by Rob Sawyer

‘When I hitched my chariot to the Goodison Park star, I did myself the best service ever. No club could treat its players better.’

Eddie Wainwright, Liverpool Echo 1955

The immediate post-war era for Everton was one of austerity, much in keeping with that felt by a battered Britain. The Toffees’ squad had been ravaged by age and star-player exits since the club was crowned Football League Champions, a few short months before Nazi forces marched into Poland, precipitating a global war.

Tommy Eglington, Peter Farrell and Wally Fielding proved to be astute signings, but the team was on a downward trajectory. This made it hard for local youngsters coming through the ranks to develop to near their full potential. Eddie Wainwright was, perhaps, the sole exception. Although seemingly frail, the noted sport journalist Stork described the nimble inside-forward as having the heart of a lion. He had scored at a rate of better than a goal every three matches to get to the brink of full international recognition. His career then came to an abrupt and prolonged halt through a terrible leg injury sustained in late 1950.

Eddie was a Southport lad, born on 22 June 1924 to his namesake father, Edward Francis, and Agnes. He was raised at 192 Wellington Road in the seaside resort. Always slight of build, he played for his school, team and went on to represent Southport Schoolboys. He also represented the local side Hesketh Fleetwood in the Southport and District League. He signed amateur forms with Everton in 1939 but within months, war broke out and his registration was effectively annulled. Away from football he served his apprenticeship as a motor mechanic.

Too young to enlist with the armed forces at the outbreak of war, he subsequently joined the British Army as a Physical Training Instructor. Based in Teesside, he made 12 appearances for Middlesbrough in the 1944/45 and 1945/46 seasons. He would also make a number of outings for Army representative teams in matches staged to boost morale, notably against Scotland at White Hart Lane in December 1945, in which he lined up with Joe Mercer. Another teammate in the Army forward line was Wally Fielding – with whom Eddie would be reunited at Everton. Eddie would credit the training skills of Spurs’ Arthur Rowe, who oversaw the Army team, for aiding his development.

In August 1943, with encouragement from his father, Eddie had written to Everton’s secretary, Theo Kelly, asking about the possibility of being re-engaged by the club. He was duly re-signed as an amateur. He made an instant impression. A report of the Blues 8-0 defeat of Napier, on 8th September in the Liverpool Combination, noted:

Makin and Wainwright scintillated in the Everton attack, Makin getting three goals and Wainwright one. Both these boys should do well. Wainwright, who comes from Southport, is finely built and forceful. Makin lacks nothing in confidence and is deadly in front of the goal.

In contrast to Eddie, George Makin would not make the breakthrough at Everton in peacetime football, but he would later star for Pwllheli FC under the stewardship of T.G. Jones. Just three days after the rout of Napier, Theo Kelly broke the news to Eddie that he’d be lining up for the first team, away to Manchester United. Professional forms were hurriedly signed, and the 19-year-old took to the pitch alongside T.G. Jones, Joe Mercer and Tommy Lawton. The debutant was praised for his clever movement, but the Blues fell to a 4-1 defeat. Eddie would soon become a regular in the Everton first XI – clocking up 66 appearances (36 goals) in wartime league and cup football. Of Lawton, Eddie would state: ‘He was the best centre-forward I have seen. His shots with either foot were like bullets and he seemed to get the same power with his head.’

When the Football League programme resumed in August 1946, Eddie was selected at inside-right in the forward five for the visit of Brentford. After a period out of the team, in the wake of the 2-0 defeat, he established himself in the number eight shirt with Wally Fielding at inside-left. The burly Jock Dodds led the attack, of whom Eddie later would comment ‘He was past his best, but I was amazed at the agility in such a big man, because he must have weighed over 14 stones’. Dodds would return the compliment by hailing Eddie as one of the finest inside-forwards in the immediate post-war era. Eddie ended the 1946/47 season with a very creditable 16 goals in 29 league and cup appearances (just one behind Dodds’ tally), but Everton had an underwhelming mid-table finish.

The sandgrounder continued to deliver an impressive goal return in the following seasons. After missing a chunk of the 1948/49 season with appendicitis, he returned to enjoy a career highlight on a snowbound pitch in March 1949. He would praise the work of the Goodison ground staff who worked tirelessly to get the game on against the odds. Alan Storey, who was on the staff, later recalled: ‘No sooner had you finished one stretch of touchline than you hard to start again, so hard was the snow falling.’ The Tangerines, defending the Gwladys Street end with snowflakes coming over the Bullens Road stand roof and into their faces, were four down by half-time with Eddie completing a hat-trick within the first 32 minutes. He rounded off the scoring with his fourth, and Everton’s fifth, in the second half. Dubbed The Wizard of the Blizzard by the papers the next day, he later reflected for an Everton programme article: ‘Frankly, the game should never have been completed. At times the ball was covered in snow and the Blackpool players kept asking the referee to call a halt. If we hadn’t quickly run up a three-goal lead I think he would. But as Everton needed the points it was important for us, and he let us carry on.’

