Nicholas John Ross, the Victorian version of the present-day soccer superstar, was a man who captained both Preston North End and Everton. He was the most feared defender of his generation and was described by the leading Victorian sports journalist, J A H Catton, as being “the most brilliant back of his day, if not of all time. The best I ever saw.”

Nick Ross, born in Edinburgh on 6 December 1862, was the second child of stonemason Thomas Ross and his wife Anne who was a shopkeeper. The 1871 census revealed that the Ross family were living at 47 Potters Row, George Street Shops, in the old town area of “Auld Reekie”. There were six children in the family, namely: Mary (twelve), Nicholas (eight), James (six), Elizabeth, (four) and twin boys named George and John who were three months old.

By 1881, Thomas Ross had passed away and Anne, then sixty one, had moved her family to 43 West Richmond Street, where Nicholas listed his occupation as a slater. His brother James, then sixteen, worked as a gas fitter. It is around this time that the two brothers started to play association football in their native city.

Nick Ross began his career with a team that played under the name Hanover, which he captained before joining Heart of Midlothian in 1881. He took up the centre-forward position and represented them in several local knockout competitions that were designed to raise money for the local hospitals.

In the summer of 1883, at the invitation of a Mr T McNeil, who scouted the area on behalf of Preston North End, Nick moved south to join a team of players who were being put together under the watchful eye of a local militia soldier whose name was Major Sudell. He controlled the finances of two large cotton mills and was a member of the executive at Preston North End Football Club. The major frequently detailed Mr McNeil to return to the ‘land of cakes’ to sign more players, where amongst others, he obtained the signature of James Ross, the younger brother of Nick. His Preston side, nevertheless, was lagging behind the football clubs from the neighbouring town of Blackburn who had already lifted the nation’s top honour, the FA Cup.

There was, in this Mid-Victorian era, no Football League, so the team who won the FA Cup were considered to be the soccer ‘Blue Ribbon’ holders in England. Blackburn Olympic, in 1883, had already accomplished this by the time Nick Ross commenced his playing career in England. Blackburn Rovers next came to the fore and won the trophy three years in succession while Preston North End, during this period, were twice eliminated by the FA Committee on the grounds of professionalism. In 1886, with everything now in order, Preston, who were then captained by Nick Ross, again entered the contest and received an away tie with the Queens Park club in Glasgow. The game caused a stir in the ‘No Mean City’.

The match took place at the second Hampden Park where a crowd of 20,000 filled the enclosure to capacity while Cathkin Brae, which overlooked the location, was also covered with people. Every vantage point on the nearby tenements was also filled as Nick Ross led his players out of the pavilion and was given a warm welcome by the football-loving inhabitants of Glasgow. The match however, was to end in controversy.

The visitors, who proved too good for their hosts, were leading 3-0 when, during the final minutes, a hard tackle from Jimmy Ross led to a Queens Park player having to be carried to the pavilion. The incident incensed the crowd which, when the final whistle was heard, swarmed on to the playing area as the Preston players dashed for the safety of the pavilion.

They quickly formed a hostile mob in front of the building, which was guarded by members of the Queens Park committee and demanded the reappearance of Jimmy Ross. Things continued to look ugly for the visitors until a member of the Hampden Park ground staff produced an Ulster coat for Ross and helped him leave the building via the rear window. The Preston player, ‘by climbing walls, mounting ladders, running through brickfields and tenements, made good his escape.’ (Glasgow Herald) The crowd, having witnessed the incident, began to disperse, leaving all parties concerned to be at liberty to vacate the enclosure.

Having returned to the centre of Glasgow, the two teams later sat down together at a hotel that was the favourite howff of the Queens Park committee, where an excellent meal was consumed. During the speeches that followed, Nick Ross thanked his fellow countrymen for their hospitality, before the visitors boarded the horse-drawn conveyance that had been provided to take them to Glasgow Central railway station.

When they reached their destination, the Preston party found a howling mob of irate football fans waiting for them on the concourse. They immediately swept forward and surrounded Nick Ross demanding to know the whereabouts of his younger brother. The ‘polis’ then arrived and a burly sergeant took control. Telling fibs, he told the crowd that Jimmy Ross had been arrested and, at that moment was locked up in Strathbungo Jail to await his trial. He was, in truth, back in his native Edinburgh. The news appeased the crowd who then allowed the Preston party to board the train that was to take them home to await the draw for the next round of the contest.

