A talk given by author Spencer Vignes to the Everton FC Shareholder’s Association

Leigh Richmond Roose

Leigh Roose was born in a small village called Holt which lies just on the Welsh side of the border between England and Wales a few miles outside Wrexham. As a youngster he took to goalkeeping like a duck to water, perfecting his art during kick-abouts in Holt and while at university in Aberystwyth where he went to do a science degree. While he was in Aberystwyth he also played for the top local side, Aberystwyth Town, with who he won a Welsh Cup winners medal and his very first international cap playing for Wales, against Ireland in Llandudno. But by 1900 he had become what you might call a big fish in a small pond, and so he did what many a young provincial twenty something in search of fame and fortune has done – he moved to London, where he worked as a hospital assistant during the week and played football on weekends for a team called London Welsh, though London Welsh didn’t last long as by now dozens of top clubs were all desperate for him to play for them.

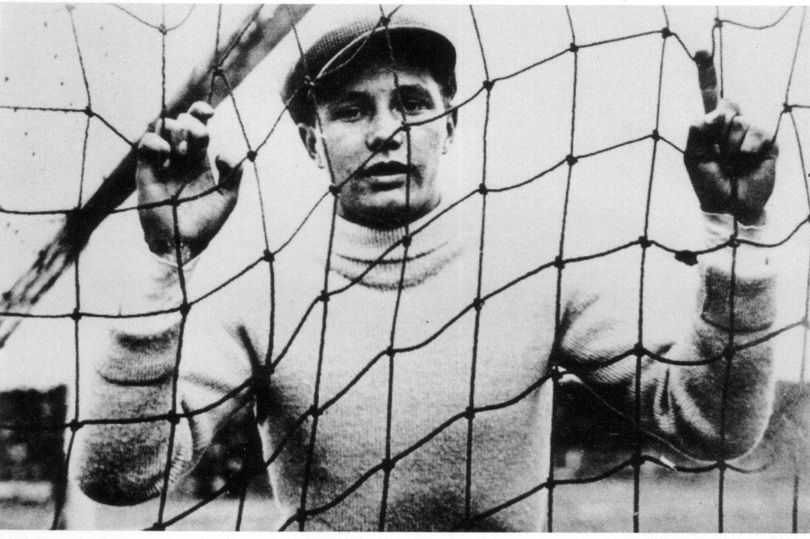

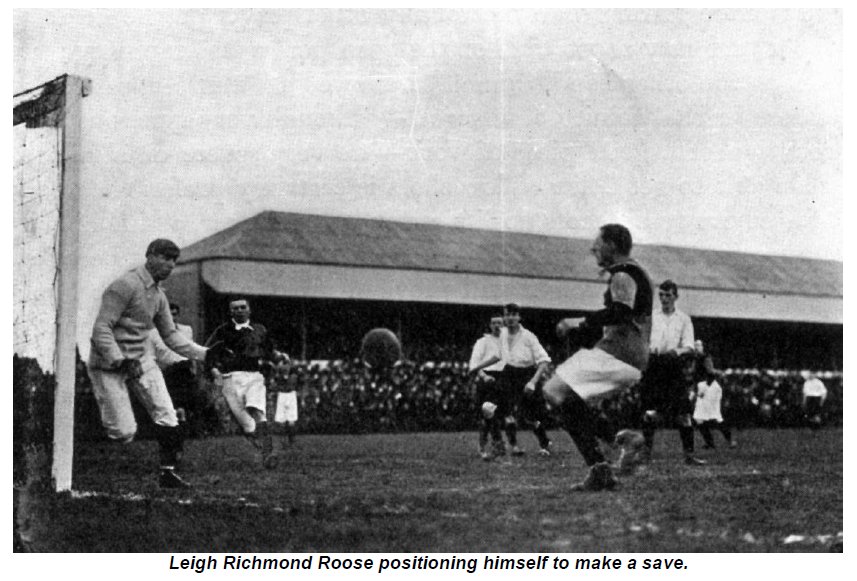

Over the next decade Leigh established himself as the best goalkeeper in Britain by a distance, playing first for Stoke, then Everton, then Stoke again before moving on to Sunderland – and incredibly he did it all as an amateur player, working during the week in the hospitals of London and travelling on Saturdays from the capital to wherever his team of the moment happened to be playing. When Wales won their first ever Home Nations Championship in 1907 Leigh was the rock on which the team was built. When the Daily Mail came up with its world eleven to take on a team from another planet, Leigh Roose was the first name on its team sheet. Along the way he developed quite a reputation as a showman. While he was at Stoke he would hire a hansom carriage to take him from the railway station to the ground, insisting on driving the thing himself at speed through the city streets with groups of supporters chasing after him. During lulls in matches he would regularly do gymnastics on his crossbar and tell jokes to the crowd.

He was also an exceptional practical joker. There was one time when Wales were playing in Ireland and Leigh turned up in Liverpool to catch the boat with his hand heavily bandaged. He told everyone ‘Don’t worry, it’s only a couple of broken bones, I’ll be able to play’. Those who knew him were a bit suspicious and, sure enough, that night a couple of his teammates peeped through the keyhole to his room and saw him take off the bandage and exercise the fingers. The following day, the day or the game, he appeared again with the bandage on and the telegraph wires began to hum with news that the Welsh goalkeeper was going to play with two broken fingers. Of course once play had started he calmly unwound the bandage and went on to play a blinder.

