Rob Sawyer

In the sweltering early afternoon June heat of Estádio Jalisco, Guadalajara, England’s right-back slumps to the ground. Lying prone, he is approached by Brazil’s number ten, the great Pelé, who proceeds to lift his opponent’s leg and push the foot back in an attempt to alleviate the symptoms of cramp.

Pele (10) of Brazil tends to cramp-stricken Tommy Wright (14) of England after sustaining an injury during their Group 3 match at Estadio Jalisco, Guadalajara, Mexico, 6 July 1970 (photo; Neil Leifer)

This display of sportsmanship at the highest level of sport, at Mexico ‘70, was captured by photographer Neil Leifer and is one of the defining images of Tommy Wright’s stellar career for club and country. For a period in the late 1960s, he had established himself as the finest English right-back, ironically, vying for that honour with his Toffees clubmate Keith Newton. Like Newton, Wright might never have been there in Mexico, competing at the zenith of world football, had he not been for an inspired positional switch to defence, as a young player.

Tommy, who we lost on 20 January at the age of eighty-one, had had nine years as an Everton first-teamer, and would have been expected to continue delivering consummate performances in the number two shirt, were it not for a debilitating knee injury sustained in 1973. Colin Harvey, Derek Temple and Mike Trebilcock are now the only surviving members of the Toffees’ 1966 FA Cup-winning team. Of that pure-footballing 1969/70 squad, only the aforementioned Harvey, plus John Morrissey, Joe Royle, Roger Kenyon, Alan Whittle and Tommy Jackson are still with us.

Born 21 October 1944 in Liverpool and raised in the Norris Green district, Thomas James Wright was one of ten children – nine boys (all sports mad) and a girl. He had shown considerable promise as an inside-forward for Monkton Road County Primary School and at Croxteth Secondary Modern. He was selected to play for Liverpool Schoolboys, and on one occasion, Lancashire Schoolboys. For the former, he would line up in the 1959/60 season alongside Tommy Smith (Wright at inside-right, Smith at inside-left), with whom he would go on to enjoy duels in club colours and night outs when off duty.

This exposure in youth representative football brought the Norris Green lad onto Everton’s radar, but rather than joining as an apprentice, manager Johnny Carey signed the fifteen-year-old school-leaver on amateur terms, with the teenager given employment at the Littlewoods organisation, which was tightly connected to the football club. Naturally, Tommy was thrilled to sign for the team he had supported since childhood, watching heroes at Goodison like Tommy Eglington and Dave Hickson since the early 1950s.

A month Tommy’s junior was another aspiring footballer, Colin Harvey, who joined the club at roughly the same time. They immediately bonded, as Colin recalls: ‘We joined Everton at basically the same time. We hadn’t met before; he was very quiet, but something clicked and we became really good friends, and it stayed that way for years. We did everything together at that time. He didn’t have a bad bone in his body; he was dead honest with everything he did. He got injured in games a few times for being too honest. He was very brave and a really nice, uncomplicated lad who became an outstanding player’.

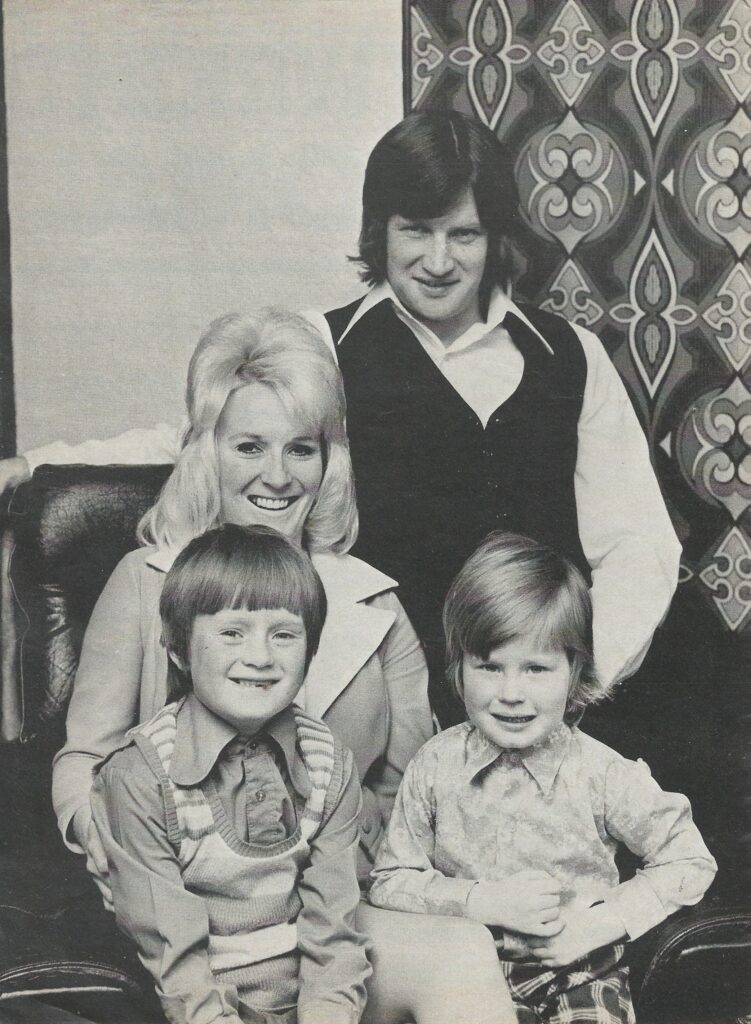

Naturally, Tommy turned to Harvey when choosing a best man for his marriage to seventeen-year-old Gwen Williams at Bootle’s Salvation Army Citadel on 3 July 1965. Tommy never learned to drive, Colin would give him a lift to and from training while Gwen would become the designated driver in the Wright household which, by the early 1970s, consisted of Tommy, Gwen and sons Gary and Andrew living in a pre-war detached house in Aigburth. Ironically, for a man who would jet far and wide on England duty in the late 1960s and 1970, Tommy was a bad flyer, so family holidays tended to be restricted to Wales (where they honeymooned) and the Isle of Man. Tommy would become a regular guest of the Manx Toffees supporters group when holidaying on the island.

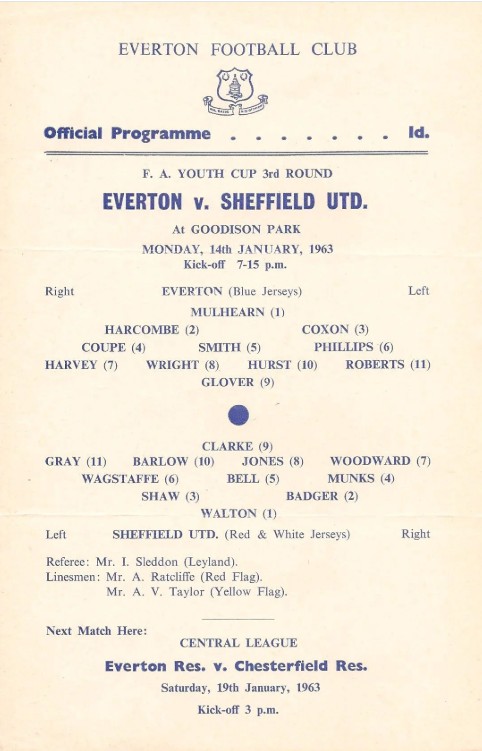

As a young footballer, Tommy worked his way up from the B (fourth) team to the A team, earning a professional contract at eighteen. The first mention of him making an impression in Everton colours was in a December 1962 FA Youth Cup defeat of Huddersfield Town, in which Tommy netted twice. Paul O’Brien, reporting for the Liverpool Echo and Evening Express, noted that the number eight ‘showed a welcome flair for finding open spaces.’

In the A-team he would line up with the likes of fellow forwards John Hurst and Gerry Glover, but there seemed to be little prospect of Tommy making the grade until the pivotal moment when the 19-year-old was tried in a different role. Gerry Glover recalls: ‘I played quite a few times with Tommy and he really wasn’t going anywhere. Then, thanks to the genius of Harry Catterick, who must have seen something in him, Tommy was playing right-back and was magnificent.’

The precise circumstances of Tommy’s positional switch from forward to full-back are somewhat hazy, with several slightly differing versions recounted over the years. Here, we’ll go with an account Tommy gave to Charles Buchan’s Football Monthly magazine a few years later:

‘In an Everton junior practice match I was asked to play in that position [right-back]. I appeared to take to the position like the proverbial duck to water, but I was still surprised when from the sidelines, the Boss (Mr. Harry Catterick) and the then coach Tommy Egglestone began to call out instructions to me. The fact that they considered me worthy of their attention was a big morale booster and after a spell of coaching in the basics of defensive play, I had four or five games at full-back in the “A” team before being promoted to the Central League side.’

So, what made Tommy so well-suited to wearing the number two shirt? When researching this article, supporters and former teammates have consistently told me about his impressive pace, diligence, honesty, bravery and positional awareness. Colin Harvey would also point out that, for a relatively short lad, he was blessed with a natural spring when jumping for headers. It was clear that Tommy was no hard man, but he would never shirk a tackle when up against some of the toughest nuts in the land. And, typical of Tommy’s character, everything was done to a high standard, but with the minimum of fuss.

