Rob Sawyer

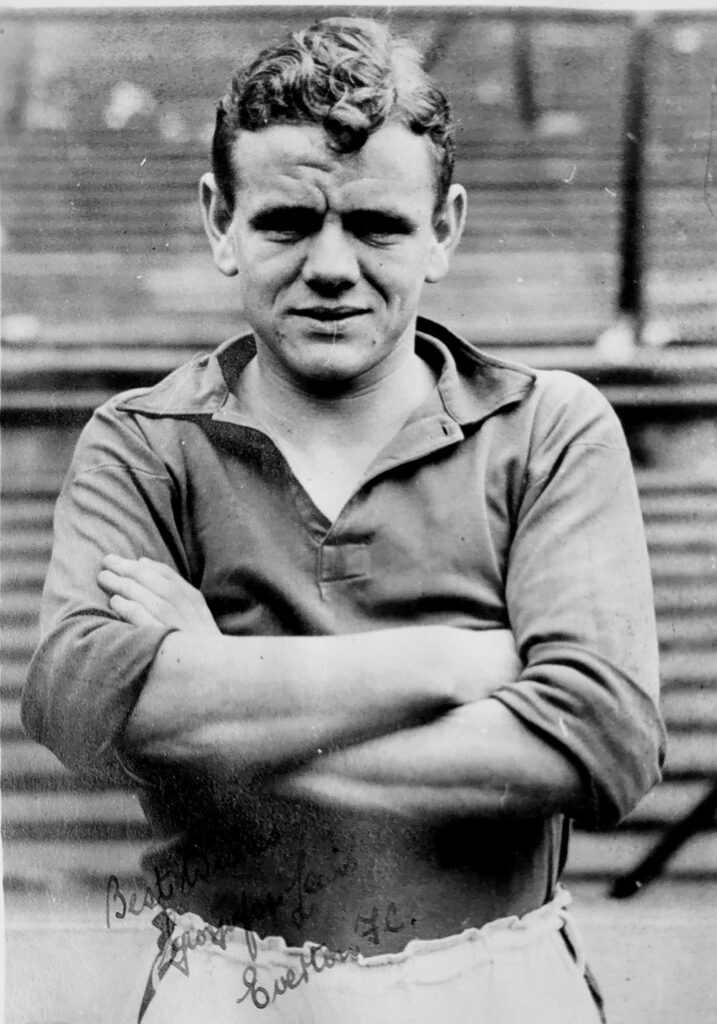

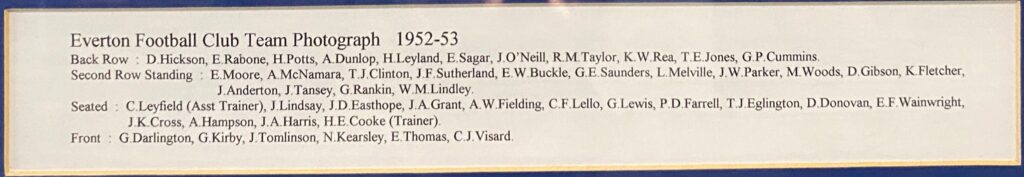

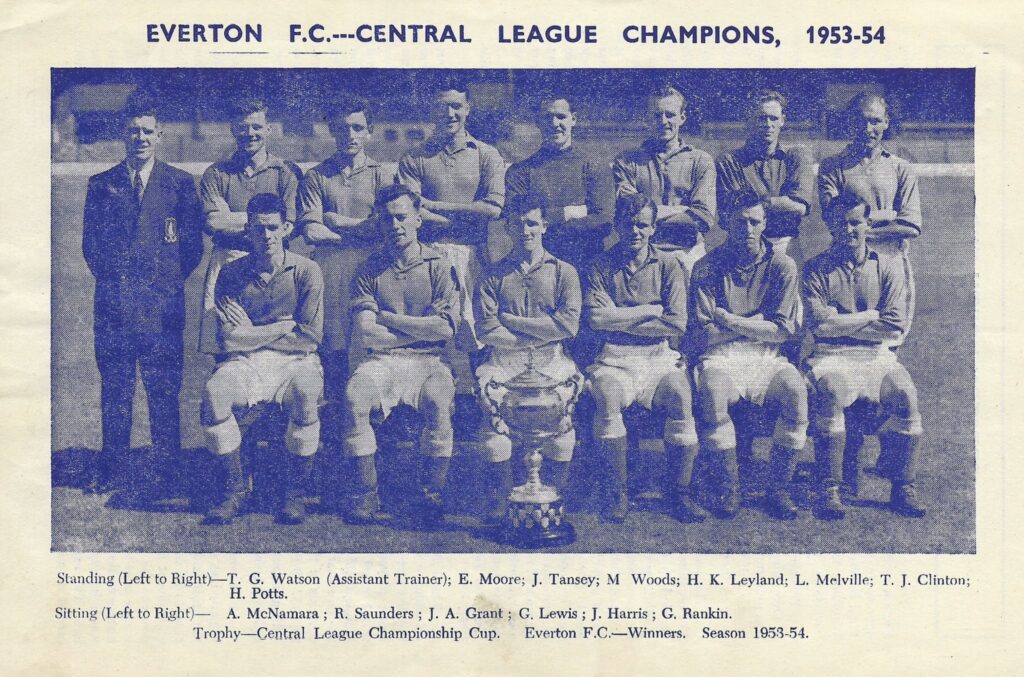

Born on 21 April 1932, Gwynfor (Gwyn) Lewis became one of Bangor’s finest footballing sons. Like fellow Bangor-born forward Nathan Broadhead, over six decades later, Gwyn would only get fleeting opportunities at Everton, but established himself as an accomplished goalscorer in lower league football.

Gwyn was one of several young talented sportspeople attending Bangor’s Friars Grammar School in the 1940s. There at the same time was John Cowell, who would go on to play in goal for Pwllheli FC under TG Jones, Bangor City, Marine and Liverpool FC Reserves, as well as cricket to a high level. An academic and sporting all-rounder, his school reports confirm his ability in class, whilst out of it he was successfully competing in football, cricket and athletics (sprinting, jumping and javelin).

