Bobby Irvine, the Everton forward whose threepenny-bit dribbles used to have the million-pound note look.

(Ranger – Liverpool Echo, 1954)

Rob Sawyer

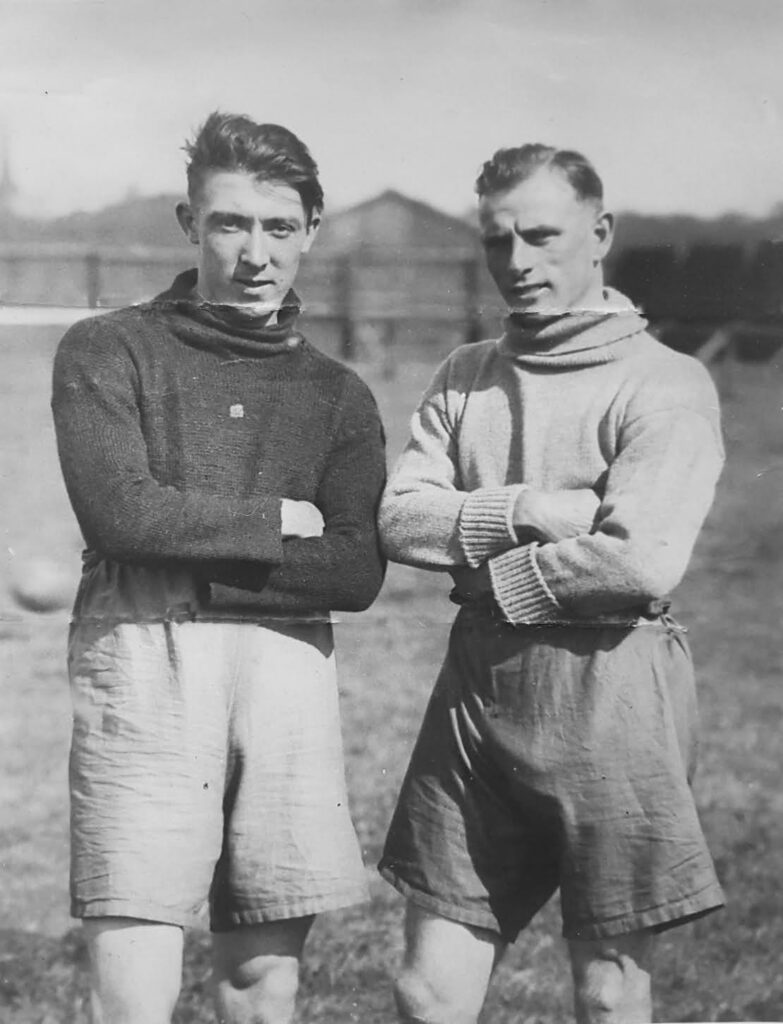

Hard as it is to imagine, forty years before George Best was thrilling football supporters up and down the land, Northern Ireland possessed a forward of similar talents – who played for Everton, rather than Manchester United.

Born on 29 April 1900, and raised on Low Road in Lisburn, Robert W. Irvine (always known as Bobby) made his name as a skilful and versatile forward, with a gift for dribbling, while playing for Dunmurry in the Intermediate League. There, he won Junior international honours for the Irish Football Association, starring in a 1-0 defeat of Scotland at Celtic Park in March 1921. In addition to being on Dunmurry’s books, for a period he was on Belfast Celtic’s Irish League roster, but as the famous club had dropped out of the game temporarily, owing to the fractious political situation, he was released by them.