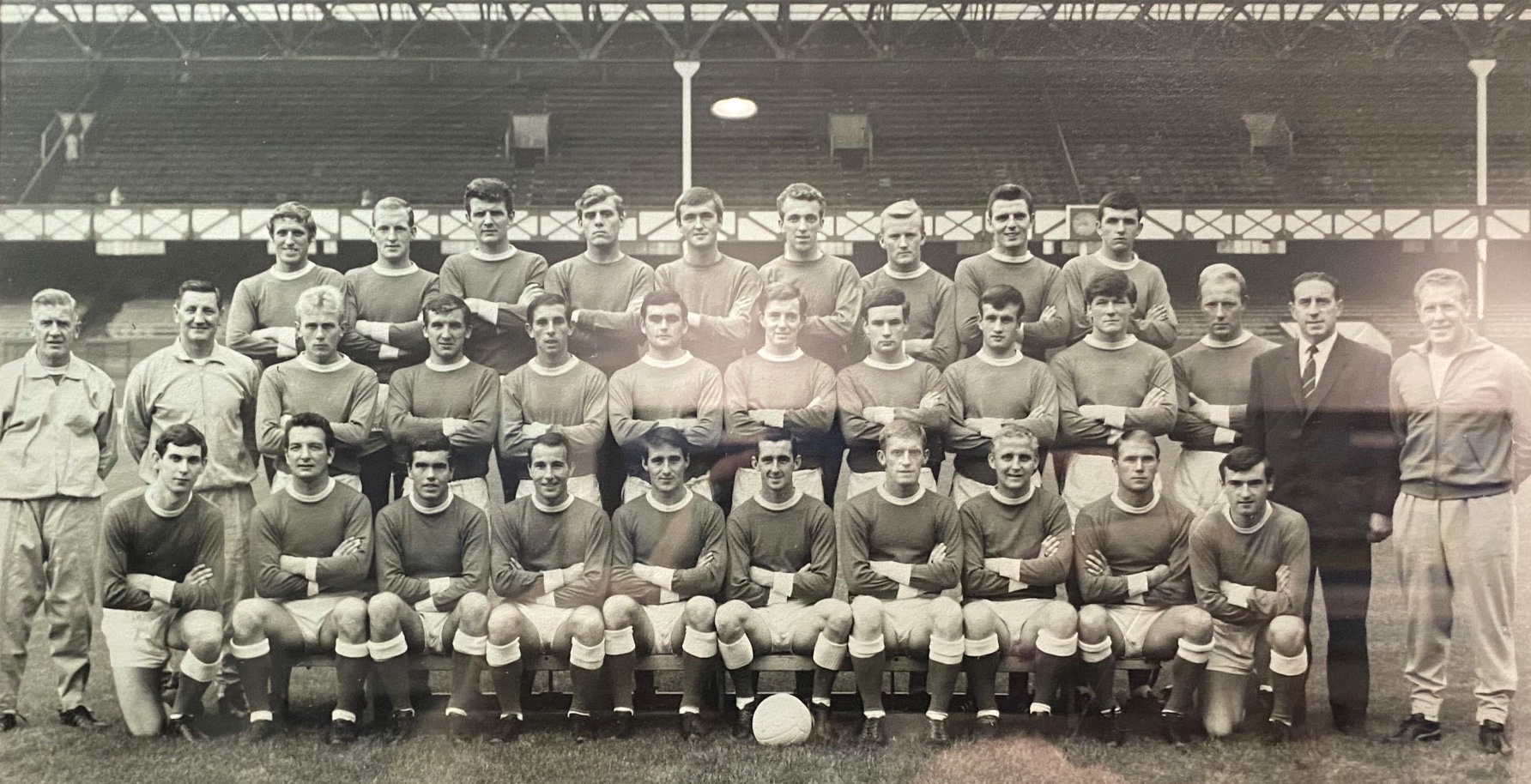

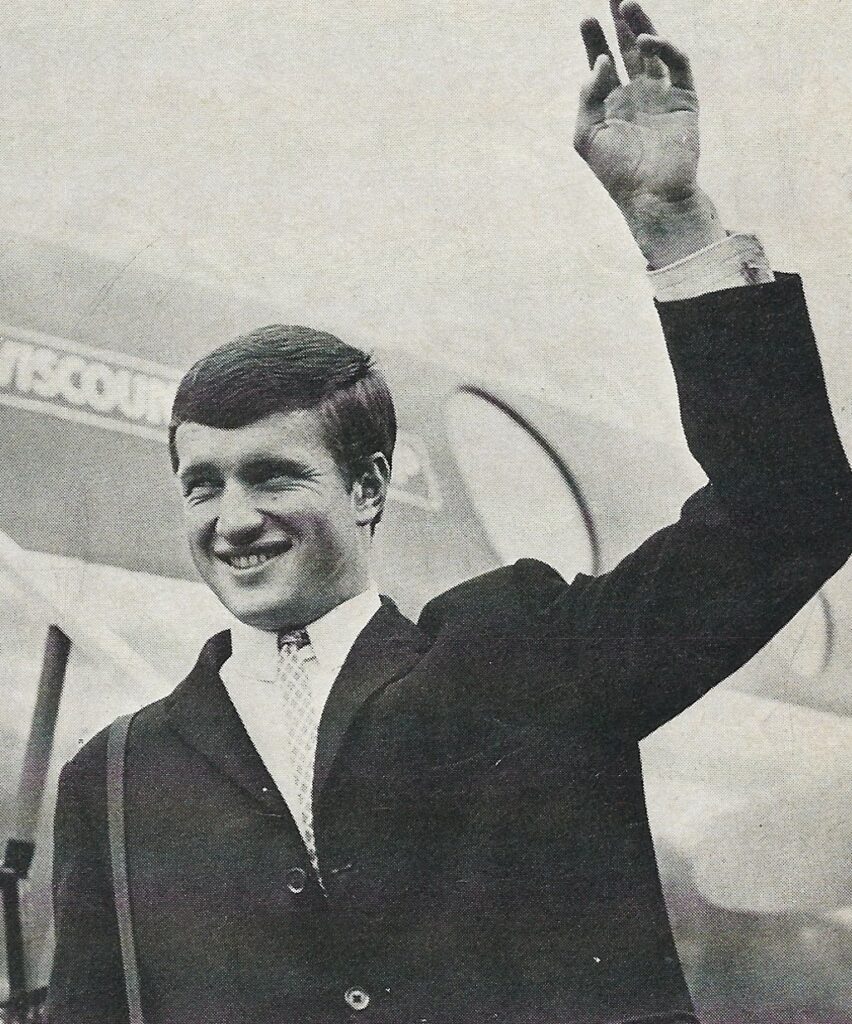

Tommy’s first team debut, after only a handful of reserve appearances, came in a midweek Inter-Cities Fairs Cup match on 14 October 1964. Alex Parker, who had succeeded Roy Vernon as club captain, was unfit to play, so Harry Catterick turned to the 20-year-old rookie (Tommy had travelled with the squad to Norway for the first leg but hadn’t got onto the pitch). 20,717 spectators passed through the Goodison Park turnstiles and saw the debutant play his part in a 4-2 win over Vålerengens. ‘A great debut for young Tom Wright’ proclaimed Leslie Edwards in the Echo. Three days later Tommy made his league debut for the Toffees at Bloomfield Road (the same stadium where Joe Royle would make his first team bow, in more controversial circumstances, 14 months later).

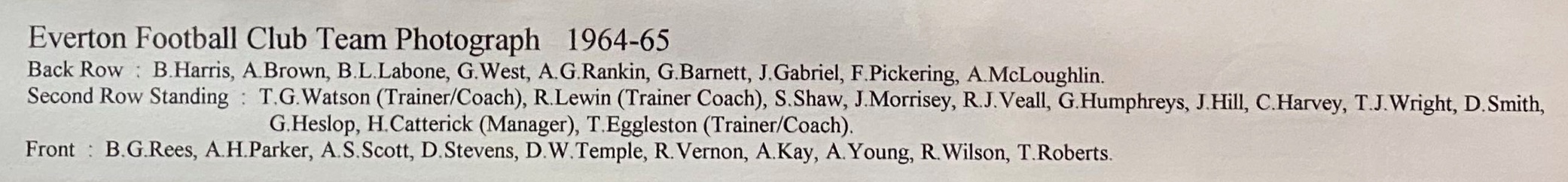

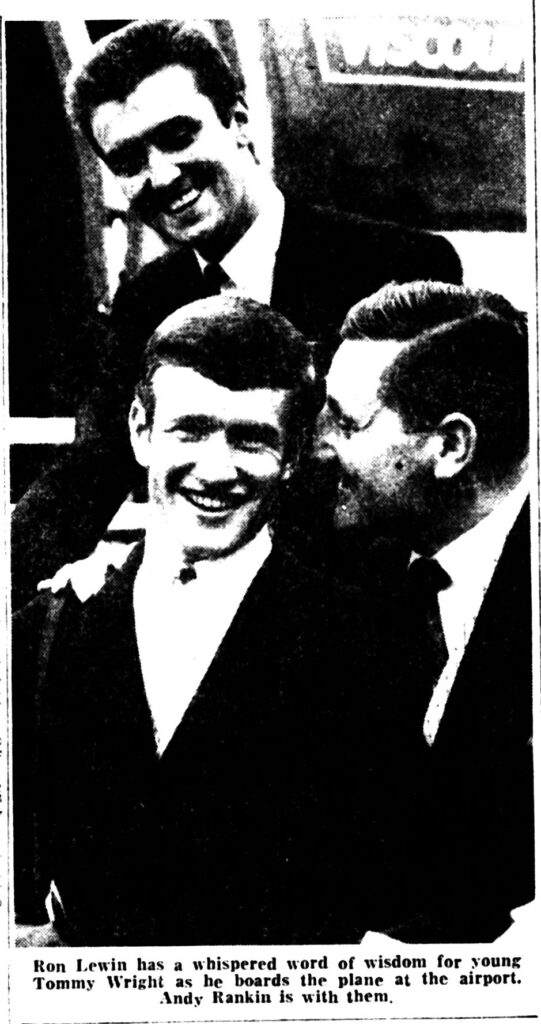

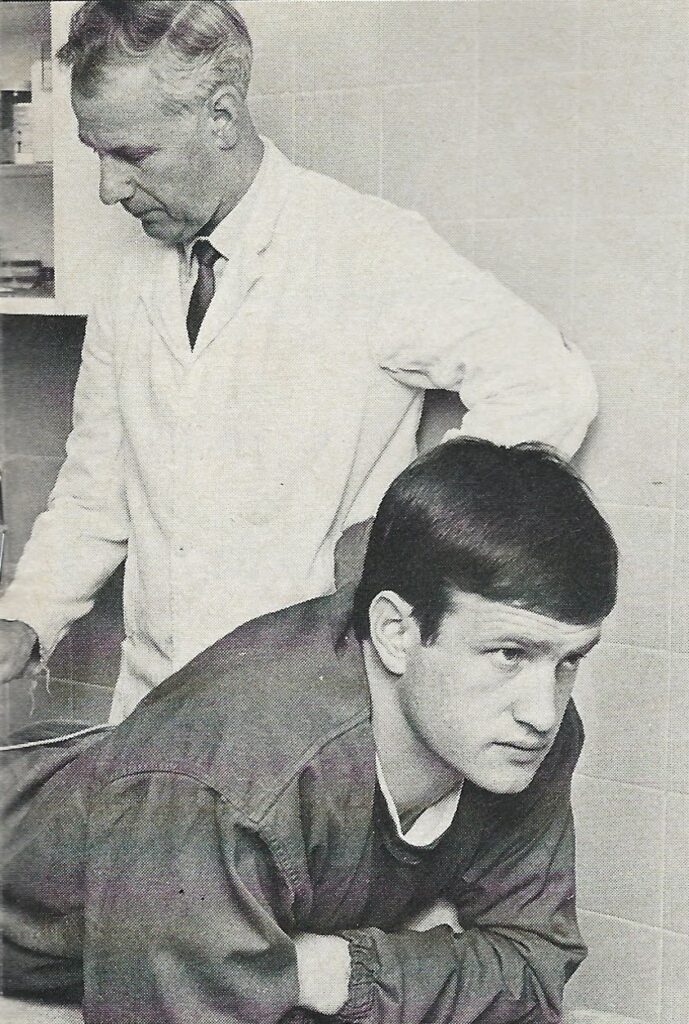

Flying to Norway in September 1964

(Left: Coach Ron Lewin with Tommy before flying to Oslo in September 1964)

In his own words, ‘I didn’t set the world on fire in this game; it was my mistake that gave Blackpool their goal in a 1-1 draw.’ Tommy’s mishit back pass to Andy Rankin did lead to the Seasiders’ equaliser, however, he was being modest about his positive contribution to proceedings. Michael Charters in the Liverpool Football Echo noted: ‘For Everton no one was doing better than Tommy Wright, playing his first League game.’ Commenting on his error for the equaliser, Charters was perceptive: ‘Young Wright need not worry about this, for if Everton have lost a full back in Brown for some weeks, they have found another one in this Liverpool boy. As he gains experience I think that Wright is going to rate a regular first team place. His heading and positional play are particularly good.’

