Rob Sawyer

“The undisputed king of centre-halves – a living object lesson of the superiority of brain over muscle.”

(Contemporary newspaper description of Johnny Holt)

Time passes, and with it go first-hand memories of footballers who bestowed greatness on Everton. T.G. Jones is widely cited as the club’s finest centre-half, with the next generation of fans also holding Brian Labone in the highest of esteem. But let us not overlook Johnny Holt, the Little Devil – without equal in his era in the art of defending, and a bedrock of the First Kings of Anfield.

John Holt entered this world at 3 Hope Street in Blackburn on 16 October 1866 – the second of four children born to Thomas and Susan (née Ditchfield). Census records show the family moving a couple of times in the area, ending up in Church, near Accrington, with John following his father into stone masonry (Thomas would die in 1888, at just 44). He later recalled first learning the art of football through matches played in the cobbled streets, with an empty salmon tin acting as an ersatz ball.

With fellow future Everton star Edgar Chadwick, he had attended – and played football for – the Commercial School on Duke’s Brow. His sporting progression took him to King’s Own FC (a club which also produced such well-known players as Jimmy Forrest and Herby Arthur – later the Blackburn Rovers goalkeeper).

Blackburn was a hotbed of football, and every week fifty or sixty young football enthusiasts used to leave Blackburn railway station on their way to assist teams in neighbouring towns and villages. Johnny’s second club was Church FC, and it was while playing for them against Clitheroe that he first made the acquaintance of the great Hughie McIntyre of Blackburn Rovers, the second Scotsman to cross the border for football purposes (the next being Fergus Suter who recently featured in the Netflix drama, The English Game). He moved to Blackpool St. John’s FC in 1884, his next stop being Merseyside two years later, when Bootle FC acquired his services.

An ambitious club, arguably the leading one in the area at this time, the Hawthorne Road outfit harboured ambitions of joining the Football league, which was being formed to create a regular competition between top clubs. However, Anfield residents Everton FC had similar aims, and their last-ditch lobbying got them included in this exclusive new club in the spring of 1888. In late May of that year, a benefit game was staged at Anfield for Mike Higgins, one of the Toffees loyal servants, contested by a combined Everton-Bootle-Stanley XI and Mr Sudell’s team (primarily players from Burnley). The Everton big-wigs clearly liked what they saw, and overtures were made to the Bootle defensive pivot. Johnny’s business at that time had taken him to Wrexham, so keen were the Evertonians on securing him that they followed him there and signed him on in a hostelry.

The club had also acquired the services of Nick Ross (Preston North End), Edgar Chadwick (Blackburn) plus William Warmby and Jack Keys (Derby County). The Liverpool Mercury noted: ‘Such a team can only be maintained at an enormous expense, but the executive can rest assured that the public will gladly assist them in their ambition to possess Liverpool of champion exponents of the game.’ Bootle could only lick their wounds at the loss of their star centre-half. The club was admitted to the second tier of the Football League in 1892, but folded a year later, having failed to get sufficient numbers of spectators through the turnstiles.

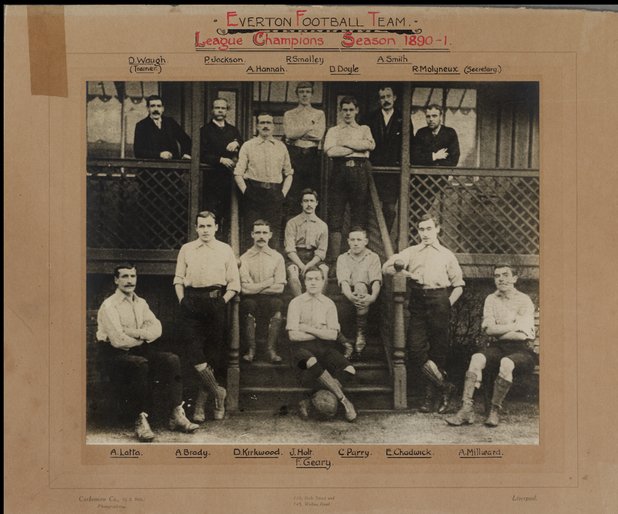

Johnny Holt seated on the chair in the centre

For Johnny, his Football League debut against Accrington on 8 September 1888, marked the beginning of a magnificent decade of service – 253 appearances in all – for the Everton cause. He was a key member of the Toffees team which won the Football League in the 1890/91 season – missing just one game (a defeat) and captained them for the following season, the Toffees’ last at Anfield. In the off-season he would return to his hometown – the 1891 census capturing him lodging in Church and giving his occupation as a stone mason.

