By Rob Sawyer

The Toffee Lady is an enduring and iconic image, intrinsically linked to Everton FC. Since the 1950s, a Toffee Lady, or latterly a Toffee Girl, has paraded around Goodison before matches, dispensing the eponymous humbugs. But for many, the definitive Toffee Lady image takes cartoon form. It’s the Mother Noblett, famous for gracing the front page of the Football Echo for decades, looking elated, deflated or indifferent, depending on the Blues’ fortunes that day. Her ‘rival’ character was the Kopite, who showed a similar range of emotions, depending on the Liverpool result.

The creator of these enchanting characters was George Green, who entertained Merseyside newspaper and football programme readers for three decades. Born on 23 February 1892, George hailed from Holloway in London, and it was said in family circles that he drew before he could walk. His talent for doodling was unsurprising as two of his uncles were accomplished artists. The Greens moved north when the eight-year-old budding illustrator’s father set up an antiques and furniture dealership in Wallasey. George received his education at Egremont Commercial School. Six years later the family moved to Kent, and it was at Margate School of Art that George first received formal tuition in drawing. He moved to the USA, in his late teens, to chase his dream of becoming a professional artist, but homesickness brought him back to these shores.

After his war service, he ended up back on Merseyside, working as an artist/designer at a Dingle printing form. There he met his future wife, Catherine Josephine Waters, and they married in 1922. His talent for creating humourous caricatures became apparent when tasked by a Wallasey newspaper with depicting various theatre companies. These skills were further honed when joining the Liverpool Echo staff in 1925; here he became known for his brilliant cartoons and caricatures covering sport, the theatre and ‘society’ events.