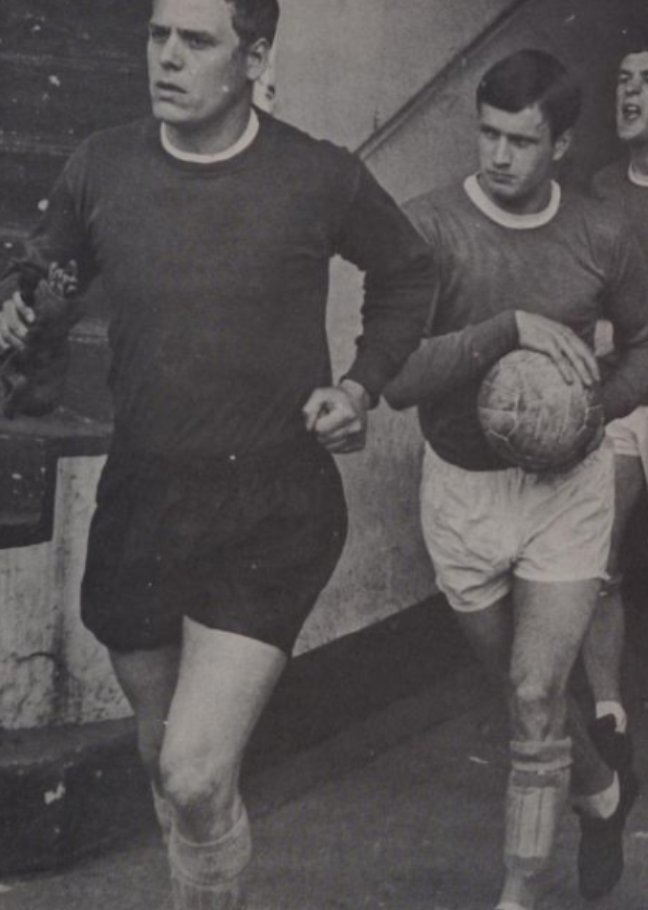

Alex Parker would soon be restored to the team, but when he suffered further injury problems in November, Harry Catterick had little hesitation in blooding his inexperienced right back for the rest of the season, Tommy making 28 appearances, in all. His defensive partnership would be with the immaculate Brian Labone and Ray Wilson and centre and left back, respectively. Their innate assurance doubtless helped the Norris Green lad settle into the first team. Although outwardly confident, the right-back shared the superstitious traits of many sportsmen, in his case he liked to be the third player running onto the pitch third, clutching a football.

Tommy Wright defending, alongside Gordon West and Ray Wilson, with Jimmy Gabriel on the right.

The Leeds player is former Everton star, Bobby Collins.

Congratulating two-goal hero Mike Trebilcock

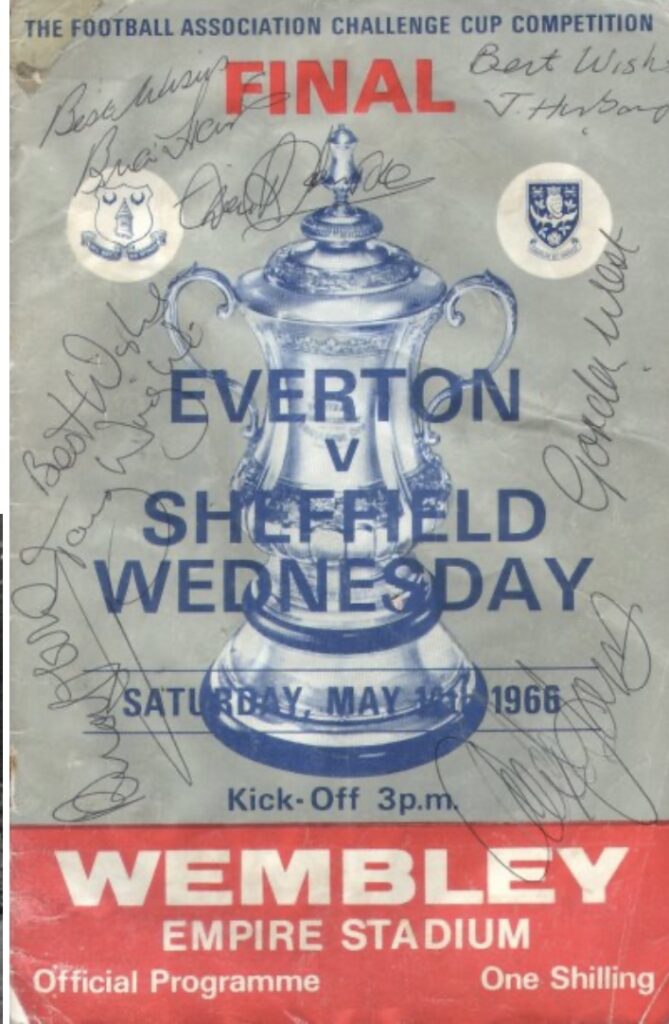

He continued as the regular pick in the number two shirt during the 1965/66 season, but was replaced by the dependable and versatile Sandy Brown for several matches in the weeks leading up to the FA Cup Final. Catterick broke the news on the day before the match that Tommy would get the nod over Brown – this choice by the manager was overshadowed by the decision to bring in the relatively unknown Mike Trebilcock for injury-troubled star striker Fred Pickering. Thus, Tommy would join fellow local lads Brian Labone, Brian Harris and Colin Harvey on the pitch at Wembley. An enduring memory from that epic match is of him shaking off an attack of cramp to sprint back and make an important stop as the Blues held on to a 3-2 lead.