Three weeks later, they were back in Scotland. The FA Cup draw had given Nick Ross and his team mates an away tie against a team of players from the small Dunbartonshire village of Renton. The Scots immediately applied to have the game transferred to Hampden Park, but the Preston committee, remembering their previous visit, rejected the proposal out of hand. The game would be played at the home of Renton at Tontine Park. The tiny Scottish community mobilised behind their football club and several improvements were made to the ground to accommodate the large crowd that was expected to attend to match. The weather however, proved to be a problem.

A heavy fall of snow three days before the event had covered the ground to a depth of four inches. The committee, helped by many members of the community, cleared it away but due to the harsh frost the playing surface was unyielding. Several tonnes of salt, followed by thick layer of sand were then applied to the surface of pitch in the hope of making it playable. The Renton committee, their hard work complete, then awaited the arrival of the referee.

The Preston party, having spent the night in Glasgow, arrived at the tiny branch-line railway station to find a large crowd had gathered to escort them to Tontine Park. There was a capacity crowd of 4,000 people inside the ground as Nick Ross and his players took to the field where some rather serious news awaited them. The referee, Morton P Betts, had inspected the pitch and declared that it was ‘not fit to stage an FA Cup tie’. The game could go ahead, but not as a cup tie. This information was conveyed to the large group of visiting journalists who were ordered to withhold it from the home fans. They were however, not deceived, and soon discovered the correct circumstances under which the game was being played.

It had been in progress for five minutes when the spectators invaded the pitch and demanded back their admission fee. The referee then took the players off the field while the Renton committee men tried to pacify their supporters. Eventually, after much deliberation, it was decided that the game would be played as an ‘FA Cup tie under protest’ and the crowd settled back behind the barriers. It ended in a 3-3 draw. The FA committee, having reviewed the protest, ordered the game to be re-played at Hampden Park where the admission fee would be doubled to deter any disruptive elements from attending. Preston North End, fearing a third expulsion from the tournament, reluctantly agreed.

The president of the FA, Major Marindin, arrived in Glasgow with several other leading officials, and took charge in the middle. There were around 10,000 in the ground to see him line up the players and inform them that any breach of the rules would not be tolerated. Preston won the game, which was played in a most orderly fashion, by a score of 2-0. Nick Ross and his players then continued on their FA Cup odyssey.

The next port of call was the Lyttleton ground in East London where the Old Foresters were beaten 3-0. It was then back to the capital to take on the Old Carthusians in a midweek game at the Oval Cricket Ground. There was a large fashionable crowd at the ground, some of whom, it was reported, ‘shrieked and screamed in an attempt to unnerve the visitors, with one top-hatted masher calling for his favourites to do anything to them‘ (Preston Herald). Carthusians took the lead but Preston equalised to force extra time. They then went on to win the game 2-1 before dashing back home, where Nick Ross and his men had four days to prepare for the FA Cup semi-final. The match against West Bromwich Albion took place at Trent Bridge Cricket Ground where Preston, who had taken an early lead, slowly faded and lost the game 3-1.

