Jamie Yates of Everton FC Heritage Society, who researched the story of George Farmer and directed the project, writes;

Why George Farmer?

Without the philanthropy of Everton Football Club and the local community around Liverpool 4 and beyond upon the death of George Farmer in May 1905, it is not unreasonable to assume that his widow and eight young children would not have survived the poverty-stricken future they were facing.

Without George Farmer capturing the imagination of thousands of Evertonians – not to mention the thousands who went along to watch football for the first time in that era with no idea that they would leave Anfield as newly converted Evertonians – Everton Football Club might well never have made it to the level of Football League founder members.

Farmer’s story serves as a reminder of where we came from, why it means so much, and always has. He was the archetype for every great Everton hero who followed.

Jack Wildman grew up in Everton, and was a playing founder member of the St Domingo’s Church football team in 1878. Late in his life he wrote to the Liverpool Echo in 1925:

‘I think the first import was George Dobson from Bolton, then George Farmer from Oswestry, and I think if there is to be a monument or a tablet fixed on Everton’s ground, George Farmer’s name should be in the centre. Farmer was the man that made the people come and take notice. We never looked back after he came.’

George Farmer was;

- Everton’s first professional ‘signing,’ alongside George Dobson, at the dawn of professionalism.

- The first international footballer to play for Everton (for Wales, just prior to joining Everton).

- The first Everton player selected by England (as a non-playing reserve) in 1887.

- Fourth on Everton’s pre-League appearance list with 134 appearances, .

- Second on Everton’s pre-League goal-scorers list with 81 goals. Joint 21st in the all-time list.

- First professional player to score for Everton in an F.A. Cup tie, in 1887.

- Created both goals for George Fleming on Everton’s Football League debut.

Further quotes from Liverpool Echo match reports and letters pages:

‘There is one little man that we all admired way back in the ‘80’s; he came from Oswestry, and his name was George Farmer. What a dandy little player he was! I resided at Toxteth Park (Dingle), and joyously walked all the way to the Sandon Hotel to obtain a close-up view of the favourites, Georgie Farmer and Dobson, the full back.’

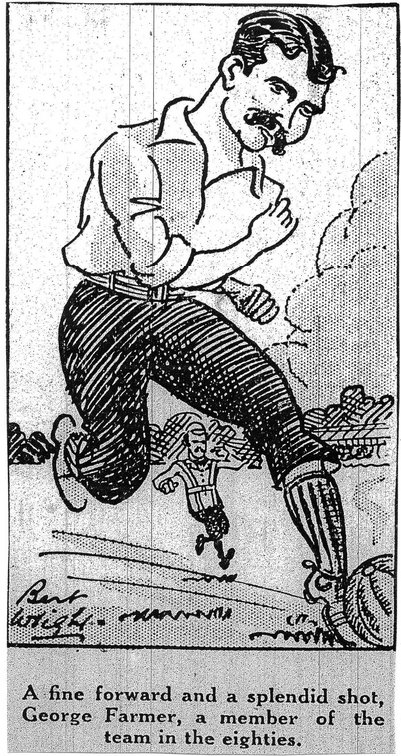

‘George Farmer, a left-footed, screw-kicking artist, and the veritable idol of the old Everton supporters.’

‘Although I have seen many celebrated players in their colours since, none of them have given me such pleasure as these. George Farmer I consider the finest inside-left I have ever seen, and Farmer, Dick, and old Mike Higgins, with clever Billy Briscoe, to my mind, laid the foundation of success of the Everton club, under the captaincy of George Dobson… these players should not be forgotten by the wealthy Everton club, and I am sure if any of the supporters of the old days are about they will confirm my remarks.’

‘George Farmer had a similar hearty greeting and cries of “Now Georgie,” “Play up George,” stimulated the arrival of Mr. F. T. Norris, the referee. The coin was tossed and North End, winning, placed their backs to the sun, Everton defending the Anfield Road goal.’

………………………………..

