Rob Sawyer

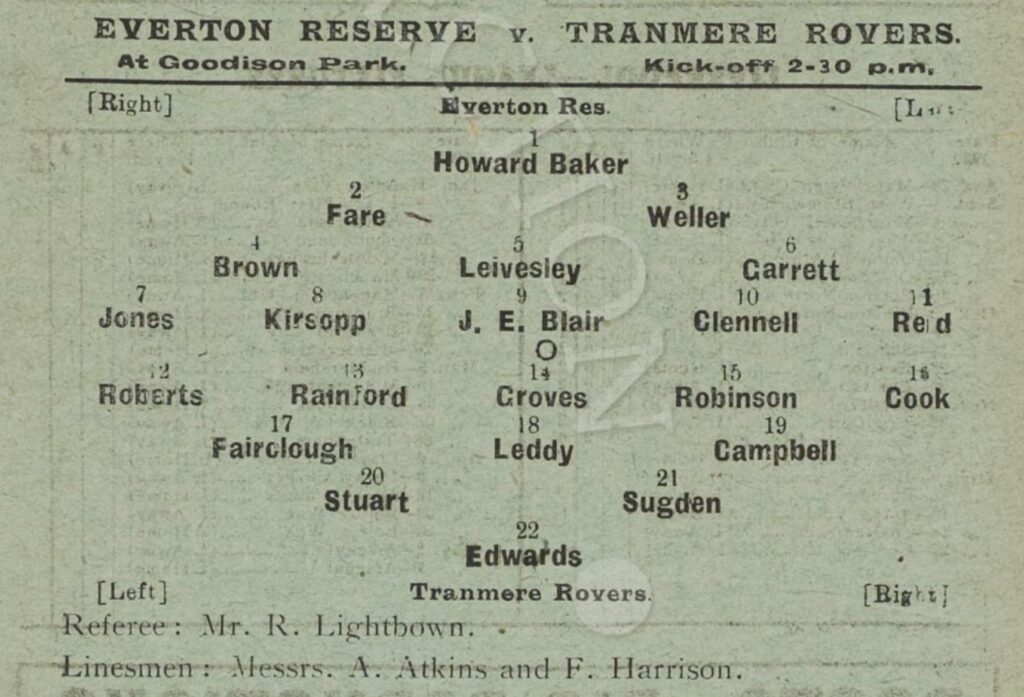

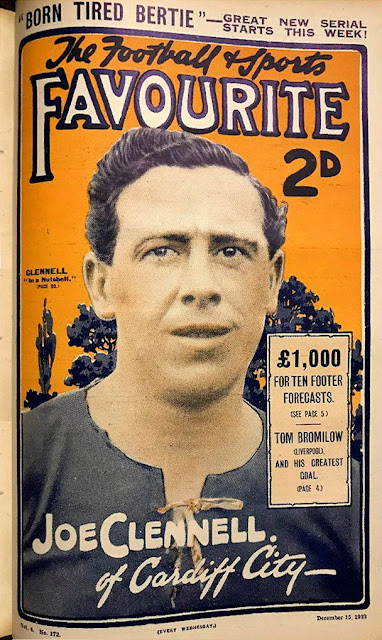

Although Bobby Parker’s goalscoring exploits may have grabbed the headlines as the Toffees advanced on the Football League title in 1915 – a triumph largely overshadowed by the spectre of the First World War – he was but one member of a strong royal blue attacking line. Sam Chedgzoy, on the right wing, was near the start of a long and illustrious career for Everton and England, which extended into the Dixie Dean era. Frank Jefferis, at inside-right, had garnered England honours having moved to Merseyside from Southampton. George Harrison was a great provider of assists from the left wing. While operating as the link man between Harrison and Parker was Joseph ‘Joe’ Clennell.

Joe was one of many players from Tyneside and Wearside, that famous cradle of football talent, to give excellent service to the Goodison Park club. Born on 18 February 1889 in New Silksworth, Joe was raised by parents Thomas (a coal miner) and Mary. When the 1891 census was taken, the infant Joe was living with his parents and two siblings at 21 Francis Street in Bishop Wearmouth, close to central Sunderland.

Sadly, there was bereavement in the Clennell household. Margaret died in 1894, aged two or three and Thomas Clennell died in 1895. Widowed Mary married again, this time to James Smith, a slater who had lost his wife. The blended household of the Clennells, plus James and his three children, lived at 77, Castlereagh Street, Village, Tunstall. Joe started his schooling, at the age of six, at New Silksworth Council School (formerly New Tunstall National School).

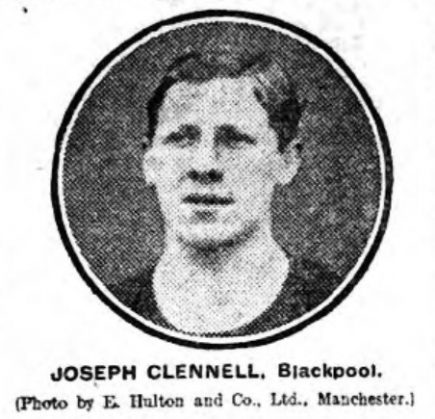

Initially an outside-left in schools football before finding his true calling by moving to inside-left in the forward line, Joe played for local side Silksworth United, members of the Sunderland and District League. He progressed to Seaham Harbour of the North Eastern League. Topping the scoring charts in each of his two seasons with the latter (scoring 33 in 1909/10), he became the subject of interest for Football League clubs, but for whatever reason, evaded the nets of Sunderland and Newcastle, instead, at 21, joining Blackpool FC on the Fylde coast. He lodged with three other footballers from the North East with a landlady on Reads Road.

