Football and showbiz have been bedfellows since the early days of the sport. Before the dawn of the 20th Century, theatrical matches were staged at Everton’s ground. In the 1920s, Jack Cock combined spearheading the Blues attack with treading the boards in music hall, subsequently trying his hand at movie acting. In 1968, the Golden Vision play, screened on the BBC, immortalised Alex Young on celluloid. More recently, the Toffees’ late chairman, Bill Kenwright, was a successful and high-profile impresario in the world of theatre. Other football clubs have, of course, had strong links to the entertainment business. Chelsea’s chairman for a number of years was Richard Attenborough, Eric Morecambe was on the board at Luton Town and Tommy Trinder was closely associated with Fulham FC for many years, serving as the Cottagers’ chairman between 1959 and 1976.

A show business link between Craven Cottage and Goodison Park was George Robey. Born George Wade, the Londoner, who had spent much of his adolescence in Germany, had debuted on the stage in 1891 and attained fame in music halls and theatres for his comedic star turns. His on-stage personas often used heavy applications of make-up and wigs – his signature act being a character called The Prime Minister of Mirth (with trademark small bowler hat and walking cane). Maybe ahead of his time, it has been said that his performances mixed everyday situations and observations with comic absurdity (Vic and Bob, anyone?).

Robey was an able and keen all-round sportsman. He was a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club and turned out for Millwall FC as an inside-forward on a number of occasions (generally in friendly fixtures). The star also liked to organise exhibition soccer matches which raised money for charities, often when he was on tour around the country.

Always a big pull in pantomime, over the festive season of 1905, he had the titular role (in drag) in a Liverpool staging of The Queen of Hearts. While on Merseyside, he took the opportunity to arrange a match against the Toffees on Valentine’s Day 1906. The Everton FC Board minutes of 18 January 1906 record:

Robey’s Match

Resolved we arrange to play Robey’s team a match but not necessarily with our league team: the receipts to be handed to Geo Robey’s charitable funds.

Robey advised the Blue’s directors that he proposed to allocate 5% of the gate takings to General Booth & the balance to the Theatrical Gala Fund.

Using his connections in sport, he put together a Robey XI comprising Chelsea, Manchester City, Liverpool, Preston and Derby County players. Steve Bloomer (the man who would go on to give Everton its School of Science sobriquet) was one notable participant. A few days before the big match, he warmed up in a Royal Court Theatre XI which took on a team mainly composed of Old Xaverian players at Clubmoor. The theatrical team went down 3-1 but Robey, playing at centre-forward, got the consolation goal.

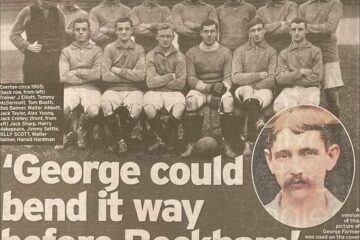

On Goodison Park matchday, the sun shone and in the region of 12,000 people made their way to the stadium (although not all had made it through the turnstiles in time for the kick-off). In spite of being in the middle of a season of competitive fixtures the Toffees fielded a relatively strong XI, featuring Billy Scott in goal, Jack Crelly at full-back, captain Jack Taylor at centre-half and the likes of Jimmy Settle, Sandy Young and Harry Makepeace also featuring. Naturally, Robey made himself captain of his side and was seated front, centre in the pre-match photo. Also in shot were Billy Meredith, the legendary Wales and Manchester City player (serving a season’s ban for attempted bribery), Jack Sharp (the Everton winger who was rested, having scored a hat-trick in a home defeat of Sheffield United four days previously) and Jack Elliott, trainer to the Toffees.

On the pitch, it was a hard-fought encounter. Sandy Young had twice failed to convert for the Blues when well placed. Robey was outclassed by his teammates and his mis-controlling of the ball and poor distribution greatly amused the crowd. Although spectators guffawed, there was confusion as to whether Robey’s ‘bloopers’ were genuine or for comic effect – the former is far more likely. The barrackers were made to eat their words when the comedian opened the scoring for the visitors. Billy Scott could only half-clear a shot and Robey, in the words of the Evening Express, ‘rushed the ball into the net.’ He had a chance to double the lead when released by Raisbeck but, according to the Liverpool Courier match report: ‘the captain sent the ball in the direction of his own goal.’ Jimmy Settle equalised for the hosts before the break with a neat finish just inside the post.

In the second half, the visitors edged in front again before Hugh Bolton drew the Toffees level. However, on a muddy pitch, with the wind at their backs, Robey’s XI scored three late goals to make the final score 5-2 in their favour. As a postscript, 11 months later Robey approached Everton to release Harold Hardman and Harry Makepeace for another of his charity matches. The directorate declined the request.

Robey would have a long career in show business, touring his revue extensively and even appearing on stage as Falstaff in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1 – a role he reprised in a Lawrence Oliver film in 1944. He appeared in several films, with moderate success, and kept working through the Second World War years, and beyond.

George Robey, comedian, singer, actor, charity fundraiser and sportsman was knighted a few months prior to his death in November 1954. The 85-year-old had a stroke and died a week later, in his second wife’s arms, clutching his famous walking cane, at his home in Saltdean, Sussex. When his passing was announced (front page news in many newspapers), tributes flooded in. His memorial service, held at St Paul’s Cathedral, was attended by a diverse congregation which included royalty, people from theatreland and many other parts of society.

Acknowledgements

The Sharp family for the Robey XI photo

National Portrait Gallery

Billy Smith, bluecorrespondent.co.uk (newspaper reports)

Steve Johnson, evertonresults.com

Wikipedia