by Rob Sawyer

‘He played anywhere readily and played well anywhere. No Everton player has left Evertonians with a more fragrant memory.’

Thomas Keates (1928)

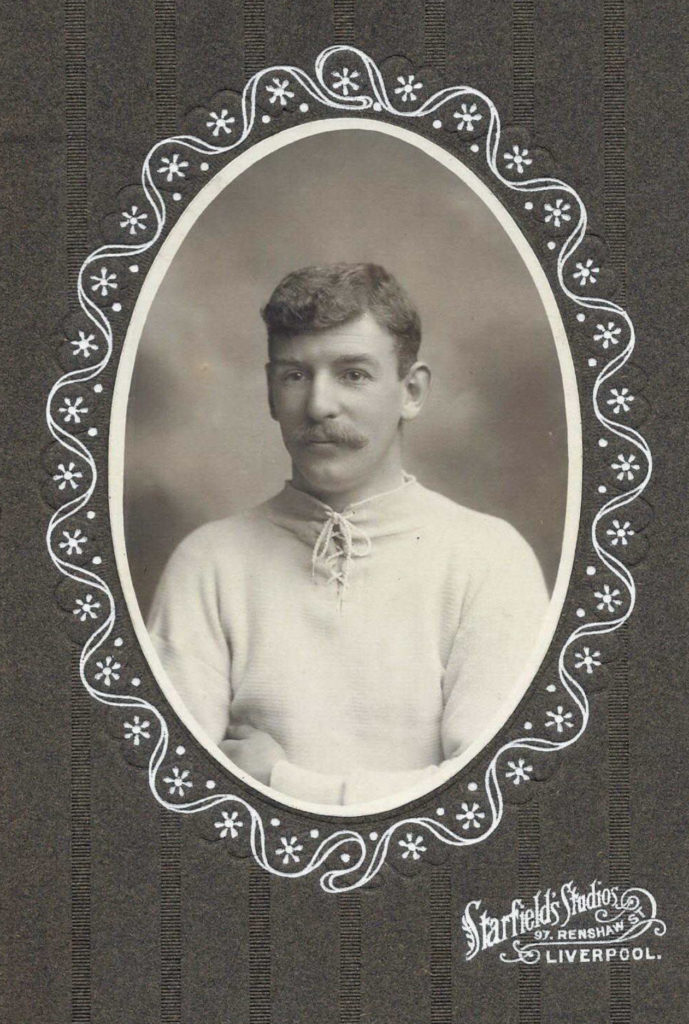

There must have been something in the water in Dunbartonshire in the second half of the 19th century. Between 1889 and 1897, six footballers with strong connections to the Clydeside town of Dumbarton represented the Toffees. First there was Alex Latta, followed by Richard ‘Dickie’ Boyle, Abe Hartley and the Bell brothers (John and Laurie). But only one, John ‘Jack’ Taylor, would get his hands on silverware whilst associated with the Toffees – albeit after an agonising series of near-misses. One of the true greats of Everton’s early decades, this moustachioed ‘Jack of all trades’ remains Everton’s seventh highest appearance maker in all competitions.

John Daniel Taylor was born at Dumbarton’s 19 Clyde Street, on 27 January 1872 (although he was known in family circles as John – this article will refer to him as Jack, the derivation used in most press reports of the era). He was one of three boys and three girls born to Ann (née Hutchison) and James Taylor (a ship joiner). After joining Newtown Thistle FC at fifteen, a year later he signed for Dumbarton FC, the senior club in his hometown, dubbed The Sons of the Rock.

Always a versatile player, he switched from half-back to the forward line and returned a goal average of better than one every other game. By the time he was 20 he had two Scottish League titles under his belt. The inaugural competition, in 1890/91 saw Dumbarton tie on points with Glasgow Rangers. A play-off ending in a 2-2- draw failed to separate them so the title was shared. The subsequent year, Jack and colleagues saw off the challenge of Celtic and Hearts to become undisputed champions. His reward was a Scotland debut in a 6-1 thrashing of Wales in March 1892. He’d three more caps – the last three years after his debut – scoring one goal. The chances of winning further caps were hampered by his eventual move away from his homeland.

Success for Dumbarton would quickly evaporate. The club was slow to embrace professionalism, and many star players left to earn a living in England or elsewhere in Scotland. When Jack, who’d been employed as a marine engineer, moved on from Dumbarton, he eschewed a move south of the border, switching to Paisley’s St. Mirren FC in 1894.