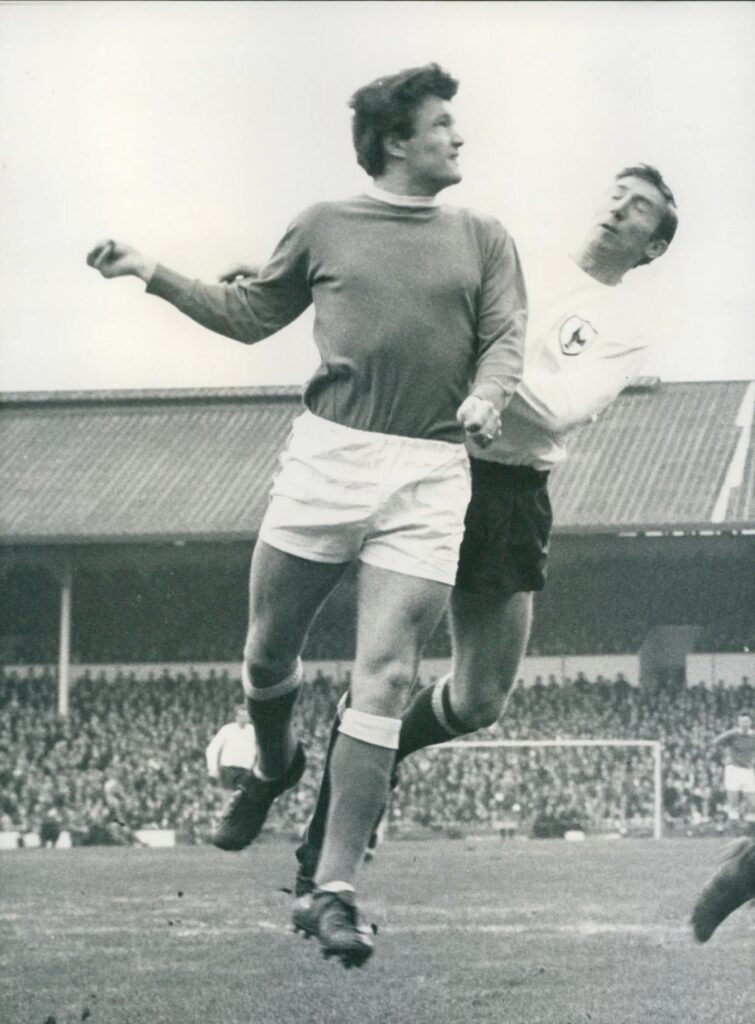

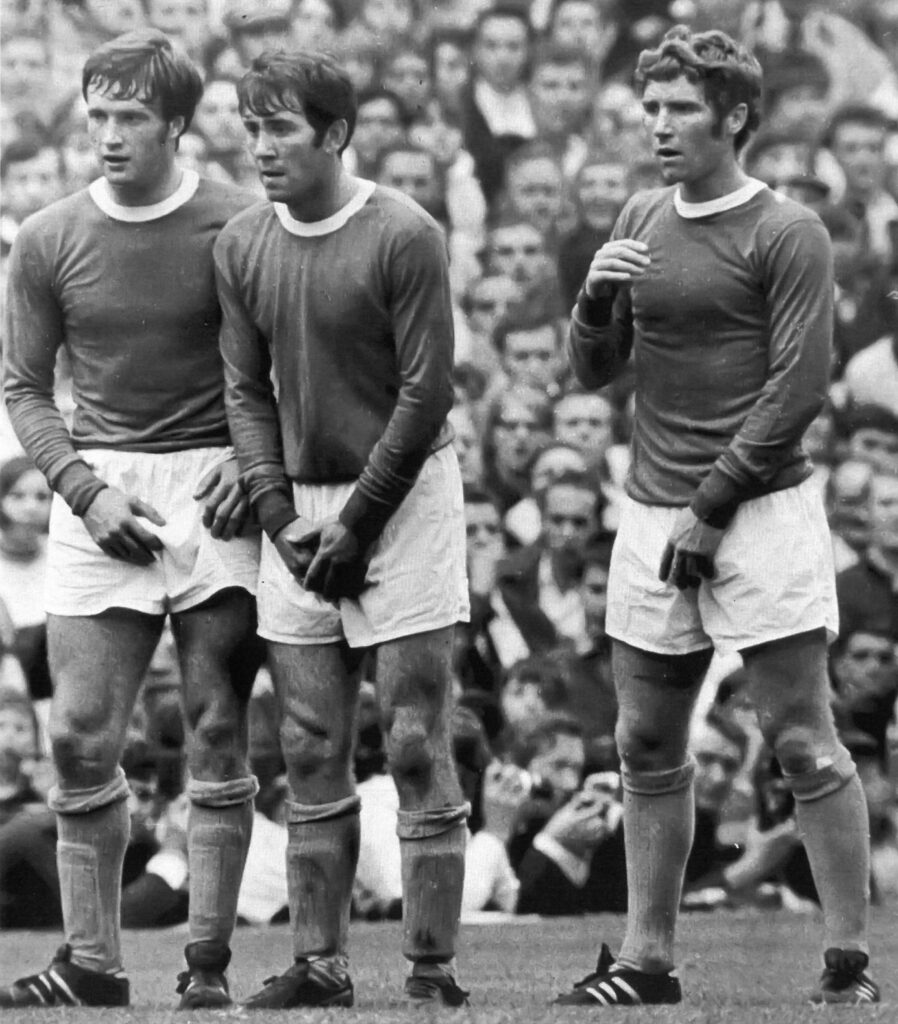

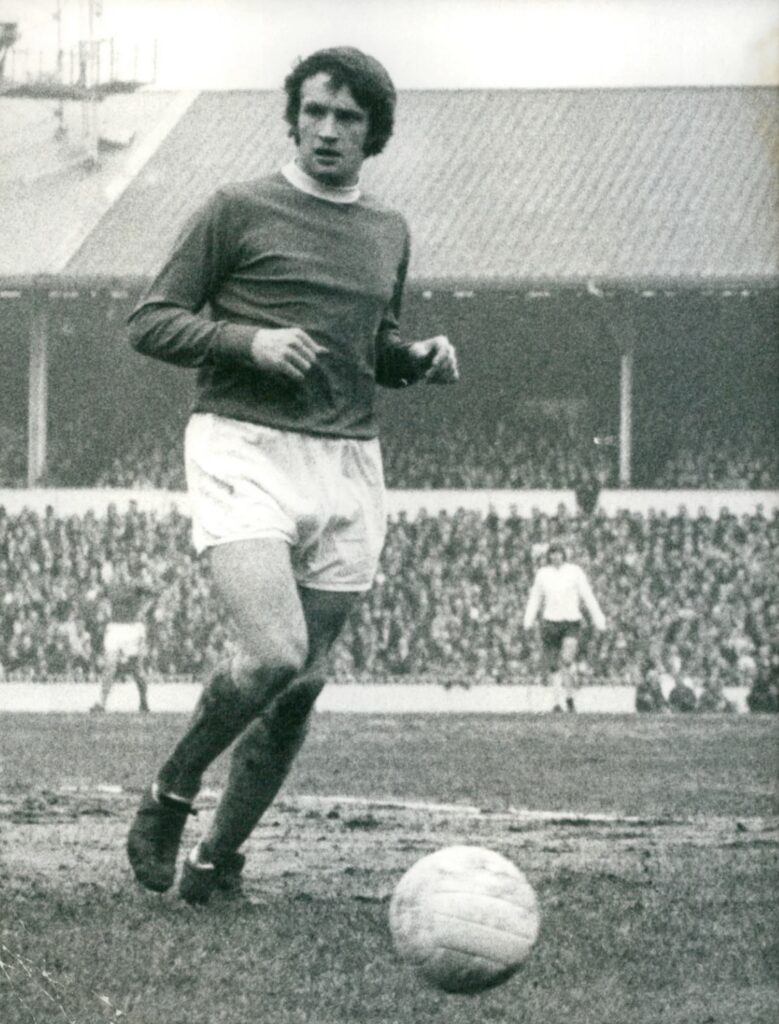

(Showing his excellent leap at White Hart Lane in 1966 and below, Harvey, Ball and Wright in the 1968-69 season)

Tommy never looked back after that heady day in north London. Rarely absent through injury, he was virtually undroppable. In the five seasons from 1966/67 onwards he made 53, 46, 50, 47 and 53 appearances in all competitions. He was an ever-present in the glorious title winning campaign at the end of the decade and had, by this point, built a fine understanding with Howard Kendall on the right side of midfield, with Jimmy Husband roaming ahead of them, with some magnificent interchanging, dragging opponents out of position. He had benefitted from the rapid evolution in formations in the mid-1960s and had license to deploy his youthful attacking experience by bombing forward and overlapping. His 200th league appearance came in the December 1969 Merseyside derby (a rare blip in a spectacular season for that pure footballing side). That same week, Harry Catterick, not famous for dishing out praise, gave a rare TV interview in which he ran through the Everton side. Of his right-back, he said: He has great ability to look for space up front. This may have come from his days as a forward. He has great recovery powers.’

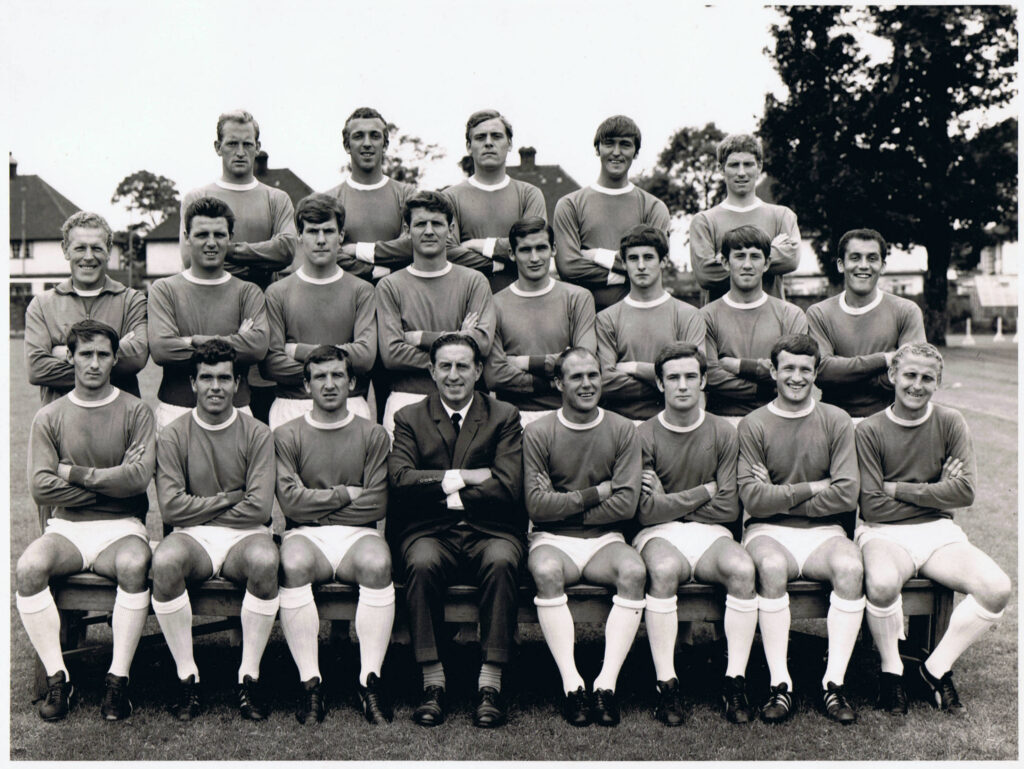

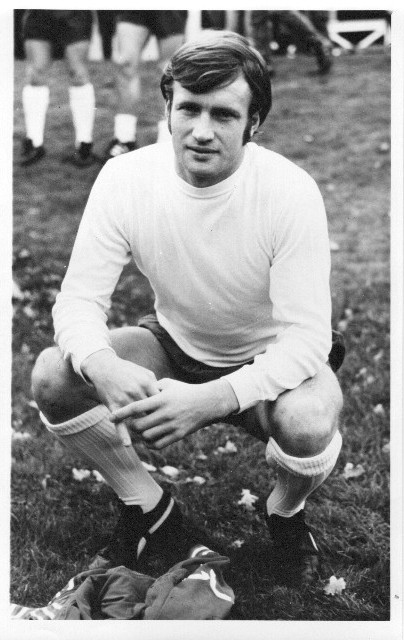

At Bellefield in July 1968

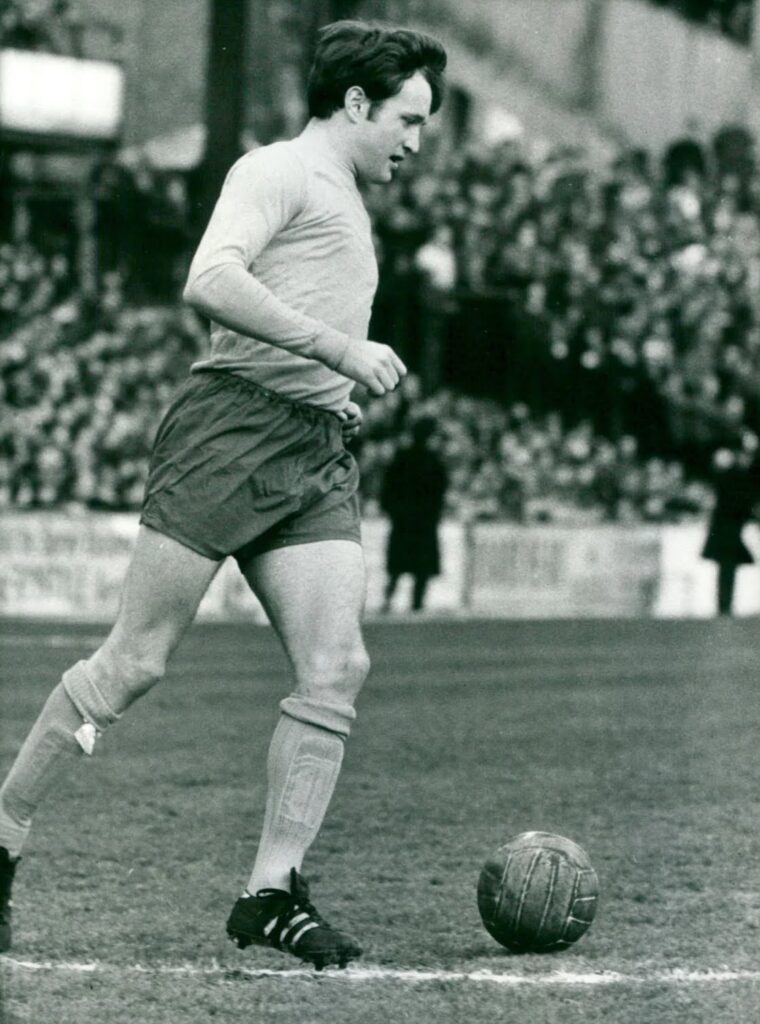

(Above) Defending against Jon Sammells of Arsenal and Cutting a dash in amber in 1970.

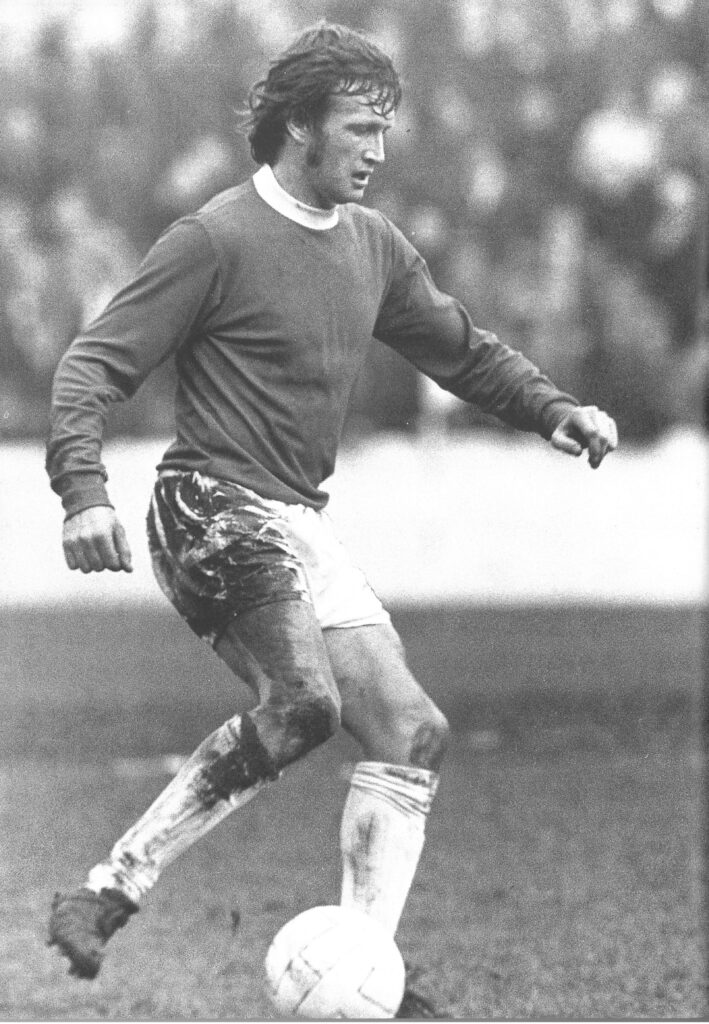

(Above:) On the ball in the away kit and Muddied but unbowed in the early 1970s.