In December 1910, Athletic News (Athletic News and Cyclists’ Journal, to give it its full title) carried a feature on the Blackpool team, and it was clear that the recent recruit was already making a name for himself and Bloomfield Road and beyond. Amid interest from several clubs, it was Blackburn Rovers who made the decisive move, bringing the forward across the county in April 1911, with him having made 33 appearances for the Tangerines, scoring an impressive 19 goals.

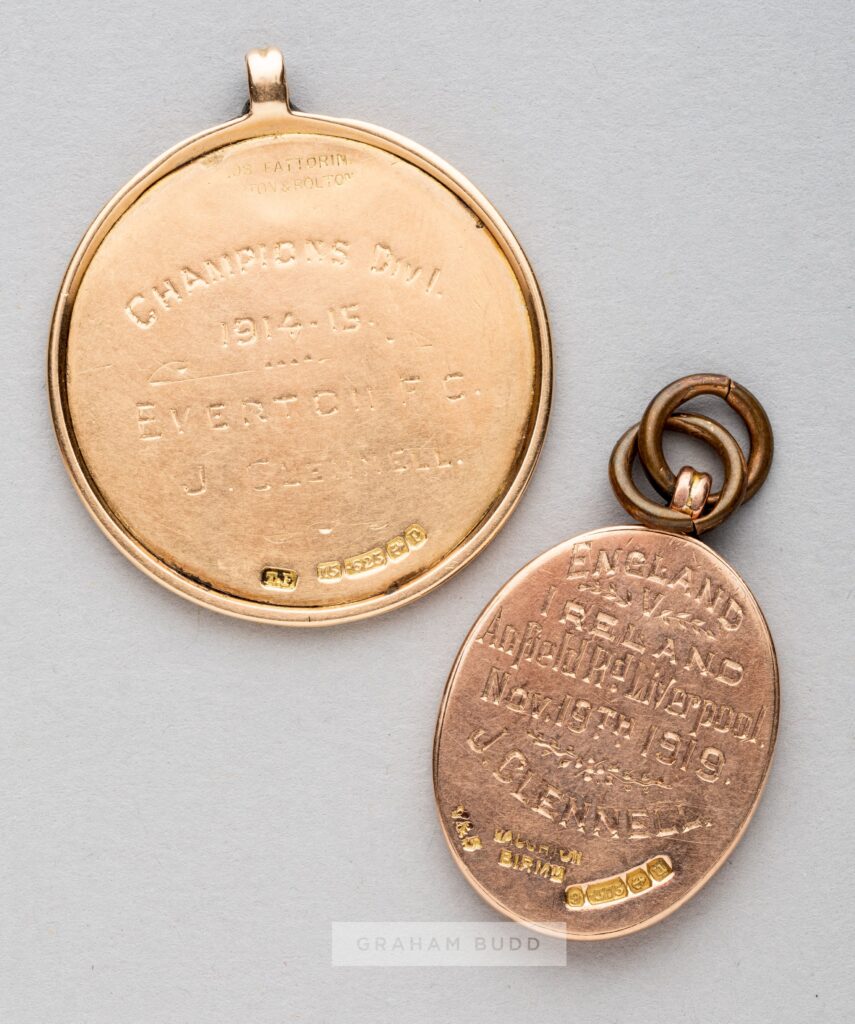

He featured in Rovers’ final three matches of the 1910/11 season, getting a brace against Middlesbrough on the last day. Come the 1911/12 season, 18 league appearances at inside-left yielded nine goals earning Joe a Football League Championship medal – the first time the East Lancs club had finished at the head of the table. The title was sealed with a home victory over West Bromwich Albion, with Joe grabbing two of the goals. 12 days earlier, Joe had scored two of Blackburn’s goals in a key 3-1 win at Goodison Park. Their total of 49 points was three clear of Everton, in the runner’s up spot. Soon after wrapping up the title, Joe and his Rovers colleagues headed to Belfast to take part in a charity match in aid of the Titanic Disaster Fund.

From the high of becoming a Football League champion, Joe was brought down to earth with a bump when injured in the opening fixture of the 1912/13 season, against The Wednesday. Having displaced a cartilage in his right knee, he did not feature in the first team for the rest of the season, merely getting some reserve team football from March onwards. This was the first of a number of knee injuries that plagued him. Remarkably, in an era in which knee surgery was rudimentary, it did not truncate his career.

He was fit enough to travel with the squad for a post-season programme of matches in what was then Austro-Hungary, Sunderland making the same trip. The match against a local side in Budapest (possibly Ferencváros) was an eye opener for Joe as to the volatility that could be experienced in football in mainland Europe. Some years later, he reflected:

‘Against their kick and run and hug and push game we were soon masters, being three goals to the good. The crowd was flabbergasted and the Austrian players were in a worse state. Enter the rough element, forthwith. Suddenly, without a word of warning – or justification, I may add – someone came along and threw me headlong to the floor. Our half-backs rushed up and a scene was the result. We were ‘talking foreign’ to the Austrians – and vice versa – and bedlam reigned. Chaos was the order.’

Although available for selection as the 1913/14 campaign got underway, Joe could not displace England-capped Eddie Latheron from Rovers the first team, instead showing prolific form (24 goals) in the reserves. When given an opportunity with the first team in the autumn, three of his four appearances were in a less-favoured central attacking role. Everton were waiting in the wings.

In fact, the Toffees had sought to secure Joe’ s services as far back as November 1910, just months into his tenure at Bloomfield Road. At that point, a £250 offer had not seduced the seaside club. A further attempt by the Blues in March 1911 failed when Blackpool quoted a £1,000 fee on the prized asset’s head, having already rebuffed an offer of £800 from another suitor. Everton demurred; they did, however, at this time press ahead with the £750 signing of Frank Jefferis to operate at insight-right.