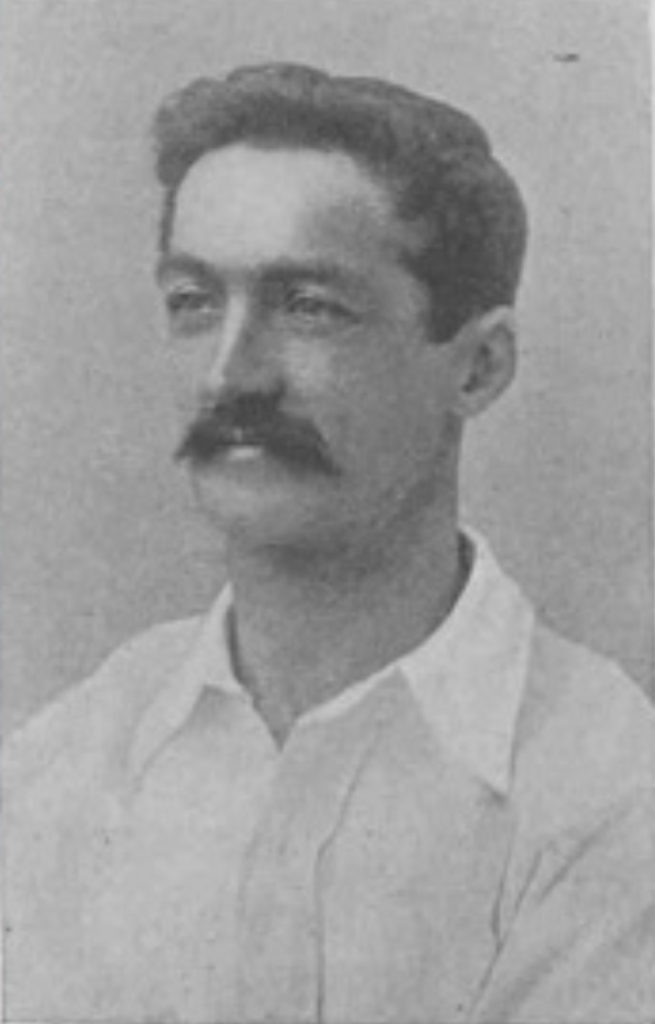

Johnny Holt at the front

In terms of overcoming his height disadvantage at centre-half, he argued that the ball was on the field to be kicked, so why shouldn’t he be the person to kick it? He was blessed with an uncanny ability to read the play and make well-timed interceptions and tackles. Victor Hall, of the Liverpool Football Echo, reminisced in 1925:

‘Holt broke up every attack he played against. This is no figure of speech; he shattered every attack – robbed it, plundered it, battered it, and ridiculed it, until it became limp and paralyzed, and generally gave up trying to get past this magician, who seemed to know just where you were going to “try” to put the ball, and to get in the way of it, and take it away with him. Even if you changed your mind – and didn’t get it there – he changed his mind too, and got to the other place first.’

Once the ball was won, recalled Hall,

‘Very few people ever saw Johnny Holt robbed of the ball – he took it along with him. Not fast, mind you, just whenever he wanted to take it – while his forwards sorted themselves into their proper positions. And then he “gave” it to them with an air of “Now! Go on, while I go back and play in the centre.”’

And if the ball was in the air, ‘Little Johnny’ could rely on his barely credible, prodigious leap, which Hall described, thus:

‘He generally stood a few yards from the centre-forward, who, conscious of his own height, waited for the goal kick to come to him. Holt made no movement until the ball was in the air and dropping; then, like a flash, his body shot up into the air. Most often his hands rested on the startled centre’s shoulders for an instant of time – getting an “impetus” or a “poise” – whichever he needed. And his head headed the ball; often two feet higher in the air than the six-foot centre below him. Holt’s heading was miraculously exact – he seldom headed a pinpoint out of direction, but he headed to his own forwards, and straight away his side were attacking again!’

