by Mike Royden

Some years ago, I was working on an extensive project to research and document the history of Ellesmere Port during the First World War, which covered life on the home front, those that served in the forces, and those who sadly did not return. I created a website to share the research and stories, which also covered the recording of the biographies of the servicemen listed on the town’s war memorials.

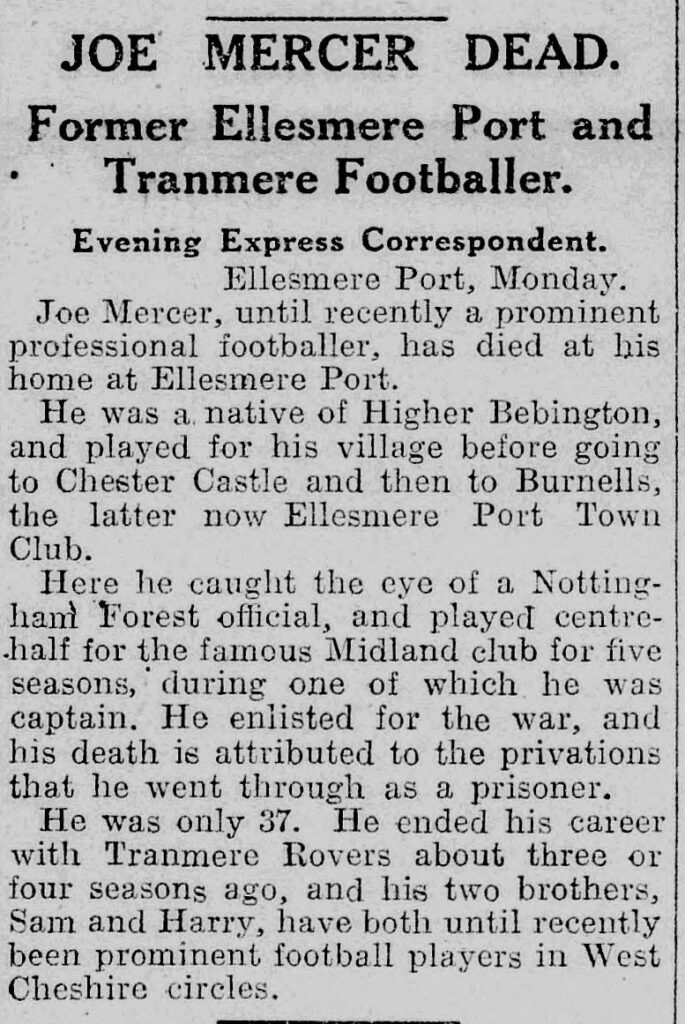

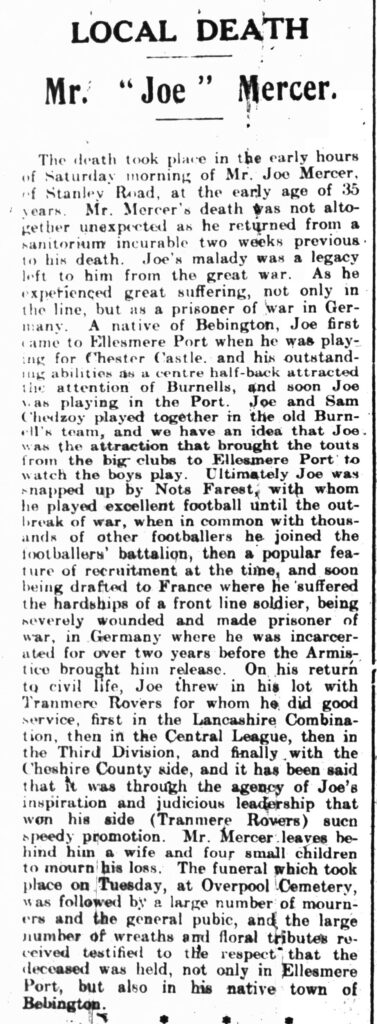

One name sprang out while scouring the newspapers of the time – that of Joe Mercer. It was an interview he gave to a local journalist, in which he described his experiences as a prisoner of war. Of course, as an Evertonian, I was well aware of the career of Joe Mercer, and although too young to have seen him play, I was still old enough to have witnessed his successful managerial career, especially that great Manchester City side of the late sixties. But surely he was too young to have fought in the First World War? Yet, here was Joe Mercer – a professional footballer – coming home after the war to Ellesmere Port, the home town of the Everton icon.

Well of course, the answer was obvious, and after a quick check of the records, it was confirmed that this was Joseph Mercer senior, the father of Joe of that great 1930s Everton side. I had no idea that he too had been a footballer, which initially had me confused. So here is his story, featuring his footballing career, and his horrendous experience of war.

Joseph Mercer senior – Footballer and Soldier of the First World War

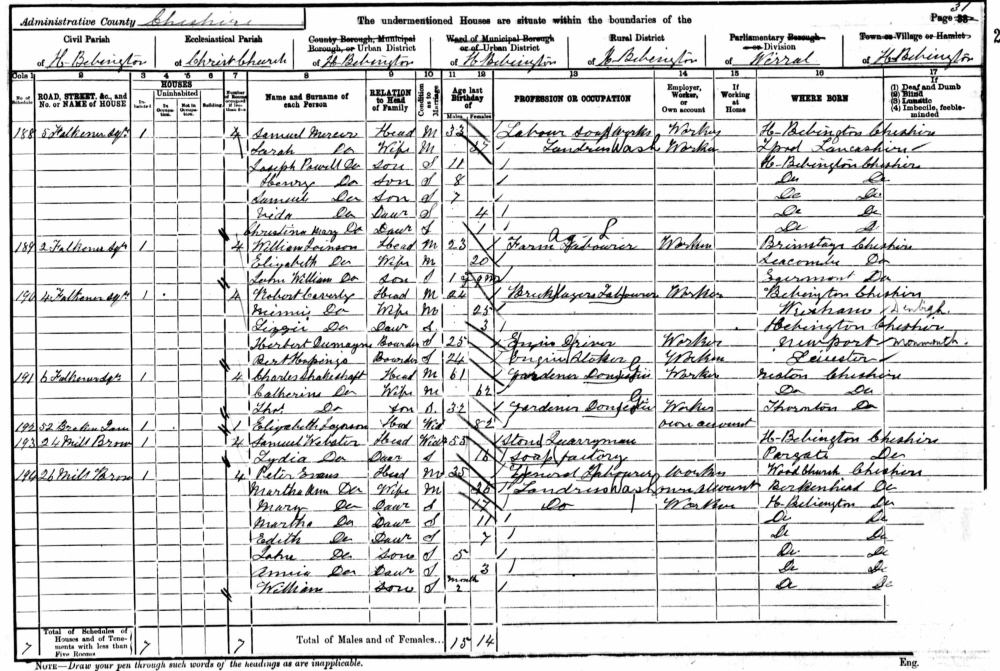

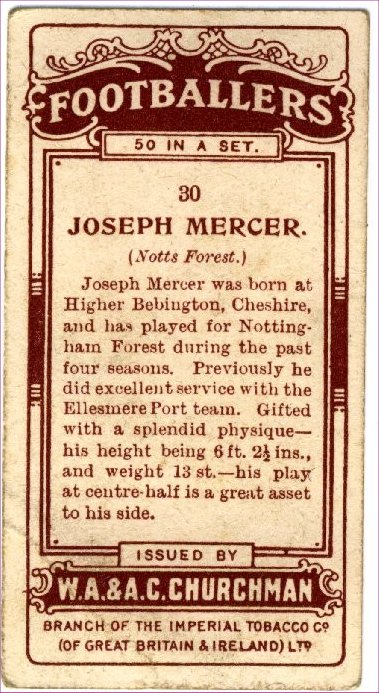

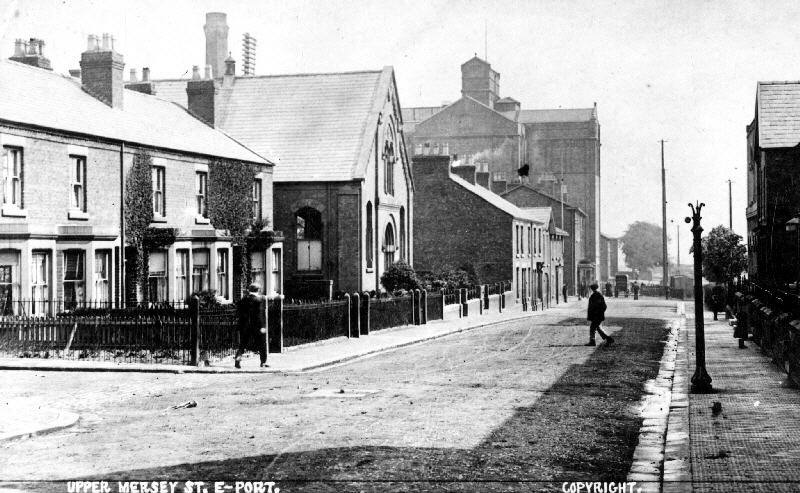

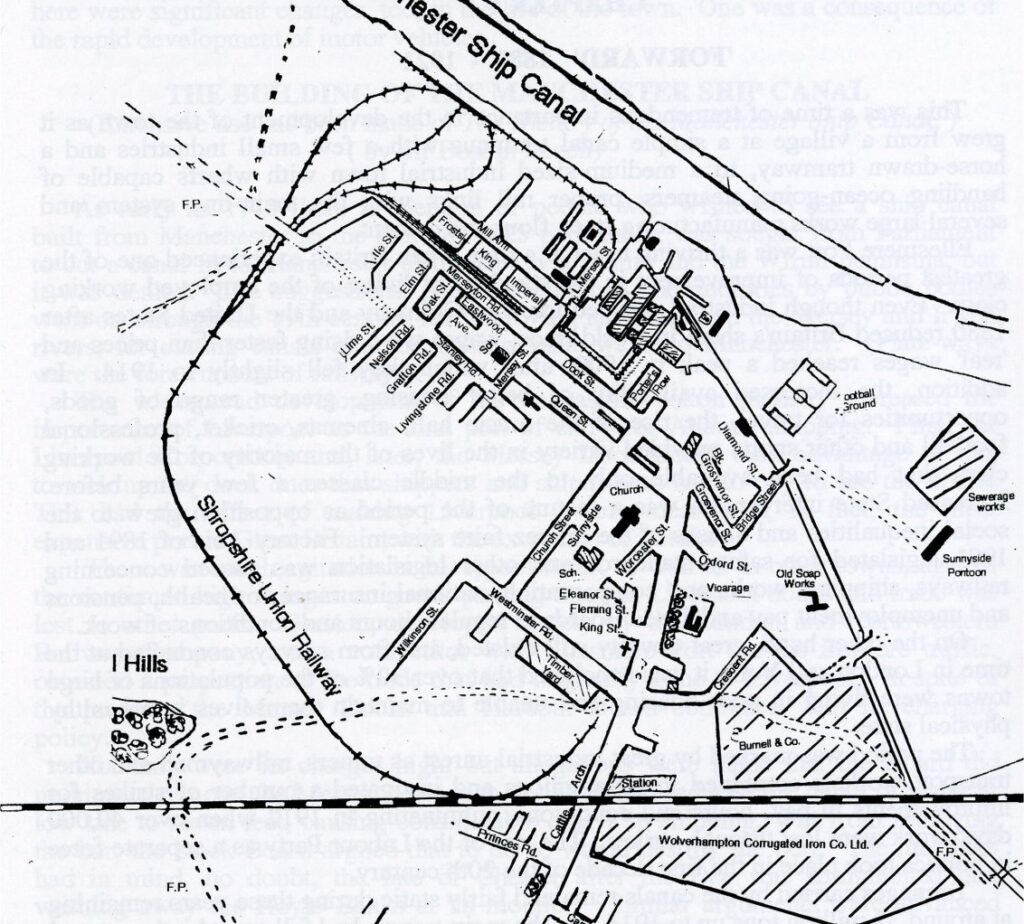

Joseph Powell Mercer was born in Higher Bebington on 21 July 1889. As a young teenager, he joined the local New Ferry Bible Class, and regularly played for their football team, before moving up a level to turn out for Bebington Vics. Then, from there to a team in Bolton; returning back home again to play two seasons in a soldier’s side based at Chester Castle; followed by a short, uneventful spell at Tranmere. His position was centre-forward, with an impressive scoring record. By this time in his late teens, he was also an apprentice bricklayer, while his football skills had come to the attention of the local Burnell’s Ironworks football team – Ellesmere Port F.C. – who were to turn him into a centre-half. Scouts soon became aware of his qualities and came calling, and on 14 December 1910, twenty-one year old Joe was snapped up by Nottingham Forest, then in the top flight, immediately making his debut for the reserves on 17 December. His friend and team mate in the Burnell’s side, Sam Chedgzoy, had signed for Everton just a few days earlier.