In October 1911, having turned their attentions to Latheron, and been knocked back again by Blackburn, the Toffees directorate once more tried to capture Joe, putting in a lowball £700 offer. The chairman and Will Cuff headed to Ewood for talks, but need not have bothered, as the club’s board minutes record:

Clennell etc: The Chairman reported his & the Secretary’s visit to Blackburn & that club would not part with any players.

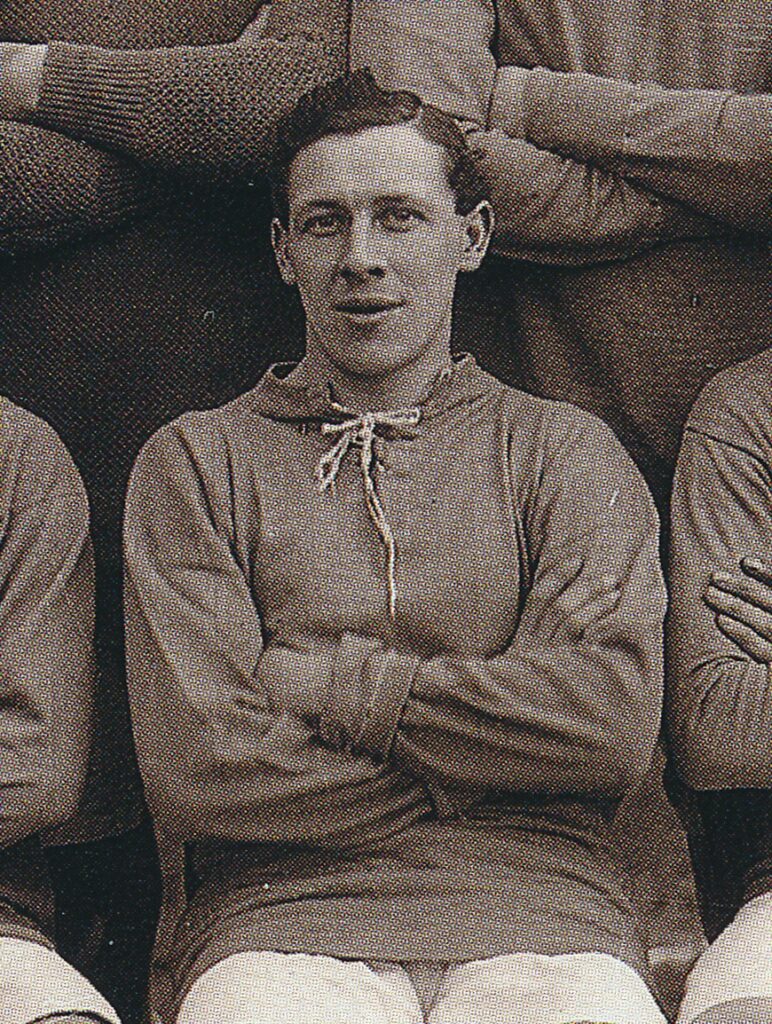

(photo: Brendan Connolly Collection)

And that, it appeared, was that on the Clennell front. However, the Blues’ interest in the man from New Silksworth was never quite extinguished. Director John Fare had been impressed by the inside-left in a Burnley versus Rovers match in late 1913, so Will Cuff was given authority to try to negotiate a transfer for up to £1,200. The Blackburn board informed the Everton secretary that they would not budge on a £1,500 asking price, so, after some quick-fire messaging amongst the Goodison directorate, Cuff was instructed to agree to Blackburn’s terms and get the deal sealed. Joe would receive a signing bonus of £10 and £4 per week wages. The following clause about a long service award (referred to as a ‘benefit’) was also included in the contract:

Provided that if the player shall by his conduct and ability satisfy the Club then and in such case the Club will during the fifth season from the date of this agreement grant a benefit to the player.

Joe also included a stipulation that he be allowed to continue living in Blackpool until such time had married Katherine ‘Kitty’ Turner, who hailed from the Fylde coast, in the close season.

One newspaper reported:

The transfer has come as a great surprise to Blackburn supporters, for although he has stood down from the premier eleven, it was never thought the Rovers would part with him. He is a popular player, a magnificent fine shot, and an opportunist.

A day after signing, Joe lined up in his preferred inside-left position at Goodison Park against Aston Villa on 24 January 1914. It came as a shock to Frank Bradshaw, who walked into the changing room, only to find Joe ensconced at his ‘peg’. No-one had thought to pre-advise the incumbent inside-left. Once that moment of awkwardness was put aside, Joe got off to a dream start for his new club by scoring with practically his first kick of the ball, converting a cross from Bill Palmer. Although the Toffees eventually fell to a disappointing 4-1 home defeat to Villa, the Liverpool Courier praised the new recruit, who was showing early signs of developing a good understanding with winger George Harrison:

Barber and Lyons proved quite incapable of holding Harrison. The left winger, who received many clever passes from his new partner, Clennell made a succession of clever sprints, and the pity of it was that his well-placed centres were not utilised to better advantage. Clennell is on the small side, but he is not without skill, and apart from the goal he scored, he gave Hardy several warm shots to stop.

This snippet summed up Joe’s trademark play well, relatively stocky at somewhere in the region of 5’6” (reports of his height varied) and 11st 4lb, Joe possessed a low centre of gravity which, combined with his excellent touch and strength, made him hard to knock off the ball. Furthermore, he was an advocate of getting a shot away, in the knowledge that he might beat the goalkeeper or force a rebound for a teammate to tuck away. Hints of a young Wayne Rooney in style, perhaps.