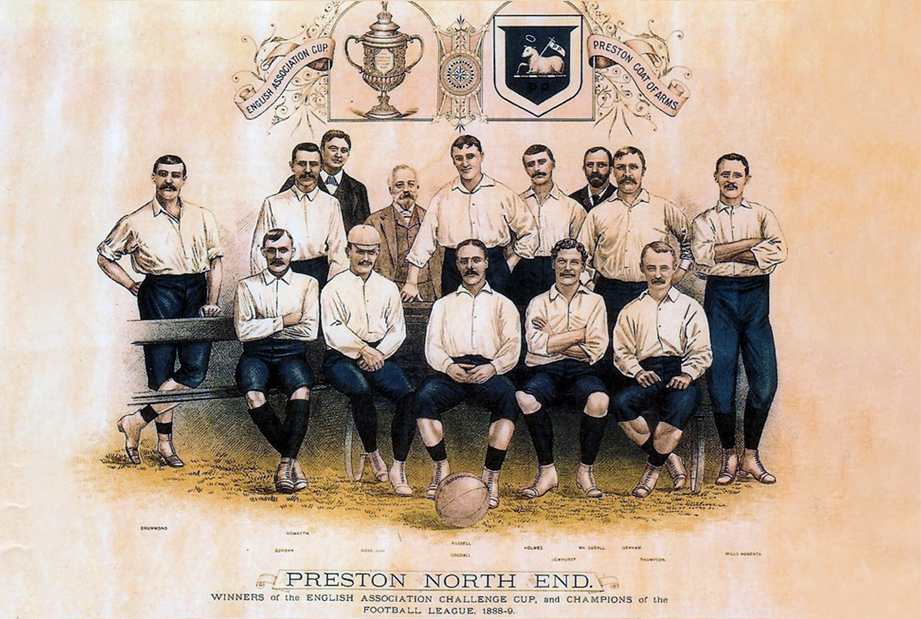

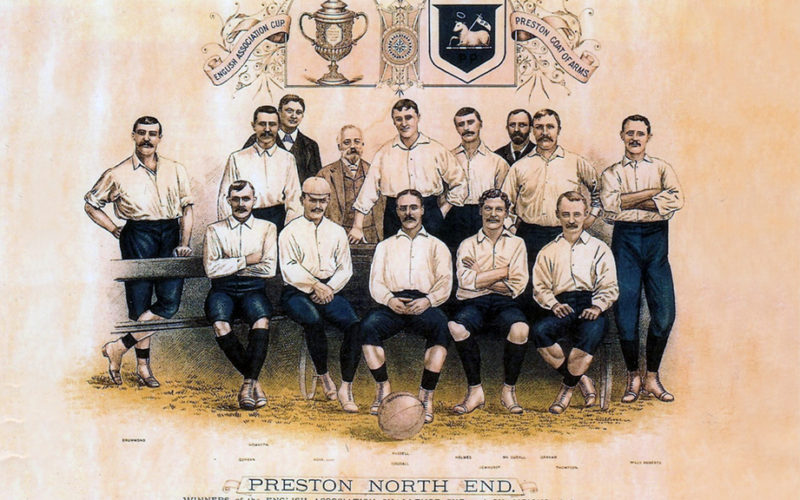

The following season, with Nick Ross again as captain, Preston North End began the FA Cup campaign with their record-breaking 26-0 victory over Hyde United. Everton, who were making their first visit to Deepdale, were then beaten in the next round by six goals to nil. Nevertheless, the Merseysiders were later fined for ‘professionalism’ and Preston were ordered to play the team Everton had previously eliminated, Bolton Wanderers. They beat them 9-0 to set up a fifth-round tie with Aston Villa, that was to produce scenes never before witnessed on a football ground in England.

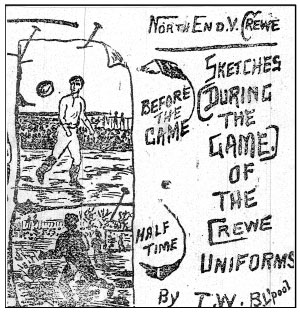

The reputation of Preston North End was growing in leaps and bounds and this drew a record crowd to the then home of Aston Villa at Perry Bar. The forty officers who policed the event could not prevent the spectators from pouring through the boundary ropes that surrounded the playing area. Nick Ross protested to the match official, but amid the chaos, play got underway. Several times during the match, the crowd spilled over onto the playing area and play was held up while the Aston Villa players implored them to keep back. Two mounted Hussars then arrived and rode along each touchline keeping back the crowd. The home side scored during the first half, which lasted for over an hour, but three second-half goals saw the visitor’s safely through to the next round where they defeated Sheffield Wednesday. They then met Crewe Alexandra in the semi-final at Liverpool.

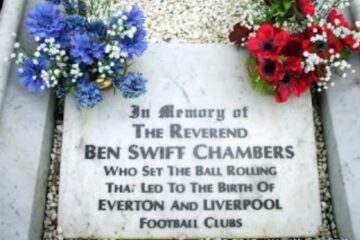

Ideally situated halfway between both towns, it was the first time that the Mersey seaport had been chosen to host the penultimate tie of the contest, but the occasion was ruined by the weather. The visiting fans arrived in Liverpool to be greeted by bright sunshine which, by kick-off time, had melted the overnight fall of snow and turned the grass playing surface to something that resembled the Mersey estuary at low tide. Nick Ross, who won the toss, decided to begin the game with the pronounced slope in his favour. His side then rattled in four first-half goals as the pitch deteriorated into a quagmire. The hopes of the Railwaymen throughout the second half slowly sank into the morass, leaving Preston, who added no further goals, the winners by 4-0. The players then changed at the Sandon Hotel and it was here, quite possibly, that Nick Ross was first approached by the Everton committee with a view to joining them at Anfield. First of all, however, he had to captain Preston North End in the FA Cup Final.

