Obituary by Rob Sawyer

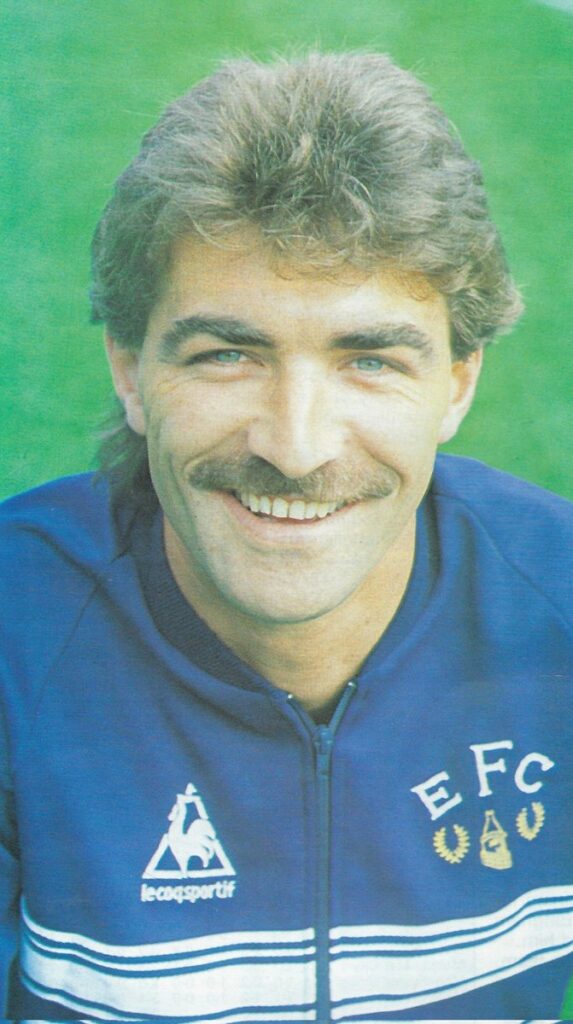

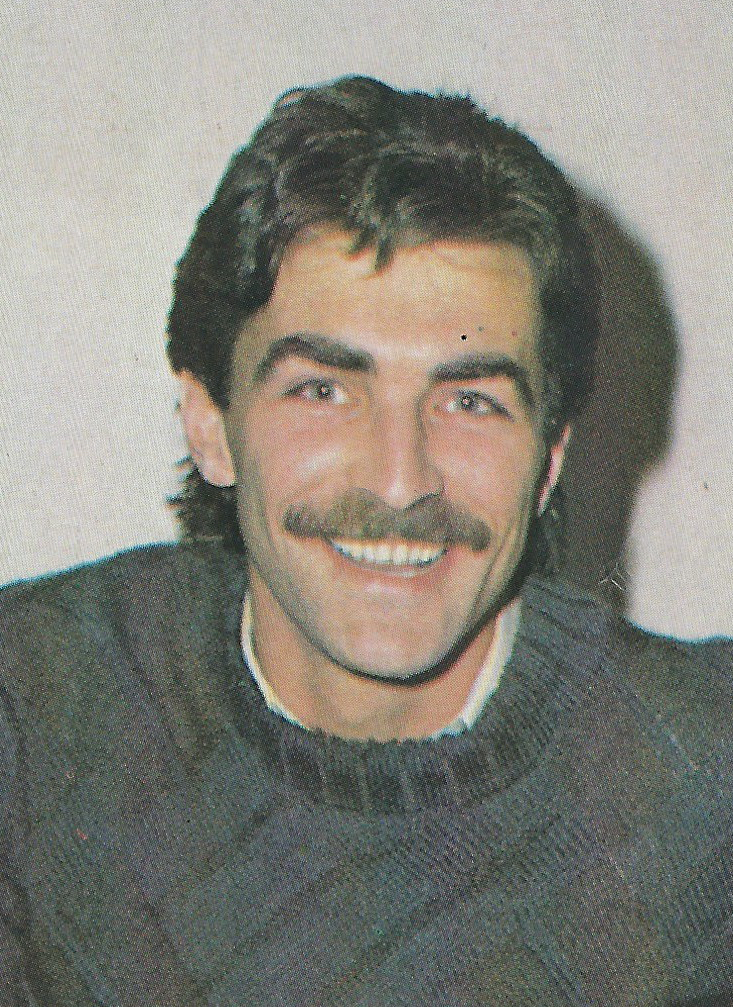

The recent news of the passing of John Clinkard at the age of seventy-one, prompted both great sadness and also fond remembrance of the role the physiotherapist played in Everton’s 1980s glory years. For many, he was better-known simply as ‘Magnum’ – more of which later – to others he was ‘Clinks.’

Raised in Kidlington, Oxfordshire, John attended Gosford Hill School and was a very decent centre-forward in the Kidlington Boys teams in the late 1960s. He made his way in the game as a physio at Didcot Town and Fulham FC, where