Then there was the Holt ‘X Factor’: a mastery of gamesmanship. In short, Johnny was without equal when it came to hoodwinking referees, in ‘butter wouldn’t melt’ fashion, and winding-up of opposition forwards. In his 50th anniversary history of Everton, Thomas Keates described Johnny thus;

‘The fascinating robbery of giants, and amusing mastery of diminutive Johnnie Holt, were a serio-comic feature of the games that made him a favourite. He was an artist in the perpetration of clever minor fouls. When they were appealed for, his shocked look of injured innocence was side-splitting.’

Victor Lewis, in the Echo, confirmed that the play-acting and ‘simulation’ of modern football is nothing new:

‘When an unsuspecting referee saw a little foot getting suspiciously [like] initiating a trip, and “blew” accordingly to investigate, he would find to his amazement, when he got to the spot, that it was Holt who was on the ground, writhing in apparent anguish, while an indignant and bewildered forward was volubly protesting that he was the injured party.’

W.I. Bassett, in a 1910 article titled Things That Are Not Football, showed grudging admiration for the centre-half’s proficiency in the dark arts of the game:

‘We hear a great deal from opponents of the Association Code, or from those whose preferences are for the Rugby code and for other pastimes entirely, of the regrettable tricks, to which players identified with the dribbling game descend. The great thing in football is to be a good sportsman. Years ago, we had several players who used to do the most daringly illegal things in the most charming manner possible. Johnny Holt, of Everton, was perhaps the greatest exponent that ever lived of the art of doing a slight illegality without receiving the penalty. Johnny would use is hands freely; in fact, he would literally climb up opponents ingeniously and head the ball at a great height. But he did it so neatly that no-one ever felt offended. Every man knows when he is doing right and when he is doing wrong. Let him keep a sportsmanlike demeanour, and he won’t go far wrong, and if he does go a trifle out of the straight line, well, the deviation will be so slight that people will say: “Oh, he didn’t mean any harm; he’s a good sportsman.”’

That is not to say that he always kept on the right side of match officials. Two separate accounts refer to Johnny coming to blows with a referee – however the details, and even the matches referred to, differ, so the tales could be exaggerated, or apocryphal. Nonetheless, this is what former referee John Lewis said in 1903:

‘I do remember seeing a fight on one occasion, it was on the Accrington ground. Everton were the visitors, and little Johnny Holt disputed the ruling of the referee, and it ended in a brief bout of fisticuffs between them.’

He was tough, too, being able to take the knocks as well as dishing them out. His only sustained period of absence from the Toffees line-up came after a series of injuries, sustained at Nottingham Forest in October 1895. Their description, in The Athletic News, underlines not only Johnny’s toughness, but also the brutality of football in the late 19th Century:

Quite a series of accidents in which Holt was always the victim, then commenced, and they terminated very disastrously for the little player. At the outset he was severely bobbed in the face by the elbow of Rose and his nose was broken, so I am given to understand. His left shoulder was also evidently severely damaged, but, game as a bantam, he was quickly on his feet. Twenty minutes from the start however, he collided heavily with McInnes and on this occasion he was so badly injured that he had to be carried off the field. He returned before the interval and played out the first half, but a careful medical examination then revealed the fact that the tip of his collar-bone had been knocked off, and he was promptly conveyed to the hospital.

The rather partisan Nottingham Daily Post gave this account:

Queer little Johnny Holt, one of the most interesting and amusing of half-backs, came in for a warm time. Early on the game was stopped on account of his having been slightly injured, and he had not been going long again before he was unfortunately bowled over by McInnes. This was evidently a more serious affair than the other, for blood streamed from the victim’s forehead, and there was nothing for it but to carry him from the field. Sometime before the conclusion of the first half he was, however, back again as active and adroit as ever, but with his white knickers bespattered with blood.