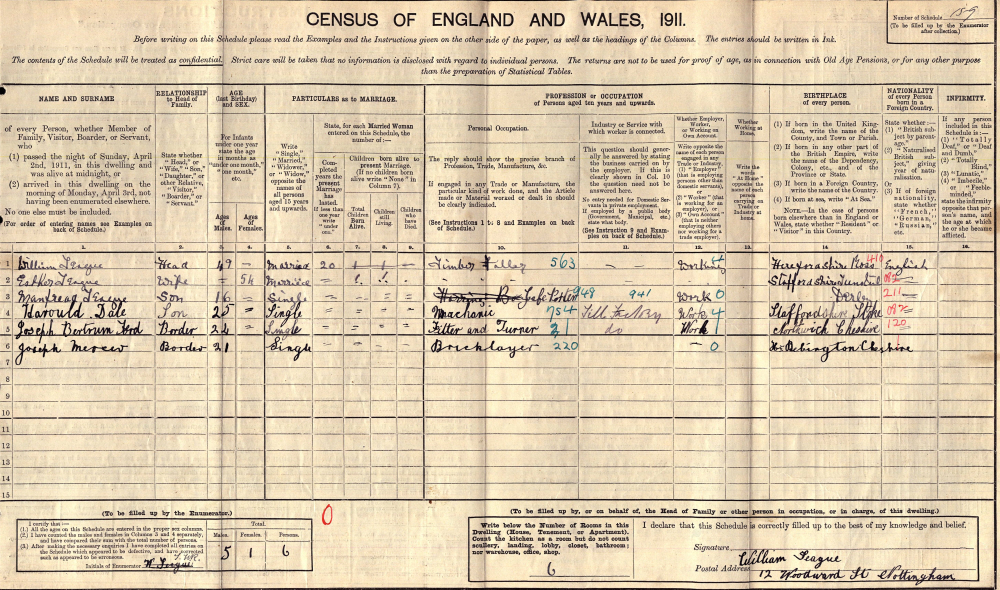

While in Nottingham he lived in digs, returning home during the summer break, where he carried on working in his ‘proper job’ on the local building sites. In June 1913, while back in the Port during the close season, he married Ethel Breeze in the local parish church of Christchurch. Joe still looked upon himself as a bricklayer, his true occupation – how times have changed for footballers; despite being in the first team in one of the most famous clubs, he still put down his occupation as bricklayer on the census form of 1911, and on his marriage certificate of 1913 – no mention of ‘footballer.’ He would go on to play a total of 158 regular first team games for Forest between 1910-1914, scoring six goals.

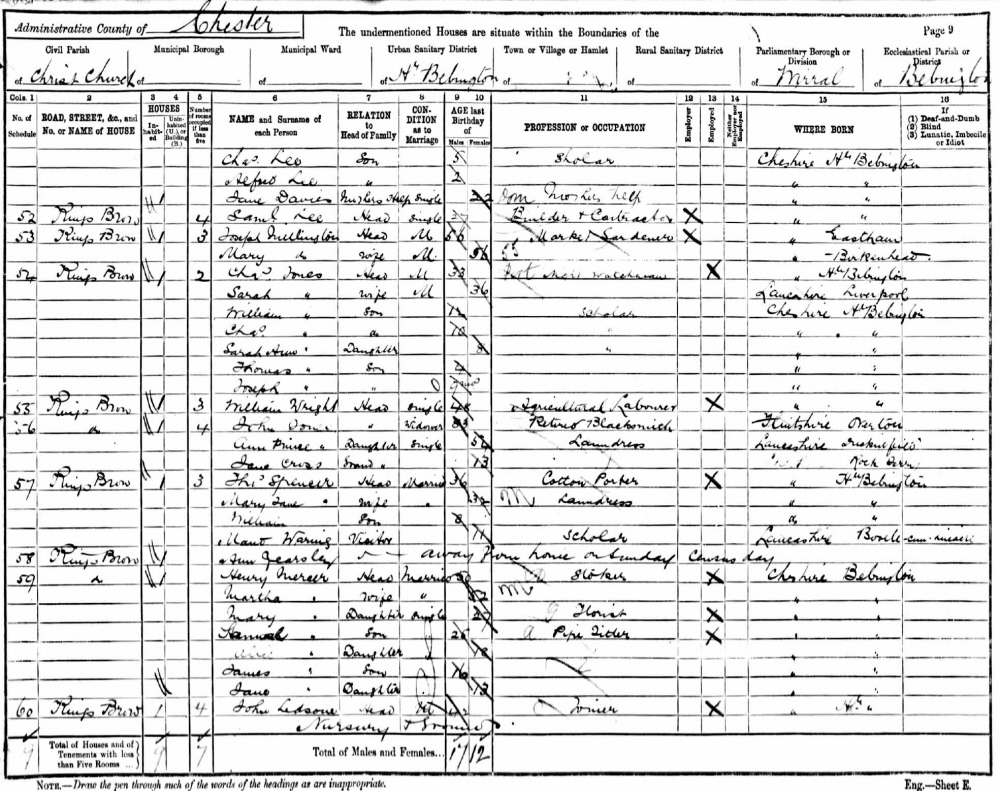

Joseph senior’s father Samuel and grandfather Henry (item 59)

Top entry under Samuel Mercer, Joe Mercer aged 11.

Joseph in his Nottingham lodgings while playing for Forest – still recorded as a ‘Bricklayer’

His footballing career did pay well however. The maximum wage was £4 per week, but even if he was earning less than this, he was still far better off than the skilled and semi-skilled who were averaging £97 and £63 per year respectively, and many of his contemporaries were unskilled labourers on much less than that.

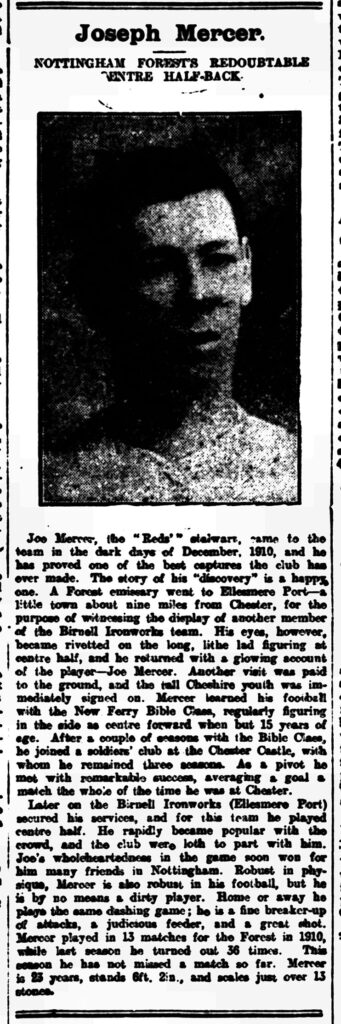

On 23 November 1912, Joe was featured in a player profile in the Nottingham Football News,

Joseph Mercer

Nottingham Forest’s redoubtable centre half-back

Joe Mercer, the ‘Reds’ stalwart, came to the team in the dark days of December 1910, and he has proved one of the best captures the club has ever made. The story of his ‘discovery’ is a happy one. A Forest emissary went to Ellesmere Port – a little town about 9 miles from Chester, for the purpose of witnessing the display of another member of the Burnell Ironworks team. His eyes, however, became riveted on the long lithe lad figuring at centre half, and he returned with a glowing account of the player – Joe Mercer.

Another visit was paid to the ground, and the tall Cheshire youth was immediately signed on. Mercer learned his football with the New Ferry Bible Class, regularly figuring in the side as centre forward when but 15 years of age. After a couple of seasons with the Bible Class, he joined a soldiers’ club at the Chester Castle, with whom he remained three seasons. As a pivot he met with remarkable success, averaging a goal a match the whole of the time he was at Chester.

Later on the Burnell Ironworks (Ellesmere Port) secured his services, and for this team he played centre half. He rapidly became popular with the crowd, and the club were loath to part with him. Joe’s wholeheartedness in the game soon won for him many friends in Nottingham. Robust in physique, Mercer is also robust in his football, but he is by no means a dirty player. Home or away, he plays the same dashing game; he is a fine breaker-up of attacks, a judicious feeder, and a great shot. Mercer played in 13 matches for the Forest in 1910, while last season he turned out 36 times. This season he has not missed a match so far. Mercer is 23 years, stands 6’2″, and scales just over 13 stones.

