawton: ‘With Bill Dean in decline, the lad from Farnworth was a breath of fresh air. The teenage centre-forward was fast, two-footed and headed the ball with Dean-like power and accuracy. Even though he lived in the shadow of Dixie, he was prolific and scored goals for fun. So much so that Tommy topped the First Division’s chart with 28 in the 1937/38 season and again with 34 in the 1938/39 season. While he didn’t come close to Dixie’s 60, his statistics for Everton and England are incredible. (Peace time – 70 goals in 95 league and cup games for Everton, 21 goals in 23 appearances for England. Wartime – 152 goals in 113 games for Everton, 24 goals in 23 appearances for England). Tom was only 19 and perhaps a little cocky when we won the League title. (Agnes Ireland, my mother-in-law, went to school with him in Bolton and remembered him as a ‘big head’.) More than any other top footballer, his career was impacted by the outbreak of war. Apparently, his life turned sour after he left Everton. I was disturbed to read of his much publicized family woes, financial troubles, spells of unemployment and skirmishes with the law. An early case of too much, too soon? Nonetheless, I was impressed that Everton – thanks mainly to Joe Mercer – organized a testimonial match to pay off his debts in 1972.’

Gordon continued, ‘Football has been good to me. I have met some wonderful people. I have memories that nobody can take away. As a player, a coach and a fan, I have seen some terrific players in the royal blue of Everton.’

‘Here is my all-star XI …’

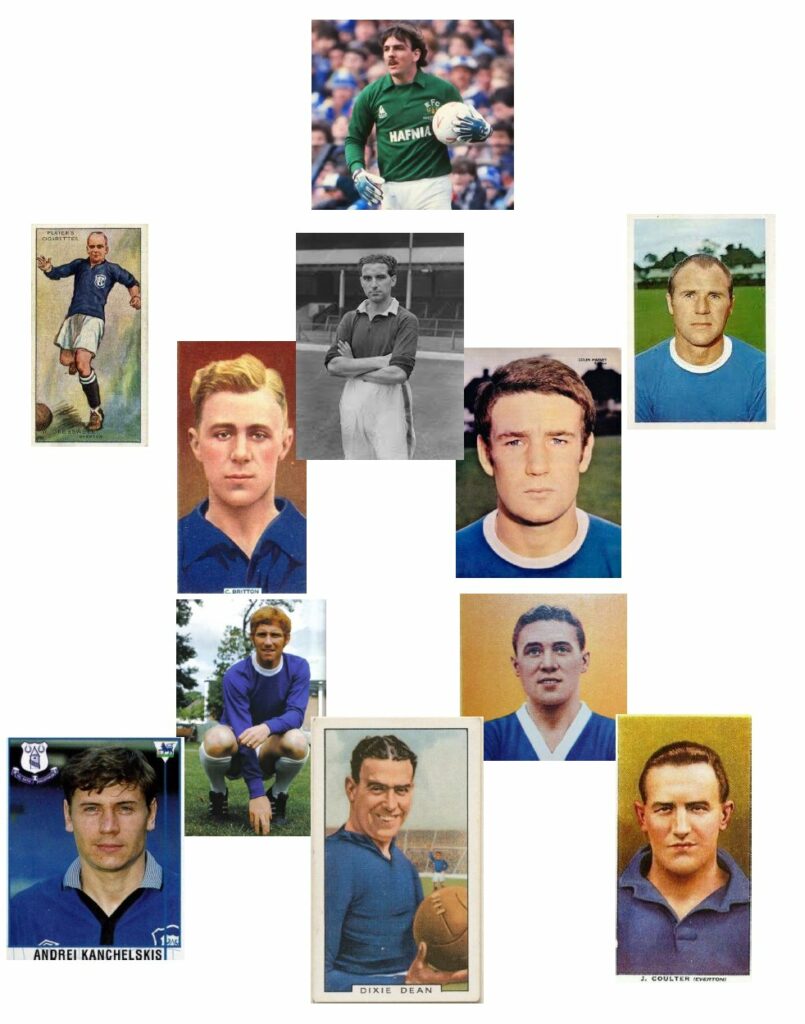

‘Neville Southall was simply the best. Every good team has a great goalie and Howard Kendall signed the best shot-stopper in the world. The Welshman’s contributions were immense. In my eyes, he was more reliable than Gordon Banks and Pat Jennings. Of course, he was a little odd – but I admired the fact that he was a teetotaler. Like many others, he stayed a little too long and lost his spring but never lost his pursuit for clean-sheets. Few world-class players have turned out for the club in my life-time. The others are Ray Wilson, Tommy Jones, Joe Mercer, Andrie Kanchelskis, Dixie Dean and possibly Alan Ball. (NB – Gordon died in April 2001, 15 months before Wayne Rooney made his senior debut against Tottenham Hotspur.)’