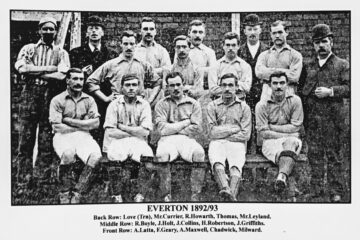

Leigh played for Everton for just the one season, the 1904/05 campaign. That was the season when Everton looked as though they were going to achieve a league and cup double, only to suffer double disappointment by losing in the semi-final of the FA Cup and suffering the mother of all blowouts in the league. In January they were top. With six games to go they were still top. However, their final three games had to be played in the space of just four days and the task proved too much. They lost two of the three and ended up finishing runners-up to Newcastle after which Leigh had a minor falling out with manager William Cuff and ended up going back to Stoke City.

Leigh’s glory days as a player continued right up until 1911 when he broke his arm badly during a Sunderland versus Newcastle match. He recovered to play again but many felt he was no longer the player that he had been, that maybe the bottle and courage that had helped make him the outstanding goalkeeper he was had been knocked out of him. Sunderland clearly felt so because he never played for them again, although he did keep goal for both Aston Villa and then Arsenal during the 1911/1912 season before finally retiring from top class football.

Of course I don’t need to tell you that in 1914 war broke out between Britain and Germany. Because of his medical background Leigh joined the Royal Army Medical Corps and was sent to work in a makeshift hospital in France which formed part of what was known as the casualty evacuation chain, treating the injured before arranging for their evacuation back to Britain. He stayed in northern France until March 1915 before being recalled to England in readiness for another foreign tour of duty, this time at Gallipoli in Turkey. I don’t know how much you know about what happened on the Gallipoli Peninsula but it pretty much all boiled down to this – Britain thought that picking a fight against the Turks would open up an eastern front to the war breaking the stalemate that had built up on the western front in northern Europe. Now the generals expected the Turks to turn and run at the first sight of a British battleship. Of course the Turks didn’t do that and fighting got bogged down at Gallipoli where it went on for eight horrible months before the Allies were forced to evacuate. Once again Leigh was part of the casualty evacuation chain taking the injured away from the Peninsula to places like Egypt.

