I was in touch with The former Rugby Union star Tom Smith, some months ago when I discovered that sporting excellence runs in his family. His great-grandfather was John Bell (often referred to as Jack Bell) – one of the brightest Association Football stars of the 1890s, who left an indelible mark at Dumbarton, Everton, Celtic, Preston North End and on the Scottish national team. There was more to the teetotal, moustachioed Bell than his activities on the field of play. He was a pioneer of the unionisation movement in football – a stance which won him few friends in the higher echelons of the game.

John Watson Bell was born in Dumbarton – located on the north banks of the River Clyde, 20 miles downstream from Glasgow – on 6 October 1868. His father, James was a butcher; the family lived at Croft Lead and then moved to 121 High Street. After a season playing for Dumbarton Union John switched allegiance to local rivals Dumbarton FC – The Sons of the Rock, as they are commonly known.

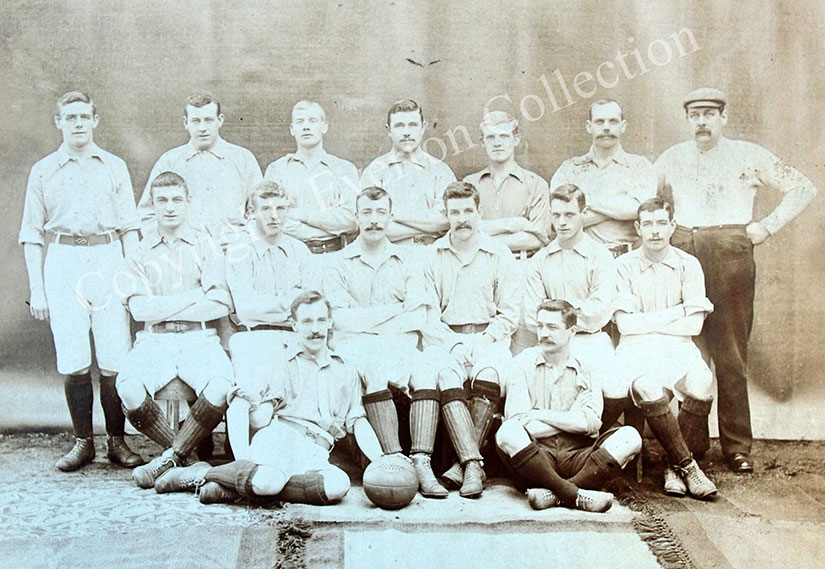

Evertonians may primarily associate Dumbarton FC with Graeme Sharp, who came down from there to Merseyside in 1980. However 90 years previously, the club was a hot-bed of talent, and for a glorious, yet brief, period, it was the best team in the land. The 1891 Scottish League title was shared with Glasgow Rangers (after a play-off ended in a draw) and, a year later, it was won outright.

Bell’s appearance was striking: at just shy of 6ft and 12st. 7lb. in weight, he was totally unlike the stereotype of the dinky Scottish winger. His appearances for The Sons – which saw him score 62 times in 78 appearances – earned him a senior Scotland call-up in March, the first of 11 for his national team over a decade.

The staunchly amateur club’s team began to break up as English professional outfits poached their best players with lucrative offers. Alex Latta had moved to Everton in 1889 and more would follow. John was one of the most coveted players in Scotland, so it came as little surprise when the Everton Committee dispatched Alex Latta and the Club Secretary to try to close a deal. Terms of up to £3 per week, a £10 signing-on bonus and 10/- for a win were presented. However, John was not persuaded that the time was right to relocate. He felt a sense of loyalty to Dumbarton and was also progressing well in his employment as an engineer at a local shipyard. Teammate and close friend Dickie Boyle was lured to Goodison Park that summer and this gradually eroded John’s resolve to remain a Son of the Rock.

In March 1893 – Immediately in the wake of the FA Cup Final defeat to Wolves (staged at the ill-equipped Fallowfield) – Everton made renewed efforts to lure the Scot. Mr Griffiths travelled north once again and, this time, terms of £4 per week were agreed (with a bonus of £10 and an advance on wages of £20 with 20/- to be repaid per week). John’s teammate at Boghead Park, Abe Hartley, had joined the Toffees a few days previously.