one of the players in his care was Ronny Goodlass, who played for the Cottagers at the turn of the 1980s after a spell in the Netherlands. He also worked at Newport Hospital and a rehabilitation centre near Slough.

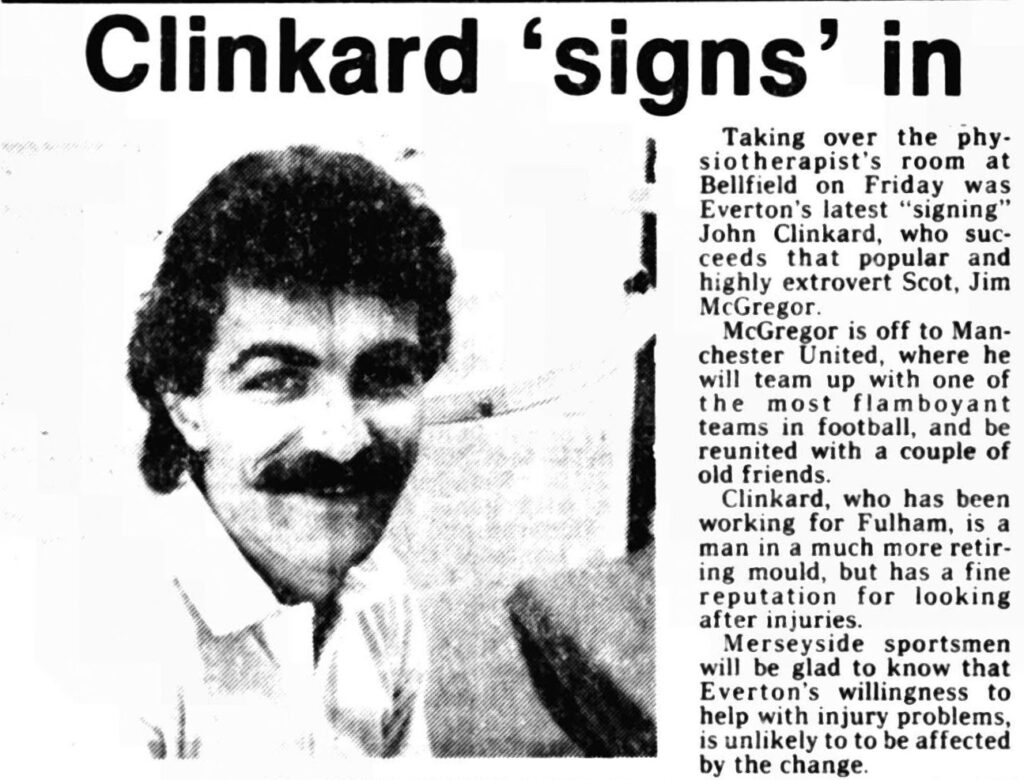

The departure to Manchester United of Jim McGregor, not long after Howard Kendall took the managerial reigns at Everton, created a vacancy for what would be only the Blue’s third official physiotherapist* after McGregor and Norman Borrowdale (previously, Harry Cooke had fulfilled that role as part of his team trainer duties, assisted by ‘blind masseur’ Richard ‘Harry’ Cook).