Eddie, although quiet, was well-liked and struck up friendships with several teammates, including Peter Farrell and Tommy Eglington. The forward had little appetite for food in the build-up to matches, so the Irish duo would set either side of him at lunch and whisper in his ear, ‘Eddie, order the steak’. They’d then polish it off for him. Eddie would also play golf every Monday with his steak-devouring pals plus Don Donovan. Eglington would reminisce after Eddie’s passing: ‘Eddie was always a great teammate. He was a very helpful man in every way possible and, of course, he was also a very good footballer.’

On 12 December 1949 Eddie tied the knot with Mabel Pritchard – the sister of one of his childhood best friends. They would go on to have two sons (Michael and Steve) and a daughter (Susan). Six years later, an Echo article featured the couple in their marital home at Blenheim Avenue, Litherland (where they had moved to from Southport in 1952). As well as tales of how they met and how Mabel and Michael were his fiercest footballing critics, Eddie revealed his off-pitch passion for horticulture. He was an active member of the Southport Chrysanthemum Society and had successfully exhibited at the town’s famous annual flower show. The article also highlighted that, unusually for the era, Eddie had a flair and passion for cooking. He would prepare breakfast for the family every morning and, when his football commitments permitted, laid on lunch, too.

The forward’s finest campaign was undoubtedly 1949/50. With 13 goals, Eddie was the leading goalscorer and one of only two players to reach double-figures in a goal-starved team (Harry Catterick being the other). A contemporary pen picture of the forward by Stork described him thus: ‘He is the quicksilver type, with excellent ball control, a strong shot in either foot and a sharp football brain, which enables him to size things up a move ahead of the other fellow.’

In the fifth round of the FA Cup, he held his nerve to convert from the spot to defeat the famous ‘push-and-run’ Spurs side. He also netted in the sixth-round victory over Derby County – setting up an all-Merseyside derby at Maine Road in the semi-final. Terrace chants were more inventive back then and Eddie had a ditty penned in his honour (tune unknown):

All the fans fall for Eddie Wainwright

And their thousands shout encore

For there’s magic in Eddie Wainwright that makes you want to roar

He’s fast and clever, he bangs that leather

He’s the Toffees’ pride and joy

He fights with might and main

We might be on that Wembley train

Hip hooray, Eddie Boy!

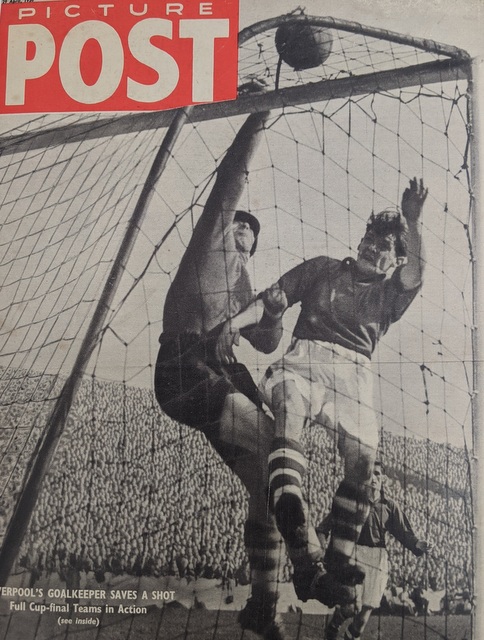

Having spent three days relaxing at a Buxton spa hotel, the team stopped for a lunch of eggs on toast en route to south Manchester. They arrived at the stadium to be met with a throng of supporters proudly displaying their red and blue colours. During the match Eddie was shackled by the tenacious Bob Paisley. He’d rue the role he had in the Reds’ second goal, ten minutes from full-time. Close to his corner flag and under pressure from Jimmy Payne, he committed the cardinal sin of clearing across his own area. The pass, intended for Tommy Eglington, was intercepted by Billy Liddell. Moments later the part-time pastor had blasted the ball into the net. ‘I felt awful,’ said Eddie. ‘If there had been a hole in the pitch I would have probably gone down it…After that [match] I went home straight away. My wife was waiting in the car, so I didn’t go home with the lads. I went home to Southport and, as far as I recall, I didn’t go out that night.’ As they drove home the couple would see supporters – some cheering, some dejected – on the long drive back along the East Lancs Road.