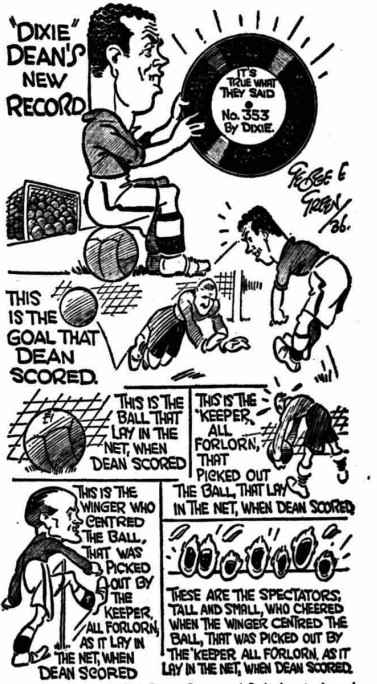

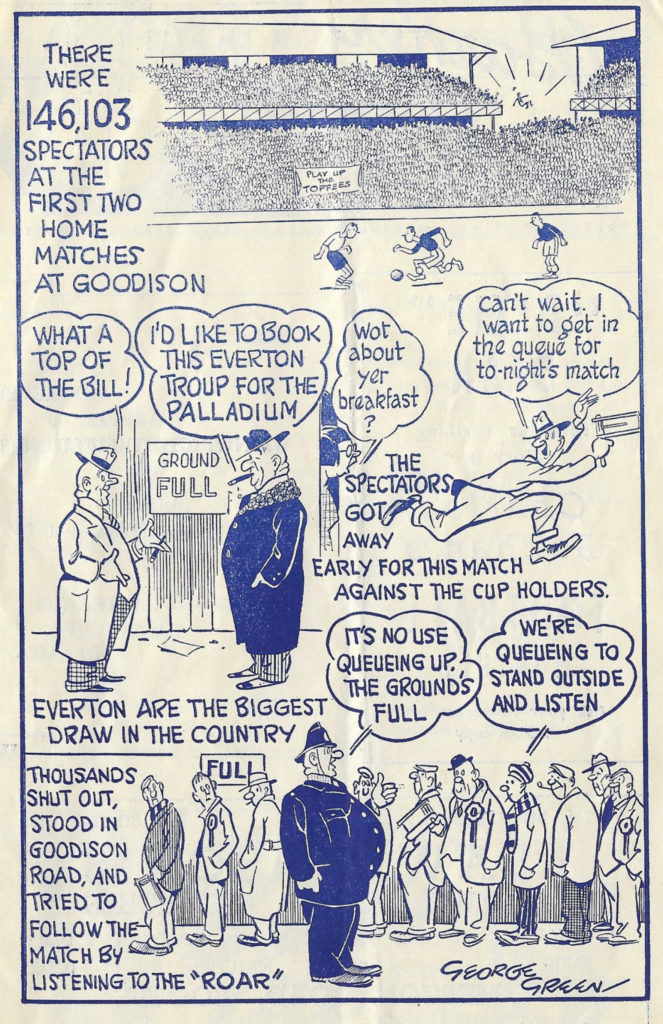

His first output was a cartoon illustrating events unfolding in a cup tie between the Everton and Sunderland. In an era when photography of matches was rare, his cartoon strips gave newspaper readers a light-hearted insight into the events on the pitch. His ‘victims’ never complained as his approach affectionate, not cutting. ‘National newspaper cartoonists did have the same artistic flair as my father,’ George’s son, Clifford, told the Echo, ‘but often they were cruel. My father worked for humour, not cruelty.’

Clifford went describe his father’s ‘less is more’ approach to crafting the superb yet simple caricatures: ‘My father spent most of his life contriving to leave lines out. The more he could leave out the better. He would never draw a full face. Just an eye or a nose. Simplicity was the key to his success.’

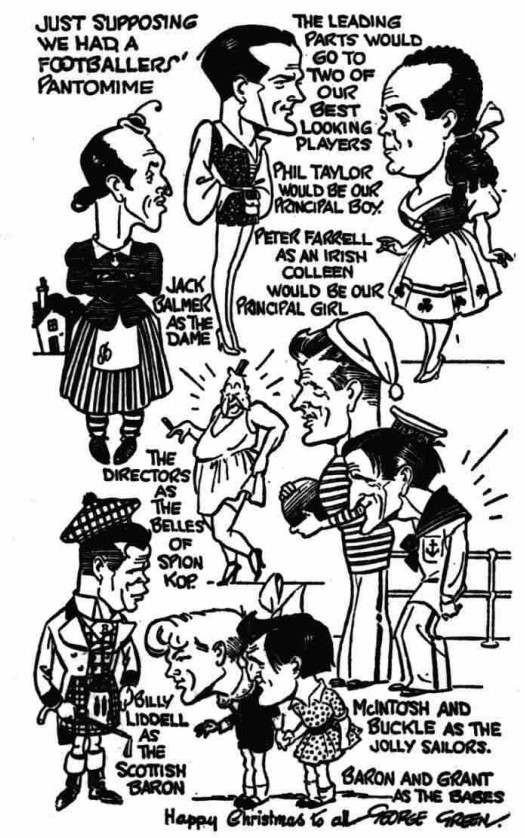

As for his drawing technique at Goodison Park and Anfield: he’d watch a particular player through binoculars and create four or five rough sketches; these would form the basis of the finished article, created later. If he was struggling to capture the players’ forms, he’d draw them naked, only adding clothing once he’d perfected the depiction of their bodies in motion. He’d capture several key moments from the 90 minutes, to give Echo readers a flavour of the match. There were rich pickings from the Everton ranks, with Dixie Dean, Tosh Johnson and Alex Stevenson being among his regular picks. One of his favourite sketches was of the great Dean firing balls from a tank at a hapless goalkeeper.

During Everton’s triumphant 1938/39 season, George contributed cartoons for the Everton programme, a role he resumed in the 1950s. These often featured the Toffee Dame – as he referred to her – frequently ‘having words’ with opposition players or mascots. The form of the Mother Noblett he drew evolved until it became the one we are familiar with.

George had found himself torn between pursuing his love of drawing with a desire to be on the stage. He would combine the two by devising a stage act in which, according to reports: ‘He would draw on his easel the name of some well-known personality and then convert it into the face of its owner.’ He appeared in virtually every theatre in the Liverpool area, his last performance coming at the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead, in 1939.