On the international front, consistency and excellence for Everton saw Tommy rewarded with a first England Under 23 cap in December 1967. In May 1968, he had the pleasure of wearing the three lions shirt for the Under 23s at Goodison Park, a comfortable 4-0 defeat of Hungary. Six weeks later came the ultimate honour of a senior team debut in Rome’s Olympic Stadium, after being promoted from a tour with the Under 23s. It was made all the more satisfying by lining up in the defensive unit which also included clubmates Ray Wilson and Brian Labone (with Alan Ball on the bench). They kept a clean sheet in a 2-0 victory over Russia, which confirmed a third-place finish for England in the European Championships.

In the late 1960s, Tommy would battle Keith Newton for the number two shirt in the England side. There was some irony when Newton transferred from Blackburn Rovers to Everton in December 1969, tasked with playing at left-back! Although now clubmates, the pair would continue their rivalry for the right-back spot in the national team – all the way to the World Cup Finals in Mexico. Newton was Alf Ramsey’s first choice when the tournament got underway, but an injury to the Mancunian at the hands of Romania, saw Tommy get his chance as a substitute.

(Tommy is crouched between the two goalscorers)

The UEFA/FIGC II Campeonato d’Europa per Nazioni Coppa Henri Delaunay Finals Third-Place match

Stadio Olimpico, Municipio XV, Roma, Italy, Saturday, 8 June 1968

Attendance:68,817 (Chris Goodwin http://www.englandfootballonline.com )

Tommy front centre, with Everton colleagues Gordon West, Brian Labone, Alan Ball

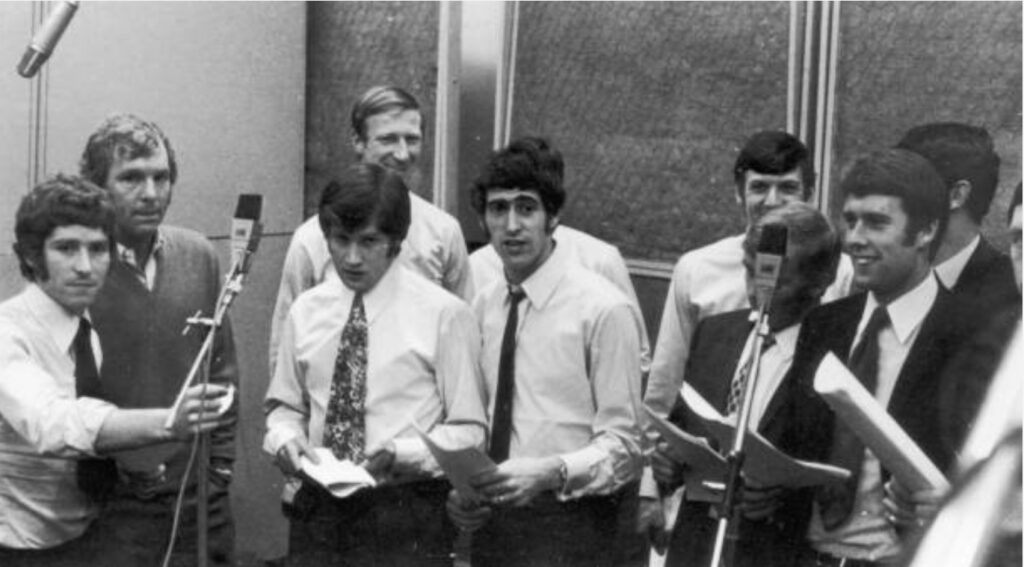

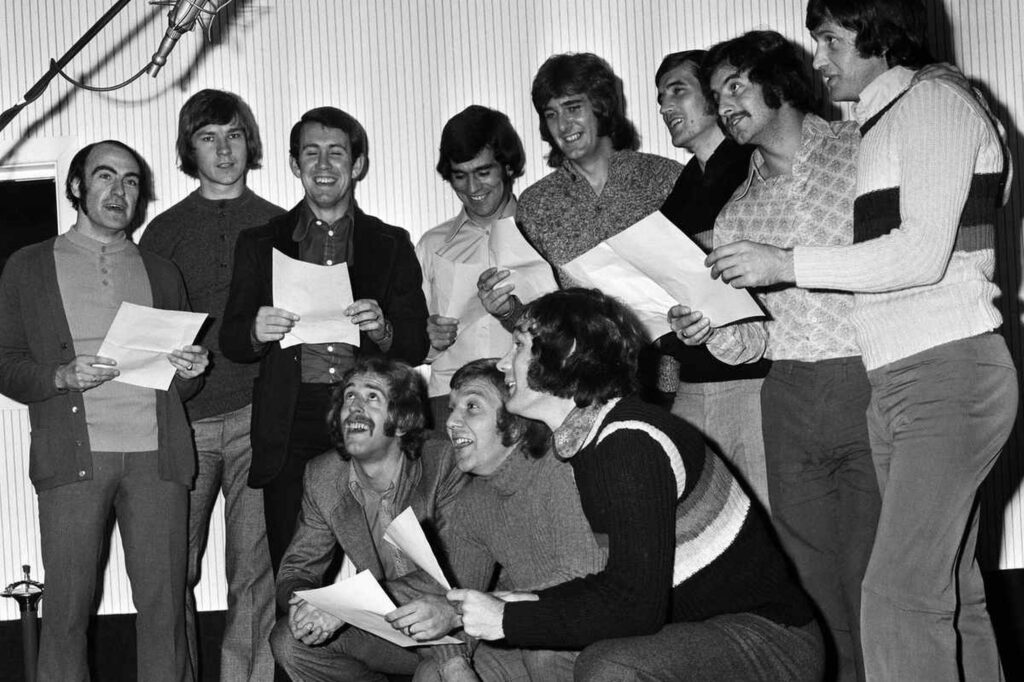

Part of the England soccer team record the World Cup song ‘Back Home’ at the Pye recording studio in London.

From left to right, they are Alan Ball, Bobby Moore, Tommy Wright, Jackie Charlton, Peter Bonetti, Martin Peters, Francis Lee and Geoff Hurst. 22 February 1970.

With Newton still recovering, Ramsey turned to Tommy for the group match against Brazil five days later. The manager broke the news to the defender the day before the big match. Such was the noise generated by Mexicans and Brazilians outside the England team hotel that night, that Tommy was forced to join Alan Mullery and Bobby Moore in the room they shared at the rear of the building. Before kick-off, the manager had a quiet word with his right-back, telling him to just play his normal game, stay close to the right flank and pick up the nearest man (Mullery had instructions to man-mark Pelé).

Tommy Wright of England (left) deftly evades a lunging tackle by Paulo Cesar Lima (Caju) of Brazil during the 1970 FIFA World Cup group 3 match between Brazil and England at the Jalisco Stadium in Guadalajara, 7th June 1970. Brazil won 1-0. (Photo by Paul Popper)

The Everton man gave a marvellous display, outpacing winger Paulo César early on to get in a clearance and subsequently getting to the line and putting over a peach of a cross from which Francis Lee tested the Brazil goalkeeper with a header. In the eyes of a number of reporters and his teammate Alan Ball, Tommy was the best player on the pitch that day. In the end, in searing heat, England fell to a 1-0 defeat thanks to a Jairzinho goal. The players were weighed before and after the match, most being found to have sweated off six or seven pounds (three kilos). Despite his heroics in Guadalajara, Tommy reluctantly then ceded his place to the fit-again Keith Newton and would not add to his tally of 11 caps (he was called up for a squad for a match in the November 1970 but had to withdraw through injury).

After another arduous season, which saw Everton knocked out of the FA Cup at the semi-final stage, and the European Cup at the quarter-final stage, the miles on the high mileage on Tommy’s body began to manifest itself in injuries – just as they did with Brian Labone, John Morrissey, Jimmy Husband and others. Tommy’s woes began with a knee injury sustained on the opening day of the 1971/72 season, which led to him missing nearly three months of action. This was followed by an ankle issue – so, he only managed a relatively meagre 18 appearances.

Tommy in the iconic amber and blue away kit in 1968 (left) and in the added EFC monogram shirt in 1972 (right).

In a struggling side, he was able to make 32 starts in the 1972/73 campaign but missed some matches in the autumn with strained stomach muscles. As the Harry Catterick era drew to a close in April 1973, so did Tommy’s playing career. In just the second match after the news of the long-serving manager stepping aside was made public, Tommy sustained a further injury to his left knee and was substituted on seven minutes against Wolves, to be replaced by Terry Darracott. No-one, least of all Tommy, would have known it, that at just twenty-eight he had pulled on the royal blue shirt for the final time.

After some rest over the summer of 1973, it was hoped that the knee ligaments had healed without the need for surgical intervention. However, a pre-season training session on the sands at Ainsdale, under the watchful eye of new manager Billy Bingham, saw him break down again. It started when Tommy attempted to latch onto a slightly wayward pass from John Connolly in a small-sided game on the beach: ‘I stretched for the ball and my left knee just collapsed under me,’ he recalled. One wag in the squad, not appreciating the severity of the injury, drily commented that Tommy would do anything to avoid having to do the gruelling runs up the sand dunes.

The wrench to his knee had displaced a cartilage, so he went under the knife in early August, before embarking on the long and solitary road to recovery, in the care of club physio Norman Borrowdale. Tommy explained that it was quickly apparent that the knee was in worse shape than had been appreciated: ‘I still had no inkling that there were any problems other than restoring full movement and muscle wastage to the joint, but I found out differently once I started joining in five-a-side practice matches. As soon as I put the least bit of pressure on the knee, by turning or attempting to do something quickly, there would be an immediate onset of fluid around the joint and eventually this was diagnosed as ligament trouble. So really, with the cartilage operation a real success, I found myself back once again deep in the problem that beset me last season.’