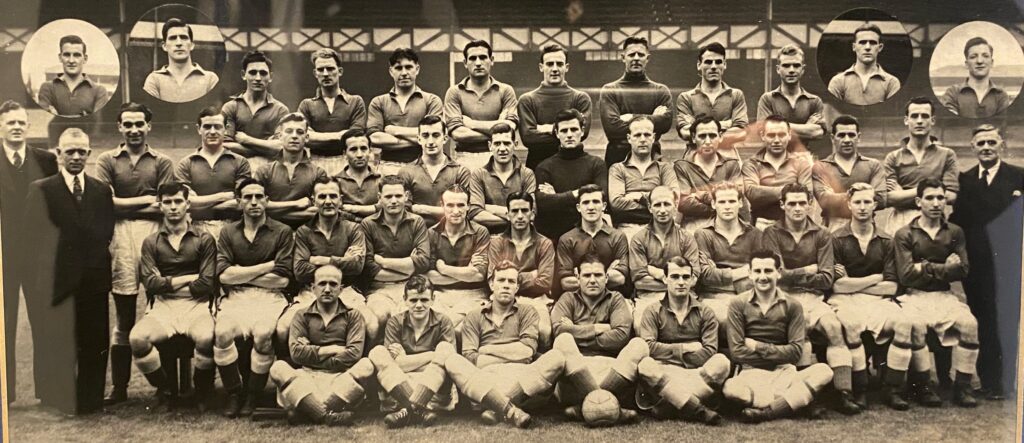

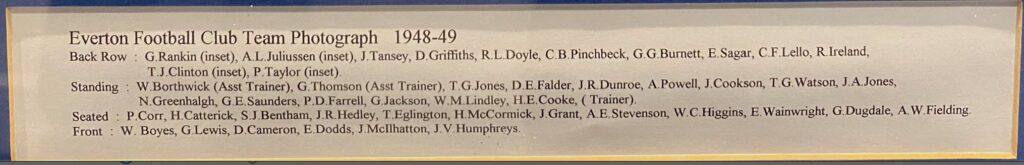

As a teenager, Gwyn was spotted by a Bangor City director and by sixteen he was turning out for the Cheshire League club’s first team at Farrar Road. He also gained Wales Youth (Under 18s) honours – in one match running with the ball from the halfway line to score against Northern Ireland in Belfast. Gwyn’s father pushed him; he could see the talent in his son and was desperate to further his career. He got in touch with a few footballing people hoping to secure a trial for Gwyn who had just turned seventeen in May 1948. Everton gave him a chance and liked what they saw. Their newly signed centre-forward would collect the princely sum of £7 per week in the season, but £2 less in the summer.

He took digs in Fazakerley and set about working his way up through the B, A and reserve teams, scoring regularly. Not tall (5’7”), Gwyn was pacy, direct and surprisingly good in the air. Like other young footballers of his era, his development was interrupted by National Service – he had two years with the army between 1949 and 1951.

Back home in Wales he had met and started courting Sheila Evans, from Rhostryfan near Caernarfon. She combined singing in local showbusiness productions with working in the family bakery business. With Gwyn being based on Merseyside, they’d meet roughly for dates in Colwyn Bay or Llandudno. Gwyn wasn’t the only sporting star in the family, brother Ken also impressed at Bangor City, earning a move to Walsall FC in 1954.

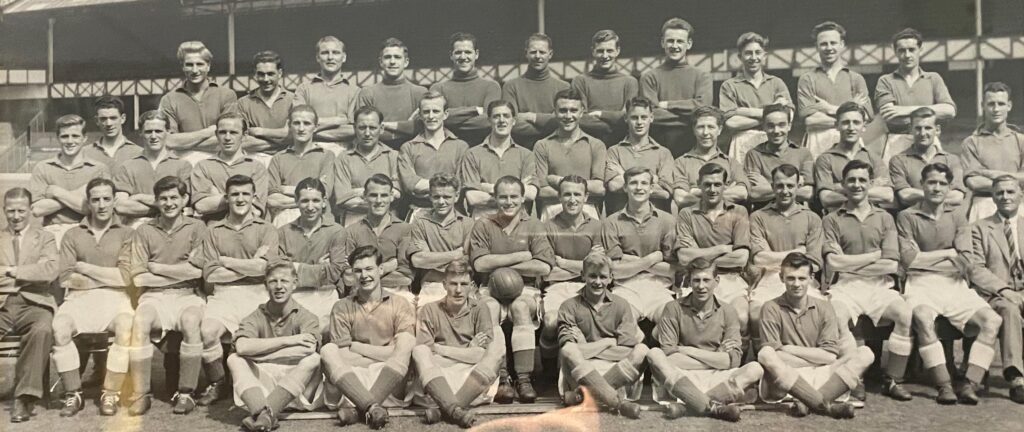

Having scored 17 goals in 14 second string matches for the Toffees, Gwyn was belatedly given a first team debut away to Bury in March 1952, while Dave Hickson dropped to the reserves. Gwyn was never particularly close to Hickson, perhaps due to the rivalry for the number nine shirt. The Shakers won 1-0, but Gwyn received cautious praise from the watching Liverpool Football Echo reporter Stork:

Lewis had very few opportunities but was certainly a menace to the Bury defenders…Lewis did manage to steer the ball into the Bury goal, but the whistle had sounded offside a second beforehand. Lewis had found Head a difficult obstacle in this, his first League game and he introduced one of two nice moves, but the line as a whole tried to be much too clever when a little more directness might have told its tale.