Seeking to cash-in on their star, Dunmurry FC wrote to Everton (and, no doubt, other clubs) in July 1921 ‘strongly recommending’ Bobby as a prospective signing. It was agreed to have the Irishman over to Goodison for some pre-season training and trial matches. Having taken part in a Blues vs. Whites (first vs second XIs) match on 22 August he returned home. A month later club director Mr Fare was sent by the Toffees board to watch Bobby play for Dunmurry, and report back. On Fare’s firm recommendation, and perhaps aware of rival interest from Sunderland, Partick Thistle and Dundee, club secretary Tom McIntosh and director Ernest Green went over to negotiate a deal – getting the fee down from the asking price of £1000 to £500. Bobby would receive £5 per week, rising to £6 – plus a £10 signing-on bonus (it was reported that Everton made a goodwill gesture to Belfast Celtic to play them at some future date, in view of them previously releasing the player on a free transfer).

Bobby, who stood 5ft 9ins and weighed 11 stone, debuted for Everton’s reserve team on 3 October 1921, a few days after signing. The Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury reporter gave his assessment of the promising 21-year-old: ‘Everton played their latest capture from Ireland, R. Irvine, at inside right and he gave a most creditable display. He fed Spencer at outside right with some neat passes and was always ready for a shot at goal.’

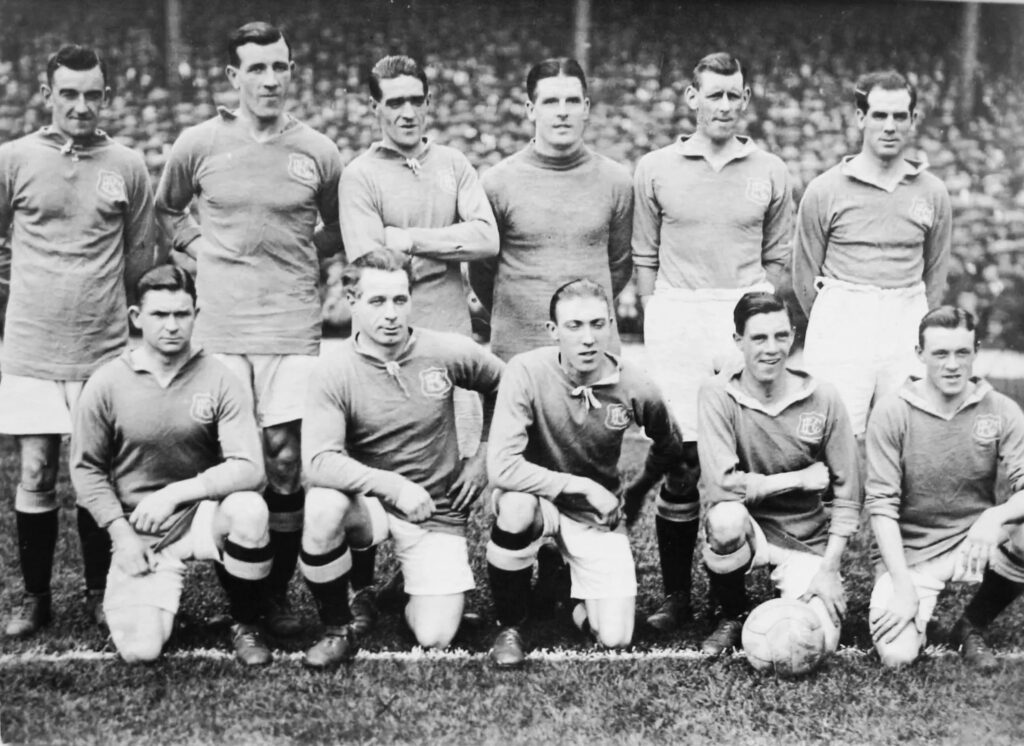

Supporters would have to wait to get a glimpse of the new man in first team action – and when they did it was in the Merseyside derby, at Anfield on 14 November. Sam Chedgzoy scored for the Toffees in the 1-1 draw. Bobby, playing at centre-forward was described as showing ‘a fine knowledge of the game’ by the Liverpool Courier, which went on to predict that he would improve with experience.