Kendall was tipped-off about John Clinkard by Terry Darracott, who had spent some time with him whilst having rehabilitation from knee issues. The former Everton full-back’s recommendation held some sway, and Kendall did further checks prior to offering the Fulham man an interview. In October 1981, it was announced that John would be moving to Merseyside, and specifically, Bellefield. At twenty-seven he was the youngest physio in the top flight.

In the 1980s, there was no medical science department at Everton – merely the physiotherapist, Club doctor Ian Irving, and the Club’s retained surgeon, John Campbell (both of whom John described as ‘superb’). Only occasionally might the physio have support from an assistant. Therefore, it could be an extremely demanding task – helping to get the walking wounded fit and back in action with the minimum of delay, while also working on the recuperation of players battling serious, long-term injuries, including the likes of Mark Higgins, Adrian Heath, Neville Southall and Paul Bracewell.

The 1984/85 season saw John administering running repairs to many players during the 63-match campaign, whilst also overseeing the long, painful recuperation period for Mark Higgins and Adrian Heath. Heath’s race to get fit for the start of the 1985/86 season, after the knee injury sustained in December 1984, when in the form of his life, meant that John only had two weeks off between the seasons. They had been working together six days a week for six hours. John was in attendance when Adrian underwent surgery on the damaged knee, stating, “It’s as if you are waiting for the result of an operation on a close relative. The club doctor and myself felt numb afterwards. Inchy is a popular lad and a bit special to all of us at the club.” Seeing the forward come off the bench to score in the Charity Shield match at Wembley must have made their shared sacrifice feel worthwhile.