Their opponents were West Bromwich Albion and the match took place at the Oval Cricket Ground in London. The Lancashire team were favourites to win the trophy but, despite having the better of the play, they were surprisingly beaten 2-1. Several explanations later surfaced, one of which was that the Preston team had stood in the cold too long watching the Boat Race and this made them struggle to find their form. One or two strange decisions by the referee have also been mentioned. The affair had been a disappointment for Nick Ross who then surprised the Victorian football world by accepting an invitation to join Everton in time for the inaugural season of the Football League.

Stories began to circulate in the media as to why he had left Deepdale and joined a side that had yet to establish themselves as a force in the north west of England. The truth later emerged that they had made Ross an offer he found difficult to resist. His wages, around £10 per month, made him the highest-paid football player in the kingdom. It was W E Barclay, the Everton secretary, who secured his signature and he immediately appointed him to the role of club captain. Ross then made a surprise appearance, playing in a practice match on an unenclosed field on Belmont Road in Liverpool. There was a small amount of people present at the kick-off, but the number soon grew to around 3,000 as the news was circulated amongst sports fans who were spending the afternoon at nearby Stanley Park. Edgar Chadwick, a new signing from Blackburn Rovers, also took part in the game as did Jonny Holt who had just joined Everton from Bootle. The local football fans were delighted by the chance to catch a free glimpse of the new Everton signings and chat to them on the way back to the Sandon Hotel. Nick Ross then played a couple of warm-up games inside Anfield before the new Football League season commenced.

Everton began their Football League campaign with a 2-0 win over an Accrington side that arrived at the ground twenty minutes after the time appointed for the kick off. Nick Ross played at full-back and the number of people who attended the game, estimated at 12,000, was the largest crowd of the day. He formed a partnership at full-back with fellow Scot Sandy Dick, who had previously played for Kilmarnock Athletic. In the next game, at home to Notts County, Nick Ross scored his first Football League goal as Everton won the game 2-1. Nevertheless, a run of poor performances then saw him pressed into the forward line of an Everton side that was struggling to score goals.

The Merseyside club, who were serving a one-year ban from all knockout tournaments, were hoping to challenge for the League Championship, but as Christmas approached, they were well out of contention. The club that Ross had left to join Everton, Preston North End, were top of the league when the two sides met at Deepdale on 22 December 1888. The game attracted a crowd of 7,000 people who applauded Ross when he took the field and shook hands with his former boss, Major Sudell. He then lined up against his younger brother Jimmy as Everton, who were outplayed from the start, lost the game 3-0.

The Preston club had already clinched the first Football League title when the sides met again four weeks later, before an enormous crowd of spectators at Anfield. At an estimated 15,000, it was the largest crowd to date to watch a Football League match in England. Everton held the fearful opponents at bay for nearly an hour until a goal by Jimmy Ross finally broke the deadlock. A second goal was then added by John Goodall as Preston ran out 2-0 winners. It had been yet another defeat for an Everton side that had scored only four goals since the first day of December.

Nick Ross, it would appear, was not happy in the forward line, preferring to play instead at full-back as he had with Preston. There was however, a certain incident, prior to the home game with West Bromwich Albion, which may have made him decided to leave Everton and re-join his brother at Deepdale.

The teams were about to kick-off when the visiting captain complained to Nick Ross that the ball was not spherical and asked if a replacement could be found. The Scot then took the ball over to where the club directors were seated on the grandstand and informed them of the protest. He was promptly told to, “mind your own business and go to your place. All you are required to do is play the game.” Everton went on to lose the game 1-0, the rebuke however, was witnessed by an unidentified individual who, being annoyed by the incident, wrote a letter of protest that appeared on 28 February 1889 in the Liverpool Courier. He described the man, whose remarks he had overheard as being, ‘one of the leading spirits of the management committee’, but stopped short of mentioning him by name.

Whether this incident convinced Ross that it was time for a change is open to conjecture, because he missed the last game of the season against Blackburn Rovers. He then represented Everton in several friendly games before leaving the club at the end of the season. Ross spent the summer months in Belfast coaching the Linfield club before returning to re-join his brother at Deepdale. He had played nineteen Football League games for Everton and scored five goals.