By early 1916 Leigh’s regular stream of letters home had dried up and his family began to fear the worst. They made enquiries and it appeared that Leigh was in fact missing presumed dead. Nobody however, not even the Royal Army Medical Corps, seemed to know whether he had gone missing before, during or after the evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, yet as the weeks turned to months, and there was still no word, that became immaterial. It seemed as though Leigh wasn’t coming back.

And that appeared to be that as far as the Leigh Roose story was concerned….until four years later that is, when Leigh’s sister Helena and her husband John, a former Welsh rugby international, were having dinner one evening at Twickenham after an England v Wales international. They were sitting round the table talking with various people including a famous cartoonist of the time from the Daily Mail called Tom Webster. At some point Leigh’s name came up in the conversation and Helena said how sad it was about what had happened to him at Gallipoli, at which point Tom Webster said that Leigh couldn’t have died at Gallipoli because he’d played cricket with him in Cairo after the evacuation. This revelation was a real bombshell for Leigh’s family and it got them thinking. Had he died afterwards? Maybe he was still alive?

So what really happened to Leigh Roose after Gallipoli? Well nobody ever really knew until a few years ago when, without wanting to sound like I’m blowing my own trumpet, I managed to find out while doing my research for this book. Leigh DID in fact join the Royal Fusiliers after the evacuation of Gallipoli. However, due to a clerical error when he joined up, it seems that Leigh’s surname was miss-spelled so it became ROUSE instead of ROOSE. That meant the name ROUSE appeared on all military paperwork relating to him from then on. It didn’t matter how hard Helena Roose searched for Leigh ROOSE. She was always going to come up against a brick wall because that name never existed in the records.

Leigh ended up returning to France in July 1916 to fight with the Royal Fusiliers at the Battle of the Somme. He fought throughout the summer of 1916 into the autumn, winning a Military Medal for his actions during one skirmish in which he bravely kept on fighting – without a gun – despite his clothes having been burned by German flamethrowers. His presence in the trenches by all accounts created quite a stir – imagine being called up for action and finding yourself standing shoulder to shoulder with Gary Lineker and Andy Gray, or other larger than life sportsman such as Andrew ‘Freddie’ Flintoff or Ian Botham.

Leigh was 38 when he went to the Western Front so he came to be regarded as something of a father figure by many of those around him who were young enough to be his son. He was also something of a welcome distraction from the daily grind of what was going on all around, giving talks to groups of soldiers during breaks from the front about his life and playing career not to mention the behind-closed-doors activities of one Marie Lloyd. This is what one soldier, Second Lieutenant Gerald Bungey, wrote in his personal diary after meeting Leigh – “Had tea today with none other than Leigh Roose. An immense and extremely funny man. Told him I had seen him play against The Arsenal in 1910 and that he should have prevented the first goal. With a smile he pretended to draw a pistol and, in effect, shoot me!”