Having watched from the Everton Directors’ Box on Good Friday, the big signing was straight into the team against Bolton Wanderers on Easter Monday. He debuted at inside-right forward – he actually preferred the inside-left position but spent much of his career excelling on either wing. The following season saw England striker Jack Southworth added to the squad as the Toffees spent big in the search for a second League title (to follow that won in 1891). John would notch his first goal for his new club in the fourth match of the season – a 4-2 defeat of Aston Villa. A broken collar bone ended a first full campaign prematurely but his ten goals in 25 appearances gave great grounds for optimism.

Fit again for the 1894/95 season, he found himself played on the left flank – occasionally being moved to more central positions. A 20 goal-haul in 30 appearances was quite remarkable in the circumstances. October of that season saw the staging of the first League derby between Everton and their recently-formed rivals from Anfield. 44,000 were present at Goodison to witness a fiercely-contested affair. Alex Hannah – the one-time Everton captain who was, by now, leading the Reds – crudely injured John as he flew down the left wing but he soldiered on. His reward was Everton’s third goal (‘’breasted into the net’ according to the Liverpool Mercury report) in a 3-0 win.

Sadly, a dip in form in the spring of 1895 saw Everton finish the season in second place, five points behind Sunderland. This disappointment aside, John continued in a rich vein of scoring form – irrespective of where in the forward line he was played. In April 1897 the club earned an opportunity for redemption for 1893’s Cup Final near-miss by reaching it again. This time it was staged in the far more suitable Crystal Palace ground with Aston Villa the opponents. The match would be hailed as the finest final in the competition’s history, at that point. In blustery conditions John (now joined in the team by ex-Dumbarton ally, Jack Taylor) gave one of his greatest performances for the Toffees – continually running at the Villa defence – exhibiting strength, speed and skill on the ball. His goal was described in the Liverpool Mercury:

Bell using his speed to splendid effect got past the Villa backs almost before they knew where they were. Whitehouse, seeing a goal as inevitable, ran out but just before he could reach the ball, Bell, with fine judgment, tipped it past him. Then, having nobody else to face, easily put the ball into the net – being greeted with vociferous cheers.

The Herculean efforts of Bell and his Everton teammates were not enough as Villa edged the tie 3-2 (due, in part, to goalkeeping errors). Even in defeat John was named man of the match from a poll held of spectators. The Merseysiders would have to wait a further nine years to break the FA Cup duck – Jack Taylor would still be there to lift the trophy but John had, by then, moved on. After the heartbreak in South London, John rounded off the season with six goals in four games – including a first hat-trick for Everton.

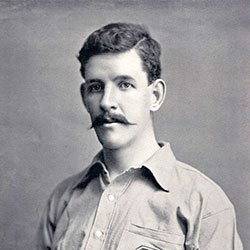

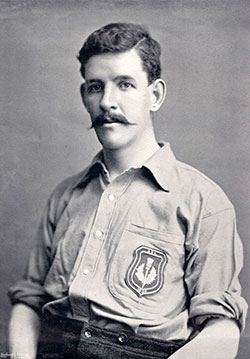

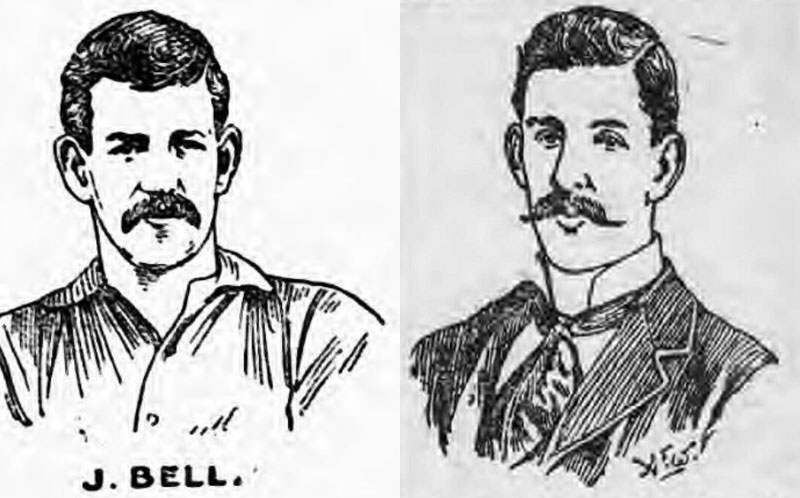

John Bell from the Sporting Life (left) and Lloyds Weekly News (right)

In the Victorian era it was rare for Anglo-Scots (i.e. those plying their trade in the English League) to gain international recognition – this makes John’s three Scottish appearances whilst residing in Liverpool all the more significant. He holds the proud status of being Everton’s first Scottish international. Some years later, an article described his style:

Of Jack Bell’s play as a forward much might be written in superlatives, yet to the present generation it would be of greater advantage to give some little pen-picture that would more aptly describe his style. Imagine him them, tall, broad-shoulders, narrow in girth, and firm, and well-set on limbs admirably propositioned…Fast in movement with gait that was deceptive in its real form of “speed when occasions demanded”. The dominating characteristic of his play was forcefulness – not roughness, be it understood, but simply a forceful determination to get through – rather than round – the opposing forces. His method of play to the uninitiated would savour of ungainliness until one realized that behind each feint or apparently lumbering stride, there was a clear cut definition of an opening to be made or a passage to be forced.’

His physical gifts and raw courage meant that he was able to withstand the treatment dished out by opposition full-backs and half-backs. A Lloyd’s Weekly News report from 1897 was a paean to the forward:

‘A forward of exceptional excellence, he, for a time, worked on the left wing, but he has gained his fame as a right wing player, where he enjoys the assistance of another Dumbarton man, Jack Taylor, and these two understand each other’s methods so well that they certainly form one of the most formidable combinations for attack possessed by any club in the country. Very neat in his work, Bell is an uncommonly good shot, and plays with a marked intelligence.’

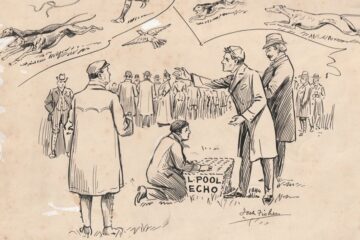

His robustness was gloriously illustrated in an account given in 1924 in Victor Hall’s ‘Famous Old Timers’ article for the Liverpool Echo about how John could take care of himself, when opponents resorted to agricultural techniques:

He met fair play with fair play; but when he met an opposition that was inclined to baser methods, he, too, was prepared to give force for force. Once, in a league match of great import, the centre-half opposed to Bell early on in the game gave clear evidence that he was more disposed to “play the man” than “play the ball”. Whenever Bell was in possession… the centre-half threw himself at him repeatedly. His knee was often raised dangerously in tackles without need; wild lunges were made that threatened serious injury to the player…and with a hesitating referee matters between the two players were approaching a crisis.

Then Bell, once more getting possession, started at a great pace with a clear run for goal – the half-back waiting for Bell’s approach. It was a duel as to who should succeed – the waiting half-back or the striding forward. As they met Bell tipped the ball twenty yards ahead, past the back, and then met him in full charge, half turning for the clash, so that he “took” the waiting player with his half-turned buttock across the chest shoulder high! Both men went down, of course – that was inevitable…But the charge was perfectly fair and only Bell arose unaided; nor did the opponent play much again in that match, or for many a day afterwards. He brought it on himself by his method of play, and those who played that day on both sides agreed that it was a choice of “Bell or the other fellow” to go down. Not many men playing them could say that they had ever “stopped Bell.”

In appeared, during the 1897 close-season that Everton had lost the services on their star forward. A schism had formed between player and committee members. Back in mid-April the minutes record that John would only be offered terms for the coming season ‘provided he apologise to the Directors for his insult.’ Clearly, John did not see fit to do so and was reported as having joined Glasgow Rangers on 15th May (the move back to Scotland probably coinciding with a business venture in the area). It seems that John then made a volte-face without kicking a ball for the Glasgwegians. In mid-June the Scottish press was speculating that he might make himself available for some ‘important’ Everton matches. Two months later, Everton’s committee agreed to re-engage him at £5 per week – on the proviso noted in the minute book that: ‘he apologises to the Directors for his conduct’.

A belated apology was duly made and he lined up for the 1897/98 season alongside his brother, Laurie, who had joined from Sheffield Wednesday. Thus, they became the first fraternal pairing to appear for Everton in the Football League (the Balmer Brothers would follow them in the following decade). The Blue Blood Brothers would appear 21 times together. The younger sibling made a dream debut, netting twice in a home win over Bolton Wanderers, but failed to make quite the same impression on Merseyside as John and moved on after two seasons as a Toffeeman.

One of the most remarkable tales concerning John was recounted in Thomas Keates’ golden jubilee (1928) history of the club. Having spotted an opposing player walking in circles in a dazed manner; John rushed over to him and took immediate action to adjust a dislocated neck – possibly saving the player’s life. Clearly, John was made of sterner stuff – another anecdote detailed how he was hit by a hackney cab on London’s Strand but dusted himself off and went on to play for his country in the international fixture staged at Crystal Palace the following day.