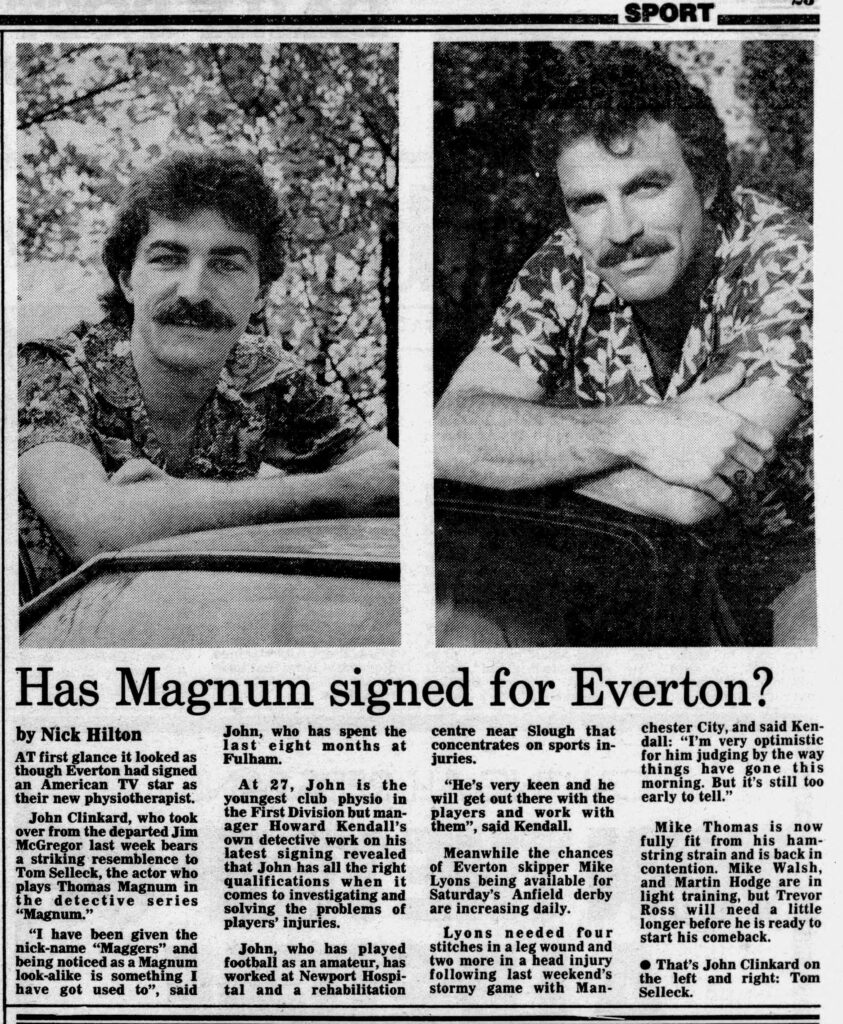

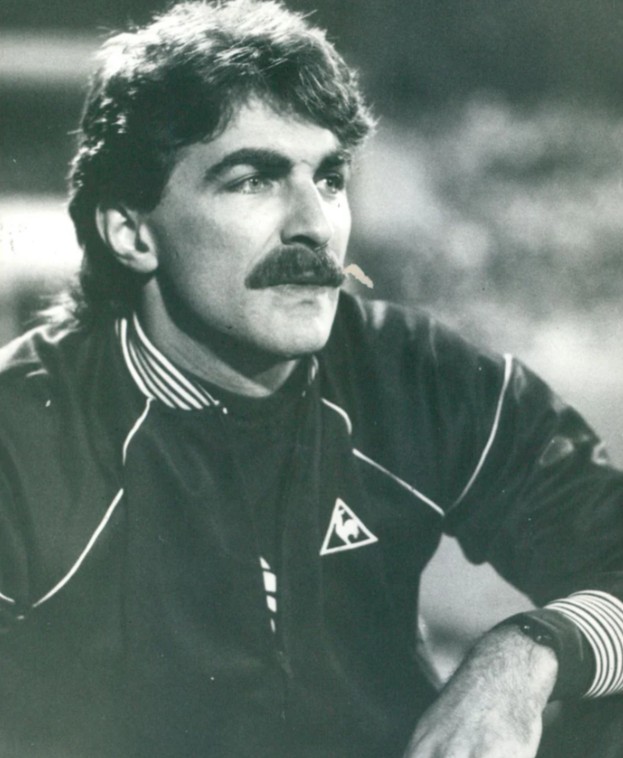

Heath, who spent so much time with the physio on his long road to recovery, told Simon Hart in the latter’s book, Here We Go: “The lads loved Clinks. He was a big, good-looking guy and he loved the fact that he looked like Magnum. People would put his picture in for Tom Sellick lookalikes [competitions] and we’d be at the training ground and they’d be delivering a fridge or something he’d won.” John would confess to finding Higgins’ enforced early retirement very upsetting. He travelled to London with the stricken centre-back, to receive the specialist’s advice that he must hang up his boots (on a more positive note, Higgins was able to restart his career with Manchester United after surgery).

Naturally, with his good looks and moustache, comparisons were rapidly drawn with Tom Sellick, starring in the role of Thomas Magnum PI in the eponymous American TV series. He was soon dubbed ‘Maggers’ by players and staff (failing that, it was ‘Clinks’), and ‘Magnum’ by supporters. It is something he embraced, appearing at Kennedy’s Furniture Centre for the launch event of their ‘magnum’ three-piece-suite. He also did the honours, resplendent in white tuxedo and bow tie for the opening of the Magnum Wine Bar in a Lathom hotel.

The 1985/86 season saw no let up for the man overseeing the treatment room, with Peter Reid missing a significant chunk of the season, and Derek Mountfield playing with a persistent knee complaint. He would recall the sinking feeling he would get when sat in the dugout when seeing another player pull up with an injury, “Kevin Sheedy’s injury at Luton was a typical example. As soon as he pulled up, I knew that he’d be out for three or four weeks. When that happens, I feel quite depressed for the rest of the game – but in general I’ve never been down for too long because we’ve had success.”