In May 1896, however, the lure of English football was too much to resist and he joined Everton on wages of £4 per week, plus bonuses. A man by the name of Littler was minuted by the Toffees board as having received a finders/facilitation fee of £10 – proof that agents and middle-men were not entirely an invention of the late 20th century. On Jack’s debut for his new club, in a friendly fixture against Glasgow Rangers, he garnered a rave review from the Liverpool Mercury:

‘Taylor, by his really excellent display, justified all the good things that have been said, and written concerning his abilities, and judging by the readiness and ease with which he adapted himself to strange surroundings, he will undoubtedly prove a most valuable acquisition.’

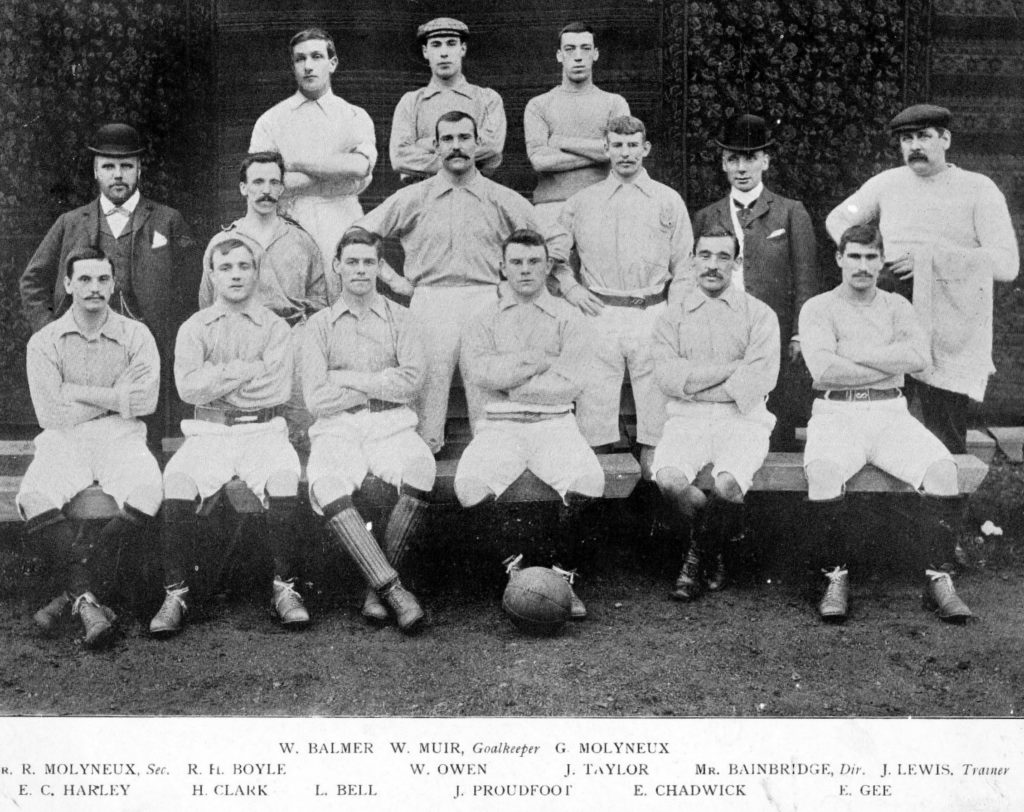

He went straight into the Everton Football League team as an outside-right (right winger) – joining familiar faces from Dumbarton in John Bell and Dickie Boyle. With Bell operating at outside left, Everton had one of the most devastating flank pairings in its history. Like Bell, Jack was quite tall for the wing position but was described as ‘lissom’ in contemporary reports. As the season progressed he was switched to an inside-forward role. Making the most appearances of any player (thirty-five), in his debut season, he gave a creditable goal return of fifteen goals. Although Everton’s league form was mediocre, the team advanced to the FA Cup Final against Aston Villa, staged at Crystal Palace.

It was a stirring match with Everton on the wrong end of a 3-2 scoreline – the Blues undone by defensive weaknesses. Jack and teammates gave their all in search of the equaliser that never came. The Liverpool Mercury reported:

‘It was a magnificent finish, and nobody would have grumbled had Everton’s gallant efforts to equalise been rewarded. The match was admitted to be the best final tie ever played in the English Cup competition, it must be confessed that the Villa were slightly superior in the first half, and possibly deserved the advantage of a goal. At the same time the magnificent fashion in which Everton forwards backed to their work after being twice in the arrears was heartily recognised by the crowd.’