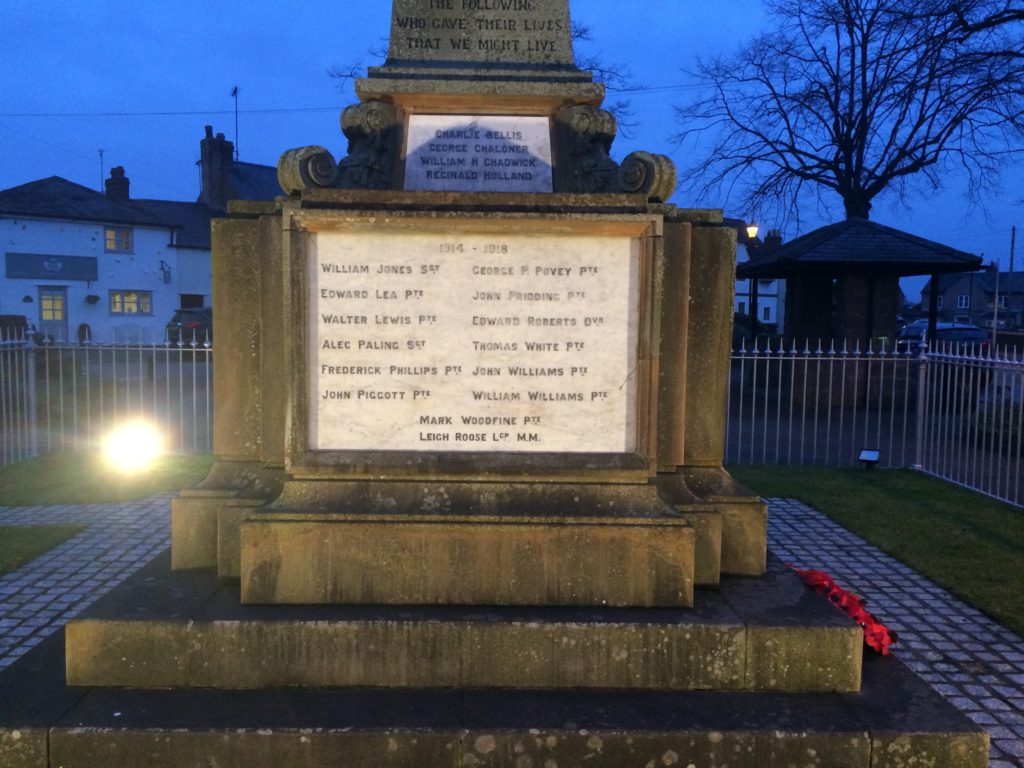

Leigh was killed at some point on Saturday 7 October 1916 during an Allied attack on German lines near a little village called Gueudecourt. No body was ever found – it was either blown to smithereens or sank in the mud where he fell – and it’s because no body was ever found that he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial in northern France which, as some of you may know, is a huge war memorial baring the names of 72,000 British and South African soldiers who have no known grave. Except of course that the name on the memorial isn’t Leigh ROOSE – it’s Leigh ROUSE!

Now as a result of my book plus several letters written by other admirers of Leigh, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which is the organisation which looks after Allied graves, has now agreed to change the spelling of the name on the Thiepval Memorial. The catch is that they’re only going to do it when the panel on which Leigh’s name is inscribed becomes worn and needs replacing. I was out at Thiepval three years ago and the panel looked fine to me then, so it could be many more years before Leigh ROUSE becomes Leigh ROOSE, and I think that’s a crying shame. Many of those who would like to see the spelling changed aren’t exactly getting any younger – in fact Leigh’s nephew Dick died only last year aged 103. It would have been nice if the spelling had been changed in his lifetime, but unfortunately it wasn’t to be.

So why has Leigh Roose remained forgotten for so long? Well the confusion surrounding the spelling of his name obviously has something to do with it, as does the fact he was just one of I think around 900,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers who died in World War One. Why mourn a footballer you admire from afar when your father, or brother, or brothers, weren’t coming home? Of course there was no Sky TV or Match of the Day in Leigh’s time, so there’s ALMOST nothing in the way of moving pictures to remember him by – I say ‘almost’ because one piece of film featuring Leigh does remain, taken at a Wales versus Ireland game at the Racecourse Ground in Wrexham in 1906, and that’s believed to be the oldest surviving film anywhere in the world of an international football match.

I hope that by writing the book I’ve helped put Leigh back on the map over 90 years after his death. One thing I am glad about is that his family now know what happened to him. Apparently Dick Jenkins, Leigh’s nephew, spent his last few days on planet earth in bed having extracts of the book read to him by his son. As far as I’m concerned that alone made all the time and effort I spent researching and writing the book worthwhile.

Spencer Vines

………………………………

Lecture llustrations by Mike Royden

EFCSA Forum Evenings – see ToffeeWeb for more info

www.toffeeweb.com/season/08-09/comment/fan/article.asp?submissionID=10928

www.toffeeweb.com/season/09-10/comment/fan/article.asp?submissionID=10231