In 1898 John married Isabella Graham, whose Scottish parents lived on Beacon Lane, Everton (close to the library building). The couple went on to have three children (James Gordon, Muriel and Sheila) and seemed settled in the area. However, John’s time at Goodison was drawing to a close for reasons were far-removed from his form on the pitch. He and a number of other players had become active in the campaign against a weekly wage cap of £4 being introduced (top players could earn double that figure). This led to the formation of the first footballers’ trade union. Everton players were well-represented amongst the prime movers in the new movement. They included John Bell, Johnny Holt, John Cameron and David Storrier – plus the likes of Tom Bradshaw (Liverpool), Billy Meredith (Manchester City) and Abe Hartley (Liverpool and ex-Everton).

John was duly selected as chairman of the Association Footballers’ Union (AFU) on its official foundation in February 1898. Headquartered in Liverpool, it boasted 250 members and had a key policy that players should have an involvement in any negotiations regarding their possible transfer (rather than being excluded from talks between the clubs concerned). In March, an agreement was reached to amalgamate the AFU with a sister organisation in Scotland – and form the the National Association Football Players Union (NAFPU) with John as Chair. The body set about founding a provident fund for members and sought reform of contract rules. A union fundraising match between English and Scottish-based players was staged in April.

One can well-imagine that these union activities were viewed with dismay by the Everton Committee (and directors at other leading clubs). The Everton minute books record that in April, the club decided to dispense with John’s services at the season’s end. Committee member Dr. Baxter later argued for Bell’s retention but in vain. In fact, John had surprisingly announced in February that it was his intention to retire from football at the end of the season in order to start a business in Liverpool (he also intended to remain involved with the nascent union). In the midst of this activity, the Sporting Life produced a pen picture of the man in question:

‘A typical Scot in more ways than one. He loves his country but also has an eye to the main thing. More than one will tell you that he is the “cutest football player breathing”. He is a big handsome fellow, very gentlemanly, very reserved, a teetotaller. He is a player of the first rank….’

The defection of many union members to the wage cap-free Southern League (which included ambitious clubs like Tottenham Hotspur and Southampton) weakened the organisation (and Everton’s team, for that matter). Also, it was hard to attract many players as union members whose wages did not approach the cap level. The NAFPU folded in 1901. Some biographical articles state that John, himself, joined Tottenham Hotspur in May 1898 but surviving newspaper reports appear contradictory on the matter (John Cameron did move to Spurs in June).

What is certain is that come August, John was headed for Glasgow – but to sign for Celtic, not Rangers (the fee set at £200). The Scottish Referee publication noted that at Parkhead he was: ‘Imparting that dash, power, and go-ahead style’ which are wanting. He won a further five international caps once in Glasgow. Silverware came in the form of successive Scottish Cup victories in 1899 and 1900. In the 1900 final – an Auld Firm encounter – John soldiered on with a bandaged knee after being scythed down. As full time approached he swung his ‘good’ leg to score Celtic’s second goal and ensure that the trophy went to Parkhead.

After two seasons in Scotland in July 1900 John was reported to be returning to Liverpool to found a cycle shop business. Although he had been described in one report as an ‘extinct volcano’ in his final months with the Bhoys, the Scottish Refereespeculated that John ‘will again make Mr. Molyneux’s acquaintance.’ The Mr. Molyneux in question was Dick Molyneux, the Everton Secretary. In fact his next port of call, in November of that year, was just across the Mersey. Ambitious Football League newcomers, New Brighton Tower offered Celtic a transfer fee that Bolton Wanderers could not match. John made an instant impact on the Wirral side, but Tower had over-reached. Low attendances made the club an unsustainable concern – ceasing activities in the summer of 1901. So John sought a return to Goodison Park and, after a period of deliberation the club officials put aside distaste about the earlier union activities and re-signed the forward in July for a transfer fee of £60. Wages were set at £3 per week all year round (raised to £4 later that year). It seems that John had another string to his bow as a producer (or at least promoter) of footballs. In October 1901 the Everton board minutes recorded that a sample of his ‘Boss’ football was requested for inspection and consideration.