During the summer, Everton had made a series of ‘big name’ signings that put them in a position to challenge Preston North End for the League Championship. On 16 November 1889, Nick Ross was back at Anfield, where he received a warm reception when he led the visitors on to the field. The occasion filled the ground to capacity with many more locked outside the gates. The weight of the crowd as the play progressed became too great for the barrier behind to goal and it collapsed, sending hundreds of spectators spilling on to playing area. Luckily, nobody was killed.

The much-improved Everton side began the game well and had a 1-0 lead at the break. The tempest then broke and the visitors, in the course of the second half, scored at regular intervals to win the game 5-1. Everton then surprised Preston by beating them 2-1 in the return game at Deepdale but could not prevent Nick Ross and his team from carrying off the Championship trophy for the second time in succession. It was, however, the only medal that this talented Scotsman was to win.

The next season, after a hard fought battle, his North End side was pipped to Championship by Everton. The Merseysiders, backed up by a board of energetic local businessmen, had now become the best-supported club in Victorian England and this enabled them, by paying good wages, to import some of the best players Scotland had to offer.

Preston North End, meanwhile, continued to challenge for the Championship but, by the winter of 1894, the health of Nick Ross was beginning to deteriorate. This fact became apparent during an FA Cup tie played at Deepdale against Reading. The home side were leading 12-0 when a heavy shower of rain burst over the location. Ross, who was recovering from a bout of influenza, was persuaded, by the club executive, to take shelter in the dressing room until the rain stopped. The Scotsman, accompanied by loud applause, then re-joined the game as the home side went on to win the tie 18-0. His health however, was still giving cause for concern and before that season ended the club had decided to send him on a cruise to a warmer climate.

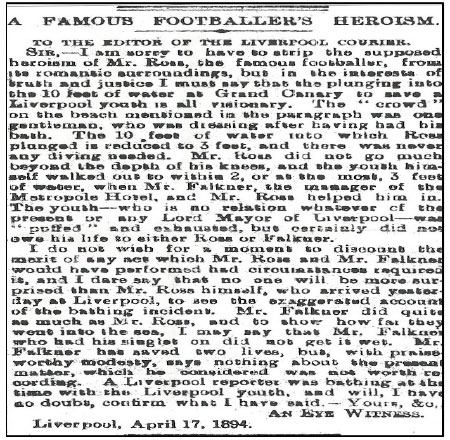

Nick Ross left Liverpool aboard the SS Benin and seven days later put up at Hotel Metropole in Las Palmas. He remained there for one week before returning to Liverpool aboard the SS Benin on its homeward voyage. During his time in Grand Canary, the Scotsman was involved in a sea rescue which, it later transpired, was blown up out of all proportion. Nevertheless, the incident reached the ears of a Preston-based journalist who, after an interview with his wife, penned the following article.

Mrs Ross has just received news information of a gallant rescue that was effected by her husband while recuperating his health in Grand Canary. Sensation – Ross – the hero of the hour. A dance was arranged in his honour but, after declining to attend, he left Las Palmas on 10 April aboard the SS Benin.

Lancashire Daily Post, 17 April 1894

The newspaper report, it would appear, embarrassed Ross, who on his arrival back in Preston, made straight for the local newspaper office and asked the Editor to issue the following statement.

Sir, there was nobody more surprised than myself when I arrived in England yesterday to find glowing and erroneous accounts of a very simple incident that occurred during my stay in Las Palmas. In fact, I was very much annoyed that publicity had been given to the matter. I take no credit myself for assisting young Holt to get out of his dangerous position in the sea and I consider that I only did my duty. Nicholas John Ross, Fishergate Chambers, Preston.

Meanwhile, over in Liverpool, a man who had witnessed the event was interviewed by a local journalist and this resulted in the following item to appear in the Liverpool Courier.

Ross spent the summer recuperating on the Fylde coast and also purchased a cottage on Longridge Fell, where he hoped the fresh air would help him to full recovery. Alas, this did not happen. In early August he was again confined to his bed at his home at 34 Berry Street where he was treated by the club doctor. On the morning of 7 August 1894, he felt well enough to move about the house for a while but then suddenly collapsed and died.

Nick Ross had touched the hearts of everyone in Preston and news of his sudden death shocked the whole community. His funeral cortege, which left his home on 10 August 1894, brought the cotton mill town to a standstill. The blinds and shutters of each house were drawn and thousands lined the route as the horse-drawn hearse slowly passed through the town on the way to chapel at Preston Cemetery. Here, a short service was held before several former teammates carried the coffin of Nick Ross to its last resting place. He was just thirty one years old.