His away debut was in a friendly match against Woolwich Arsenal, a 2-1 win for the Toffees, with the Liverpool Courier noting: ‘Harrison and Clennell were the clever wing pair, Clennell delighting the crowd with his trickiness.’ His precision shooting was soon being commented on in the press, as evidenced by the reaction to a brace against Sheffield United in mid-February. He was immediately a shoo-in in the ‘number 10’ role for the rest of the season, but inconsistency by the team was reflected in a decidedly poor 15th place finish. Perhaps, he reflected ruefully on his former club, Blackburn lifting its second championship title in three years. The summer saw Joe marrying Kitty as planned, and showing himself to be a useful batsman when turning out for Blackpool Cricket Club.

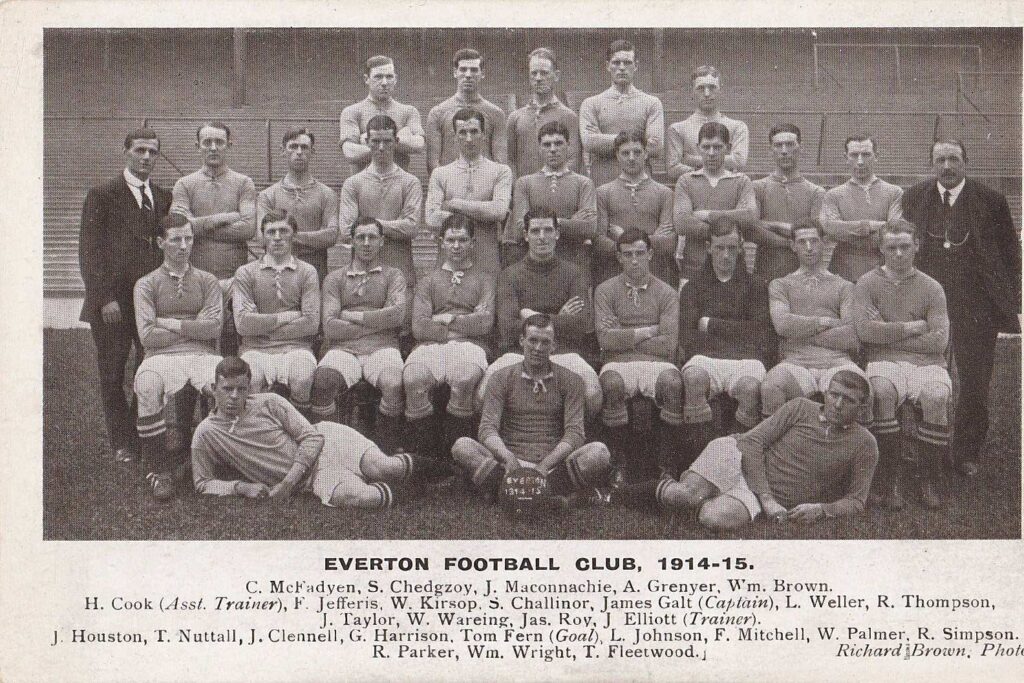

The forward line of Chedgzoy, Jefferis, Parker, Clennell and Harrison was unchanged at the start of Joe’s first full season as a Toffeeman. One key addition to the team was half-back James Galt, a signing from Rangers, who immediately improved the organisation of the team in his role as captain. For the Blues and Joe, the 1914/15 season couldn’t have got off to a better start – a 3-1 win at White Hart Lane thanks to a hat-trick by the inside-left. The Liverpool Courier told the story of a day of triumph for Joe Clennell and his teammates:

Clennell was the man of the moment with a hat trick performance that was full of merit. The equalising goal came twelve minutes after the restart, when fastening on a short pass from Harrison, Clennell dribbled through and shot a great goal. Three minutes later he repeated the performance, while ten minutes from the end, Jaques, the new Spurs’ custodian, was beaten a third time. The Everton team at the start was not convincing, but once they had settled down, they made the Spurs appear a very moderate team. The chief point about Everton’s superiority was their quickness in making an attack. Harrison and Clennell on the left wing were splendid. They combined beautifully, and both had a lot too much pace for Weir and Clay, the defenders.

In all, Joe would find the back of the net 17 times that season (14 in the league and 3 in the FA Cup), none was more important than in the penultimate match of the season, as Everton and Manchester City battled it out to try to overhaul title favourites Oldham Athletic. Joe scored the decisive goal of the game at Hyde Road, reacting first to steer home the rebound after prolific Scot Bobby Parker had forced the City goalkeeper into a save.

Two home defeats at the death for Oldham effectively gifted the Blues the title, a 2-2 draw with Chelsea edging the Blues a point ahead of Latics on the final day (although they would have been champions on goal average, regardless). Thus, Joe, at the age of 26, collected a Football League Championship medal for the second time. The first day of May 1915 must have erased all the elation Joe felt as a newly crowned Football League champion when his wife Kitty passed away in her 26th year, after less than a year of marriage. It is reasonable to conclude that her death was linked to complications in giving birth to her son, Frederick.

Regular football competitions were suspended for the 1915/16 season, in light of the ongoing war, and player’s contracts were not renewed. Joe would get employment working in the transport section at Liverpool’s docks, but made himself available to play for Everton when those commitments permitted. In a pre-Lancashire War League season trial match for his club, he gave a statement of intent when scoring four. The Liverpool Courier reported:

Clennell was in rampant mood, and the little man highly enjoyed his shooting which was of the most forceful and deadly character. He sent the ball in with rare string, and the crowd relished his accurate marksmanship. Clennell was again the leading figure, and the crowd expressed their delight when he banged in shot after shot. One or two of his drives hit the backs and the defenders afterwards showed a desire to get out of the way when Clennell prepared to shoot

Joe carried this form into the season, starting with a drubbing of Bury in which he turned on the style to amuse and delight the crowd, if not the opponents. The Liverpool Echo recorded:

There was evidence that some of the players wanted to find time for a little jugglery for the crowd’s benefit, and most noticeable in this respect were the tricks of Joseph Clennell and the latter approached the touchline toying with the ball…Clennell throughout was in jovial mood, and by pretence to pass or kick or shoot made himself most popular with the crowd.