Colin Harvey, who was coaching the reserves at the time of John’s arrival on Merseyside, prior to being elevated to joint first team coach in the late autumn of 1983, retains great respect for his late colleague:

“John had a lovely way about him – he was a people person who could work with players. Treatment rooms are notoriously hard places, and you have different characters in them. Some players want to work hard to get back fit quickly, others are more lackadaisical. John had a lovely manner about him and got them in a good mood, so they were working without realising it. He knew how to manage them all differently, in as nice a way as he could. Along with Les Helm, he dealt with them as well as anyone I have known. It helped that he looked a bit like Magnum, as well – I think he was even better looking than him! When we played Oxford United once, his dad came down to the team hotel to meet him. With his white hair, moustache and similar personality, he was what we imagined Clinks would be like in 30 years time.”

John was quoted in 1986 as saying, “It takes a good 12 months to get to know all of the individuals and their different ways, but once you know your patients, half the job is done. As time goes by, you also learn by your errors of judgement. Diagnosis of injuries is a series of intelligent guesses and the more experience you have, the more accurate you are likely to become.”

For Colin Harvey, John’s expertise paid personal dividends as well as for the squad, as he explains: “I had my first hip replacement operation in 1984, and in the afternoon after training John would have me in there. After me taking a hot bath to loosen up, he’d start on me. He would give me a series of stretches to do, and hooked my leg with wires into different positions. That hip is still working now, forty-two years later, whereas the one on my right side has been redone twice. So that good hip is John’s legacy for me, personally.”

Come the summer of 1986, he was getting the Toffees’ world-class goalkeeper Neville Southall fit again after a terrible ankle injury sustained on international duty on the Lansdowne Road pitch. He likened the injury (which involved a dislocation of the ankle and ligament damage) to that experienced in a road traffic accident or a heavy parachute landing. The Welshman had this to say after learning of John’s passing, “John was a charismatic human with fabulous knowledge. He was just the right man for Everton. Nobody could have been better suited to a great team and wonderful staff. Without him, I’d never have got as good as I did after my injury.” Reid, who returned to action early in the New Year, paid this tribute on the Everton FC website, “What a man! All the players loved him and trusted him completely when he was with us. He was a brilliant character, and I’ll always remember him with great affection.”

Away from his Everton duties, Clinks gave a series of talks on physiotherapy at Marine FC, and also trained and played for a football team in the Wigan and District Sunday League called the Masons Arms. Naturally, when the side lost a cup final, he received the customary ribbing on his return to Bellefield on the following Monday morning.

The 1986/87 championship-ship winning season was a miraculous team effort, with the physio more than playing his part – you could go as far to say that it was his ‘Magnum Opus’. When the first ball was kicked in anger, five international players were sidelined with injuries (Bracewell, Reid, Southall, Stevens and Van den Hauwe) plus Neil Pointon and Derek Mountfield (knee surgery). Kevin Sheedy would succumb to a cartilage issue in January, requiring surgery, while Graeme Sharp missed a significant chunk of the season with an ankle issue.

John reflected on the period just before Christmas 1986, when the players were queueing up to get into the treatment room: “Six or seven senior players, and up to three schoolboys, were competing for seven beds! It was a challenge coordinating everything and keeping on top of the treatment. I’ve never met a player, yet, who enjoys being injured. I see them at their lowest ebb and my job is to lift the happy type. I like a laugh and a joke and don’t take life too seriously. You have to work out who you can push and who you must nurse along. Some look to you to give them guidelines and advice. Others give you more feedback.”

Paul Bracewell’s was, perhaps, the most problematic injury to overcome, as no-one (and no scanner) was able to get to the bottom of the chronic ankle pain the England midfielder had been experiencing since a crunching challenge from Billy Whitehurst. In the end, John arranged for the midfielder to see a specialist in California, who spotted and removed a bone fragment that came off the ankle and implanted itself in the tibia. Bracewell would finally return to first team action in the 1987/88 season and become a regular starter again from the autumn of 1988, following further surgery. Clinks would subsequently pay fulsome tribute to the midfield dynamo, “Paul is one of the best and bravest pros I have ever worked with. He is a credit to himself and his profession.”