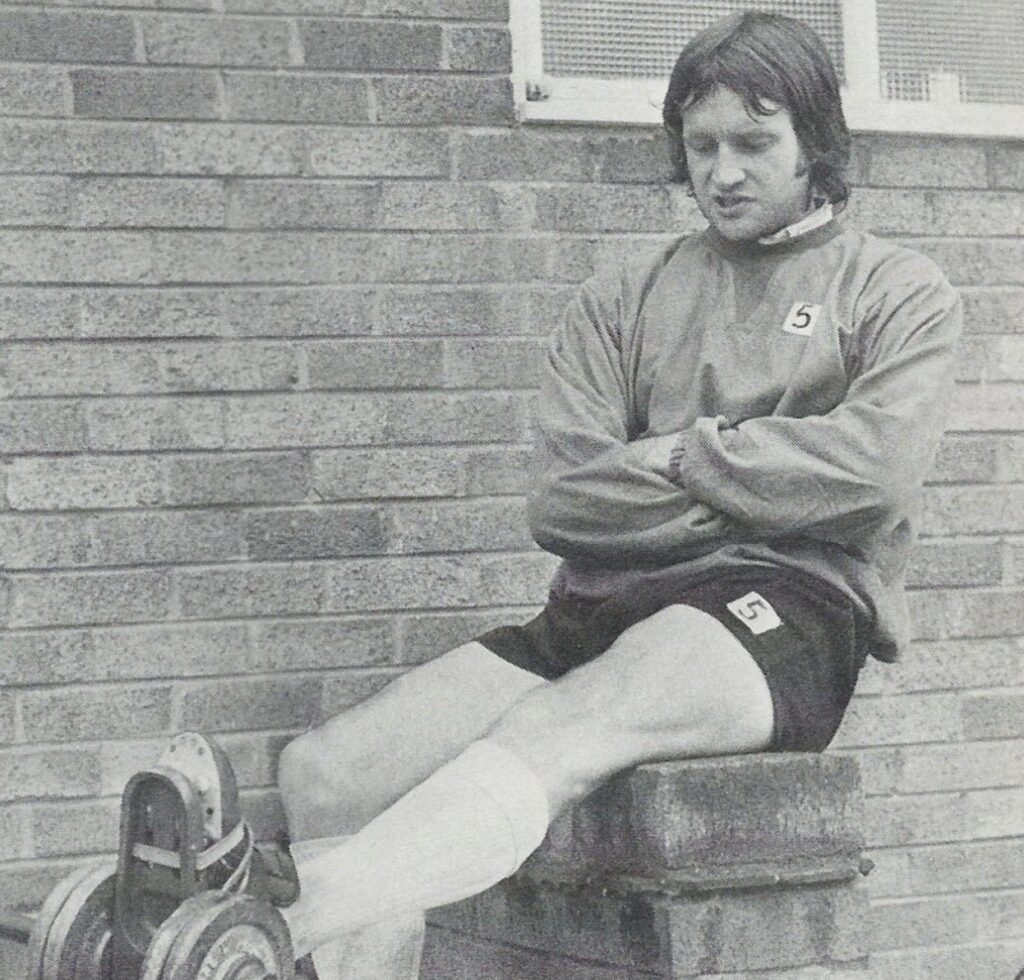

Tommy battled hard to recover, but the desperately poor condition of his left knee ligaments meant that he could not kick the ball in anger or have any meaningful physical contact with clubmates, although Billy Bingham did integrate him with the first team squad, where possible. His regime consisted of doing circuits and weights, in an attempt to strengthen the quads and compensate for the knee’s weakness. It was tough going, as he confessed to the club’s matchday programme in the autumn of 1973:

‘This can be something of a soul-destroying activity – especially if, as I am, you are having to do it alone. You sit there raising and lowering your legs with weights attached to your foot and spend hours just counting the number of times you do exactly the same thing.

‘Your schedule might be three sets of 30 lifts or three sets of 40 according to the weight that’s attached to your foot. And you do this six days a week – week in, week out. If you’re not doing this then you are doing step-ups on a bench with the left leg taking all the strain and weight of your body. Again, all you can do is count out the required number.

‘It is a tremendously monotonous exercise and when, once you feel fit enough to resume more active training, the injury flares up again. It can be most disheartening because you begin to despair where it all is going to end.’

Dave Clements, who had replaced the recently-departed Howard Kendall as Everton captain, reflected on how tough the ultimately doomed quest for a return to something close to full fitness was: ‘I’ve seen him struggling in training. You could see him in real pain at times from his damaged knee, but he just gritted his teeth and got on with it.’

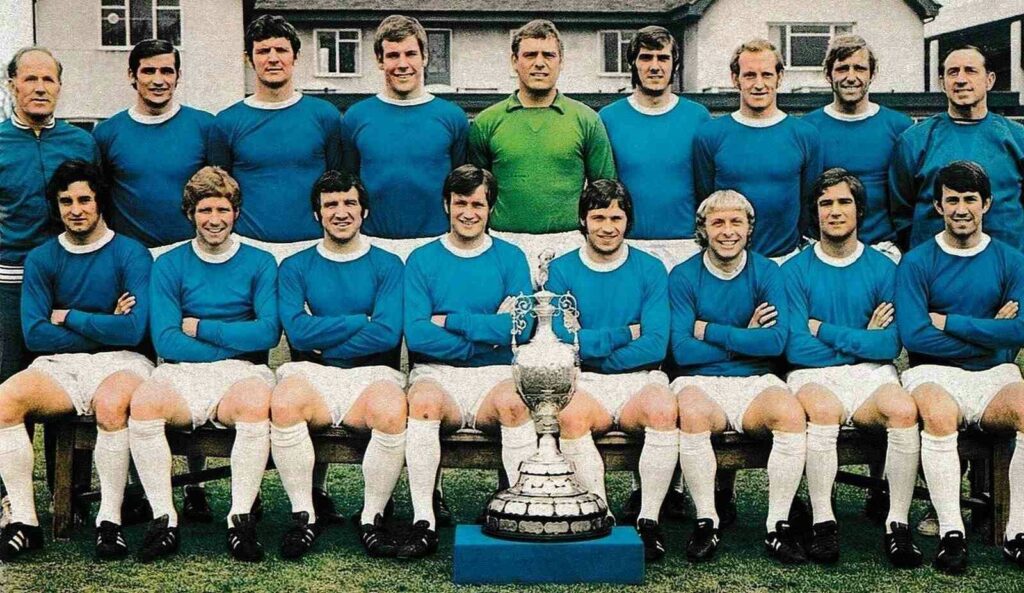

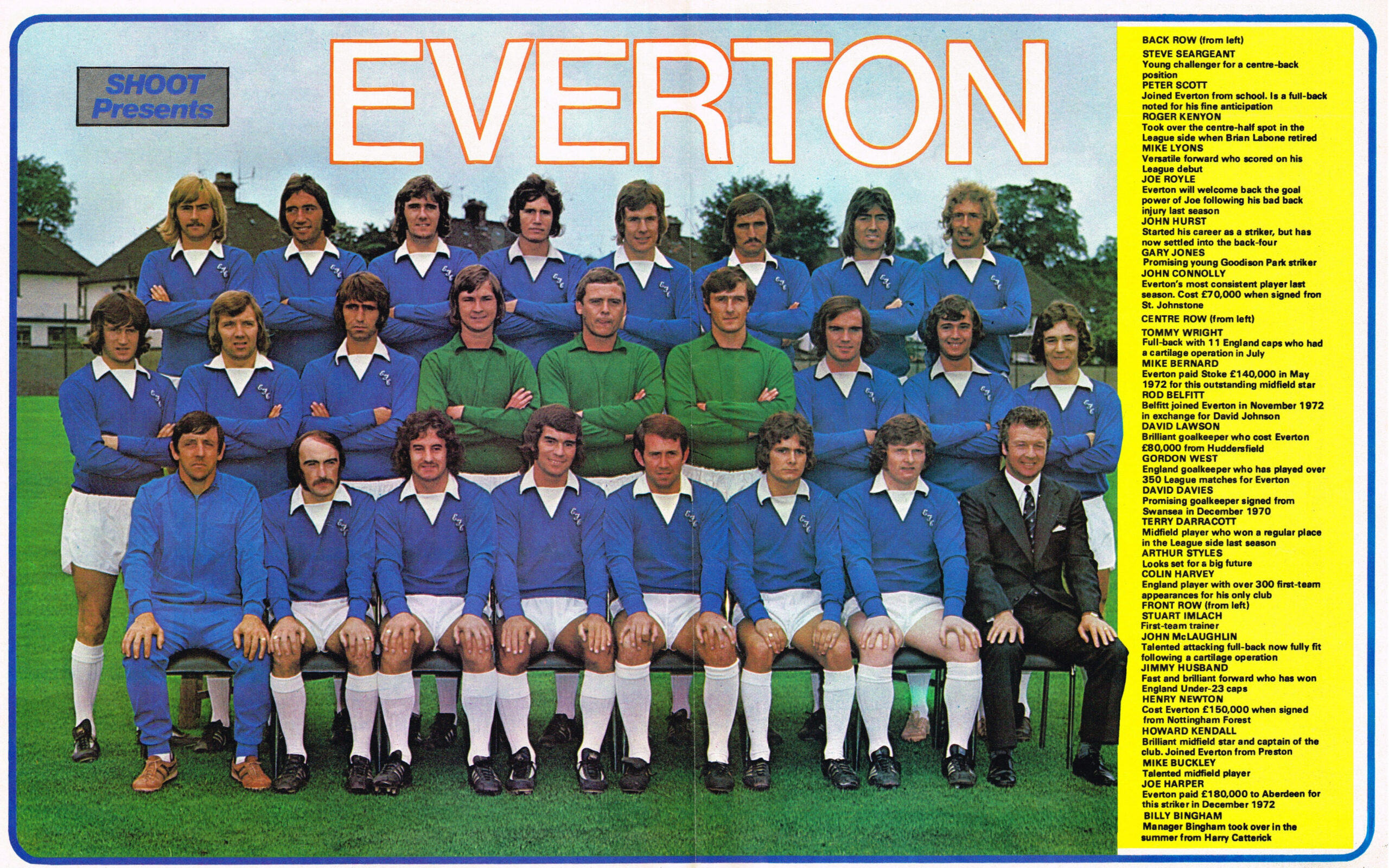

which would prove to be Tommy’s final team photo call

Tommy’s fate was confirmed by a visit to a specialist, who advised that further attempts to play football would lead to irrevocable damage to his knee, leading to permanent debilitation. The news broke at the end of February 1974 that Tommy would be retiring from football after making 374 senior Everton appearances (22nd in the club standings, as at January 2026) and 11 international appearances. He could rightly be compared to the Toffees’ greats who had occupied the right-back berth like his predecessor Alex Parker, Billy Cook, Warney Cresswell, Ben Williams and Bill Balmer.

It can be argued that in the wake of Tommy’s retirement, the Toffees did not field a top-class right-back – with the possible exception of John Gidman – until the emergence of Gary Stevens, nearly a decade later. In the short term, Peter Scott and Terry Darracott had the daunting task of filling Tommy’s boots. The latter reflected in the 1980s on the high bar set by his predecessor.

‘I would say he [Tommy] was the finest right-back I have seen at Everton. He went right to the top of the tree, winning FA Cup and league championship medals along the way. He was very quick, with a good right foot and did not give the ball away very often. First and foremost, he was a good defender who was not easily beaten and was very difficult for wingers to play against. They would often not get a kick. He would break up attacks and, unlike some defenders, his touch was good on the ball. He was also good at going forward and overlapping and he could get in a decent cross. Because of his earlier career, he knew what he was doing when he ventured up the park. Although he was not a man of many words and was generally very quiet, he was certainly an inspiration to me as a young lad, and I was encouraged by the way he used to work at the training ground.’