Nottingham Football News, 23 November 1912

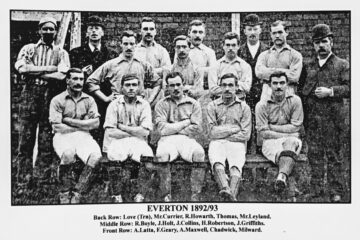

with the unmistakable figure of Joe Mercer in the centre of the back row

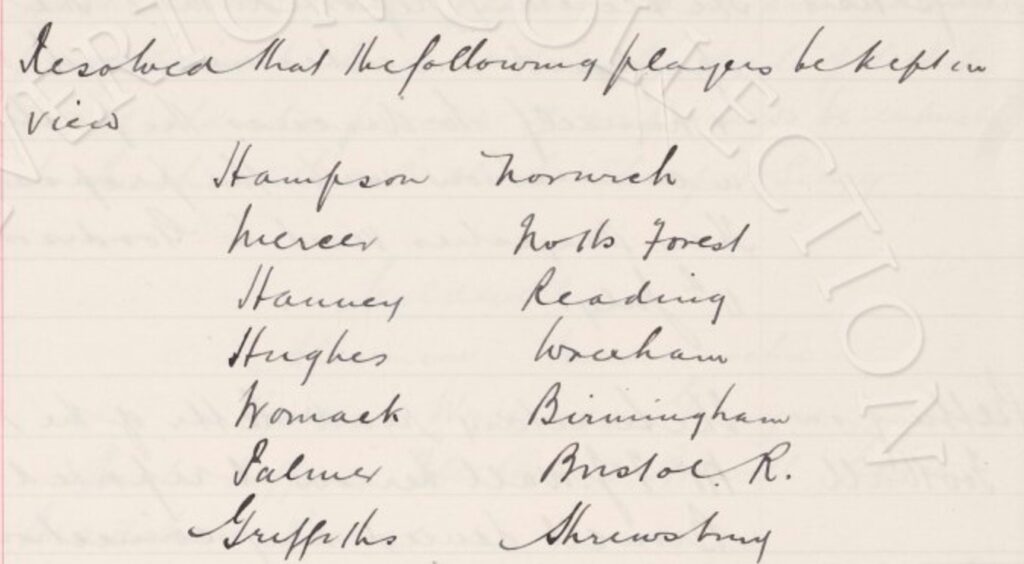

His reputation as a hard, tough-tackling centre-half began to grow, especially after a clash with former Everton star Harry Mountford, in a game against Burnley at Turf Moor in October 1911, which effectively curtailed the top flight career of the Claret’s forward. Everton were reported to have been interested in signing Joe, but Will Cuff thought him a little too rough around the edges for the Blues, commenting ‘He’ll get us thrown out of the league!’

During the 1913-14 season, Joe was regularly putting in impressive performances, and the local Nottingham journalist with the inspired pen-name of ‘Robin Hood,‘ stated in his weekly column,

Joe Mercer met with a painful injury to his face in heading the ball, but he stuck to his guns and played capital football. The big centre-half has touched great form in the last three matches, and if he studies his small faults, with age and physique in his favour, there is no reason why he should not one day be England’s pivot. I wish him luck. Nottingham Football News, 21 March 1914

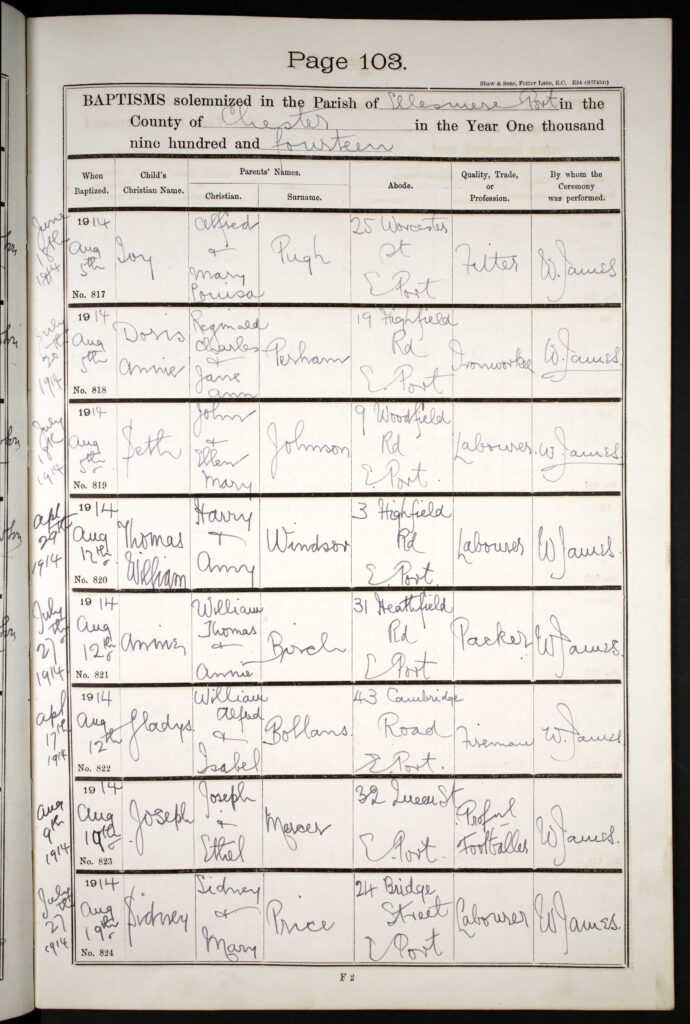

But at the peak of his playing career, the outbreak of hostilities put paid to any further aspirations on the footballing front. It must have been a week of tortured emotions for him, given that his young son, Joseph junior, the first of four children, was born just five days after war was declared on 9 August 1914, at their home in 32 Queen Street, Ellesmere Port (in those days there was a true close season, from the end of April until the beginning of September, and the Mercers had retained their family home). His infant son would also become a footballer, destined to one day manage the England football team.

Cheshire Observer, 11 July 1914

Of course, with the general misapprehension across the country that the war would be all over by Christmas, most footballers probably felt they should carry on playing, until the authorities – be it the F.A. or the government – told them otherwise. Inevitably, the focus of discussion on who ought to be serving soon turned to sportsmen. Pressure came, for example, from the author Arthur Conan Doyle, who appealed on 6 September 1914 for footballers to join the armed forces:

‘There was a time for all things in the world. There was a time for games, there was a time for business, and there was a time for domestic life. There was a time for everything, but there is only time for one thing now, and that thing is war. If the cricketer had a straight eye, let him look along the barrel of a rifle. If a footballer had strength of limb, let them serve and march in the field of battle.’

[On 28 October 1918 his son, Kingsley Doyle, died from pneumonia, which he contracted during his convalescence after being seriously wounded during the 1916 Battle of the Somme].

Others even verbally attacked the West Ham United players, calling them ‘effeminate’ and ‘cowardly’ for getting paid for playing football, while others were fighting on the Western Front. C.B.Fry, the well-known amateur footballer and cricketer, called for football to be abolished; all professional contracts be annulled; and furthermore, that no one below forty years of age be allowed to attend matches.

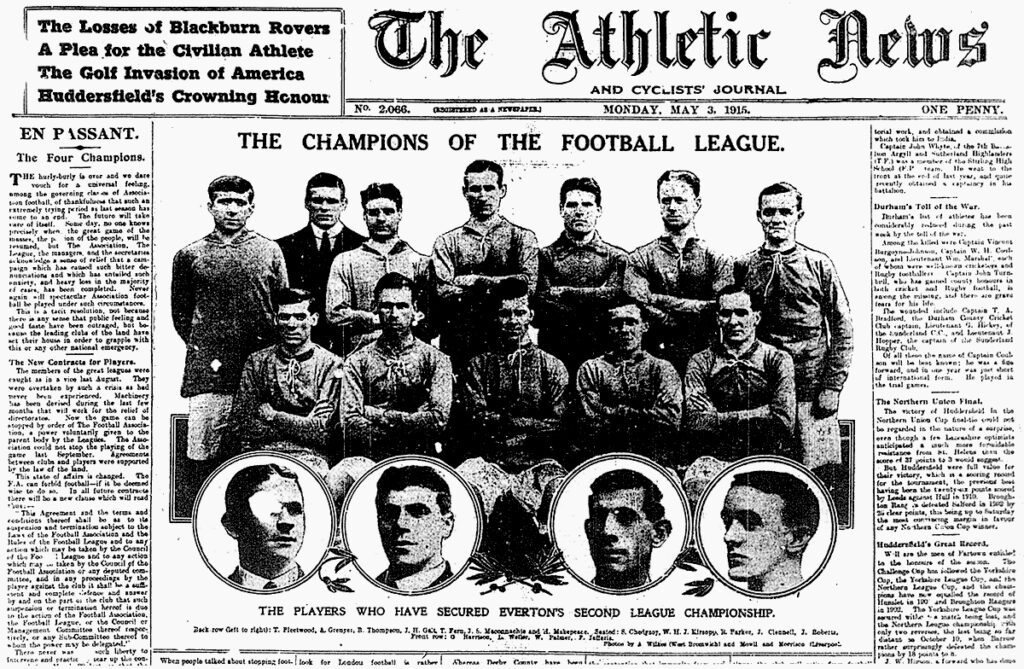

Eventually, the F.A. – after considerable pressure – called for clubs to release professional footballers who were not married, to allow them to join up, while the War Office worked with the F.A. to organise recruitment drives at games that were still being played. Sections of the press though saw this as an attempt by the ruling classes to stop the one single recreation enjoyed by the masses, on just one day in the week. The Athletic News angrily declared.

‘What do they care for the poor man’s sport? The poor are giving their lives for this country in thousands. In many cases they have nothing else… These should, according to a small clique of virulent snobs, be deprived of the one distraction that they have had for over thirty years.’

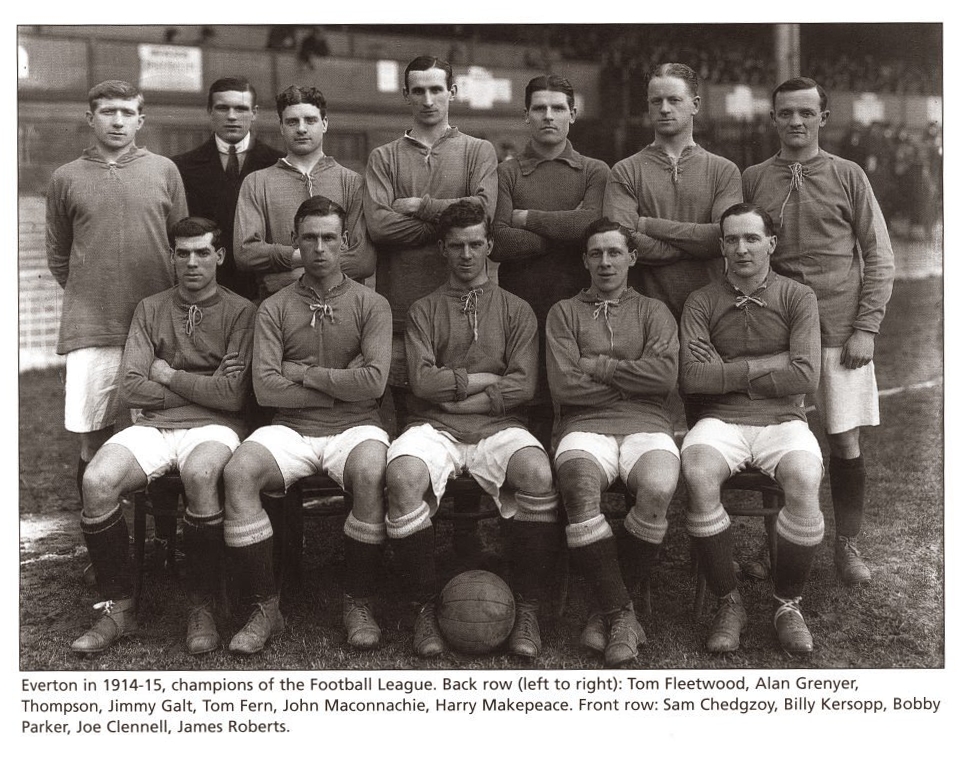

And so, the opinion of The Athletic uneasily prevailed, at least for now. League fixtures would continue until the end of the 1914/15 season, which saw Everton crowned champions, after which the competition was suspended until the end of the war. (Joe’s former team mate Sam Chedgzoy, was part of the championship winning side).