In contrast to the smile on the pitch was the tragic news of the death of his only child, Frederick, as reported in the Echo on 9 September. He would have been four months old, and died in Sunderland, presumably in the care of Joe’s mother or one of his siblings. After missing just one match in the wake of the bereavement, Joe was throwing himself back into his football, scoring in a win at Old Trafford.

As he was never called up for active service, on account of his docks occupation being considered vital to the war effort, and based on Merseyside, Joe racked up 124 appearances in the four wartime league seasons (second only to Bill Wareing on 127, and closely followed by Tom Fleetwood on 121 and fellow North Easterner Alan Grenyer on 119). The variety in quality of opposition and his propensity to have an accurate shot at goal helped him reach a jaw-dropping tally of 124 goals. He also found time for cricket in the summer, joining the ranks at Bootle Cricket Club in 1916. According to the Sporting Chronicle, in one match in his first season there, his score of 48 made him ‘quite the idol of the crowd.’ A teammate was Bert Sharp, a former Everton full-back and brother of the more famous Jack Sharp.

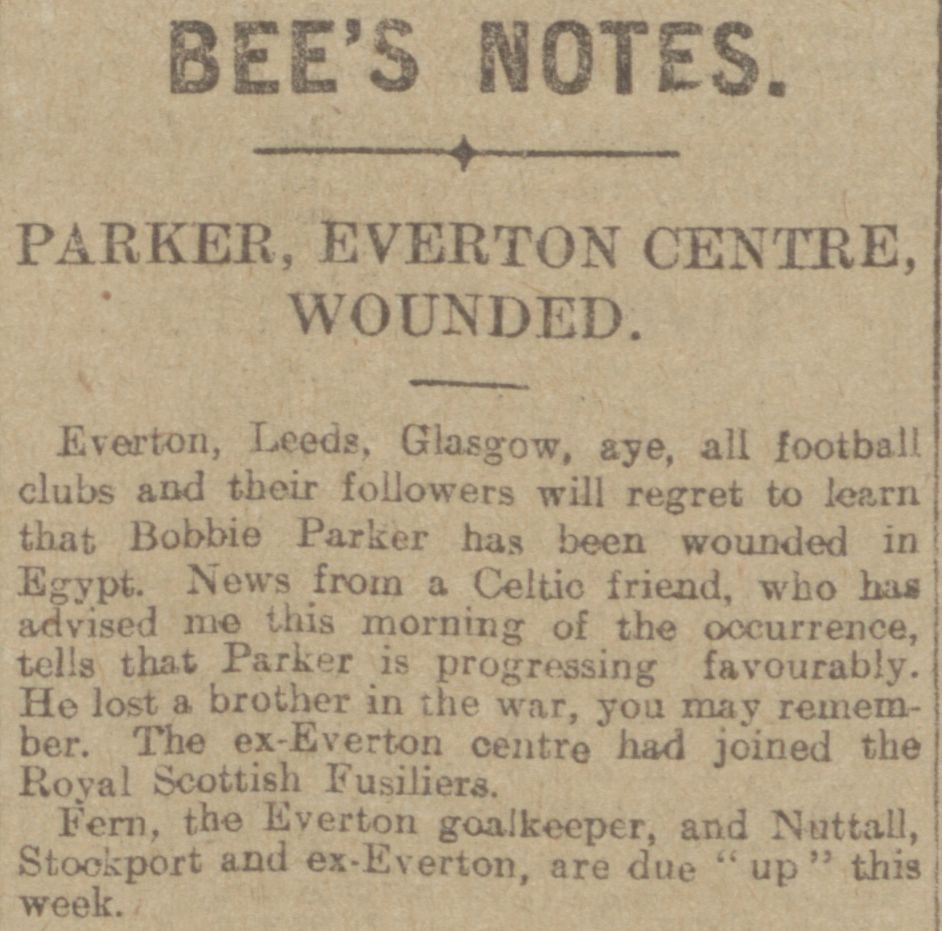

Although none of the Everton first team regulars were killed while serving their country, Bobby Parker sustained serious shrapnel wounds in the spring of 1917. A few months later, Eddie Latheron, the great Blackburn Rovers forward who had kept Joe out of the team, was killed at the Battle of Passchendaele, aged just 29.

Had it not been for the war and his cartilage issues, there is every reason to believe that Joe would have been recognised at international level. As it was, the closest he came was the Victory international match between the Football League and Scottish League at Birmingham in February 1919. He graced the occasion with a superb goal. He was also selected for a Football league representative side which played at Anfield against the Irish League team in November of the same year. 1919 also saw Joe marry for the second time; he tied the knot with Eileen Jones from Aintree. A crowd of youngsters gathered outside Stuart Road church to wish the newlyweds well.

When the Football League competition resumed in the autumn of 1919, Everton could call on the majority of their title winning 1914/15 squad, albeit a side having lost four years of top-class football. The major absentee was captain James Galt who was affected by PTSD from his experiences on military service and was not able to return to the football fray at a high level. Injured in pre-season, Joe was not fit to make the first eleven until a 2-5 home reverse to West Brom, albeit he was singled out for some praise in the Daily Post and Mercury: ‘Clennell’s return added strength to the line, and he worked vigorously to infuse life into the attack.’