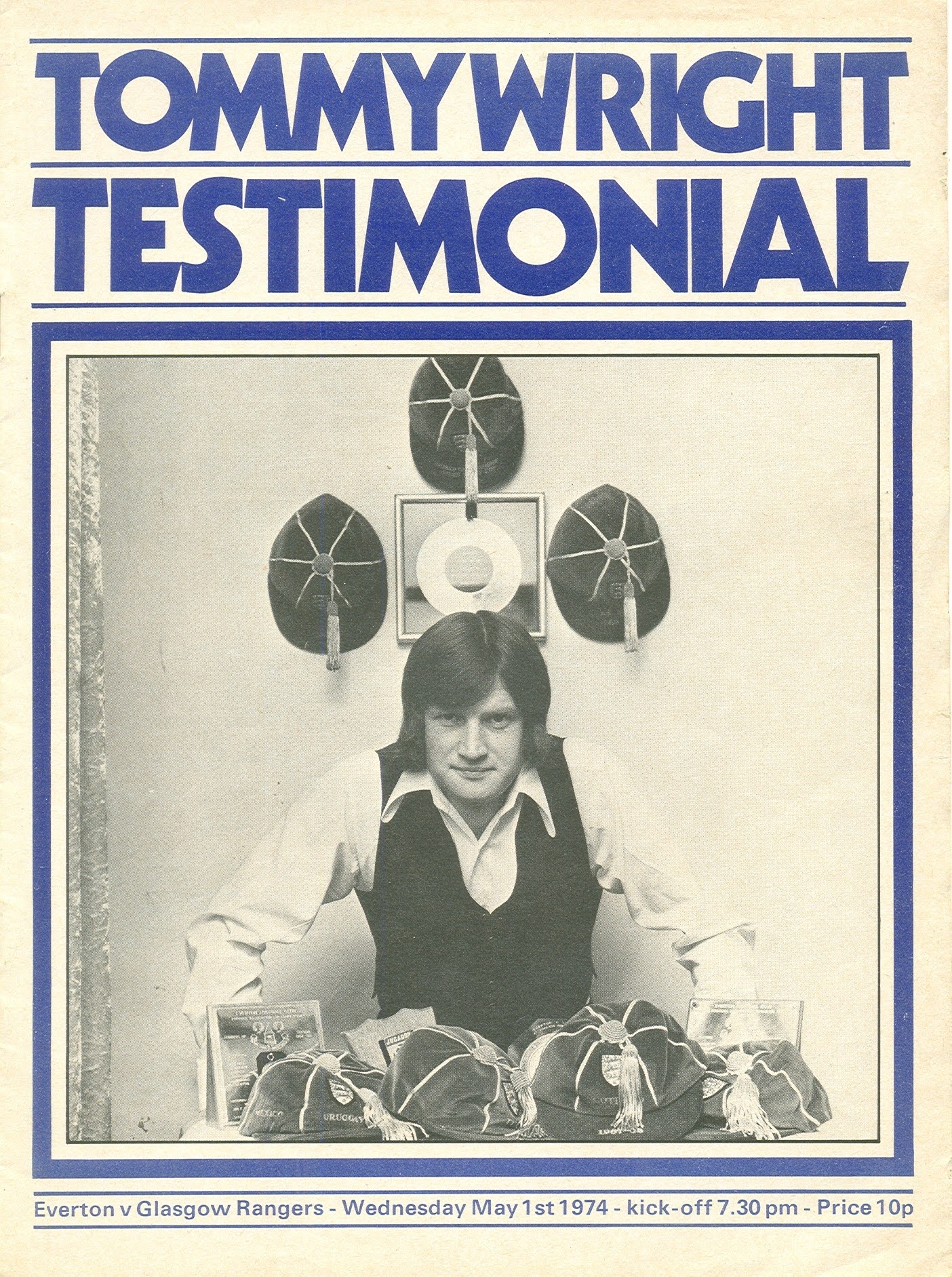

In the wake of the news of Tommy’s retirement from football, a testimonial match was arranged, to be played against Rangers at Goodison Park in May 1974. The match programme included tributes from Brian Labone, Gordon West and former England teammate Bobby Charlton. Tommy used the publication to thank everyone connected to the club for his playing career.

What can I say other than thank you to everyone concerned for tonight’s testimonial match for me. Naturally, I am deeply upset that I cannot play a further part in the future of Everton Football Club, or any other club, for that matter.

But I must go on record as saying how fantastic it has been for me to have been a part of such a wonderful club. I have sampled the triumphs and tasted the disappointments – but the happy times far outnumber the sad ones. It is a sad goodbye that I have to make, tonight, but at the same time I feel honoured that so many have felt enough to make the effort to show their appreciation for the contribution I have always tried to make to Everton and the game in general.’

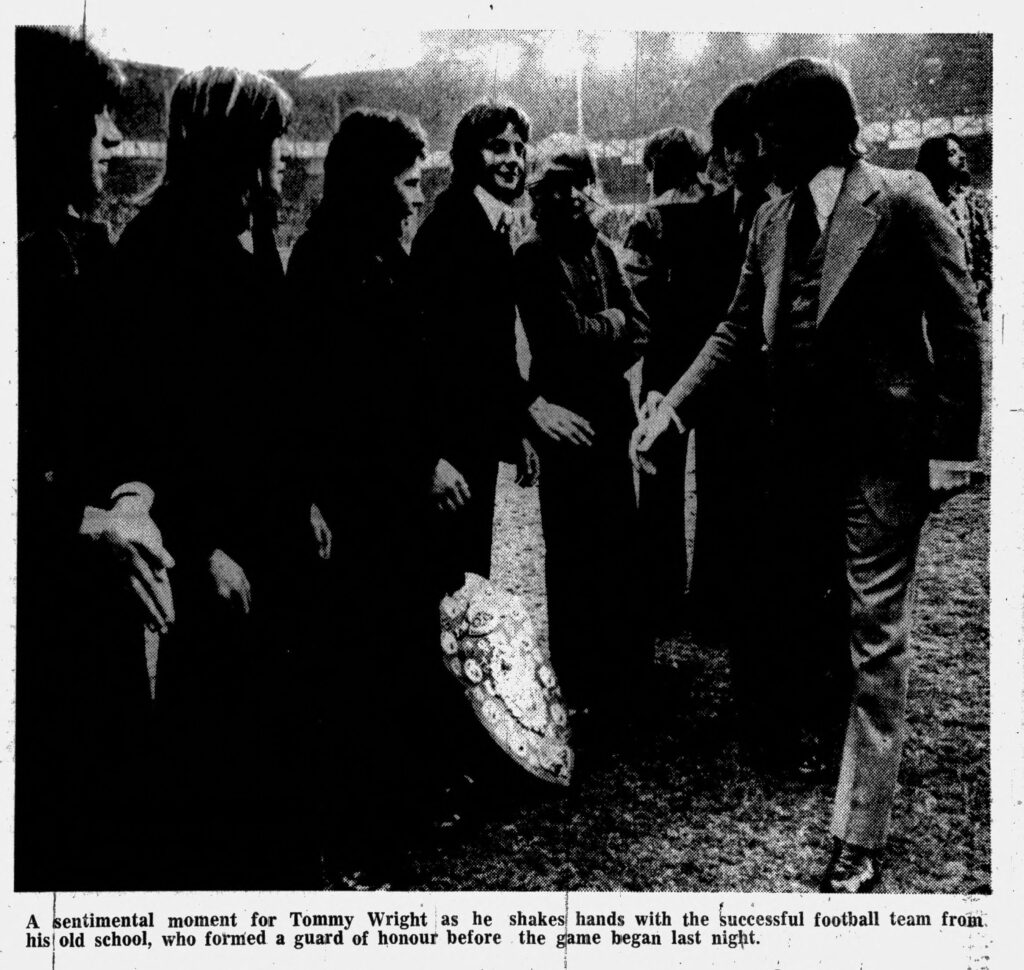

Before kick-off, Tommy was given a warm ovation, with pupils from his old secondary school providing a guard of honour. The match, a 2-1 win for the hosts, was marred by torrential rain, which may have been a factor in the attendance figure only just topping the 10,000 mark. Aside from the Bob Latchford and Mick Buckley goals, the game was remembered for the first appearance of a streaker on the Goodison Park pitch.

With the testimonial match and several other fundraising events concluded, Tommy had to face up to the reality of a life beyond football; he had no plans to remain within the game as a coach or manager. He was quoted saying: ‘Now I must look ahead to the future. I don’t really know what I am going to do because I came into football straight from school and I do not have any business interests. As far as a job goes, I am just going to wait and see. But after all these years in football, I do not really fancy an office job of any sort with “9 to 5” hours.’

Of course, it was a case of ‘needs must’, which must have been difficult to adjust to. Tommy would initially be offered employment by the Littlewoods organisation, just as he had been in the early 1960s, before setting up a security firm with his brother. In the early 1980s he working at Barker and Dobson’s sweet factory (at that time, they were the suppliers of Everton Mints for the Toffee Lady matchday mascot), eventually working on the docks in Garston, something he appreciated for being outdoors, just as he had been as a footballer.

After hanging up his boots at Bellefield for the final time, he did not turn his back on football, altogether. A regular attendee at Goodison Park matches for many years, Tommy accepted an invitation to be trainer (possibly playing, on occasion) for Tithebarn FC of Cantril Farm in the fourth division of the Liverpool Sunday League for the 1976/77 season. In the early 1980s he was turning out in midfield for Garston Woodcutters FC. He also graced Goodison Park again on a couple of occasions – notably in Mike Lyons’ testimonial match in 1980. When the club laid on a reception at the Littlewoods head Office in 1978 to mark its centenary, Tommy was named as one of the VIP guests alongside stars of yesteryear like Ted Sagar, Joe Mercer, Peter Farrell and Bobby Collins.

In 1996, budding sports journalist James Corbett, now a successful author and member of Everton FC Heritage Society, was able to get an audience with Tommy for his Gwladys Sings The Blues fanzine. James remembers being taken from the docks to Tommy’s nearby house by a work colleague of the former England star. He was struck by how modest (but beautifully maintained) the one-time Goodison Park hero’s home was. James recalled:

‘Tommy still possessed the wiry frame of an athlete, and although now in middle age his craggy, weather worn face remained recognisable from photographs of him in his 1960s pomp. But he was a humble man and there was no swagger, no sign that he was the man whom George Best once said was his most difficult opponent and who the famous Italian football agent, Gigi Peronace, described as ‘Il Magnifico’.’

Tommy wasn’t the easiest interviewee for the teenage scribe. This was not through him being uncooperative (far from it), but down to this most grounded of men being reluctant to blow his own trumpet about a highly-decorated football career. Tommy was far more expansive and effusive when chatting about his Toffees teammates, ‘It’s a dream come true when you’ve always supported Everton and always wanted to play for them. That was always my one ambition in life, to play for Everton. The likes of Alan Ball, Alex Young and the rest took the pressure off if you got the ball. All you did was give it to them and let them do all the work. My job was to get the ball off the other side and give it to them.’

James recalled that the conversation drifted away from Tommy’s career, ‘Like most working-class men in the city, he knew his football like he did his family and was able to see subtleties and nuances in the game that escaped my eyes. So, rather than talking about his life and times we chatted for the rest of our time together about the game in general, and Everton in particular, who he still loved and watched every week.’