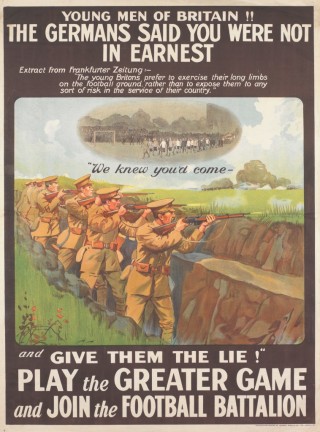

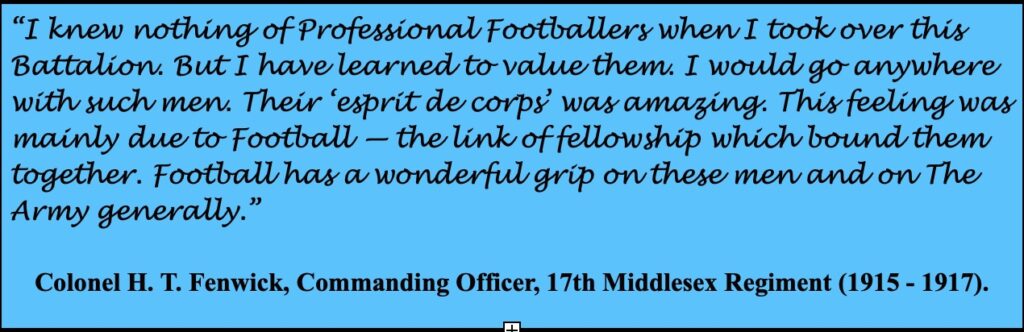

Many footballers did not wait for Christmas, and heeded the call by early December 1914, when the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment was established. Within a few weeks, the 17th Battalion had its full complement of 600 men. Not all were footballers however, as many recruits were local men who wanted to be in the same battalion as their football heroes. Nevertheless, by March 1915, it was reported that 122 professional footballers had joined the battalion. This was much lower than expected, and sportsmen, not just footballers, continued to come under pressure to enlist, not least for the example they would set to the masses – in the view of the recruiting organisers.

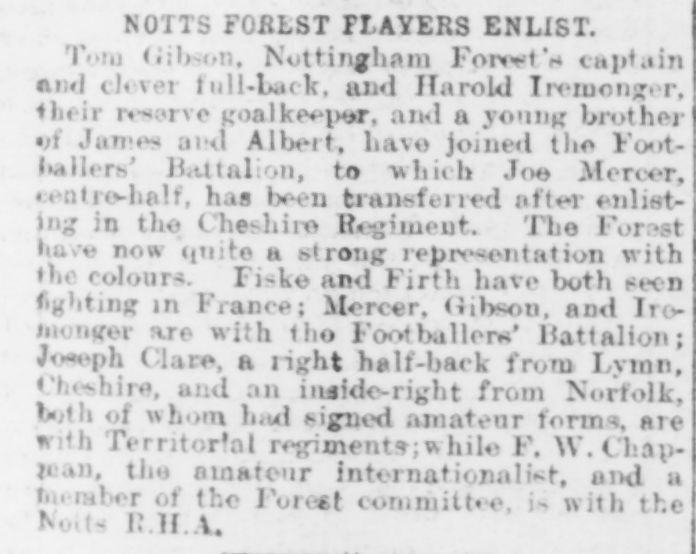

Joe Mercer presented himself at the Nottingham recruitment office on the morning of the 16 December 1914, and enlisted into the Cheshire Regiment. Most new recruits were posted to their local home regiment, or one with family links, especially if a relative had served in the Regulars or Territorials before the war. By December, many were were signing on for their local regimental ‘Pals’ battalions, a system of recruitment introduced to boost the numbers of volunteers who were encouraged to sign up with their friends or work colleagues. Faced with this option, Joe transferred to the Footballer’s Battalion the following day.

After months of training, Joe was posted to France, arriving on 17 November 1915, where the the battalion first experienced life in the trenches around Loos. Meanwhile, out of the front line, they played as much football as possible, including specially organised tournaments. Joe played in several games, home and abroad, including one representative match at Reading in front of a crowd of 3,000. While still at home during his basic training, Joe was also a guest player for the Liverpool Pals battalion;

During February 1915, there was a concerted drive on the Isle of Man to form a ‘Manx Pals’ battalion. It is quite possible that this match was arranged as part of that drive, and there was no better battalion to play against, and to publicise the cause, than the Liverpool Pals, the first such unit to be formed in the country. To line up against a star professional like Joe Mercer would certainly benefit the cause. There were new Manx recruits already based in Hoylake, soon to be joined by their new battalion, and it is likely that they supplied the team for this fixture. The following advert appeared the same day back home in the Manx press.

Within days, a thousand Manxmen had signed up.

The 1st Manx Service Company was formed just three weeks later on 1 March 1915. On 9 March, they sailed out of Douglas harbour to join the 16th Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment (Liverpool Pals), to begin basic training on Merseyside and North Wales, before being shipped out to Salonika in January 1916.

The 17th Service (Football) Battalion, Middlesex Regiment on the The Western Front

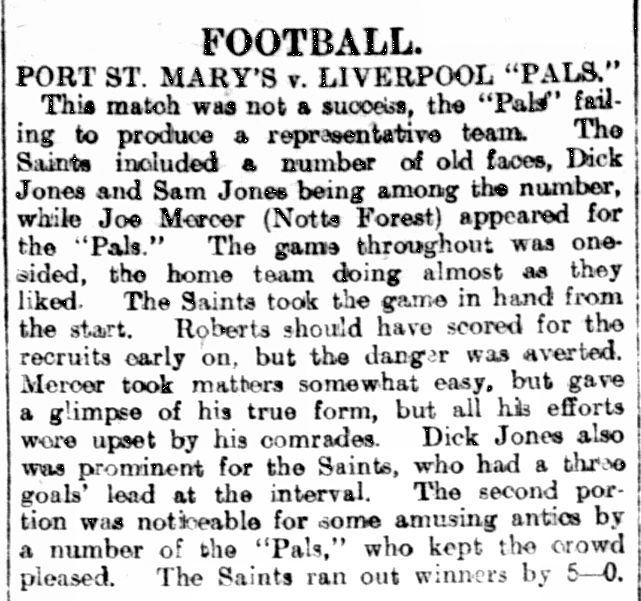

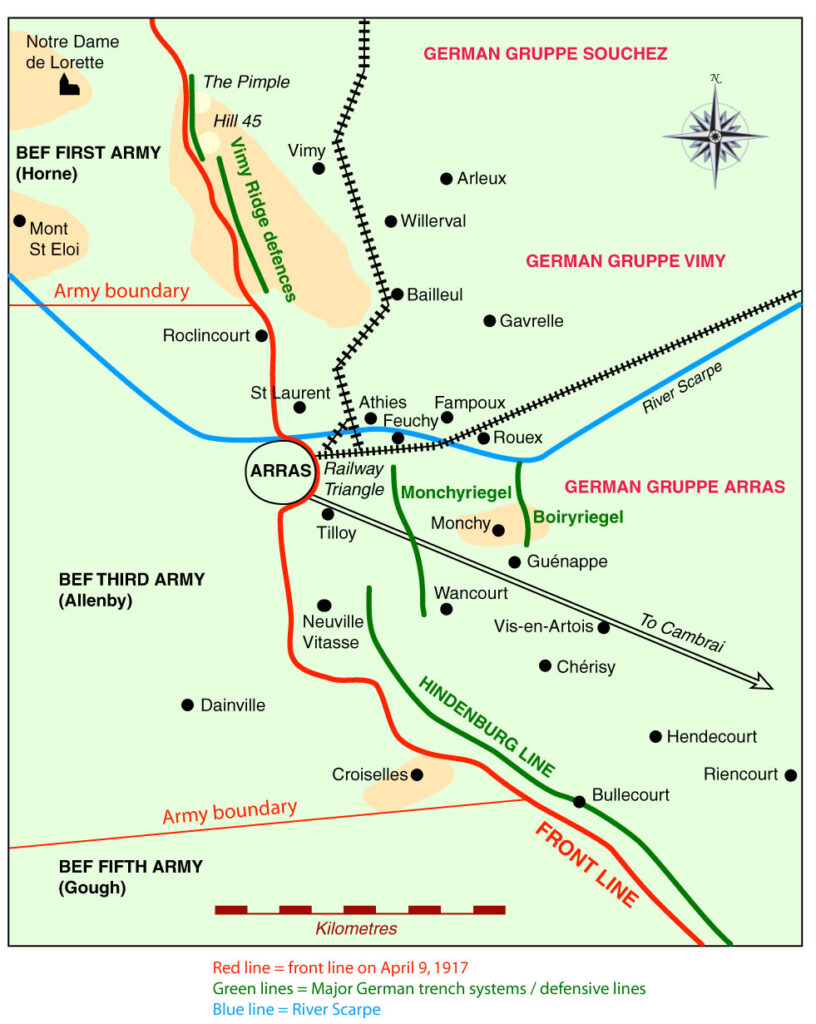

In late April/May of 1916, the Football Battalion moved south towards Vimy Ridge, where they took part in their first offensive action near Souchez. By July 1916, they had moved south again. The Battle of the Somme had commenced on 1 July, and the 17ths were moved to the British line east of Albert, where they were involved in heavy fighting at Delville Wood (27–29 July) and Guillemont (8 August). British casualties were very high across the front, and these actions devastated the 17th Middlesex to the extent that a draft of 716 men was needed to bring it back up to strength. At Delville Wood they lost 300 men in 1½ hours. Several footballers had been killed in action, while many others were among the wounded. Sergeant Mercer was wounded in the head by shrapnel in August 1916.

As the weather worsened and the Battle of the Somme was drawing to a close, the 17th Middlesex attacked the Redan Ridge on 13 November 1916, near Serre in the Battle of the Ancre. After weeks of heavy rain, some men sank up to their waists in the mud, and a heavy fog hung over the battlefield, limiting visibility to thirty yards.

Showing remarkable composure in the face of what was to come, two companies (B and D) of the 17th Middlesex went over the top playing mouth organs. According to the war diary containing the record of that day’s fighting, three officers were killed, two were wounded, with eight missing; fifteen other ranks were killed, plus 145 wounded and 133 missing.

Yet worse was to come. Moving to the north into the Arras sector once more, the 17ths were in the thick of the action in the Battle of Arras in April 1917. They fought through Oppy Wood on 28 April, into the small village of Oppy itself, only to find they were cut off and surrounded. The fight was desperate, and the battalion suffered its heaviest casualties in a single day, more than at any other stage in the war; eleven officers and 451 ranks were among the killed. They had lost over a thousand men overall in the Battle of Arras. Most of those who had survived, were either wounded or taken as prisoners of war. Lying in a shell hole for several hours during the barrage, and badly wounded in several places, Sergeant Mercer was captured by the enemy while attempting to return to the British lines.

Prisoner of War

If there was ever an inappropriate time to bring up a reference to an old score, this was surely it.