Without the inspirational Galt, and having the returning Bobby Parker being a shadow of his former self, the Toffees endured a disappointing season, the reigning champions finishing in a distant 16th place. Joe had struggled with a knee strain over the festive period and, when recalled to the side for a trip to Aston Villa on Valentine’s Day, had to be carried from the field after his knee gave way after a collision with an opponent. He bravely, and probably ill-advisedly, re-entered the fray after receiving treatment, helping his side to a 2-2- draw. Just before full-time, he collapsed again and had to be carried off once more – signalling the end of his involvement in the match and the season.

After some rest, the specialist inspecting Joe’s leg in late March reported to the Everton board that surgery was required, with the knee going under the knife in mid-April. He was reportedly ‘fully recovered’ as the two pre-season trial matches approached in mid-August but promptly suffered further damage to his other knee. Bee, in the Echo, predicted a three-month absence for the stricken forward.

Based on Dr. McMurray’s assessment, Joe underwent further surgery on the damaged cartilage in late August. Back in training in early November, he returned to action with the second string on the 27th of that month. He threw himself into the match but it was quickly apparent that a loose piece of cartilage in his knee was troubling him and the Echo relayed the news that yet more surgery was required. He entered hospital on 6 December in anticipation of the removal of cartilage of his right knee.

Having come through a reserve team outing in early March 1921, he was recalled to the first team for the trip to Spurs, as was his old partner Bobby Parker. Try as hard as he might, he could not prevent a 2-0 defeat and was described by Athletic News as a long way below his best self.

He returned to the reserve team and in a 4-0 defeat of Liverpool in the Senior Cup was described bluntly by the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury item: ‘Clennell, who has put on a lot of weight, is still a skilled schemer and his penalty shots landed into the net but before Scott had touched each one.’

Rested after the summer, the 32-year-old impressed in trial matches for the 1921/22 season as the Daily Post and Mercury match report detailed:

Clennell also took upon himself some hefty drives which Fern did well to handle in a confident manner, without blurring his clearances. Clennell still kicks the ball very direct, with a slight swerve motion, and his passing is to the right man at the right time. He seems to have come right back to his best style of attack.

However he was overlooked for first team duty as the season got underway. When he did return to the fray, against Manchester United in early September, the Athletic News reported that he was some way off his peak form:

The reappearance of Clennell was satisfactory up to a point in that he did his utmost to set George Harrison moving, but he did not dart in at close quarters. Nor did he wheel and shoot from any angle as he used to do. Both Clennell and Fazackerley relied too much on the one style of game. There was no variation, no individual trustfulness, and no long passes to the other wings.

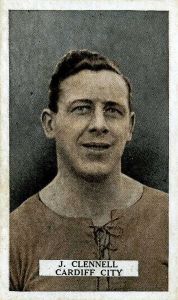

Sensing that Joe, with age and knee problems against him, Joe was on the downward trajectory, on 11 October 1921 it was resolved by the board that the club secretary would write to other clubs, stating that they’d consider offers – not only for Joe, but also Alan Grenyer and Louis Weller. Within a week, Cardiff City responded regarding Joe and terms were agreed. The £1,500 fee would be paid in two instalments. Joe, who was by this point also a licensed victualler, living at 14 Barlow Lane, Walton (the other side of County Road from Goodison Park and Spellow Lane, prior to that he had lived at 492 Rice Lane), agreed to the transfer on condition he could live on Merseyside and commute down to South Wales for matches. Joe was also awarded his pro-rata accrued benefit.

Bidding the popular forward a fond farewell, the Liverpool Echo declared:

He learned his football up north, Shields way, and has been one of the most popular of players, because he was tricky, could shoot like a gun, and was always clean on and off the field. He suffered wretched luck through operations to the knee, and probably no man has ever suffered such tortures through sheer misfortune. However, this lesson he has shown that he was still a power in the forward line, and as Cardiff have been losing matches through inability to get goals they went far and near to strengthen that line, and have done a wise stroke of business in getting a man who can and will shoot. All Liverpool sportsmen will wish the little ‘rover’ a good luck with his new club.

Bee, in the Football Echo wrote:

The news of Clennell’s signing for Cardiff City…was no great surprise to the followers of the club. Clennell was immensely popular with us – he was clean in every movement, and on and off the field made many friends. I mind the time when he played with Alan Grenyer for the English League team in the Midlands, and a famed Scottish expert said ‘Clennell is just wonderful. He would suit our best Scottish clubs.’

Athletic News, meanwhile, paid this tribute:

There is no doubt that Clennell at his best is a rare player. Possessing the use of either foot, he is a clever dribbler and a sure marksman. He has, however, been unfortunate, having experienced serious trouble with the cartilages of both knees. Cardiff City have no doubt satisfied themselves that he is sound again. Clennell is such a fine all-round sportsman that he will take from Liverpool the best of wishes from a large number of enthusiasts who have admired his whole-hearted and clean play.

Cardiff did subsequently approach the Toffees directorate about the possibility of their forward training at Goodison Park in midweek. The board minutes record:

Clennell: An application from Cardiff City FC for permission for this player to train on our ground was not entertained.