Soon established as the Blues’ first-choice centre-forward, Bobby scored two hat-tricks in his debut season in England. His quick-fire treble against Aston Villa at Goodison Park in January 1922 would go down of a highlight of his career. Villa were leading 1-0 at half-time and had just added a second when everything changed. The amazing sequence of events was described vividly in the Liverpool Courier:

‘Seventeen minutes of the second half had elapsed when Harrison took a corner, and the home leader hooked the ball into the net. Straight from the kick-off he dashed away again after Barson had partially stayed his progress he dashed over the line with the ball at his feet. It then seemed that a Villa player hit him [Frank Barson had, indeed, punched Bobby and was later sanctioned]. Other players of both sides joined in, while the referee, unconscious of what was happening, walked towards the centre. The Villa trainer and a linesman both ran towards the scene of action and when the referee returned, the ‘Donnybrook’ business coming to an end, nor were there any more signs of temper to mar an otherwise thrilling game. The spectators were naturally delighted to see Everton on level terms, but when Irvine ran straight through once more to beat Jackson for the third time, the crowd rose at him, and the cheering was deafening.’

Bravery, goalscoring ability and bewitching ball skills soon established Bobby as a Goodison Park favourite. The Liverpool Echo referred to his ‘innate artistry when in possession of the ball’ which earned him the sobriquet ‘The Prince of Dribblers’. Within six months of the move to Merseyside, he made his senior debut for Ireland, in a 2-1 defeat to Scotland. 14 more caps would follow, in which he scored several important goals – notably two in a 3-0 win over Wales in Wrexham and one that gave Ireland a 3-2 lead against England at Anfield in 1926 (the match finished 3-3).

With Wilf Chadwick filling the Blues’ centre-forward position in 1922/23 (later replaced by the flamboyant Jack Cock), Bobby switched to inside-right, which better suited his considerable skill set. There he would form an intuitive understanding with Sam Chedgzoy of the right of the Blues attack. In March 1925, his partnership began with a fresh-faced W.R. Dean, recently signed from Tranmere Rovers. ‘Dixie’, who arrived at Everton four years after Bobby, had no doubts as to the Irishman’s talent, as evidenced in a 1971 interview with Michael Charters of the Echo:

‘It is ridiculous to hear people say today that the old-time footballer wouldn’t live with the modern-day player. They talk about George Best being the greatest. Well Everton had this Irish boy, Bobby Irvine, who could dribble the ball from one end of the field to the other and nobody could take it off him.’

As the seasons passed, there was a perception on the Goodison Park terraces that Bobby, masterful dribbler that he was, sometimes overdid the individual element of his game, to the detriment of the team’s performance. Perhaps, like Peter Beardsley in the early 1990s, he just operated on a different level to some of his Toffees teammates? He was also troubled by injuries as he got older, many brought on by the cynical roughhouse tactics of opposing full-backs and wing-halves. The journalist Ernest Edwards (Bee) once wrote of him: ‘I don’t know any forward who has had more hard knocks and has not squealed about them.’

The Lisburn man started the 1927/8 season where he’d ended the previous one – as a right-winger. On the opening day he played alongside Dixie Dean in a 4-0 defeat of Sheffield Wednesday, but picked up an injury. Ted Critchley came into the side and kept his place. It seems that the Everton directorate took the decision that Bobby’s ample talents no longer fitted into the teams’ tactical plan and did little to rebuff enquiries made by clubs such as Derby County that autumn. The board met on 6 December and decided that, in light of these ‘earnest enquiries,’ the club would invite best offers for the forward – subsequently setting a guide price of £4,500.

Bobby had a run of eight games at inside-left over the festive period, in place of Dickie Forshaw, and played well – tempering some of his natural attacking flamboyance. However, by late February he was out of favour, once more. He didn’t want to leave Everton, but all-too-aware was made aware of his employer’s desire to offload him – especially when Ernest Green and Tom McIntosh headed to Glasgow for the Scotland-England international match, with a remit to negotiate a transfer if any club would offer £3,000 or more. Sheffield Wednesday were interested but could not meet the fee demanded.