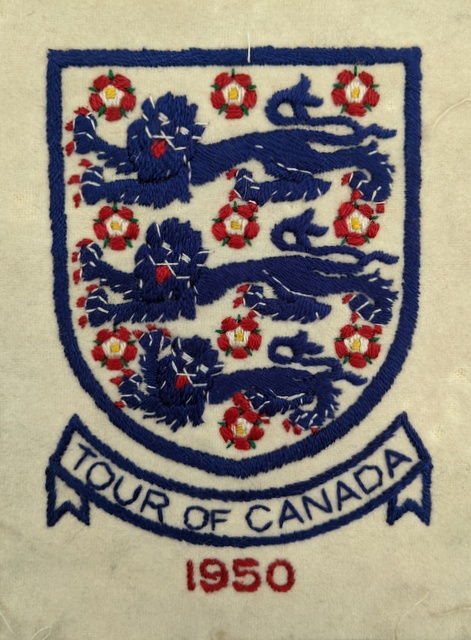

Some compensation for the cup defeat was selection for a Football League select side to play an Irish League XI in Belfast in April. To cap it all, he was invited to be a member of the Football Association’s ‘goodwill’ touring party to North America at the season’s end. Included in the party were the likes of Stanley Matthews (who would cut short his participation in order to link up with the first team squad in Brazil for the World Cup) and Nat Lofthouse. Having sailed the Atlantic, the party were launched head-long into an intensive programme of matches and travelling between territories, much of it by rail.

Against a series of regional Canadian teams Eddie scored eight goals in six appearances – including two hat-tricks. Matches were also played against touring sides of Manchester United and Jorkopping (Sweden). The tour rounded off with a 1-0 defeat of a USA All-Stars side in New York (containing ten players who’d subsequently take on and defeat England in Brazil). Eddie came back to Merseyside with a two-gallon Stetson hat, given to him on Calgary, and priceless memories of seeing the Rockies from a train, visiting the Niagara Falls and counting 180 icebergs on the voyage home on the Empress of Canada. Eddie was optimistic of being invited on the FA tour to Australia planned for the following summer.

Football fortunes can fluctuate wildly and without warning. For Everton the warning signs of the previous season would be borne out by relegation in the spring of 1951. By this point, Eddie was a helpless bystander – indeed he was struggling to stand at all. His season had started with a personal goal drought but, after a period out of the team due to a nasty knee injury, he got off the mark in a home defeat to Derby at Goodison Park on 9 December. With the Blues trailing 2-1 in misty conditions, Eddie bore down on goal, seeking a late equalizer. Don Kendall (Pilot) reported on what happened:

‘Wainwright, just inside the penalty area, called for and received the square pass from [Oscar] Hold and, as he explained afterwards, he thought he was clear. Eddie tried a diagonal shot and put all his strength behind it. At the same time Chick Musson came over to cover and Wainwright kicked Musson instead of the ball and both the tibia and fibula were broken.’

Eddie, who was stretchered off, would absolve the Derby player from any shred of blame. As soon as Eddie headed to hospital in an ambulance, manager Cliff Britton drove to Southport to break the bad news to Mabel. He then took her to see her husband in the Liverpool Royal Infirmary. After surgery he was taken to a Lourdes Nursing Home to recuperate, Cliff Britton and skipper Peter Farrell went to see him there the following day. Eddie was allowed to go home after two weeks, with his leg in plaster.

He would benefit from the new treatment room in the Goodison Road stand, which included such mod cons as a new electrical ‘heat bath’. Nonetheless the recovery was slow as the broken bones refused to knit properly. In June 1951, inaccurate speculation was rife that the forward was on the verge of hanging up his boots. At this point he was still on crutches and having daily physiotherapy sessions at Southport Emergency Hospital. Finally, in July, he ditched the crutches for a walking stick and by November was able to get back out on the golf course. The football pitch was another matter, however, and it would be the tail end of the 1951/52 season before he got some game time with the Everton Colts.

He was left with a pronounced limp – possibly a result of one leg having been shortened by the injury – but he was not to be deterred. The supporters raised a hearty cheer when Eddie was seen at Goodison in the pre-season Blues v. Whites trial match in August 1952, but it would be December before he was deemed ready to return to the Football League fray. He came in at right-wing for the injured Tony McNamara on 13 December and the day could not have gone better for club or player. Eddie scored in a 5-0 rout of Bury and Stork in the Echo was full of praise for the returning hero: ‘The introduction of Wainwright at outside-right proved to be a good move. Not only did Wainwright score a goal, but he played extremely well and showed no signs of fear – not even in the most hearty tackle, and he had to face up to any number of these. Eddie could easily make the outside right position his own, for he adopted himself to the position as though he had been playing there all his life.’

Eddie had a further six outings on the right wing before returning to reserve team duties. His goal touch had not deserted him but the injury had shorn him of some of his trademark electrifying pace. Returning to the side for the second half of the 1952/53 season, he made a significant contribution (scoring eight goals) as Everton finally secured promotion back to the First Division. The season culminated in the joyous scenes at Boundary Park as Everton’s 4-0 victory saw them secure a crucial second-place finish.