The 1897/98 season saw Jack joined by another familiar face from back home in Laurie Bell, brother of John, but the season followed a similar pattern to the previous one. The Toffees once again ended the season in mid-table and fell a hurdle earlier in the cup, losing a semi-final to Derby County. Jack was predominantly deployed on the right wing but was occasionally asked to fill-in as a wing-half – a taste of things to come. The 1898/99 season saw him selected as a left-sided wing-half, and even on occasion a centre-half, before he was restored the right wing in the spring. His natural leadership skills saw him elevated to club captain in the 1899/90 season. Newspaper items such as below underline why he was an obvious choice to lead the team:

‘Did anybody ever see John D. Taylor “loofing” in a match? The answer to that question can only be a decided negative. His style of play was like Bell’s, forceful, but fair. He had not the sheer driving force that carried Bell through every obstacle, nor had he quite the same command and control over the ball, but he more than equalled those deficiencies by dash and agility that no other player in the team could equal. Further, and much more valuable in a forward, he never tired, and was absolutely fearless, no matter what the odds opposing.

‘Like a rushing wind he would come, in perfection of speed, stamina, and grit, and only a better player could dispossess him. His resolute bearing often disheartened an opponent who realised that the fair-haired Scot had not only speed and weight behind the ball, but also a skill born of many hard fights on English and Scottish fields. It has often been commented on that the driving power of Taylor’s personality in any team in which he played communicated itself in some way to the whole side. No player could play “easy” or show dalliance in a game in which the war-horse, as Everton affectionately called him, took part.’

It seems surprising that, after just one season, Jack stood aside for Jimmy Settle to be skipper. At the turn of the century, no longer considered a winger, he was switching on an almost week-by-week basis between either of the inside-forward roles and both wing roles. In the early 1900s, the Toffees’ side was reinforced by the arrivals of winger Jack Sharp and centre-forward Sandy Young – plus the return of John Bell. Jack was predominantly played at inside-right, combining with Sharp and Young on the right of attack. Bell, meanwhile, patrolled the left wing. Thomas Keates, in the first history of the club published in 1928, lauded the contribution of Bell, Sharp and Taylor:

‘Their high standard code of life, mentality and lingual purity had a most beneficial influence on the habits and tone of their players – and the influence did not cease with their exit.

In 1901/02 the Blues came up just short in the race for the title, finishing runners-up up to Sunderland. Two seasons later they came third and then, in 1904/05, it seemed that Jack would be rewarded for his dedication and consistency. He was the sole ever-present (switching from wing-half to centre-half – two very different roles) as the Blues enjoyed a fine season. However, glory was cruelly denied the Merseysiders by the London smog. The Blues were winning against Woolwich Arsenal only to see the match curtailed with only a quarter of an hour left to play as the ‘pea souper’ thickened. In a fixture pile up at the end of the season, entailing six games in nineteen days, the fatigued Toffees lost on consecutive days to Manchester City and Woolwich Arsenal (the latter being the rearranged match). So, the valiant Blues, who had gone out of the FA Cup after a replayed semi-final against Aston Villa, finished the season just a point shy of Newcastle.

It seemed that the veteran Scot was destined never to get his hands on a trophy with the Toffees. But just a year later, all that had changed. A poor season in the League was compensated for by the Blues reaching the FA Cup final – staged at Crystal Palace – the opponents were to be the side who had pipped them to the title in 1905 – Newcastle. In the absence of club captain Tom Booth, Jack proudly skippered the side in a tight match which was settled when he fed Jack Sharp who, in turn, crossed for Alex Young to convert. A proud moment for the Scot – this was Everton’s first FA Cup victory.

Arriving back at Liverpool Central railway station, the team was greeted by a throng of supporters and dignitaries. The Lord Mayor delivered an impromptu congratulatory speech from the top of a truck. Then, on board a four in-hand horse-drawn carriage, with a mounted police escort, the players paraded towards Goodison Park – Jack in the driver’s seat – waving the trophy at the people lining the streets on the route via Byrom Street and Scotland Road. At the stadium more celebrations, toasts and speeches followed before the elated, but exhausted players could head home.