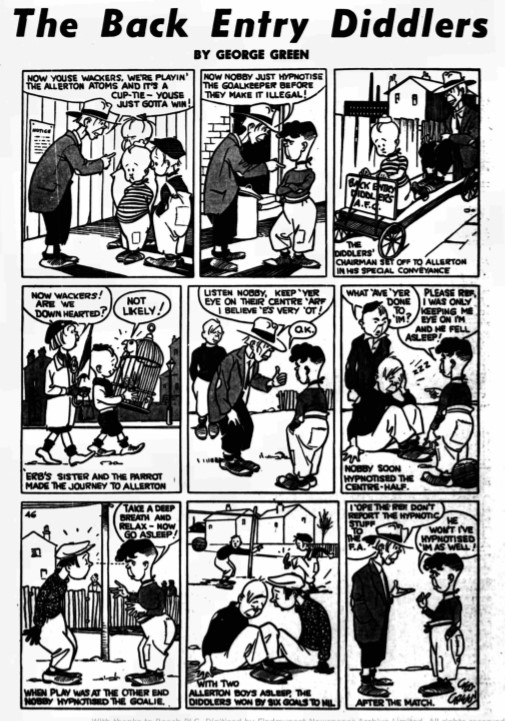

It wasn’t just Liverpool and Everton stars who were immortalised in ink. Living on the Wirral in his teens, George watched lads living off Vauxhall Road playing football in the ‘ginnel’ to the rear of the terraced houses. They made do with a burst rubber ball stuffed with newspaper – later upgraded when they clubbed together to purchase a tanner ball. Their star player was ‘Erb who, according to George, ‘could diddle round anybody’ but often got tripped by opponents. He expanded: ‘Ginger was the boss, a solemn boy who never smiled but organised everything. He even kept a record in an old exercise book of the Diddlers’ matches. I often went along to watch them and, being able to draw, made many sketches of my Back Entry friends, for each one had a personality of his own.’ In the 1930s, these fond recollections gave birth to the Back Entry Diddlers – a long-running cartoon strip in the Echo and Junior Echo, in which the Wirral lads – with their ill-fitting trousers, held up by braces – would come up against rivals in the shape of the Walton Wackers, Netherton Nippers and others. The cast expanded over the years to include the fedora-wearing manager Flynn, ‘Erb’s sister, Maggie Ann, Windy (who panicked if the ball came his way), Nudger, Jerry, Basher, Tosh and Nobby. The latter was blessed with a skill for hypnotising opposition goalkeeper but was prone to putting his teammates to sleep in the process. There was a team mascot in Cockie – a parrot with an aversion to rain. The Saturday strip was a huge hit and spawned a stage show in the 1950s, with local children cast as the key characters.

George and his wife, Catherine, lived at 21 Queens Drive. Their daughter, Gabrielle inherited her father’s artistic talents and by the age of 14 was on the stage and described as a ‘variety artiste’. She went of the replicate George’s stage act (sometimes on the bill at the Diddlers shows). In time she made the opposite journey to her mentor, settling in London, and working in showbusiness until passing away in 1971. Son Clifford would tell the Echo that his father’s first love was painting rather than sketching, but he had a love of art generally: ‘He loved art of every description. His cartoon work paid the bills.’

Chronic rheumatoid arthritis had curtailed George’s pastimes of golf, fishing and cycling by the 1940s, but he ignored the pain in his hands to continue to create visual delights for Merseyside sports fans. His final Everton contributions were the cartoon for the December 1956 visit of Sheffield Wednesday, and the post-match strip in the Echo. Taken ill soon afterwards, he was admitted to Broadgreen Hospital, passing away there on 27 February 1957. Clifford lamented: ‘It’s a pity he didn’t live to experience the Beatles and the Mersey Beat scene. He would have captured the atmosphere of that era so well. I don’t think my father knew how good he was.’

Even though the Football Echo no longer runs off the presses, George Green’s Toffee Dame endures – most recently featuring on a poster unfurled at the Gwladys Street end before the match against Wolves.

I’d be delighted to hear from relatives of George Green – I can be reached via the Toffeeweb editors: Contact / Article Submissions | ToffeeWeb

Acknowledgements

Billy Smith

Andy Weir – visit his Flickr account for scans of programmes: https://www.flickr.com/photos/bob_latchford/albums

Jimmy Harris

bluecorrespondent.co.uk

Liverpool Echo

Everton match-day programmes

More examples of George’s work