In early March 1928, Portsmouth agreed to pay £3,000 over two instalments. And so, after 214 appearances and 57 goals, Bobby had little choice but to leave Everton and seek to rekindle his career on the south coast. In doing so, he dashed any chance he had of collecting a League Championship medal if Everton got over the line (being one short of the 10 appearances required to qualify). It was a decision he would go on to regret.

In bidding a sad farewell, Ernest Edwards (Bee) of the Liverpool Echo wrote:

Most people would be startled with the news of Irvine’s departure from the city. Irvine has endeared himself to the public of Liverpool by his thoroughly sporting game. I don’t know any heartier player; I don’t remember any footballer who, off the field, could talk football sense to equal Irvine, and, of course, he had a peculiar ‘Rafferty’ touch that lent a rich brogue to whatever he declared. He was known in the clubroom as ‘Rafferty’ but to the public he was always ‘Bobby’, and it is a great pity that any player so competent to work the ball, wheel about, and take chances such as he took, is leaving the city because he does not fit a particular scheme of things at Goodison Park.

Bobby’s Goodison exit prompted a flurry of letters to sports editors of Merseyside’s newspapers. Correspondents felt the club was undermining its chances of securing the League title (in the end, Dean’s 60 goals did the trick, and the Toffees purchased a great new inside-forward in Jimmy Dunn). This letter sent by ‘Castleraven’ to the Echo gives a flavour of:

Might I take the liberty of expressing condemnatory remarks concerning the transfer of Irvine? Can Everton afford to dispense with the services of a player of international repute, whose high standard of football efficiency is only equalled by his keen sense of sportsmanship? Can a substitute of sufficient dexterity be found to act as deputy to this prince of dribbles? Can Everton provide an equivalent of sufficient adroitness to emulate Irvine as a ball manipulator? I leave the question to Evertonians, whose intellectual propensities enjoy the capability of appreciating real football.

For Portsmouth, the high-profile signing was seen as key to a (successful) bid to stave off relegation. Ironically their very next match was at Goodison Park, but a gentleman’s agreement meant that Bobby didn’t play in the goalless stalemate: ‘We wanted to let Everton down lightly under the circumstances’, a Pompey director humorously commented. He did get a chance to play at Goodison in October 1928, when selected for Ireland against England. Ernest Blenkinsop, the Sheffield Wednesday full-back, making his England debut in that match, recalled: ‘This Irish Irvine was one of the finest dribblers of the ball I have ever seen or played against.’

Bobby’s time on the South Coast was punctuated by injuries which restricted him to 39 appearances and forced him to miss the 1929 FA Cup Final. Out of favour in the summer of 1930, with Pompey hoping to recoup £2,000 from his sale, he was set to join Derry City on loan. Sport, the Dublin-based newspaper, wrote: ‘The capture of Bobby Irvine…created tremendous interest in the Maiden City. It marks a forward move on the part of the Derry club. Mr Joe McCleery and his directors are to be congratulated.’

However, the celebrations were premature as, at the 11th hour, Portsmouth consented to Bobby being loaned to Connah’s Quay and Shotton FC, not far from his old Merseyside stomping ground. This spell on Deeside was curtailed by the club’s parlous financial situation, but he became their only player to be capped by Ireland. He still had magic in his feet, as made clear in this Flintshire County Herald match summary of a fixture against Mossley: ‘Bobby Irvine was positively brilliant, showing dazzling footwork and a generalship in attack which became infectious.’

Two months after joining Connah’s Quay, Bobby made the short move to Chester, turning out for the Cheshire County League outfit for the rest of the season. He left just prior to their elevation to the Football League – perhaps as Chester found the transfer fee still being sought by Portsmouth prohibitive. So, for the next two seasons he did, finally, represent Derry City – and did so in fine style. He was rewarded with his 15th and final cap in December 1931. He also represented the Irish League twice in 1932 and it is little wonder that he continued to be linked with Football League clubs. Blackpool FC was a suitor but, again, the fee sought by Portsmouth was a stumbling block. He clearly made an impression in his two seasons on the north coast or Ireland. One Derry supporter-cum-bard called Ed Lynch even penned some poetry in his honour.