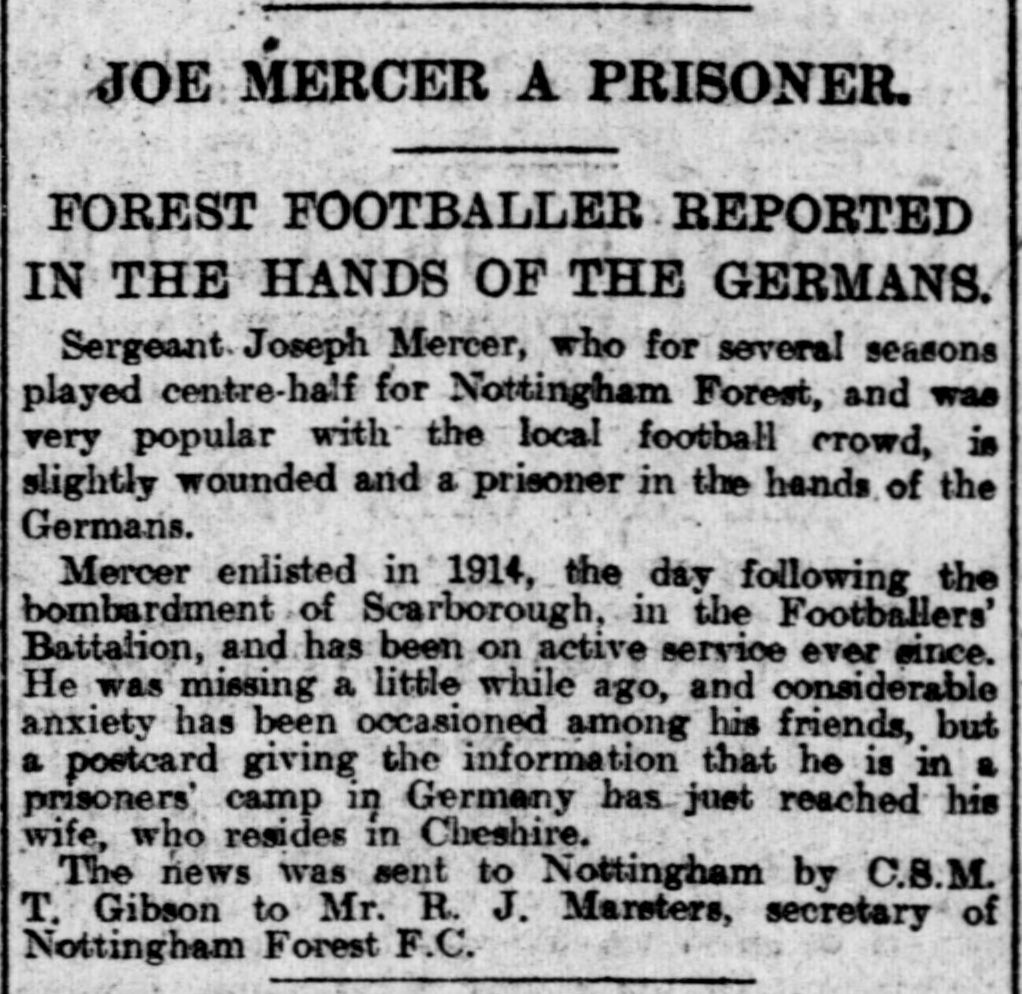

Meanwhile, behind the lines, following the annihilation of the Footballer’s Battalion at Oppy, Sergeant Mercer was posted as ‘missing’ – but of course, so were the majority of those lying dead on the battlefield, until they could be recovered and positively identified. It would be several weeks before anything was heard of his whereabouts – if he had survived at all.

To the relief of his family and friends, Ethel received a postcard with the briefest of messages, informing her that Joe was now a German prisoner of war.

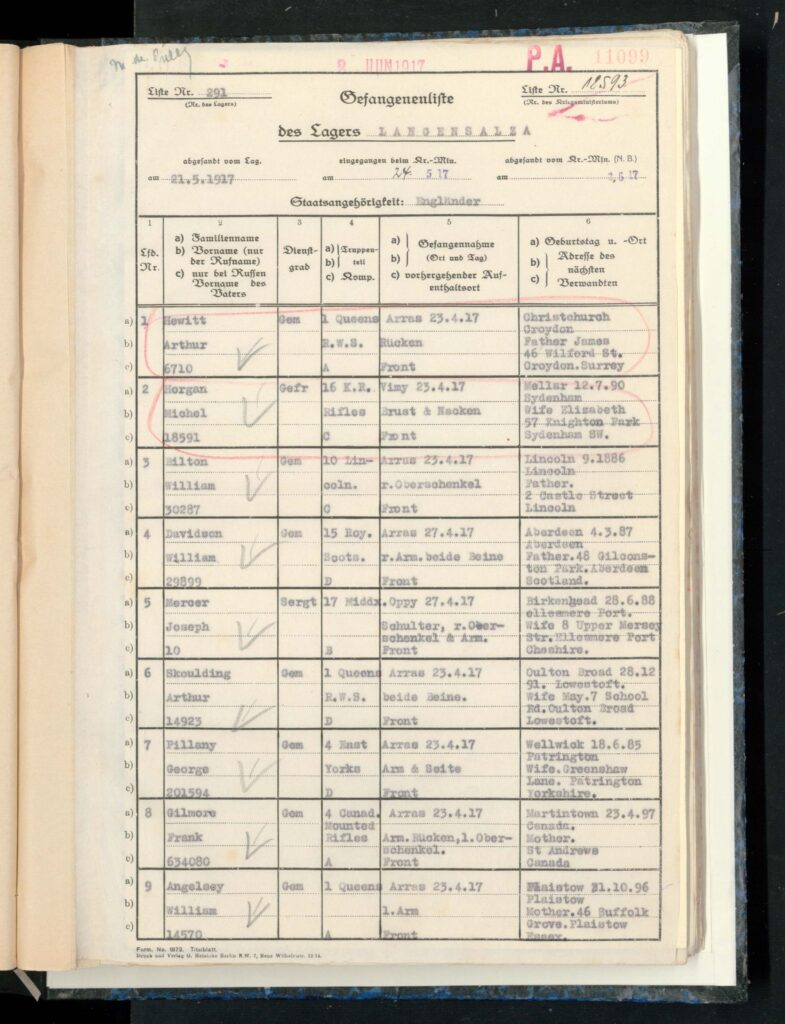

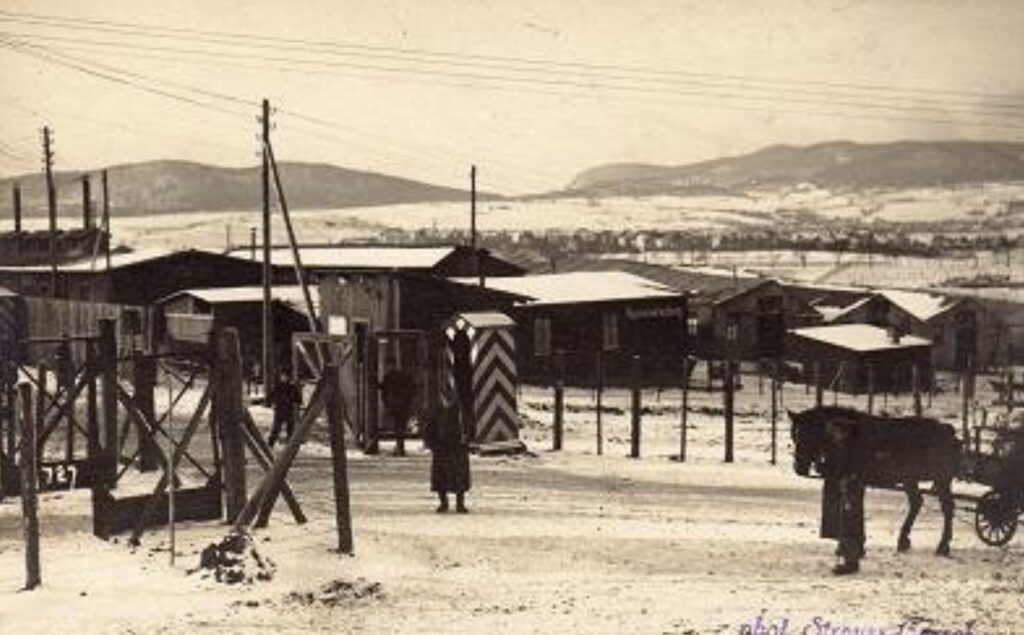

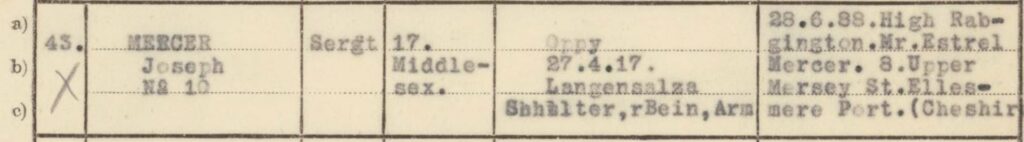

His first experience as a PoW, was to be taken by ambulance behind the lines to Douai to have his wounds treated, following which, he travelled for three days by train to reach Langensalza prison camp in Thuringia, where he spent more time recovering in the camp hospital. Once discharged, he was on the move again, this time to Giessen, where he stayed until 17 March 1918. From there he was transferred to Meschede in North Rhine-Westphalia, regarded by those who had experienced it, as one of harshest of the German camps. Meschede had a notorious reputation due to guards coming from the bottom echelons of the German Army, and their brutal treatment and exploitation of the Allied PoWs. It was here that Sergeant Mercer saw out the war. Once Armistice was declared, it would still be several weeks before he was discharged and despatched for home.