Such was his club form that international recognition came his way – first he was an unused sub on his home club ground when England defeated Ireland 6-1 in March 1889. A year later (15 March 1890), he became the second Everton player to wear the England shirt, when selected for his country against Wales at The Racecourse, Wrexham. In a bizarre twist, England had two fixtures on the same day and his clubmate, Fred Geary, debuted in the other match, which kicked-off 35 minutes earlier. His tally wearing the three lions badge would rise to nine during his spell on Merseyside. The cap he valued most was the one bearing the dates 1891-93-94-95-95, a memento of the fact that he represented England against Scotland on five consecutive occasions. One description of his performances in the shirt of England read:

‘Holt has seldom been seen to greater advantage, and the judicious manner in which he fed his forwards, and at the same time tackled the opposing advance guard, was simply marvellous, and the little wonder was generally voted to be the smartest centre-half who has yet “fought” for his country.’

He felt that his greatest international outing came against Ireland. England had two men injured, and Johnny spent 45 minutes covering the left full-back and centre-half positions jointly. He said that he was never more devoutly thankful when the final solo on the whistle was played than he was on that day. A noted scribe wrote, ‘Holt was head and shoulders (figuratively of course) above the rest of the halves.’

He had little time for the nickname given by certain sections of the press. To them he was ‘Daddy Holt’ – an apparently ironic reference to him being the daddy on the pitch, in spite of his lack of inches. So irked was he by the moniker that he asked to Everton directors to stamp on it – as evidenced by this board minute from November 1892:

J. Holt: Complained about Nuggets appearing in the papers about him & the use of the name Daddy Holt.

Resolved the Sec. write to the Express & Football Field re. same – and that we will do all in our power to remedy the matter.

Blessed with a sardonic sense of humour, and straight face, Johnny’s abilities to wind-up people off the pitch matched those on it. Fellow England international player, Billy Bassett touched on Johnny’s gift in his newspaper column in 1909:

‘Footballers in my day were past masters of the gentle art of pulling each other’s legs. Even I was supposed to possess some little accomplishment in this direction, and this was partly due to the fact that I could look abnormally grave, and keep my face straight on all occasions. But Johnny Holt was the king of them all. Johnny used to get at people in an inimitable way. I have heard him tell not only youthful Internationals, but experienced ones, all sorts of tall stories, and apparently, they have been gulped down.

‘I remember once in 1892 the Association magnates were so pleased with our play in the international that they decided to keep us in Scotland over the Sunday, and give us a treat by taking us on a little tour. We had some good fun in the carriages as we drove to Balloch. After we had all been teased in turn, Johnny Holt got at Dennis Hodgetts in a really startling way. It will be recalled that we [West Bromwich Albion] had just beaten Aston Villa in the final of the English Cup. This suddenly flashed across Holt’s mind. Here was an opportunity too good to be lost. “How many medals have you got, Dennis?” said he, with an air of almost childish innocence. Dennis told him. “How many times have you played in the Birmingham Cup final, Dennis; have you got your Birmingham Cup medal for this year?” and so on. Hodgetts naturally fell into the trap, and was only too glad to converse freely in regard to the number of trophies he had secured. “Have you got your English Cup medal for this year, Dennis?” said Holt sweetly, and you should have seen the smile which went round, for the company recalled how overwhelmingly disappointing the result had been to the Villa. Hodgetts flared up a little, and, of course, that made matters worse. But he was soon all right again.’

Sadly, for Johnny, the Toffees could not follow the 1891 title win with further senior honours – although there were near misses – notably a runners-up spot in the League (1896) and two FA Cup final defeats, in 1893 and 1897. The latter would go down as his bitterest experience in the shirt of Everton. The 2-3 loss to Aston Villa at the Crystal Palace stadium went down as a cup final for the ages, with the Toffees attacking excellence undermined by defensive frailties, with goalkeeper Bob Menham having a difficult match. Asked what it felt like to participate in an ‘English Cup’ final, Johnny said: ‘The chief feeling is one of over-anxiety, a feeling which frequently leads you to do the wrong thing when you particularly desire to do the right one.’ To balance that opinion, he pointed out that he enjoyed playing in front of a big crowds as, in much the same way as actors, he fed off performing before a large and appreciative audience.

A year after that disheartening defeat in South London, Johnny, at 31, felt jaded and ready to walk away from football. His final match for Everton was a home defeat of Sunderland, rounding off the 1897/98 season, before emigrating to start a new life in Canada, setting sail from Liverpool on 21 April.