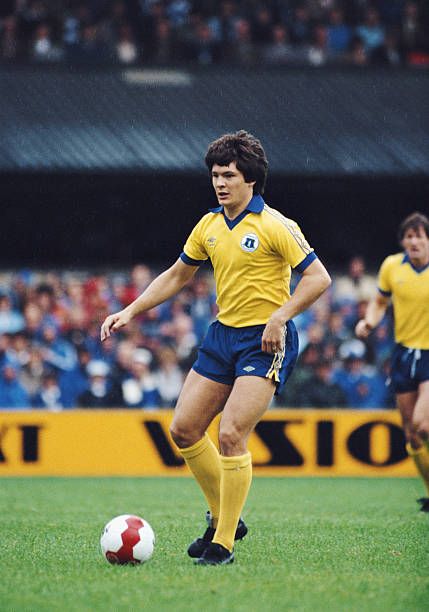

Tommy would have been justifiably proud to see his nephew, Billy Wright, come through the ranks at Everton in the 1970s, briefly captaining the side in 1982. Billy had grown up watching his uncle turn out for his beloved Blues, by 1982 it was Tommy offering his nephew a few quiet words of encouragement as he prepared to lead the side onto the pitch. Meanwhile, Tommy’s niece Emma Wright (now Emma Wright Cates) represented Everton Ladies when they won the Women’ s Premier League title in 1997/98.

represented Everton Ladies when they won the Women’ s Premier League title in 1997/98 (click for special feature)

When David France pioneered the Gwladys Street Hall of Fame nights in the late 1990s/early 2000s, Tommy was reunited with his former colleagues, plus many adoring fans, one of whom was Mike Royden (now vice-chair of Everton FC Heritage Society), who recalls:

‘I was tasked with looking after some of the players in the private lounge before the main event started. This included arranging photographs and group shots to record the occasion. Needless to say, I soon took advantage of my fortunate situation and asked the photographer to take a few for my collection. Imagine how overawed I was finding myself standing between two of my all time heroes, Alex Young and Tommy Wright. It was like I was ten years old again. I had a chat with Tommy, but with me being star struck, and he being his quiet humble self, it was never going to be an in-depth conversation. Nevertheless, he signed my 1966 FA Cup programme, which for me it was an unforgettable moment, now twenty-six years ago, and one I’ll always cherish. Those Hall of Fame nights were always bonkers events. I think Tommy was overwhelmed by the whole occasion, in face of the absolute adoration from grown men, most of whom had grown up with those fabulous sixties sides, collecting their bubblegum cards, sending off tokens off the Typhoo-Tea packets for a treasured photo of Everton, while searching everywhere to find the amber away kit in Subbuteo. Such a brilliant footballer and loyal servant of the club, Tommy Wright will always be an integral part of that childhood memory.’

Tommy Jackson, Colin Harvey and Tommy Wright

(plus Colin Harvey, Brian Harris, Derek Temple, Alex Young, Gordon West,

and Jimmy Husband (although he didn’t play in the game)

Everton supporter Frank Thomas also shared a lovely story of a chance encounter with one of his favourite former players: ‘I was sitting waiting for friends in the Kingsman Pub on Aigburth Road, a few years ago, now. As is my wont, I was reading a book to pass the time. That day my book of choice was Colin Harvey’s Everton Secrets, when a voice behind me enquired: “Do I get a mention in there then?” It was Tommy, the man himself. A nice chat, a beer and I was almost sorry when my friends turned up! He was a gentleman.’

Like many former footballers, Tommy lived with the lasting physical effects of a long, arduous playing career. He had his first knee replacement (on the troublesome left one) in 2006, followed by having his left hip and right knee replaced eight years later. He was quoted after the 2014 surgeries as saying: ‘I’m thrilled with the outcome, up to now. I know I still have some way to go but [surgeon] Mr. Santini has just been amazing, I can’t thank him enough for his support. I’m looking forward to getting out and about a bit more now and I’d just like to say a big thank you to everyone.’

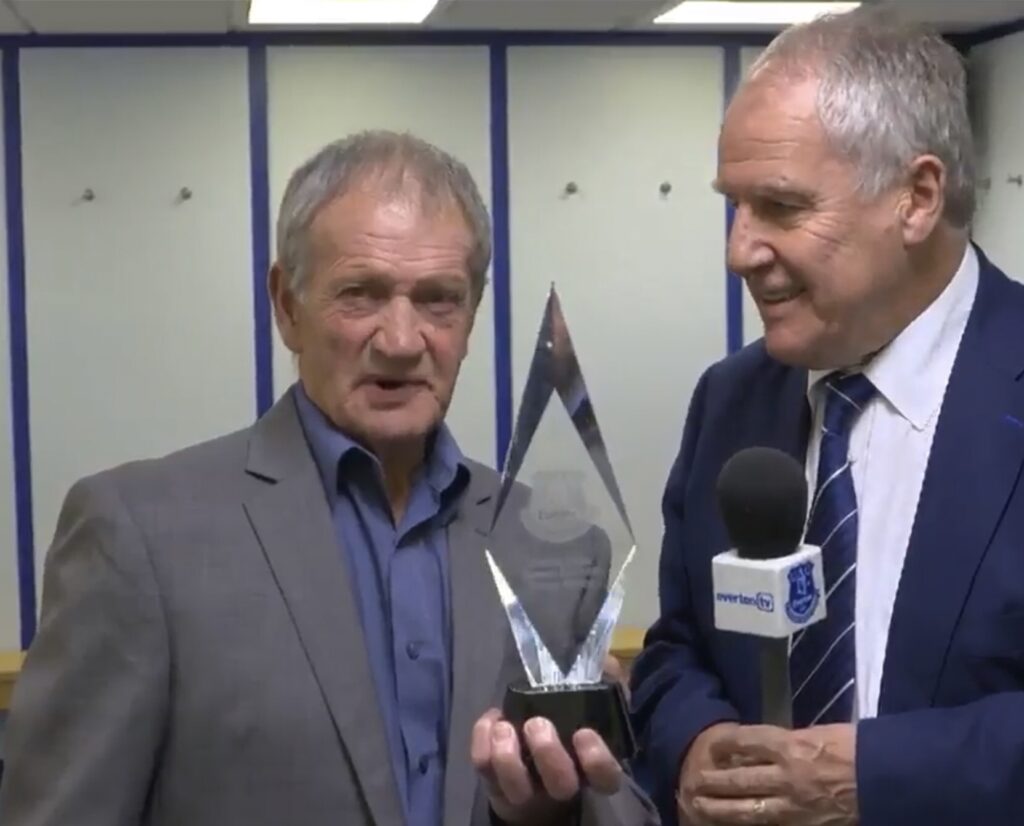

Tommy, who got married to Edna after a divorce from Gwen, suffered his fair share of tragedy, including the untimely loss of his son, Andrew approximately 25 years ago. Possibly connected to this, he was seen less often in Everton circles in the 2010s. A rare public appearance was to deservedly receive Everton Giant status in 2016. Fittingingly, his fellow School of Science graduate Joe Royle was on hand to present the award at Goodison Park and Tommy, bashful as ever, was introduced onto the Goodison Park pitch. On Everton TV, Royle would describe Tommy as the best there was in that era, for club and country. Tommy’s reply was beautifully succinct: ‘The award makes me very proud to be an Evertonian. Thank you.’ In the wake of Tommy’s passing I asked Joe, who was still clearly upset by the loss of his friend and teammate, to reflect on the player and the man:

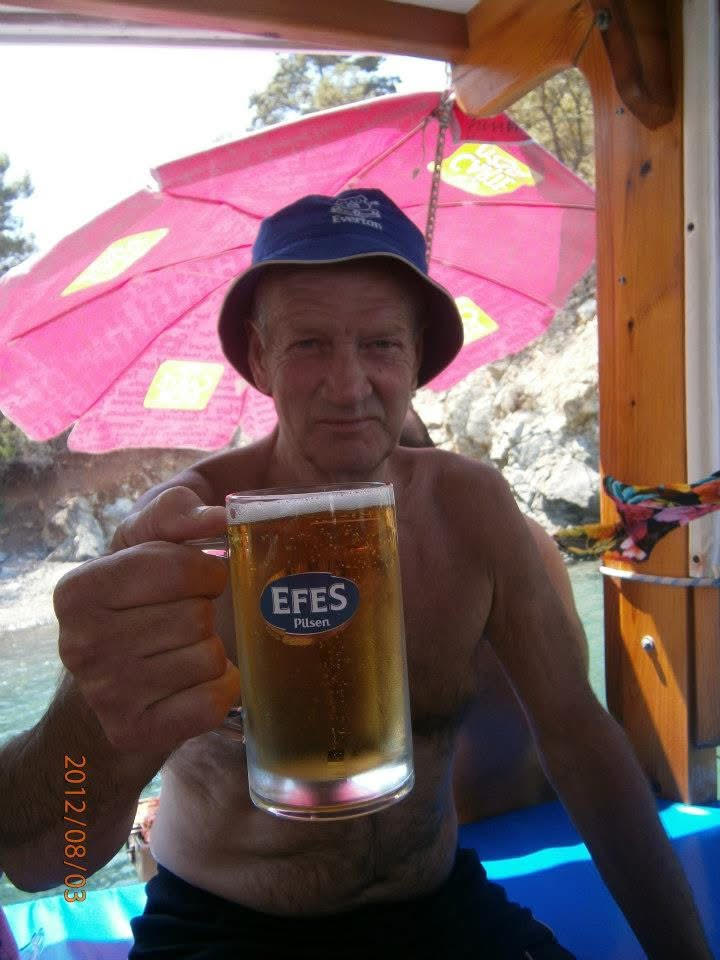

‘I am so upset about it. When I joined the club, Tommy and Colin Harvey were like a duo – they played in all of the teams together. He was a top footballer, full-back suited him so well. I can’t think of England having a better right back. There was no running away from him as he was so quick; I can’t recall a winger giving him a hard time. He had pace, strength and honesty. He wasn’t a great goalscorer, but he was up and down the pitch. He was a proper chap, one of the lads who enjoyed having a drink. He used to come into the manager’s room when I was back at Everton [in the 1990s]. He was a lovely guy; you couldn’t fault him – he never moaned or complained about anything. He was everyone’s friend and a one-club man.’

Tommy had experienced poor health in recent times. People connected to Everton would keep tabs on how he was doing and he was visited by Joe Royle and Colin Harvey last autumn.

Tommy Wright, one of the greatest yet most unassuming of all Evertonians, passed away on 20 January 2026. It was no surprise to see heartfelt tributes pouring in and there was a brilliantly observed minute of applause for him at the Everton home match against Leeds United.

I’ll leave the final words to Colin Harvey:

‘He was an outstanding footballer, but more important than that, Tommy was a really close friend and a lovely lad.’

Tommy Wright, Everton Giant, Rest in Peace.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Researched and written by Rob Sawyer

Photo research by Rob Sawyer and Mike Royden

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

With thanks to:

James Corbett

Gary Coxon

David Exall

Gerry Glover

Colin Harvey

Peter Hurn (Pete’s Picture Palace)

Mike Royden

Joe Royle

Billy Smith

Fran Thomas

Published sources:

Charles Buchan’s Monthly

Gwladys Sings The Blues

Editions of the Everton FC matchday programme

Various Merseyside newspapers

Ponting, Ivan, Everton: Player by Player (1992)

Corbett, James, The Everton Encyclopedia (2012)

Buckland, Gavin, Money Can’t Buy Us Love – Everton in the 1960s (2019)

Orr, George, Everton in the Sixties – A Golden Era (1997)

Online:

(Goodwin, Chris, www.englandfootballonline.com

Smith, Billy, bluecorrespondent.co.uk

Liverpool Record Office, evertoncollection.org.uk

Johnson, Steve, evertonresults.com