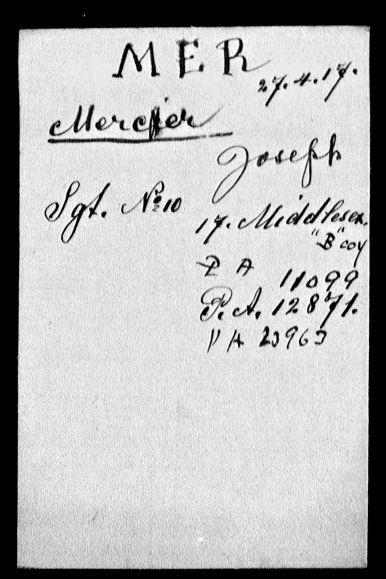

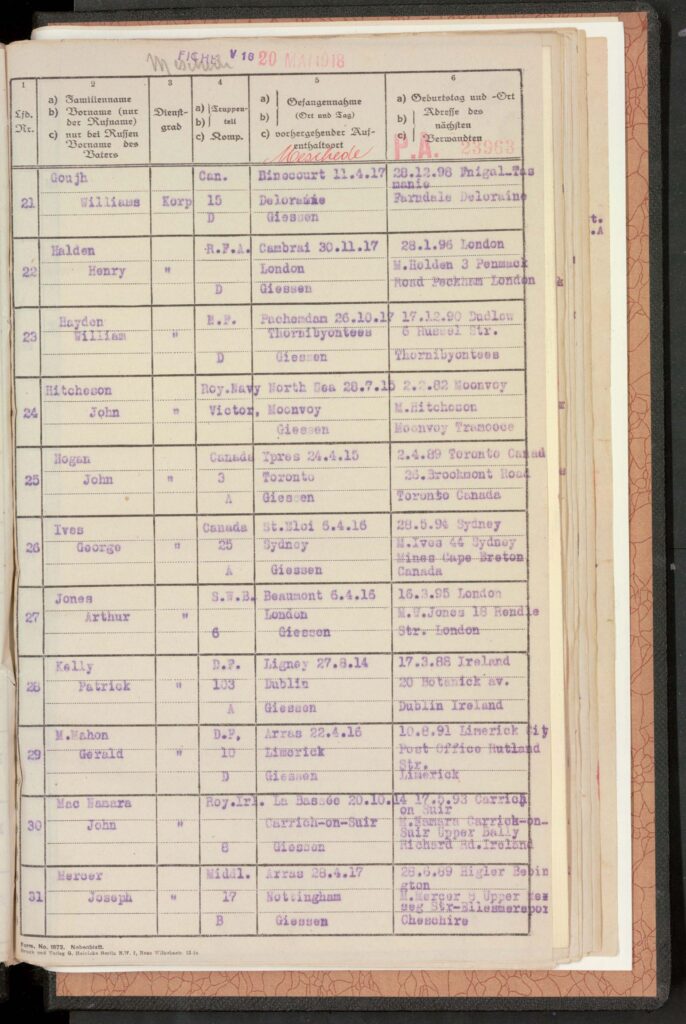

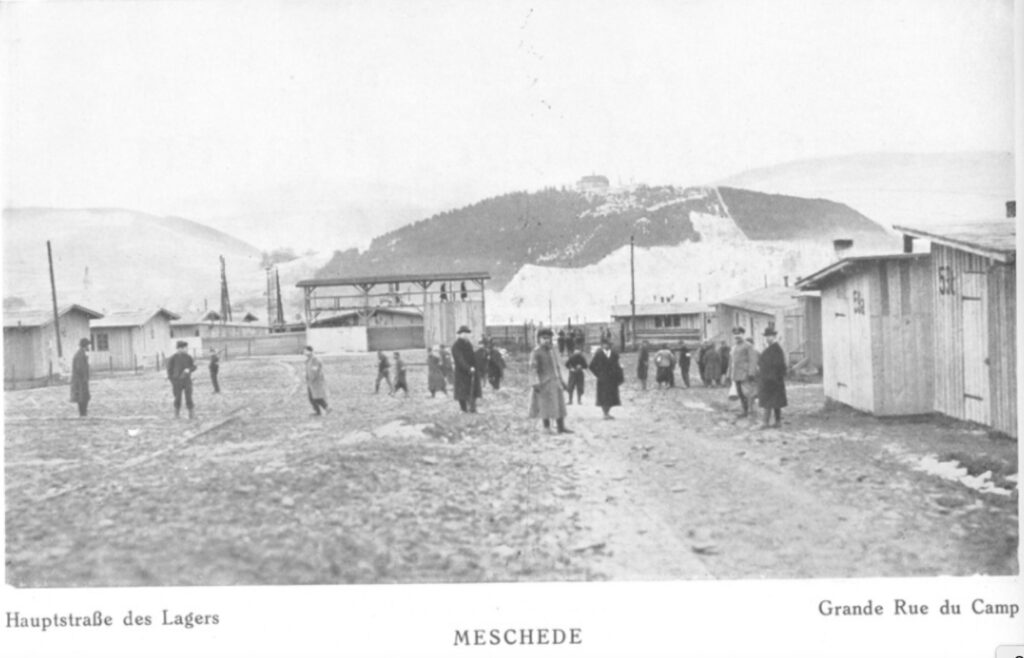

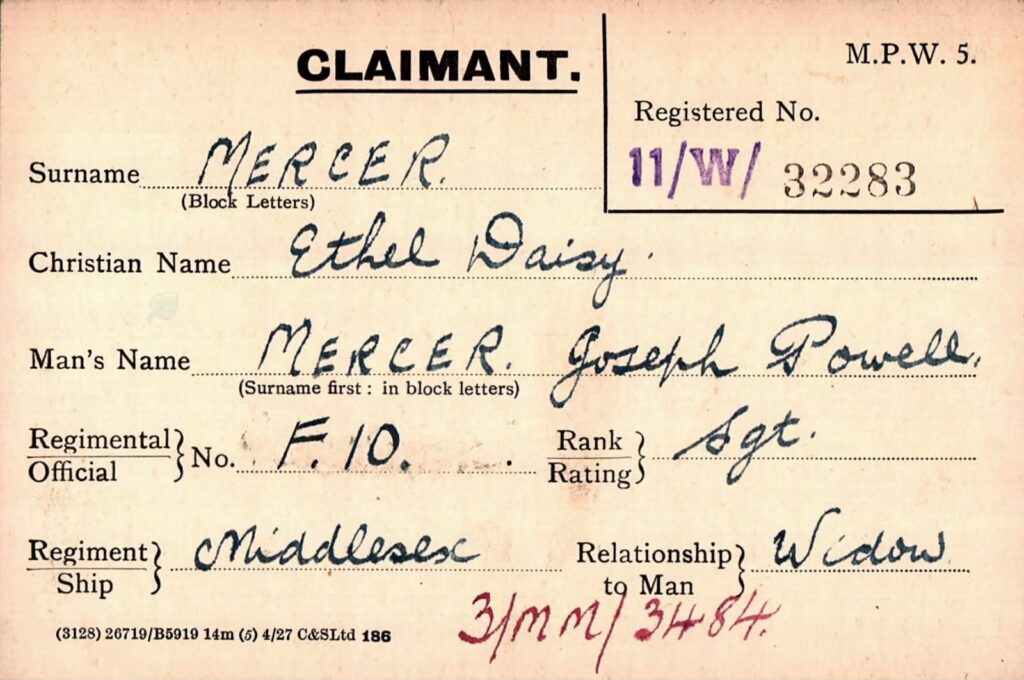

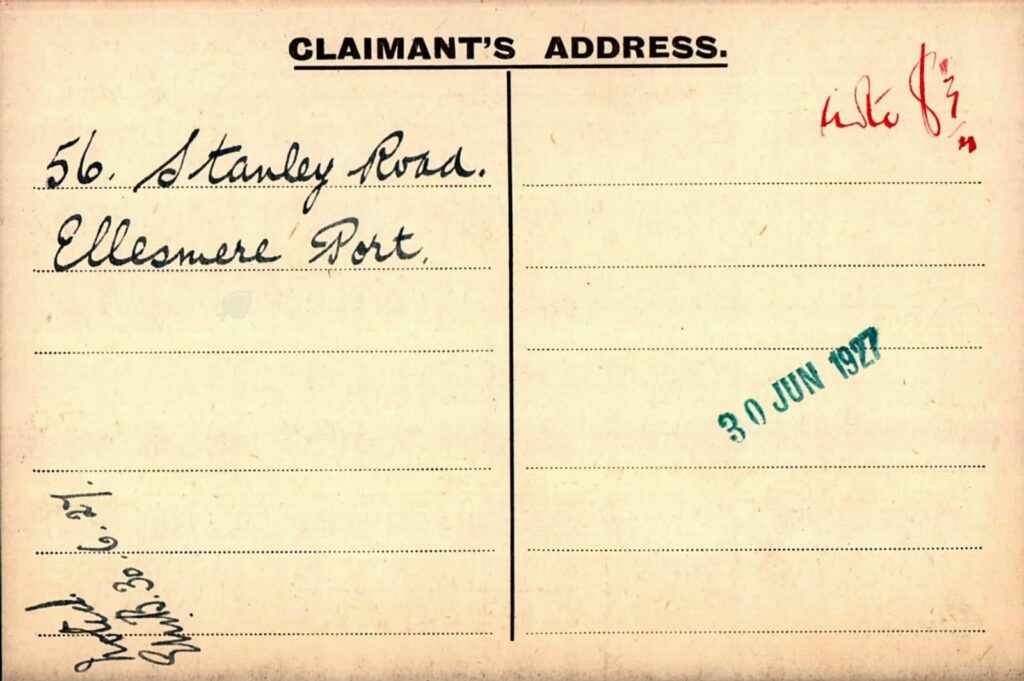

The discovery of Sergeant Joseph Mercer’s PoW index card in the above archive listing the key reference numbers, led to the retrieval of his PoW records shown below.

Joe Mercer recorded at Langensalza PoW camp on arrival 24 May 1917.

His date of capture and injuries – shoulder, thigh and arm – were also recorded

Joe Mercer recorded on arrival at Giessen PoW Camp 21 July 1917

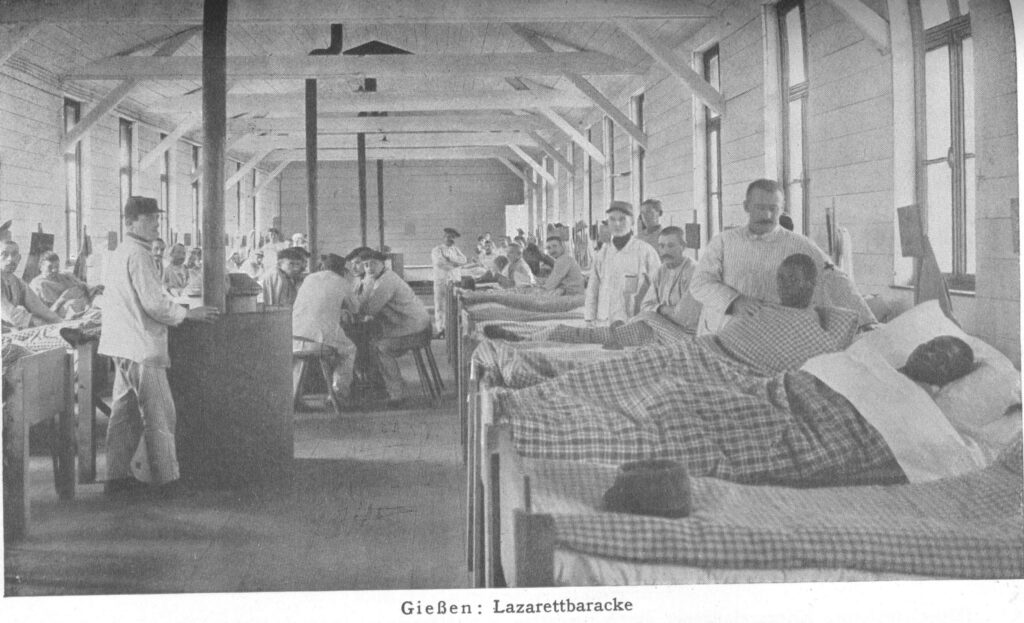

French orderlies provide care for the sick and wounded Allied prisoners in a hospital ward at Giessen. The beds are full of recovering soldiers and the ward is well heated by the large stoves in the centre aisle of the building.

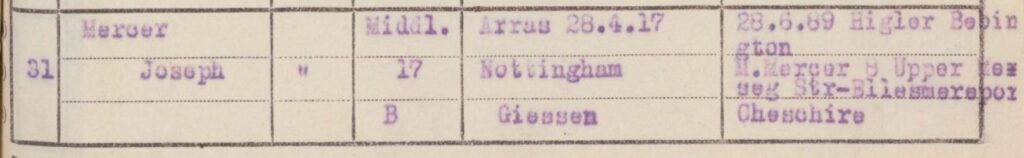

Joe Mercer recorded on arrival at Meschede PoW Camp, 20 March 1918

Probably taken in the Winter of 1914-1915. It provides a good view of the barracks lining the square and the hills surrounding the camp. German guards observe the activities from a bridge over a gate.