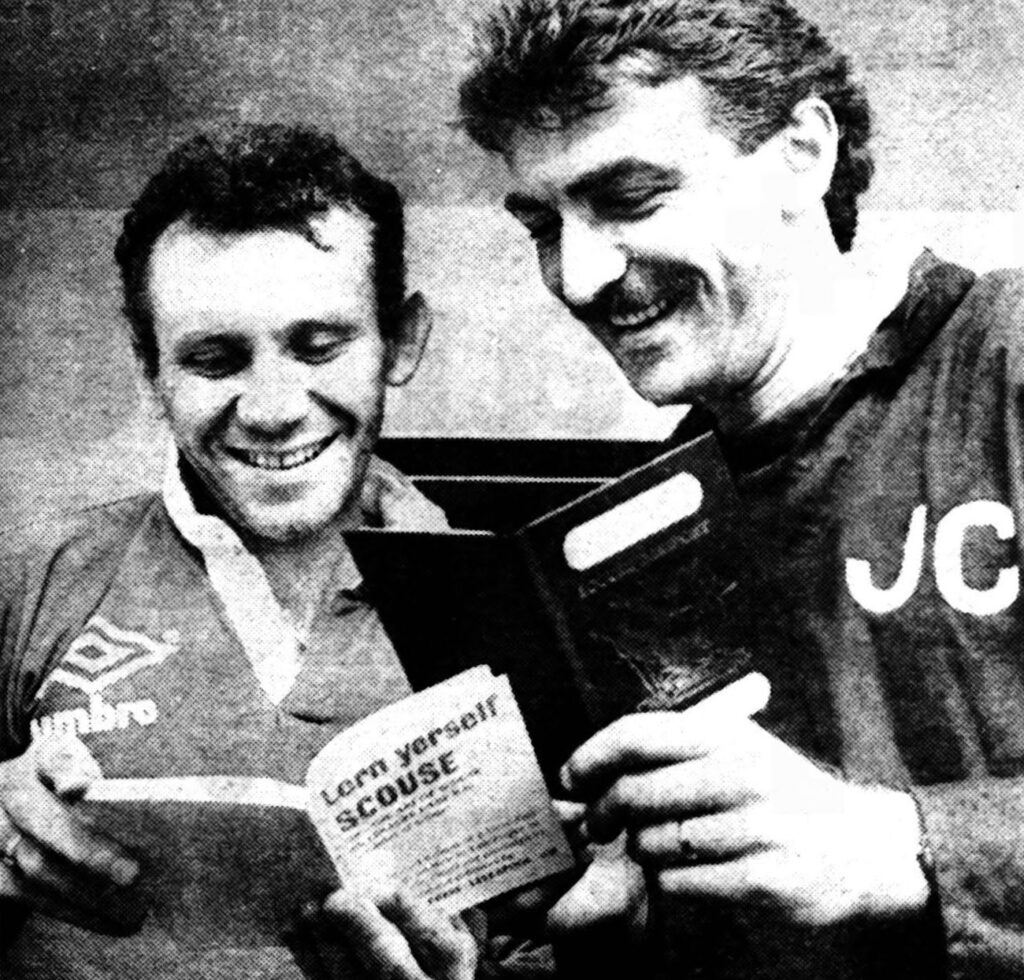

With Howard Kendall and Mick Heaton moving on in the summer of 1987, John became the sole non-Scouser in a first team set up that was composed of new manager Colin Harvey, Mike Lyons, Terry Darracott, Peter Reid, Graham Smith and Chief Scout Harry Cooke. Darracott would continually tease the physio about his inability to speak with a Liverpool accent. In August of that year, Ken Rogers reported in the Liverpool Echo that the backroom team had clubbed together to buy him a ‘Scouse passport’ plus a Lern Yerself Scouse phrasebook. He took it in customary good heart, promising to practice and try out a few Liverpudlian expressions.