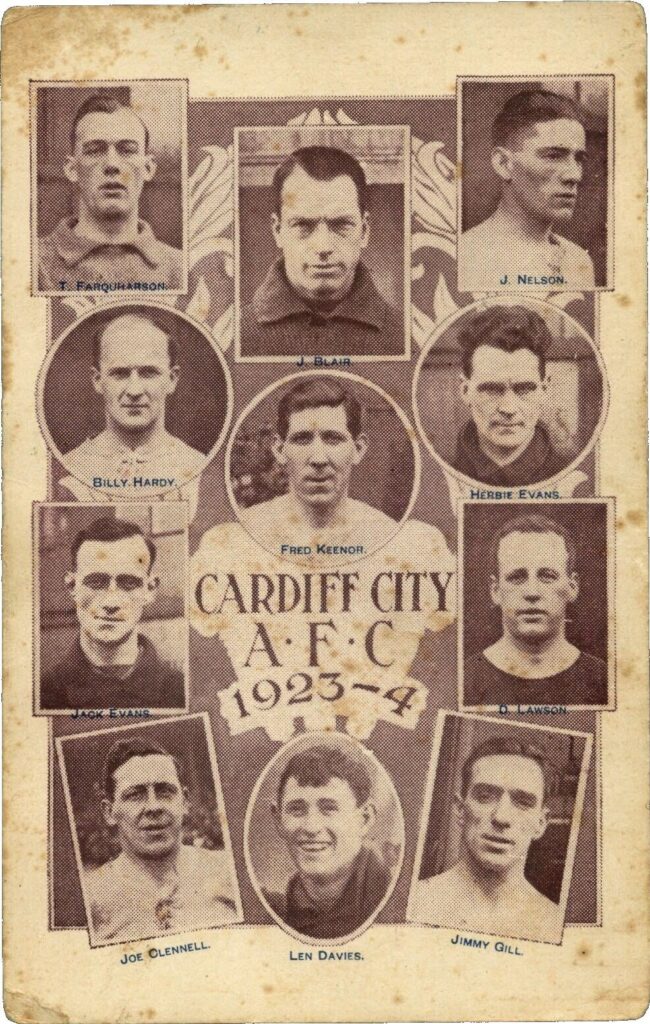

It is unclear where Joe did train on Merseyside, but come the start of 1924, he moved, lock stock and barrel, to Cardiff, taking on the tenancy of the Robin Hood pub on Severn Road in the Canton district. Subsequently he ran the Lansdowne Hotel and it was from here that the Joe Clennell Cup Race – presumably he provided the silverware – would be run annually. The nine-and-a-half-mile cross-country race started and ended at the hotel, which was no doubt willing and able to offer refreshments to the competitors.

Anyone thinking that Joe would gently wind down his playing career in moving to the Welsh capital city was sorely mistaken. He made an immediate, positive impact for the Ninian Park outfit. He may have been quite as prolific in front of goal for his new employers (although he hit double figures in three consecutive seasons) his scheming and nous were a boon. He would joke with his teammate, Fred Keenor – who rated Joe was one of the finest inside-forwards Cardiff had ever had, about his lack of cartilage and, tongue in cheek, suggest that all professionals should have their cartilages removed before embarking on their career.

Whilst in Cardiff’s employ, he produced a syndicated newspaper piece in which he underlined that, although recognising victories were of paramount importance, players had a requirement to entertain those coming through the turnstiles to the best of their abilities:

It seems to me that the player should bear in mind that the onlookers have their rights: they have paid to be entertained, perhaps, and it is always up to us to provide the onlookers with the best possible entertainment.

The Bluebirds won the Welsh Cup in both 1922 and 1923 and the following season saw Cardiff push Huddersfield Town, managed by Herbert Chapman, all the way in the title race. Tying on 75 points, the Terriers edged it on goal average, robbing Joe of a championship medal with a third club by the narrowest of margins (1.818 vs 1.794).

Having started the 1924/5 season in his habitual inside-left role for Cardiff, the autumn saw him miss matches due to further knee compliant flare ups. He was back in contention in early February, telling Thomson’s Weekly News:

It is thought in some quarters that my playing days are over. But I would like to say that I feel pretty confident of getting back into the limelight again. My knee troubles have disappeared. I have stood the test very well in the reserves recently, although the heavy grounds have been, naturally, rather trying. All the same, I am very hopeful about the future.

Joe was now entering the peripatetic stage common to many footballers’ careers. Like a fair proportion of veterans who wanted to keep playing for as long as possible, he would change clubs regularly, with a ‘have boots, will travel’ mentality. Come February 1925, he informed the Bluebirds that for personal reasons (not shared in the public domain) he wanted to return to live in the Blackpool area. Cardiff reluctantly agreed and made him available to transfer. When Stoke City’s manager, Mr. Mather – who was after an experienced forward – got wind of Joe perhaps returning to his first League club, he stepped in and persuaded the veteran to sign for the Potterson the proviso that he could commute from Blackpool. In leaving Cardiff, Joe missed out on potential appearing in an FA Cup final, the Bluebirds losing to Sheffield United on 25 April.

The stay at the Victoria Ground lasted 15 months and ended in the club’s relegation from the Econ Division. Having made 35 appearances for the Potters, he once more headed south west, to join Bristol Rovers of Third Division South in the summer of 1926; come March the following year he took on the running of the Ship Inn public house at No. 1 Cathay, in the Redcliffe district of the city (the 18th Century building is still home to a pub, to this day). In an age of tightly controlled licensing hours, it appears that Joe took a more liberal approach and was not averse to providing a ‘lock-in’ – as evidenced by the fine he received for ‘supplying intoxicants during prohibited hours. After one season, his time with the Pirates was at an end. He placed a listing in Athletic News in late September 1927, stating that he was open for engagement as a player or player-coach. Within a couple of weeks, he was once more bound for Lancashire, joining Rochdale FC. It was stated that he also hoped to settle in the area and run a business (most likely, a pub).