There are German officers and a number of civilians, who may be Red Cross or neutral embassy inspectors.

moved the short distance to 8 Upper Mersey Street.

Liverpool Echo, 19 March 1918

John ‘Tim’ Coleman MM (1881-1940) was an England international who made 71 appearances for Everton between 1908 and 1910, scoring 30 goals. He later became a team mate of Joe Mercer at Nottingham Forest, and also signed up in the Footballer’s Battalion. He was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in October 1918. He continued to correspond with ‘Bee’, (journalist of the Liverpool Echo football pages), throughout the war. By the time his letter appeared in the Echo, Mercer was already on his way to Meschede.

Coleman’s reference to the battalion break-up, was in regard to the 1st Football Battalion, 17th Middlesex, being disbanded in February 1918 due to manpower shortages in the British army. The remaining officers and men were transferred to other units.

[An excellent account of the life of Tim Colman by Rob Sawyer, entitled ‘Tim Coleman: A Rebel, a Soldier and an Entertainer,’ can found on ToffeeWeb.]

Any hopes that the majority of Ellesmere Port soldiers held in captivity would be home by Christmas were soon dashed, and the planned civic reception was put back to 22 January 1919, in the hope that all would have arrived by then.

In fact, such was the operation to get all the PoW’s home so huge, that a great many prisoners from all nations spent another Christmas in the camps. Some of their guards had upped and left as soon as the armistice was declared, while in other camps German officials tried to use the prisoners as bargaining chips for their own safe passage. By the end of November, only around ten per cent of British men had made it home, while only half had made it to allied lines by the end of the year.

Nevertheless, Joe had survived his injuries, and although he was not officially discharged until 14 April 1919, he was home (either permanently or on leave) by early January. He also took the opportunity to speak in more detail about his experiences to the Ellesmere Port local press on 4 January 1919,

Prominent Footballer’s Experiences

Ellesmere Port people are always interested in the career of Sergeant Joseph Mercer, the Nottingham Forest half-back, who at one time played for Burnell’s Ironworks. He is now one of Ellesmere Port’s repatriated prisoners of war, and thanks to his fine physique he has come through the ordeal well. He enlisted in the Footballer’s Battalion on 16 December 1914, and we may say at the outset, that he considers this battalion one of the finest for good comradeship that ever crossed to France.

He went over to France on 17 October 1915 [the medal card states it was 17 November] and after 20 months fighting in the line, was taken prisoner on 28 April 1917. The battalion was in some heavy fighting including Delville Wood, where they lost 300 men in 1½ hours. Sergeant Mercer was wounded in the head by shrapnel in August 1916. He was taken prisoner near Arras. His company went right through a village, but the right and left were held up and he heard afterwards that only two of the company got back. He was hit in the leg, and shot in the shoulder by a bullet. He lay in a shell hole for several hours and was under a British barrage for two hours being very thankful when it finished. Sergeant Mercer tried to get back to British lines, but ran into a German machine gun party, which settled matters.

He was taken to Douai in a motor ambulance, and then to Langensalza, a three days’ journey by train. The food was such that no wounded man could tackle it at all. He was pleased to see Britishers helping in the hospital and later got in touch with Jim McCormick, Plymouth Argyle’s right half-back who was a great help. The food at Langensalza was terrible, and often included raw fish and black bread and coffee twice a day. Only the Russians could eat it, and they were from behind the line, almost at starvation point. Sergeant Mercer states it reminded him more than anything of Woodward’s sea lions.

He afterwards was sent to Giessen, and here the other prisoners shared their parcels until those for the newcomers arrived from home. At this camp five-a-side football contests were arranged. The prisoners subscribed half a mark each towards the prizes, and the sides were picked in fives as the names came out of a bag. They had to buy wood from the Germans to make goalposts, and nets were made from string taken from parcels received from England. An amusing feature of the contests was that the Germans would not allow the referee to use his whistle because it excited the guard. He had to use a little bell and even at times a mouth organ. To enable the British to have their usual ‘flutter’, a book was made on the matches. The prizes for the contests were all given in cash.

The commandant at Giessen was usually very fair and held the British up as a pattern to other nationalities in the camp for their cleanliness, not that he loved the British any more for it. The commandant at Meschede once met a prisoner coming from the stores carrying two tins of food. The man was too loaded to salute – the commandant led him to a drain and made him pour the contents of the tins down the drain. Later, he had to do fourteen days ‘strafe’.

Sergeant Mercer left Giessen for Meschede on 17 March 1918, and his new camp was known to be one of the worst in Germany. The prisoners were non-commissioned officers, men who were no good to the Germans for work, which meant a great deal. The distributions methods were such that they stood very little chance of getting their parcels. One portion of the camp was set aside to receive men of all nationalities who had been working behind the lines. Those who lived through this ordeal were in a terrible state, but quite 25 per cent died, and as many as five Britishers were carried from the train dead on arrival at the camp. No one had been allowed to take them any food, the prevention of disease being the excuse made by the Germans, and special guards were provided carrying switches of barbed wire with which they used to strike at any prisoners trying to take food over the fence. One day, one or two N.C.O.s were allowed in to take in the names of newly arrived prisoners. A man brought in a bath of so-called soup, and the starving prisoners absolutely mobbed him. There was such a rush that as soon as one man got a bowl full it was upset in the crush and all the soup was wasted.

Efforts were made to start a British Help Committee at this camp, and despite all German efforts to stop it, it was eventually carried through, mainly by the efforts of Petty Officer Brooks of the R.N.A.S., a neutral named Rogeburg of the North American Y.M.C.A., and Sergeant Mercer. It took about four months to get going, but was of great benefit afterwards, bulk supplies of parcels being obtained, which kept the men going until the parcels came from home. The camp accommodation was ten thousand and when the Armistice was signed this number had increased to 22,000 by men coming into the camp from working parties. Men were walking about all night and things were very bad.

The camp authorities asked the prisoners to appoint delegates to visit Army Headquarters, but the British refused to do this, saying it was against their discipline. The German idea was to get the Armistice terms moderated. En route to the frontier, it was pitiful to see the German women and children without food and the prisoners gave a good deal away, even of the little they had. While at Meschede, the Germans pillaged the prisoners’ supply of medicine, in fact, the Help Committee wrote home to ask the Depot at Hove not to send further supplies. A tunnel was made at Meschede with a view to escape, but it was discovered by the Germans, and the prisoners from the whole barrack, about 250, had to do 21 days “dark cells” in batches of thirty.

Sergeant Mercer was not ill-treated himself, and says that the Germans never tackled anyone strong – it was always the poor chaps from behind the lines who had no strength. He adds that it was fine the way the Britishers stuck together under all circumstances, and if a man is a prisoner of war it soon brings out the bad or good in him.

Except for the stiffness in his arm, Sergeant Mercer is sound in wind and limb, and soon hopes to be able to take up football in real earnest’.

Chester Observer, 4 January 1919

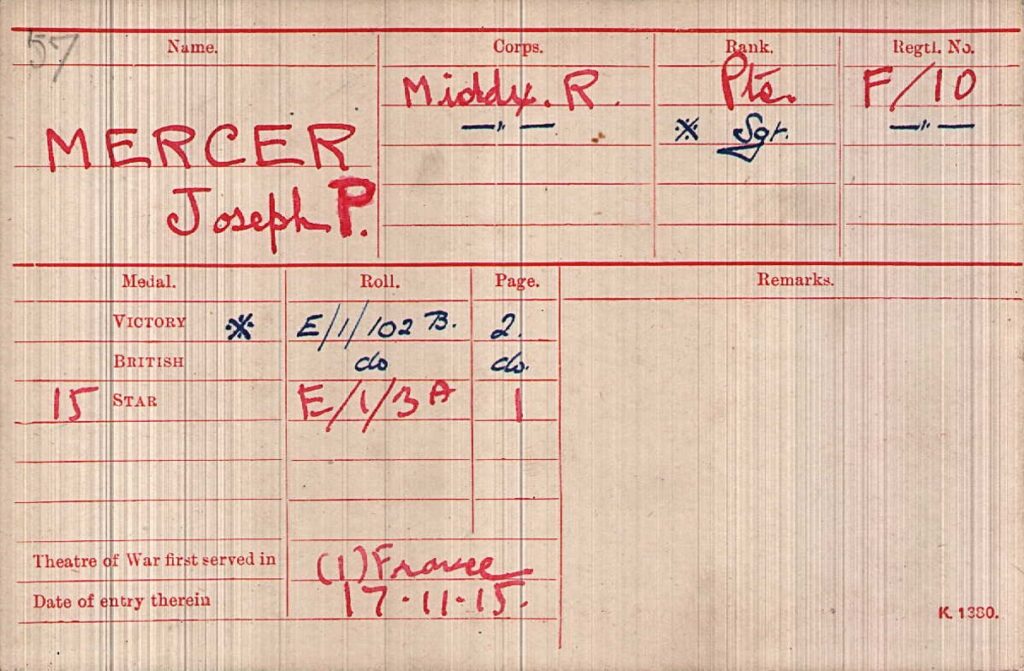

Confirmation that he was to be issued with the service medals pictured below.

According to the Medal Card for Sergeant J.P. Mercer, he was awarded (left to right) the 1915 Star, the British Medal and the Victory Medal

Unveiled in Longueval, France on 21 October 2010. The memorial honours the soldiers who fought in the 17th and 23rd (Service) Battalions of the Middlesex Regiment during World War I.

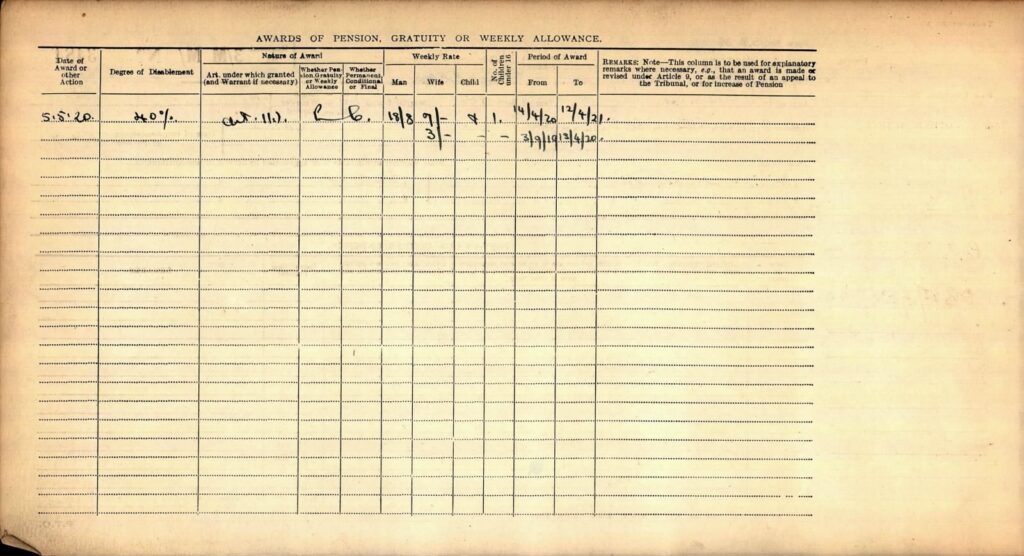

From the day Sergeant Mercer was officially discharged, he was awarded a disability war pension due to the injuries he had suffered, but in particular, the bullet wound to his shoulder, which continued to give him problems for the rest of his life.