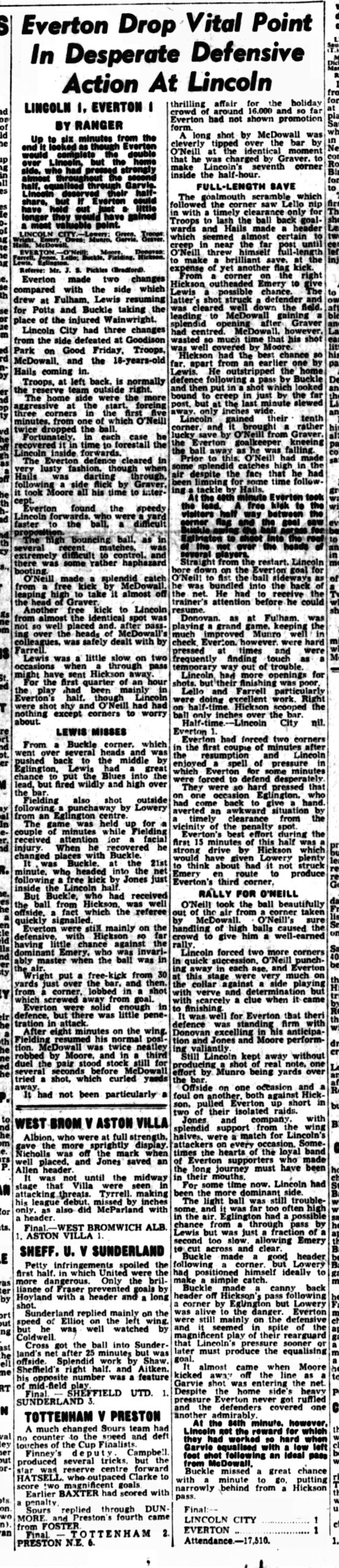

With the Cannonball Kid restored to the Toffees front line, the Welshman returned to the ’stiffs,’ waiting almost twelve months for another attempt to impress in the first eleven. When it came, in March 1932, it was an opportunity he grasped, scoring twice for a weakened team in a midweek 2-2 draw at Meadow Lane. His first was a header from a cute lob by Jimmy Tansey, while the second was a fine left-footed effort after picking up the ball 40 yards out, described by the Liverpool Echo, thus:

It was Everton who got the next goal, and it was Lewis again who scored. This was a top-class goal. The young Everton leader had to beat off three challengers as he ran through the middle. Then drawing Bradley from goal he calmly shot the ball into the net.

Dropped for the next match, he made a scoring return – a consolation effort in a 3-1 defeat by West Ham, with Hickson rested before the FA Cup semi-final. In spite of the goal, he was adjudged to have had a poor game and, once more, dropped out of the first team frame.