In his first appearance for the Dale reserves, against Bradford, it was declared that he showed ‘capital form’ he went on to make 15 appearances for the Spotland outfit in Division Three North and FA Cup matches. However, in March 1928, he was released by Rochdale, returning to South Wales in order to become Mine Host at the Junction Hotel at Taff’s Well, a village located between Cardiff and Pontypridd.

A year shy of his 40th birthday, the publican agreed to turn out for Ebbw Vale of the Welsh League. His wife Eileen made the local press in August when she appeared at Cardiff County Court having allegedly driven her car into a greengrocer’s parked vehicle which had been laden with fruit and vegetables. According to Mr. Pring, the plaintiff, Mrs. Clennell had been driving at dangerous speed and her vehicle had made a violent impact with his, throwing his produce into the road. Mrs. Clennell disputed the assertion about her driving style and stated: ‘The only vegetables I saw were about five tomatoes in the road.’ Mr. Pring’s claim for £28 damages was allowed.

From Ebbw Vale, Joe moved on to a brief stint with Barry before his footballing journey took him across the Irish Sea in 1929, when appointed player-coach of Bangor. He got off to a dream start, scoring the winner on his debut, against Belfast Celtic. Hamstrung by disappointing gates, which hit revenue badly, Joe led Bangor to an equal-fourth place finish in the Irish League and a Gold Cup Final, which they lost to Distillery. At the AGM, held at the end of the season, fulsome tribute was paid to the coach but this appears not to have signaled Joe’s engagement for a further 12 months. Instead, he remained in Northern Ireland as the reserve team coach of Distillery. While turning out for them, he suffered a dislocated collar bone and elbow, which may have brought his playing days nearer to an end.

In no time, he was back in Lancashire, running the Duke of Edinburgh pub in Blackburn and turning out for Great Harwood FC. Even at the age of 42, he was reported to be pulling on the strings as prime attacking instigator. It seems that the censure he had received for selling alcohol outside of permitted hours in Bristol had not deterred him from doing likewise in Lancashire. Twice in 1931 he was fined for selling intoxicating liquor when it was against licensing laws to do so. It appears that, having been fined 20s and then £5, he belatedly learned his lesson.

After a hiatus, Joe re-entered football when appointed coach of Accrington Stanley in the summer of 1934. It was a pretty dismal season, with the club struggling to an 18th place finish in the Third Division North. Joe then left as the club as it chose to bring in a de-facto manager. In March 1936, the former football star was granted a temporary license to be landlord of the Bird In Hand in Haslingden (Rossendale), holding it until July 1937. While in Haslingden he was either involved with the town’s non-league football club or, at the very least, kept an eye on their games. He recommended John Arthur, the 18-year-old forward, to his old club, Everton. They had him over to Merseyside and signed him on professional forms in September 1936. The Everton board minutes make reference to subsequently receiving a letter from Joe. Perhaps he was requesting a ‘finder’s fee’. The minutes recorded: J. Clennell: Letter read from this ex-player but no action taken.

1939 saw the end of the Clennells’ marriage, with Joe being granted a decree nisi at Manchester Assizes. It appears that their daughter, called Eileen, like her mother, remained with Joe in Blackpool until she married a Lt Bishop in 1941 and had a son, Ian. The 1939 Register, taken shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, had Joe living with his daughter in a modest terraced house at 61 Bedford Road, Blackpool, a few minutes’ walk from Blackpool North railway station. Eileen gave her occupation as a chemist’s assistant while Joe was recorded as being a cellarman. Joe had, by now, stepped away from football as a profession, although he did a spot of scouting for his first professional club and now near neighbours, Blackpool FC. His primary income until he retired came from employment by the Civil Service, which had a significant presence in the area.

By the 1960s Joe was living on Holly Road on North Shore. It was close his home, while crossing Warbreck Hill Road on the evening of 28 February 1965, that he was knocked down by a car. The 76-year-old was rushed by ambulance to Blackpool Victoria hospital but was declared dead on arrival, the result of a fractured neck. At the subsequent inquest, the coroner put the death down to misadventure with no blame attached to Mr. Harry Cox, the car’s driver. The funeral was held at nearby Carleton. Several of Joe’s footballing contemporaries were in attendance and the wreaths included one with blue and white silk ribbons, sent by the directors and players of Blackburn Rovers.

Since Joe’s time in a royal blue shirt, Evertonians have been lucky to see the likes of Tommy Johnson, Alex Stevenson, Wally Fielding and Roy Vernon operate as a scheming and scoring inside-lefts, but Joe Clennell, as this article hopefully establishes, bears comparison with the best of them.

Postscript

12-year-old Gary Flintoff, now BBC Radio Sport’s England Football Producer, did a double-take when his grandmother mentioned in passing that a relative of his had once been a professional footballer. The sports fan’s curiosity was piqued and he set out on a voyage of discovery about his ancestor. What struck him were the many similarities their movements over the years. Gary, too, had moved from the North East to the Fylde Coast. Later, he had covered Blackburn Rovers for BBC Lancashire, before transferring to Liverpool when working for BBC Radio Merseyside. I am grateful to Gary for sharing cuttings about Joe that he obtained some years ago.

Sources

Various newspapers (Merseyside, Lancashire, South Wales, Ireland and Somerset)

Corbett, James, The Everton Encyclopedia

Orr, George, Everton Football Club: Champions 1914-15 ‘Over The Top’

Keates, Thomas, History of the Everton Football Club, 1878-1928 (1929)

Johnson, Steve, evertonresults.com

Smith, Billy bluecorrespondent.co.uk

The Everton Collection evertoncollection.org.uk

The English National Football Archive. enfa.co.uk

Doing the 92 doingthe92.com

Gary Flintoff

1914/15 squad photo care of Brendan Connolly