Joe Mercer and family are recorded living in 1 Flatt Lane in Ellesmere Port. Joe has returned to his pre-war occupation as a bricklayer, working for local builder E.J. Gould, while playing football for Tranmere Rovers

After the war, Mercer attempted to resume his career with Nottingham Forest, but after five years away he knew he would have to drop to a lower league, and he returned to his Wirral home to sign for Tranmere Rovers in 1920, in time for the start of the 1920/21 season. During that period, the Tranmere first team were playing in the Central League, and Joe was appointed club captain. However, his injury wracked body was to suffer yet again, when in the first Central League game of the season against Aston Villa, he had to be taken from the pitch to hospital by ambulance after fracturing his jaw.

Joseph Mercer is fifth from the right, back row

The next season – 1921/22 – was the first season of league football played by Tranmere Rovers. They now competed in the newly instituted Football League Division North (known as the Third Division (North)), winning their first fixture against Crewe Alexandra 4-1 at Prenton Park on 27 August 1921. Joe made 18 appearances in total, scoring once in a 4-0 defeat of Lincoln on 25 February 1922.

(Tranmere Rovers 1921-22 season)

Sadly, the injuries to his body were taking their toll, and prevented him continuing further, and he was forced to retire from the game. By 1927, he was hospitalised and in decline. By April, he was in a sanatorium and given just weeks to live.

Considering he had taken a bullet to the shoulder, shrapnel in the head, wounds to the leg, then resumed a physically demanding career, it is a shock to find that his premature death aged just 37 in May 1927 was caused by the long-term effects from a gas attack in the trenches ten years earlier. To have coped with such handicaps in his post-war career is remarkable. Something to consider next time the latest overpaid prima donna dives like a swan and rolls over half a dozen times, after a passing defender just happened to cause a heavy draft of air turbulence. When Mercer went down, he really had been shot.

He was far from forgotten on Merseyside, and news of his passing was featured on the front page of several newspapers, including the Liverpool Evening News on 23 May 1927 (left). Joe was interred in the Ellesmere Port Overpool Cemetery, while his wife Ethel and four young children mourned his passing.

…………………………………………………………………

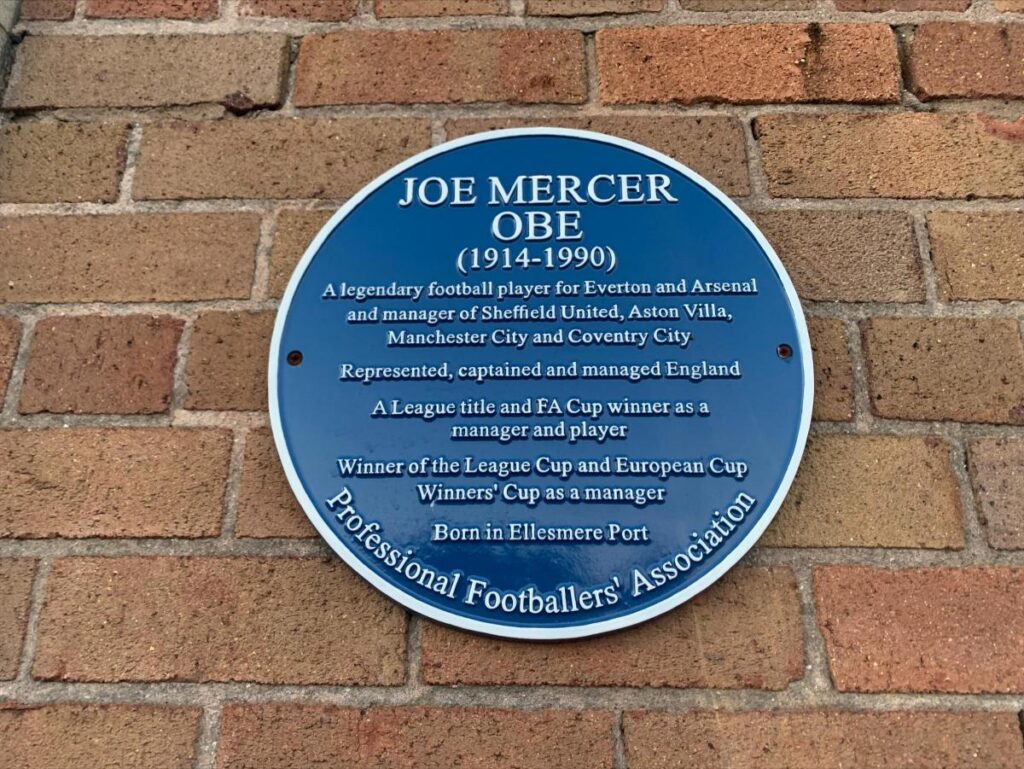

Joseph Mercer OBE (9 August 1914 – 9 August 1990)

Joseph Mercer junior was only twelve when his father died. He regularly watched his father play for Tranmere, although by then he was well past his best. By thirteen, young Joe had already started to shine, originally playing as a striker like his father.

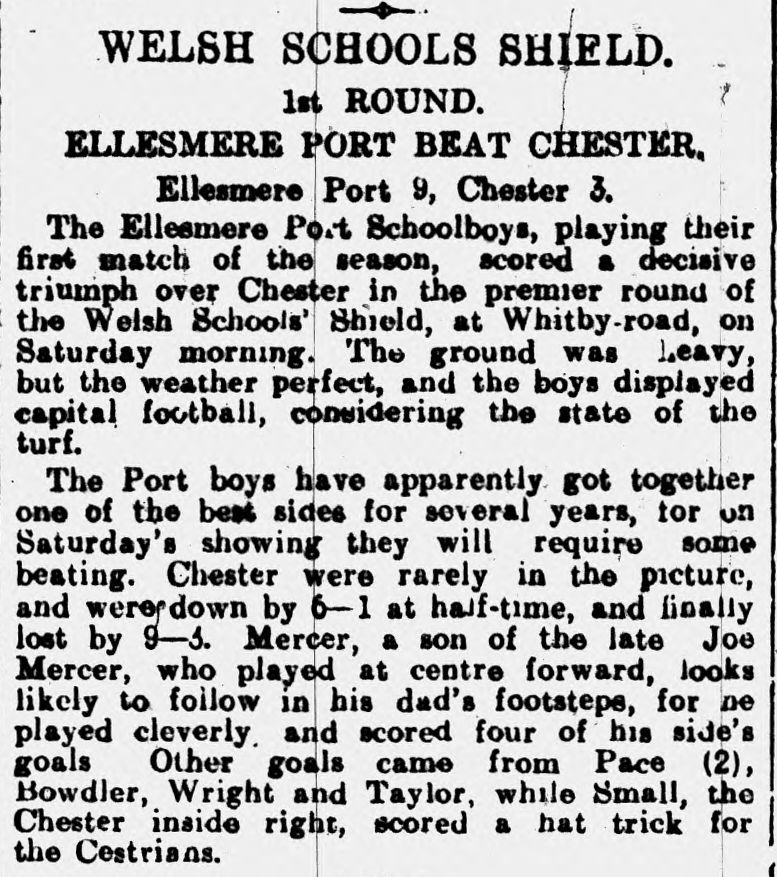

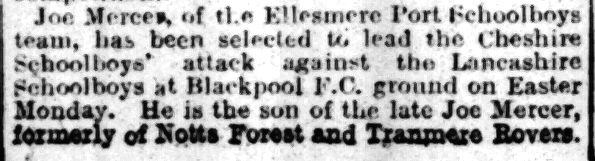

Chester Chronicle, 3 December 1927

Staffordshire Sentinel, 7 April 1928

It wasn’t long before Burnell’s (Ellesmere Port Town) came knocking once more on the door of the Mercer household, and, following in his father’s footsteps, Joe signed up.

Word soon reached the scouts at Everton, and in 1932, at the age of eighteen, he signed for the Blues, where he spent fifteen years, winning a championship medal and captained the side, before having his own career interrupted by war like his father.

After serving in the war as a PT instructor at Aldershot, Joe moved to Arsenal where he spent nine years captaining them to two FA Cup finals, and two league championships. He played twenty-seven times for England, and also captained his country. After a serious leg injury finished his playing days, he had a successful career in management, culminating in a caretaker manager role of England in the 1970s. After suffering from Alzheimer’s in his latter years, Joe passed away peacefully at home on his seventy-sixth birthday in 1990.

On 18 November 2021, a civic tribute took place in Ellesmere Port, when Joe Mercer junior was remembered by his home town with a reception and the unveiling of a blue plaque. Family members, plus former players from the clubs he was associated with were also present, including Mike Summerbee, Peter Reid, Graeme Sharp, and Graham Taylor of the PFA.

Supporters from across the football spectrum, including members of Everton FC Heritage Society, came together in Ellesmere Port last Thursday, 18 November, to celebrate the life of Joe Mercer — one of the town’s greatest sons. A plaque commissioned by football historian Mark Metcalf, with the support of the PFA, was unveiled at the Civic Hall.

by Rob Sawyer – see ToffeeWeb article here

**************************************************************************

Bibliography

Riddoch, Andrew; Kemp, David (2010). When the Whistle Blows: The Story of the Footballers’ Battalion in the Great War. Sparkford, Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Publishing. p. 264.

Riddoch, Andrew, The Football Battalions, Football and the First World War (online)

Royden, Mike, Ellesmere Port War Memorial Project website www.eportwarmemorial.org.uk

Royden, Mike, Canal Port at War; the Story of Ellesmere Port During the First World War (2014) (Unpublished, but extracts can be accessed on www.eportwarmemorial.org.uk and a large part covering the home front was adapted in Royden, Mike, Village at War – the Cheshire Village of Farndon During the First World War (published 2016).

James, Gary, Football with a Smile: The Authorised Biography of Joe Mercer, OBE. (1993) ACL & Polar

Jackson, Alexander, The Greater Game: A History of Football in World War I, National Football Museum 2014).

International Committee of the Red Cross, Historical Archives 1914-1918: Prisoners of the First World War (Online) – https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/en

Everton FC Minutes of the Board of Directors, (The Everton Collection – Liverpool Record Office)

Newspapers;

Various newspapers, including;

Chester/Cheshire Observer

Chester Chronicle

Ellesmere Port Pioneer

Birkenhead News

Liverpool Echo

Athletic News

Nottingham Evening Post

…………………………………………………………………………………

| There is a PDF copy of this article available for download on Mike Royden’s History Pages Website. Please click image. |

…………………………………………………………………………………

Mike Royden, with former EFCHS member Peter Jones, has compiled the ‘Fallen of Everton Football Club‘ booklet, and has produced films on Remembrance at Everton FC. (Click image for more details and free PDF download of the booklet).

He is also working on a current project with Lewis Royden, Tony Wainwright and Peter Jones, to film short biographies of the Fallen of Everton FC. The first to be completed is about Private Don Sloan and can be found by clicking the link.

.

.……………………………………………………………………

A lovely response from The Forest Preservation Society @ForestPresSoc on Twitter.

Much appreciated!