Given the club captaincy on a permanent basis, until Jack Sharp took it on in 1908, Jack continued to give loyal, doughty service to the Blues cause even though he was into his mid-30s. He led the team to another FA Cup final the following year – losing to Sheffield Wednesday, and came close to adding the English League title to his list of honours, but the Toffeemen came up short in 1909, five points behind Newcastle in spite of an impressive goal haul, led by Bertie Freeman with thirty-eight. After that season ended, Jack was part of the Blues’ party which sailed with Spurs to play matches in South America – inspiring the formation of our Everton cousins in Chile.

Although not selected for every match in the following campaign, Jack continued to perform with his customary application when called-upon as a centre-half. In doing so, he became the first Everton player to reach the 400 League appearances mark. He was present for yet another cup semi-final when the Blues drew with Barnsley at Elland Road. In the replay, at Old Trafford, his first class football career came to a juddering end when he was caught on the throat by a stray Barnsley boot, just fifteen minutes into the match. The Liverpool Echo reported: ‘At first the impression was that he had swallowed something…He was obviously suffering, and after Dr Baxter and Dr Whitford had examined him in the dressing room, it was seen that he would be unable to take any further part of the match. His larynx had been injured and it was with difficulty that he could speak.’ With Billy Scott also injured – the webbing between the fingers in one of his hands being split – the Toffees went down to a 3-0 defeat.

Effectively, his first class career was ended by that high boot but he remained on the club’s books for two further seasons, appearing for the second-string but not adding to his 456 senior outings. He also did a spot of scouting for young talent to bring to Goodison Park. He qualified for a long-service benefit in December 1911, before being released on a free transfer in the spring of 1912.

Thomas Keates, in his history of Everton stated that the stalwart was ‘one of the most loyal, energetic, and gifted players the Club ever engaged. The majority of players jib at being moved about from one place to another in a team, arguing, quite truly, that it tends to deterioration. It is unavoidable at times. Jack Taylor was an exception. He played anywhere readily, and played well everywhere, and had a fine record during his 13 years’ service.’

Still itching to play the game he loved, Jack was engaged by Robert Alty and W.J. Sawyer at Lancashire Combination South Liverpool FC; they paired him with old comrade Sandy Young (Bob Balmer was another former Toffee finding his way to Grafton Street). Now in his early forties and still, one would imagine, hampered by the long-term effects of his throat injury, he still made an impact at this ambitious club as this profile in a matchday programme from 1913 underlines:

We know of no finer specimen of a professional footballer than the subject of our sketch. To the thousands of followers of the winter game in Liverpool, the name of Taylor is a household word, and a more popular player exists not in this city at the present time…Since he came to Liverpool he has developed into one of the most noted Scots that has ever crossed the Border…It is gratifying to see such a player as Taylor still able to maintain his place in a team like ours. He has been a most valuable servant ever since he joined us, and his zeal is an object lesson to any youthful performer who desires to become famous in football. A more whole-hearted player never took part in the game, and it is surprising to find him still turning out fit and well, and as keen on the game as in his youthful days. We want more men of his stamp in football, and the sport will be the loser when the time comes for him to finally retire – that is if he ever will consent to acknowledge the inevitable claims of Anno Domini.

He left South Liverpool at some point in the 1913-14 season, but had a swansong with Borough of Wallasey FC (sometimes also known as Wallasey Borough). Away from the dying embers of his distinguished playing career, Jack ran a newspaper-cum-tobacconist business at 197 Walton Road, a short distance from the current location of Everton in the Community’s Blue Base on Salop Street (the shop is still there facing the Queen’s Arms). While serving at the counter he’d have heard the roar from ‘Toffeeopolis’ – no doubt prompting wistful thoughts. He sold the shop in the spring of 1917 – the newspaper listing for the business describing it as ‘an old-established newsagent, tobacconist, toy and fancy business in a good position’. At this point he drew on the engineering skills that he’d learned as an apprentice on Clydeside – probably working at Liverpool docks. With his wife Elizabeth (nee Goudie) he’d had six children: Isabella, Anne, Elizabeth, Lorna, James and Joan.

After the war Jack worked as a construction engineer on the new Gladstone Dock, then, in 1930, after a two-year period of unemployment he became an insurance agent. He was always welcomed back at Goodison Park as one of the club’s first genuine greats – and was always made welcome by Liverpool FC too. Naturally, Jack was an invite to the Toffees’ 50th anniversary celebration dinner held in 1928.

Perhaps inspired by Jack, two of his nephews played football professionally. James (Jimmy) Carr was the second son of Jack’s sister, Agnes. He played for a number of teams (West Ham, Reading) between 1913 and 1928. After football, he ended up running a public house in Southlands, London. James Kerr Taylor, the son of Jack’s brother, Robert had, a short football career with Dumbarton FC from June 1921 to September 1922 (he subsequently emigrated to the USA).