Reaching Quebec, he selected a farm – football wasn’t on his ‘to do’ list. However, he had not been in his new home long when a deputation from the local football club requested that he play for them in a match against the Indian College team. The secretary acted as spokesman and said that they had heard indirectly that Johnny could play football. Oddly for someone making a pitch, he went on to say that they were about sick of ‘Britishers’ who arrived claiming to be able to do anything but fared little better than the locals. Johnny listened quietly and then replied, ‘But I did not tell you I could play.’ His follow-up statement, that he never played for less than five guineas a match, doused their hopes of recruiting him as a footballer. Instead, he offered give his services as a cricketer. This was accepted and he made several respectable totals as a batsman.

For unspecified reasons, Johnny was called back from Canada to England in the late summer of 1898. Needing to earn income, he found himself without a football club, but still tied to Everton through his Football League registration. He had hoped and expected that Everton would waive any fee, as a mark of gratitude for services given. He was mistaken: ‘It cost Everton nothing to secure my services. I played for them for nine years, and then when I wished to make a change, they asked £300 for my transfer. This practically barred me from playing in the north, for naturally a man could not be worth that to any club, after having played so long. I may state that New Brighton offered Everton £135 for my transfer, and Burnley were prepared to pay £200, but neither offer came to anything.’

It is true that the Toffees sought offers of £300 for Johnny, but did drop this to £150 – New Brighton Tower coming up just short with their bid. Glasgow Rangers thought that they had their man in August, but it fell through after Johnny only found out in newspaper reports and via telegram that a deal was ‘done’. He took umbrage and refused to co-operate.

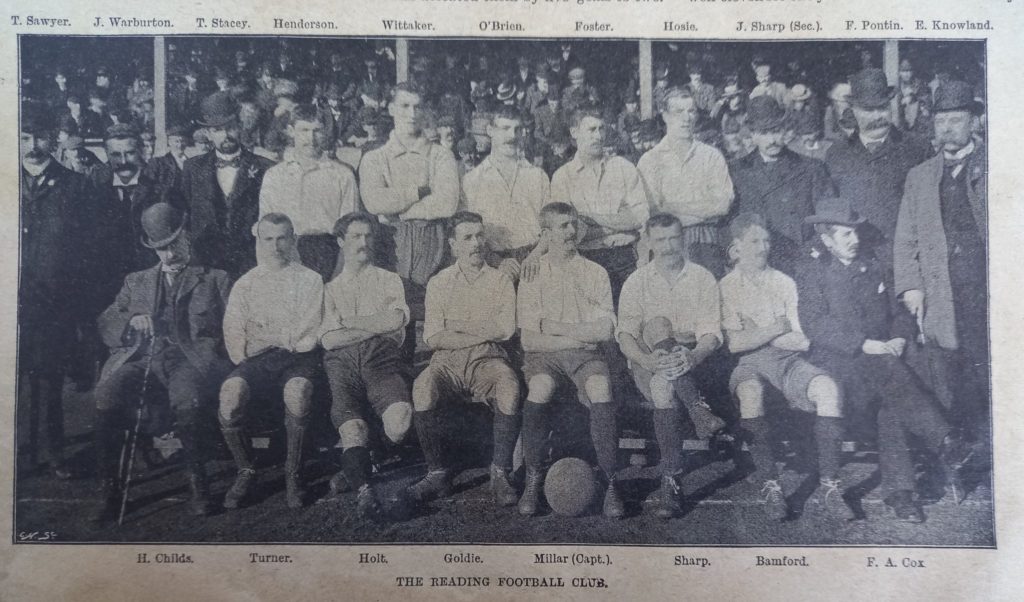

Johnny Holt – front row, third from left (photo: Chris Lee)

In October the club-less man took matters in his own hands, accepting an approach from Jimmy Sharp, the secretary-manager of Reading FC. The club’s Southern League status circumvented the registration issues – depriving the Toffees of a transfer fee. The Blues held onto his League registration, though, and were still hoping to recoup £100 for his services in 1900 (his registration with the Football League was finally expunged in 1903). It would be two years before the Toffees had a top-level specialist centre-half to take on Johnny’s mantle, Tom Booth arriving from Blackburn Rovers.