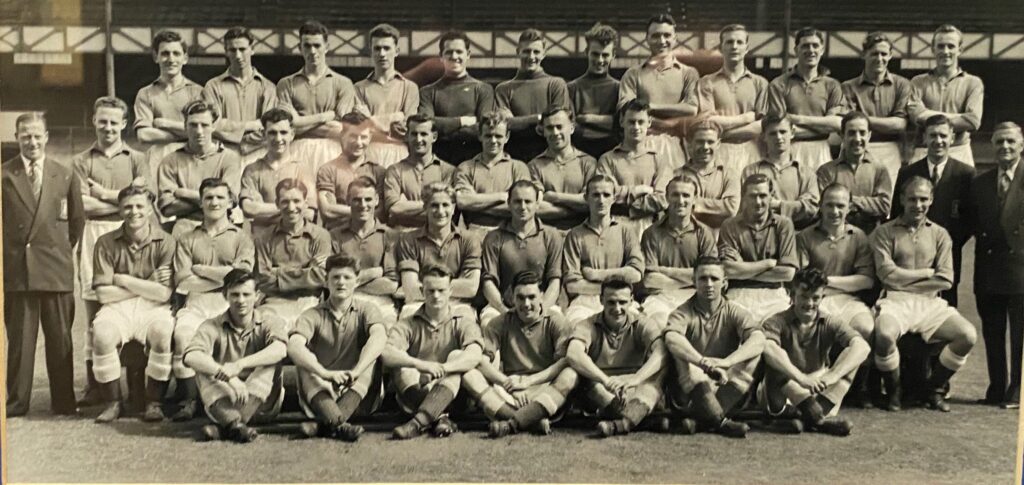

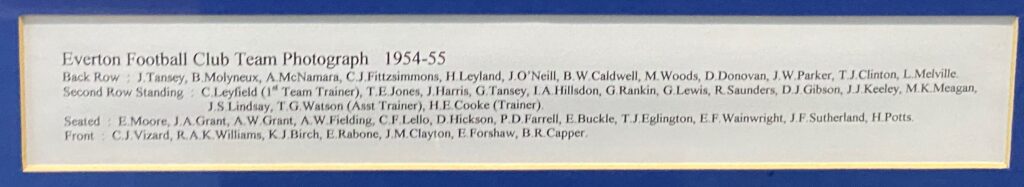

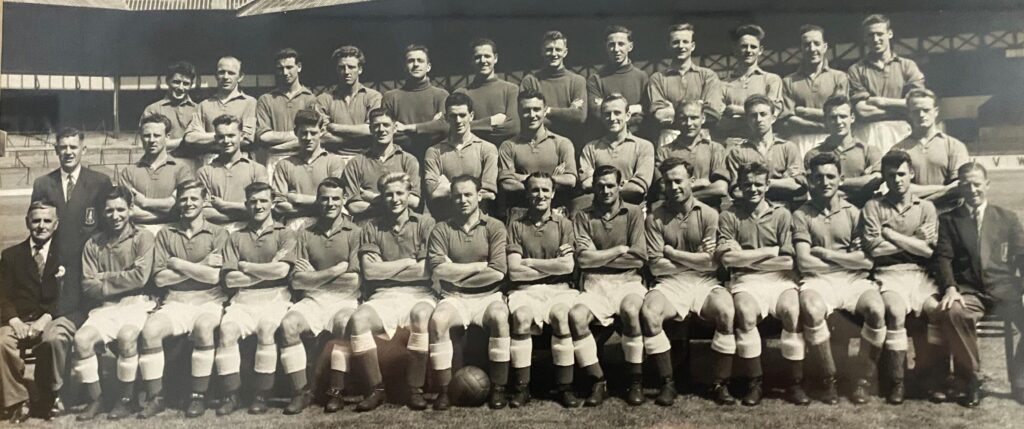

The following season, in which the Toffees gained promotion back to the top flight, he got a meagre three starts, scoring in two of them – one of which was an important 3-1 defeat of Lincoln City at Goodison during the run-in. He got his Division One career off to a good start in September 1954 with a goal in his first outing, a 2-2- home draw with Leicester City. He opened his account in the 29th minute with a neat finish after interplay with Irish duo Peter Farrell and Tommy Eglington. The Football Echo described the goal in these terms:

The move had its beginning well in the Everton half, when Farrell switched the ball out to the left flank; Eglington rounding Froggatt put in a comparatively short pass which Lewis took in his stride and rammed home with a grand shot just out of Dickson’s reach.

However, in the 50th minute, an agricultural challenge by the Foxes Jack Froggart left the goal hero on the ground, writhing in pain. The match report described the incident and the aftermath as Gwyn bravely battled on:

There was a quick call for a stretcher and the young Welsh boy, after having his ankles fastened together, was covered with a rug and taken off. After the game had again been stopped for over a minute for attention to Eglington the crowd roared its pleasure when Lewis returned to the field, and limping badly, went to outside left. This was a relief to everybody. Although at full strength numerically, Everton were handicapped for Lewis could not raise a gallop and Leicester for some time had been the more dominant side.

Having returned to the fray after fifteen minutes of treatment, Gwyn was a hobbling passenger, but with nine minutes left on the clock, skimmed the crossbar with a rasping drive. His other two selections that season came in poor defeats.