‘Coincidentally, both of my full-backs joined Everton in their twilight years and both smoked Ogden’s St Bruno tobacco in their wooden pipes. Warney Cresswell was an intelligent and elegant defender possessing unlimited self-assurance, whereas Ray Wilson was simply world-class. There aren’t enough adjectives to describe him. The lives of international footballers were different in the Sixties. For example, Alex Young worked down the pit on the day before turning out for Scotland at Hampden and Ray helped his father-in-law (an undertaker) embalm bodies the day after playing for England at Wembley.’

‘I have selected Cliff Britton over Joe Mercer at right-half. Cliff was considered by many to be the finest passer of the ball in the English game. I wasn’t too shabby in that department and, after training at Goodison; we would exchange 30-yard passes for an extra half-hour. Cliff made the same sweet noise as Arnold Palmer striking a golf ball. He was an excellent instructor and I adopted one of his routines. In the Sixties, all of our raw apprentices had represented either Liverpool, Lancashire or England schoolboys. Many were brash and far from impressed by the look of a 50-odd year old coach in an old grey tracksuit. Following Cliff’s example, I would instruct each of them to place a ball in the centre-circle at Bellefield and retreat to the touchlines. Next, I would clip the balls to their feet with pin-point accuracy, then ask them to return the balls to the centre-circle and repeat the exercise. They looked bewildered as I tottered away after telling them ‘when you can do that, you can call yourself a professional footballer.’ Though an excellent playmaker, Cliff was an unpopular manager. Despite taking us down to the Second Division, he sued the club and allegedly demanded his club house as compensation.’

‘My No 5 is TG Jones. As you know, I considered him to be a world-class defender. However in retirement, I found Tom to be bitter old man who didn’t have a good word to say about Everton Football Club. Clearly, he never forgave it for preventing his move to Roma or dismissing his application for a coaching job in the Fifties. Moving on. Colin Harvey was the finest young footballer that I ever coached. Tongue-in-cheek, I tell everyone that I taught him how to master the ball. ‘Snarler’ was the complete midfielder – more combative and more skillful than Alan and Howard. While he was not confident in front of goal, he scored two crackers – the winner in the FA Cup semi-final against United at Burnden in 1966 and the League title clincher against West Brom at Goodison in 1970.’

‘On to the 5-man forward line in my 2-3-5 line-up: Andrei Kanchelskis is my preference on the right-wing. What a player. Fast and direct, he was a full-back’s nightmare. Whenever he received the ball, Goodison rose to its feet and held its collective breath. At inside-right, Alan Ball was an enlightened signing by Harry Catterick. A bargain. His perpetual motion changed our British football’s yardstick for midfielders. Alan possessed the finest first-touch of any player at Bellefield. Also he was a winner and demanded high standards of others even when he was not playing well himself. As for Harry’s decision to sell him? Emotion aside, Alan was no longer as influential and his goals had dried up, but I don’t know how the manager expected to replace the ginger one. My other inside forward is Bobby Collins. His arrival revitalized the club. Only 5 feet 2 inches tall, he was a giant in size 3 boots. Hard and feisty, Bobby dominated games with his vision, skills and tackles and ruled the dressing room with his words. But after a heated exchange with Mr Moores, Harry seized the opportunity to off-load him. It was the worst decision that the boss ever made, far worse than selling Alan Ball. Bobby went on to excel at Leeds and was voted Footballer of the Year in 1965.’

‘And at outside-left? I don’t hesitate to pick Jackie Coulter. Despite or possibly because of his massive plates of meat (feet), he was the best dribbler of his era and a wonderful entertainer. During one purple patch in early-1935, he ripped defences to shreds. He was simply unplayable. Then two months later, he broke his tibia on international duty for Ireland against Wales. Although Jackie returned to first-team action, ‘The Jazz Winger’ was never the same player.’

‘Finally, with due respect to Alex Young and Tommy Lawton, my choice of spearhead has to be Bill Dean. Single-handedly, Dixie reinforced our standing as a leading club worldwide. I respect Tom Jones’s claims that Tommy Lawton was a better all-round footballer but Bill was a football god. I feel privileged to have played two games alongside him in the first-team and dozens more in the second-team. With Dixie leading the attack, it was no surprise that won the Central League in 1938. Though he was no longer at his peak and not in the best nick, everyone at Everton was in awe of him. If he congratulated me on a good performance or even a good pass, it made me feel 10 feet tall. It was like being blessed by The Almighty. I have never understood why the club did not engage him as an ambassador after the war. Like me, Dixie loved Everton and its supporters.’

Gordon Watson – a gentleman, a forgotten champion and one of us.

……………………………………………………………….

Further reading

David France and David Prentice, Gwladys Street’s Blue Book (2002)

Rob Sawyer, The Prince of Centre-Halves – Life of Tommy ‘T.G.’ Jones (2017)

Rob Sawyer, Jack Coulter: From Whiteabbey to Goodison Park (2022)