In later life, Jack and his wife Elizabeth resided at 69 Grange Road, West Kirby and it was there that they celebrated their golden wedding anniversary on 28 October 1947 – Jack was still recognisable in photos for his moustache which he’d retained, long after it had been the height of fashion in the late Victorian era. The couple did not forget their roots, naming their house ‘Alclutha’ – a Celtic name for Dumbarton, which literally means ‘The Rock on the Clyde’. Shortly before the outbreak of war, with Everton on the cusp of another League title, Jack was interviewed for the Topical Times magazine and offered his views on the development of the game. He felt that the sport had lost some of its individuality and that some fans derived their main entertainment from thoughts of potential pools dividends. Whilst acknowledging that some might find his views to be those of an old fogey, he offered up his thoughts on modern players and wing-play, in particular:

‘I’m not one of your old-time growlers…but the greatest crime today is that a player passes the ball without looking. I would drill into my boys the necessity of looking before they deliver the pass. In addition, I wish wingers would get on with their job of making ground. Today the winger seems to get the ball and find it very “hot”; he wants to pass to his half-back behind him, or to his inside-forward, and then ask for it to be put forward again, at which point he hesitates before he centres. The winger is up there to make ground, to go up, and up, and up, and then deliver the centre…Nowadays they hang on and on, as if the ball belonged to them.’

On the Wirral he’d become a keen spectator of Deeside Rovers, deriving great pleasure not only from watching them but through passing on sage advice to the young players. His cheerful disposition and good sense of humour made him popular with the boys. In his later years he was Vice-President of the club, and at the time of his passing, President-Elect. He survived a nasty motoring accident in 1947, making a stirring recovery which was typical of the man. Jack’s grandson, Bill, was born at the end of the Second World War and has a few memories of his grandfather:

‘At the age of four, I can remember that he took me for a walk into West Kirby to look at a toy shop. In the front room of the house in Grange Road there was a glass fronted cabinet which contained all his caps and medals. When his son James married Elizabeth, the Everton players etc. presented them with a marble clock and two decorative vases.’

Early in 1949, Jack was taken ill and confined to bed for a number of weeks. One of Everton’s first true greats, he passed away in his sleep on 21 February of that year, aged seventy-seven. He was laid to rest at St Luke’s church cemetery in Crosby.

(with Rob Sawyer and Jamie Yates of EFCHS, off camera)

In December 2019, Jack’s great-granddaughter, who had carried out considerable research into the family history, came over from Canada with her husband and two sons to visit Jack’s grave and old stomping ground. They were guests of Everton FC and Everton FC Heritage Society for Carlo Ancelotti’s first match as manager (a defeat of Burnley) – and briefly got onto the pitch before the match. They were also able to reconnect with other family members still residing in the UK, including one of Jack’s grandsons.

As with his compatriots, John Bell and Dickie Boyle, Jack’s inestimable contribution to the Blues’ cause has been acknowledged through induction into Gwladys Street’s Hall of Fame. However, I hope that one day the club will bestow the ultimate honour of Everton Giant status on this Son of the Rock who made Merseyside his home.

I’ll leave the final words to the inestimable Thomas Keates, when describing the legacy of the ‘three Jacks’ – Bell, Sharp and Taylor, plus Dickie Doyle and several others:

‘The stars in the old brigade were numerous, and shine still in memoriam. Most of them are “but phantoms now, their day is done, yet a dreamy vision of them lingers in the place where once they were.”’

Acknowledgements:

My sincere thanks to the Elce-Darragh family for encouragement and support in telling Jack’s story.

Sources:

Elce/Taylor family archives

The Crabtree family

Jamie Yates (Everton FC Heritage Society)

Jim McAllister (Dumbarton FC historian).

Everton FC Heritage Society

Billy Smith, bluecorrespondent.co.uk, transcribed newspaper reports

Steve Johnson, evertonresults.com (Everton statistics by EFCHS member)

Thomas Keates, History of the Everton Football Club 1878-1928 (1928)

James Corbett, The Everton Encyclopedia (2012) (EFCHS member)

The Everton Collection, www.evertoncollection.org.uk

Jim McAllister, The Sons of the Rock -The Official History of Dumbarton Football Club (2002)

Hyder Jawad, Rest in Pieces: South Liverpool FC 1894-1994 (2014)