Only when Pompey granted the forward a free transfer in the spring of 1933 did Bobby make a return to the Football League. Watford’s manager, Neil McBain (a former Everton teammate) signed the 33-year-old up for the Division Three (South) club. He made 22 League appearances but didn’t re-sign for the Hornets in the spring of 1934.

Come the autumn, he returned to Ireland – this time playing for Irish Free State club, Waterford. A heart-warming story concerned a match in which a Reds United player, John Lappin, broke a leg in a collision with a Waterford defender. Lappin took up the story in the local press: ‘Bobby Irvine was on the opposing team, and just after I got the injury, he would not allow me to rise from the ground. His action saved me from being put permanently out of the game, for the doctor at Mercer’s Hospital told me that if I had not been kept down, I would have received a compound fracture.’ By the following season Bobby was player-manager of the team but was sacked in January 1936 after a 7-0 defeat by Bohemians in the Free State Cup. Almost immediately, he was taken on by Brideville for the remainder of the season – his final club in a distinguished career.

On 6 November of the same year, he was announced as the new trainer-coach of Ards FC, but just a fortnight later he accepted a post as a telephone engineer foreman with the General Post Office (GPO) in Leicester. Bobby’s brother-in-law held a senior position with the organisation and had ‘put a word in’. So, Bobby and his wife Emily, who hailed from the East Midlands, set up home in a new city and remained there for the rest of their lives.

The football boots were dusted off and the former Ireland star turned out for the GPO works team. When the travelling circus came to town each year, it contacted Bobby and his GPO gang to put the temporary telephone connections in. In return they’d be given complimentary tickets for them to attend a performance. In 1965 he retired and was awarded the Imperial Service Medal, in recognition of ‘meritorious service’ to the GPO. Emily, meanwhile, had worked in the restaurant at the local Lewis’s department store.

Bobby’s grandson, also called Bobby, has treasured memories and stories passed down of his grandfather. Booby Sr. served in the Home Guard during the Second World War. Following some localised German bombing, he was checking the roof space of his flat for incendiary bombs, when he fell through the ceiling – he emerged unscathed. There is another tale of Bobby inviting Italian POWs stationed in the East Midlands into his home on Christmas morning to offer them cups of tea, as it was snowing outside. In this era, he would often go drinking in the Old Horse pub, opposite Victoria Park. If the US servicemen frequenting the pub missed their last truck back to the base at Stoughton, he’d let them crash at his house on Queens Road. His wife and daughter (Jeane) were hoping to meet a Clark Gable look-a-like, but they were frequently disappointed! In her early teens, Jeane would know the Attenborough brothers (Richard and David) and play in Victoria Park with them. Later, she briefly stepped out with Don Revie, when he was Leicester’s star striker in the late 1940s.

Bobby never lost his passion for Everton and would make a beeline to Filbert Street whenever the Toffees were playing there in the 1930s and 1940s. His grandson, who describes Bobby as a lovely man, remains a devoted Toffee and was up at Goodison Park for a match several season ago.

Bobby lived with dementia in his final years but got to meet his first great-grandson, Ryan. Bobby Irvine, Lisburn’s very own wizard of the dribble, who went on to grace Goodison Park for seven years, passed away in on 6 December 1979.

Acknowledgments

Brendan Connolly – who wrote a match-day programme article about Bobby in 2021

Bobby and Jeane Brown

Billy Smith (bluecorrespondent.co.uk)

Liverpool Echo and other regional newspapers

Steve Johnson, evertonresults.com

nifootball.blogspot.com

Ken Rogers ed., Dixie Dean: The Lost Interview

James Corbett, The Everton Encyclopedia

Image colourisation by George Chilvers