In the summer of 1988, John informed the club of his intention to return to his home county, ending a highly successful association just shy of seven years. Chris Goodson, who had previously deputised for John in some Central league matches, moved from Wigan Athletic to take on his duties. John told the local press of his reasons for leaving, “All of my family are in Oxfordshire…I’ve got a young family growing up – Hannah who is nearly two and Lauren who is only seven weeks – and obviously I would like my father to see more of them. The opportunity arose to join Oxford United, so I took it. I know it won’t be the same as working at a big club like Everton. I’ve been with the Blues for close on seven years and made so many good friends. From day one the atmosphere has been tremendous, but I just feel this move is right for my family.”

Colin Harvey would later confess, “John ran a really tight ship. He was badly missed after he left, he had been part of the unit, with a really unique style. Ironically, it would be former Liverpool centre-back Mark Lawrenson, who was embarking on a managerial career at Oxford United, who took John on at the Manor Ground. When Lawrenson left the club, the trusted physio remained, under the incoming Brian Horton, staying on under Denis Smith. In all, he had in excess of ten years with the Yellows, also running his own private clinic in Abingdon. Horton described John as ‘a top physiotherapist and, most of all, a top man.”

At the Manor Ground he kept a ‘bottle bank’ containing body parts removed from players in his care – including the offending piece of bone from Paul Bracewell’s ankle, Peter Reid’s cartilage, and scar tissue from Terry Curran’s knee. It was a nice parallel with his Goodison predecessor Harry Cooke, who kept similar jars in his inner sanctum in the main stand.

John was a popular guest at the 1984/85 reunion event linked to the gala screening at St George’s Hall of the Howard’s Way film. More recently, he fought a brave battle with cancer.

When Evertonians reflect on winning two league titles, an FA Cup and a European Cup Winners’ Cup, they will, understandably, think of the band of brothers on the pitch – but the non-playing staff in the dugout, ‘Clinks’ among them, will not be forgotten.

Everton FC Heritage Society sends its condolences to John’s nearest and dearest at this very difficult time.

Rob Sawyer

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Colin Harvey and Neville Southall for sharing their memories of John.

Excellent tribute Rob to one of the very best in class and the era. John Clinkard was everything the role entailed a perfect role model for any young up and coming physio who wanted to work in football.

An ever encompassing role of the club physiotherapist that was much than strapping ankles and massages.

Showed how vital player care is and the importance of the soft non clinical skills are in doing the job and helping to keep the show on the road that ‘Show’ was playing matches, fielding players and hopefully winning. Sadly missed RIP John

Along with Mick Heaton he was integral to the backroom team that complimented Kendall and Harvey. Although we are in different times the only other physio that I can remember by name at Everton was Baz Rathbone, who was also a big personality. The words from former players are testament to Clinkard the man and the professional. May he rest in peace

Whilst manager of didcot town in Hellenic league and up to southern premier league, John was our go to expert , whilst working close with our club physio mark Robert’s , his knowledge and guidance was a huge help visiting the club on a weekly basis, working with not only first team but right through our youth set up as well , my children and anyone who he could help , most players continued to see him after they either left the club or retired , all while still working at his own practice . Great man and is sorely missed . Rip John . The world is not so great without you

Thank you so much for this outstanding tribute to an outstanding man also a true professional. He was my brother in in law back in those halcyons Everton days. John had a lovely way with him a special aura he used this attribute to breed positivity during treating those injured players. RiP John Clinkard

Hi Rob, Firstly, this is beautiful, accurate and a superb tribute to an absolute gentlemen. Well done.

I first met “Clinks” when I was 16, I was about to become a YTS 2 yr (scholar these days!). Just prior to my apprenticeship (May 1993) I suffered a horrible knee injury… Aged just 16, and at the very start of my apprentice years (June 1993) Clinks attended with me and my Father to the Chiltern Hospital in Great Missenden (near High Wycombe) to a pre-op assessment (he lived in Stadhampton at the time), and then attended the same day of the operation and then subsequently at my home the day after.. This for a 16 y/o…… Such was his care, personality and love for his players… As it happens, he has treated many hundreds/thousands of players/people more important than me, but nethertheless, I wholeheartedly remember..

met him on subsequent occasions, often at the Snooty Mehmann restaurant in Coxfirire, never woukd yu meet a nice person..

Paul Byles