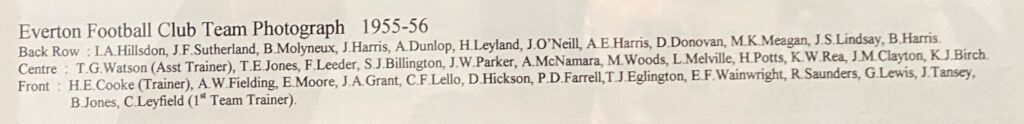

In his final season at Goodison Park, Gwyn made a solitary appearance. Dave Hickson had departed for Aston Villa, but the Toffees had a new exciting number nine breaking through in Jimmy Harris. It was of little surprise, therefore, for the Welshman to receive a letter from the club, dated 25 April 1956, advising him that he was being made available for transfer. Of course, in these pre-Bosman days, the club could still seek a fee to release him to another club; he was advised that £2,500 was the figure they’d be seeking. That summer he made the move to AFC Rochdale in the company of Jackie Grant and Eddie Wainwright for a combined fee of £2,500 (some way short of what Everton had been seeking). The key factor in the swoop by the Spotland club was that their manager, Harry Catterick, had once been a teammate of the Blues trio.

Deployed by Catterick at both centre-forward and inside-left, Gwyn made an excellent impression with the Division Three North outfit and was soon attracting suitors. He had other things on his mind, though, as he wed Sheila in Bangor in the autumn (Ken, by this point at Scunthorpe United, was best man), the couple setting up home in Rochdale. In February 1957, Chesterfield FC took the striker to North Derbyshire and he obliged by netting in each of his first three appearances for the Spireites. It was the beginning of a hugely productive spell, which had been held back by staying in the shadows at Everton for too long. Over four-and-a-half seasons, the Bangor-born man made 129 league and cup appearances, scoring 59 goals.

Gwyn finished his playing days with non-league Heanor Town and Sutton Town, turning out to help make ends meet, finally hanging up his boots at thirty-two. In 1964 he returned to North Wales, delivering bread for the in-laws bakery firm. Subsequently, he worked at the Ministry of Food, and later became a wages clerk at Austin Taylor in Bethesda. Sheila, meanwhile, continued working in the family business and carried on singing in local clubs, pantomimes, concerts and Eisteddfods.

In his free time, Gwyn liked his music and dancing – plus a game of bingo. The couple were members of Bangor Conservative Club. He used to like going for a walk with Sheila on the pier in the Garth district of Bangor. They would call in for a quick chat with T.G. Jones, who ran the adjacent newsagent shop, or have a pint at the Ship Launch pub. On Saturday afternoon, he would meet up with his close friends for a few pints at the Old Vaults on Bangor high street.

Sporting-wise, Gwyn played cricket for Menai Bridge into the 1970s (in the 1950s, he had turned out with Everton clubmates occasional cricket matches) but appeared to lose all interest in football. If his sons tried to ask him about his memories of turning out for Everton in front of 40,000 supporters, he appeared to have no great desire to share them – this quiet man lived in the present, rather than the past. As a spectator, it was rugby union that attracted his interest in his post-playing years. His sons, who also attended Friars School, showed some footballing promise and Gary did turn out for Bangor City reserves.

Gwyn was a heavy smoker for much of his life, favouring strong Senior Service cigarettes (also the choice of compatriot Roy Vernon) before switching to cigars, thinking they were less unhealthy. Not long after taking early retirement, Gwyn developed a brain tumour, the cancer then spreading to his lungs. It was aggressive and he was told that he only had months to live. In his final days he had the support of Marie Curie nurses in addition to his family. He passed away on 23 May 1995, three days after his former club won the FA Cup Final.

Before Gwyn’s schoolmate John Cowell passed away earlier this year, I chatted with him. He eulogised about Gwyn’s talent, regretting that he stayed at Everton for so long with so little first team action, thereby hindering a career of great promise. Nonetheless, Gwyn Lewis could look back with satisfaction on a remarkable goal record, wherever he plied his trade.

Acknowledgments:

Gary and Mark Lewis

John Cowell

Billy Smith, bluecorrespondent.co.uk

Steve Johnson evertonresults.com

enfa.co.uk