John scored twice on his second Toffees debut and made 24 appearances in the push for the Blues second League title. In spite of beating Sunderland home and away, it was the Wearsiders who got past the finishing post, three points clear of Everton. A similar number of appearances were made in 1902/03 but the Blues had a disappointing mid-table finish. In early June 1903, John bade farewell a second time. He was, by now, 34 and deemed to be expendable. For new employer, Preston North End, the veteran contributed 10 goals to their successful promotion push to the First Division. Injuries became increasingly regular but in the 1905/06 season he played his part in getting the Lilywhites to a second place finish in the League, behind champions Liverpool. In 1907, as he approached the 40 mark, John hung up his boots but remained at Deepdale as team coach.

That same year, a second – and more successful – attempt was made to establish a players’ union. When the Association of Football Players and Trainers Union (later re-christened the Professional Footballers’ Association some time later). The union held its inaugural meeting on 2nd December 1907 at the Imperial Hotel in Manchester. Attendees were predominantly from the two Manchester clubs but John was also present – a physical link with the first footballers’ union.

John continued to manage his bicycle store in Kirkdale (combined with coaching Preston) before uprooting himself and emigrating to Canada early in 1911. It is believed that he went there to practice his trade in shipbuilding rather than anything linked to sport. The rest of the family remained at 57 Hawthorne Road – close to Kirkdale railway station – with Isabella combining domestic chores with keeping shop (it is now a barber shop). The exiled husband returned in July 1914, determined to get a role back in English football. He was promptly appointed as a youth coach with North End but he stood down in August 1915. A 1926 newspaper report confirmed that he was still living in Kirkdale – a decade later he was residing in Waterloo.

On 12 April 1956, at the grand age of 87, he passed away at 20 Birket Square, Wallasey, from kidney and prostate complaints. Isabella had died in 1948. His occupation was listed on the death certificate as ‘retired manufacturing confectioner’ (presumably this was a business he ran after the cycle enterprise). Fittingly, the great man – dashing in looks and sporting nature – is laid to rest within sight of Goodison Park at Anfield Cemetery. Footballers gracing the two nearby stadia should, perhaps, pause a moment to give thanks for John’s pioneering work in protecting players’ rights.

Footnote: Laurie Bell

It is little surprise that Lawrence ‘Laurie’ Bell is somewhat overshadowed by his more illustrious elder brother; but he enjoyed a fine sporting career.

Born in 1872, Laurie followed John into the Dumbarton team of the early 1890s, fully establishing himself in the forward line after his brother departed for Goodison Park. He, too, headed to England after a season at Third Lanark, but was Yorkshire-bound. At Sheffield Wednesday he won the FA Cup in 1896, transferring to Everton – for a fee of £200 – a year later (the Toffees beat off competition from Aston Villa for his signature). After two seasons at Goodison (one alongside John) in which he contributed 20 goals in 48 appearances, he was transferred to Bolton Wanderers where he enjoyed his most prolific goal-scoring period. Spells at Brentford and West Bromwich Albion followed.

Having retired from professional football, he settled in Dumfries, the home-town of his wife, Margaret. Here they ran a tobacconist shop and raised their two children, William and Elizabeth. He did turn out for a number of local teams: Maxwellton Volunteers FC (1905-1908), Dumfries FC (1906-07) and 5th King’s Own Scottish Borderers FC (1908-09). The latter two teams would later merge to form Queen of the South FC. Well known in local circles for his proficiency on the bowling green and membership of the Greyfriars’ Church congregation, Laurie passed away on 7th April 1945 at his home, Sherbrooke, on Dalbeattie Road. He lies in Dumfries High Cemetery.

John Bell Honours

Scottish League Winner: 1890-91 (Dumbarton), 1891-92 (Dumbarton)

Scottish FA Cup Winner: 1898-99 (Celtic), 1899-00 (Celtic).

Lancashire Senior Cup Winner: 1896-97 (Everton)

Eleven Scotland Caps 1890-1900 (debut v. Ireland, 29 March 1890)

Acknowledgements and Sources

Jim McAllister (Dumbarton FC historian)

Ian Black

Morris Service

Tom Smith

Alison and Peter Jones

Billy Smith (Blue Correspondent)

Play Up Liverpool website (Kjell Hanssen)

Evertonresults.com (Steve Johnson)

The Everton Collection Charitable Trust

Spartacus-educational.com

thecelitcwiki.com

The Everton Encyclopedia (James Corbett)

The Sons of the Rock (Jim McAllister)

Behind the Glory: 100 Years of the PFA (John Harding)