Around this time a young Derek Temple had joined the club. He told me: ‘I went on the ground staff in 1954 and saw Eddie in training. He never was the same after the broken leg and had a very bad limp – but he was still a key player. I’d see him at lunchtime as I went over to the Main Stand; he seemed to be a serious sort of man compared to the other lads, who seemed more relaxed. Maybe that was because of coming back from the bad leg break.’

During Eddie’s two-year injury-enforced absence, Dave Hickson had established himself as the team’s centre-forward. The swashbuckling number nine had warm words when recalling their time together at the club: ‘He was a smashing player – he was very direct, an out-and-out winger. He would work the flanks, up and down the pitch, and send over some lovely crosses for the forwards…there was no shortage of supply from wide positions! He was also a lovely man and got on well with everybody. The camaraderie was great in our team at that time.’

Back in the top flight, Eddie continued to be called upon by Cliff Britton on the right side of attack – as an inside-forward or, more frequently, a winger. However, the resignation of Britton in March 1956 helped to hasten Eddie’s departure from Goodison. His final selection for the first team was for a heavy home defeat to Sheffield United on 30 March. He would travel on the post-season club tour of Canada and the USA – his second experience across the pond – but on his return he was offered for transfer. He ended his Everton career with statistics of 78 goals in 228 appearances – all the more impressive when considering that he played in an often-struggling team and spent the latter part of his career on the wing. Along with Gwyn Lewis and Jackie Grant, he answered the call of Harry Catterick, who was then managing Rochdale of the Third Division North (the familiarity and friendship with Catterick meant that he resisted overtures from Tranmere Rovers). The combined fee was £2,500. Eddie spent three years at Spotland, making century of appearances and later stating: ‘It was a good way to bring my career to a close.’ However, he also confessed, ‘I got kicked to death at that level.’

Upon retirement from playing, Eddie followed in the footsteps of Ted Sagar and Norman Greenhalgh to become a publican for Threlfalls. After receiving training at the Old Roan pub in Aintree, his first posting was to the Medlock – close to Goodison Park and popular with match-goers. At the first sign of any trouble in the pub, the locals would say, “Eddie, stay where you are – we’ll sort this out” and they’d throw the guilty parties out. After the Medlock came the Ship Hotel in New Brighton, followed by the Saughall Hotel (Moreton) and then, finally, the Acorn in Bebington. Eddie’s son Steve recalls John Willie Parker sometimes assisting at the Saughall Hotel as a relief barman: ‘I was nine or ten at the time. The pub shut at 3pm so me and John Willie would kick the ball in the car park for a couple of hours – then he’d open the pub up again.’

The pub work restricted opportunities to take in football games – Eddie was loathe to leave the pub, fearing things could go wrong in his absence. Steve recalls his father taking him to two midweek night matches – including a cup tie against Spurs. A man of few words, but capable of delivering a pithy interjection, Eddie did not talk a lot about his football career to his children. Steve had to tease information out of him – or get it from his mother.

In 1984 Eddie suffered an aneurism close to the aorta. Surgery was performed at Broadgreen Hospital and the procedure ‘bought’ him another 20 years. However, this was the catalyst to take retirement from the pub trade – he was about ready to step down anyhow. The couple moved to a bungalow in Bebington and lived out their days together there. Although not a regular attendee of matches he went to Prenton Park on occasion and he did stay in touch with some of his former Everton teammates.

Eddie’s grandson Danny Harrison was on the books of Everton until being released at 12. Danny told me: ‘I remember when I was in school, I did a lot of projects on my granddad. I remember having conversations with him about football – he loved his playing career. One story he told me was that for London games they’d get the train down and it was very strict. The club would take them to the theatre but then they’d then lock them into their rooms for the night – but some still managed to get out.’

Danny’s incessant practicing with a ball sometimes caused concern for the horticulturalist in Eddie: ‘He had some of his prizewinning crysanths in pots in my mum’s garden. He’d watch me and my brother there running around playing football – but as soon as we started knocking the flowerpots over it was the end of the world! For a spell I trained at Bellefield and Eddie managed to come over a couple of times with me – it was nice for him to watch me play for Everton. We thought that it might carry on, but it wasn’t to be. He managed to watch me play professionally at Tranmere before he passed. That was massive for him and the family – seeing me follow in his footsteps. As he came out of Prenton Park he got stopped by an elderly gentleman and was asked for his autograph. There was me thinking I’d cracked it and there’s my granddad getting stopped as well! It was a surreal moment.’

Eddie passed away on 30 September 2005. He went quietly – typical of the man – and didn’t suffer. At the funeral at Landican Cemetery, Z-Cars was played, and Everton FC was well represented.

Sources/Acknowledgements:

The Wainwright family

Derek Temple

Billy Smith, Blue Correspondent website

Liverpool Echo

Steve Johnson, Everton: The Official Complete Record

Everton match day programmes