Johnny Holt – front row, centre (photo: Chris Lee)

It was believed by observers that Johnny’s powers were on the wane, The Berkshire Chronicle casting doubt on the wisdom of Reading’s acquisition: ‘The advisability of signing on such an “old hand” is extremely doubtful.’ On the contrary, he enjoyed a new lease of life with the Berkshire outfit – revitalising a team which had struggled, and earning a call up for a Football Association party to tour Germany in 1899. He looked back fondly on the four matches played there. Dining in a hotel on the tour, he was passed a note written by a wealthy American tourist, which, when opened, bore the words: ‘Three cheers for Little Tich’ (a nod to a diminutive music hall star of the era). He won his tenth, and last, international cap on 17 March 1900 when taking to the field in Dublin at the age of 33 years, 152 days.

The Blackburnian carried on playing for The Biscuitmen – attributing his enduring fitness to the restorative and weight-controlling powers of Turkish baths. In the summer of 1902, the veteran applied to be granted amateur player status, thereby enabling him to continue playing while also being a newly-elected director of the club (rules forbade a director also being a professional player). The application was declined (or deferred for a year) so this appears to have forced his retirement from playing.

In April 1901 he had married Thomasine Bodle (eleven years his junior) at St. George’s Church in Tilehurst, Reading. The wedding was quiet, on account of the bride’s brother being away, fighting in the Boer War. The newlyweds honeymooned in London. Johnny’s occupation at the time of the nuptials was given as a pawnbroker & jeweller. His age was shown, incorrectly, as thirty (rather than thirty-four). Not long afterwards, he entered into a prosperous mineral water manufacturing company (Messrs. Humphries & Holt). The firm was dissolved in 1910, but Johnny continued in that line of business for over twenty years; he also appears to have had an interest in The New Inn, an establishment owned by Thomasine’s family (Thomasine would recall taking the large mirror down from the wall behind the bar, every time a fight broke out). Away from work, the former footballer enjoyed photography and air rifle shooting.

He continued to support Reading FC in any way he could – in October 1910, he was reported to have received a ‘fine reception’ from the spectators at Elm Park when refereeing a friendly match between Reading Reserves and Reading Victoria. He was not forgotten on Merseyside, either, and was an esteemed guest at the club’s golden jubilee dinner held in April 1929 – receiving one of the most prolonged ovations of the night, when introduced to the attendees.

Johnny and Thomasine’s only child, Douglas, worked for Cable and Wireless, inheriting Johnny’s sense of adventure by also crossing the Atlantic, working for his employer in South America. Contracting TB, he was rushed back to Britain, and sent to convalesce in North Wales – going on to marry Mary Bowen, one of his nurses there.

In his later years Johnny – living with his wife at 228 Tilehurst Road in Reading – suffered with balance issues and, latterly, mental deterioration, which he, and family members, attributed to the frequent heading of excessively heavy soaking-wet footballs. His final four month were spent in Brighton County Borough Mental Hospital, at Haywards Heath. He died on 18 December 1937, as a result of pneumonia-linked myocardial degeneration .

The present-day family remain immensely proud of their forbear, with several members being devout Evertonians.

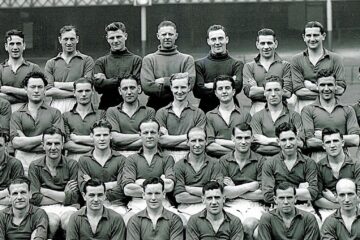

in Brighton, in 1936

in Brighton, in 1936

Sources:

Sincere thanks to Johnny Holt’s family, for assistance and permission to use images etc.

Chris Goodwin (England Football Online)

Billy Smith: https://www.bluecorrespondent.co.uk

James Corbett, The Everton Encyclopedia

Thomas Keates, History of the Everton Football Club (1878-1928)

Chris Lee – Reading FC history website: https://www.chrisdlee.com/

Various newspapers, including:

The Athletic News

Liverpool Mercury

Liverpool Daily Post

Liverpool Echo

Nottingham Daily Post

The Reading Standard

Reading Mercury

The Berkshire Chronicle

Football and Sports Special (1909)

PS When Holt won his last cap, I make his age 34 years 341 days. But that’s because I’ve always had his DOB as 10 April 1865. That’s wrong, is it? His family confirm he was born on 16 Oct 1866?

Thanks for your time with this.

Hi Chris,

Yes, to confirm his DoB was 16 Oct 1866.

Best regards

Rob Sawyer