The George Farmer Story (abridged)

Jamie Yates

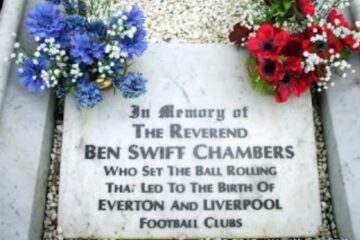

Everton-specific books, and football histories in general, often record George Farmer, alongside George Dobson, as Everton’s first professionally contracted player. Some include the fact that he came from Oswestry and played twice for Wales in 1885. Otherwise, very little exists in print about the Everton careers of either Farmer or Dobson. In fact, there is no entry whatsoever for George Farmer in the ‘Everton Encyclopedia’, published in 2012. Scottish full-back ‘Deadly’ Alec Dick is listed alongside Dobson as Everton’s first professional, despite the fact that Dick signed for Everton some 18 months after Farmer, and Dobson arrived at Anfield in April 1885. Farmer gets a passing mention at the end of Dick’s profile, as a benefit match was staged for early Everton heroes Dick, Farmer and goalkeeper Charles Joliffe in March 1891, all of whom lie in unmarked graves in Anfield Cemetery.

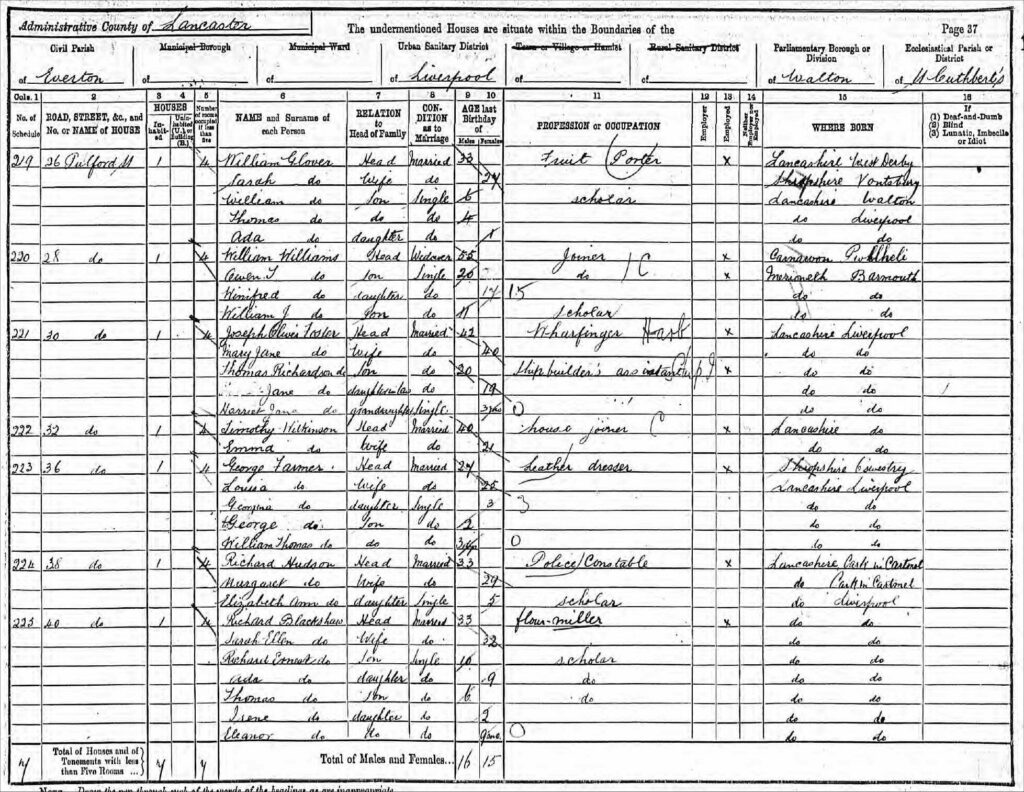

George Farmer started his footballing odyssey with the White Star team of his hometown, Oswestry. Nicknamed ‘The Skinners’, tradesmen of that epithet made up the White Star’s number. George Farmer trained as a skinner and worked as a leather dresser or finisher for much of his adult life, alongside his footballing exploits. In early 1883, the White Star club combined playing resources with Oswestry Football Club, and it was with this team that Farmer first came to Everton’s attention, playing against them in successive fixtures home and away, across a fortnight in March 1883, scoring in a 5-2 win for the home team at Oswestry. The next step for Farmer was a big one; onto the international stage.

A claim has been made in certain quarters that George Farmer’s Wales career ended by default when he came to Everton, with the Welsh Football Association taking the same stance as their Scottish counterparts for a period, namely, refusing to select players for the national team who played for a club outside the boundaries of their home country. This is not the case. In February 1886, Football Association regulations were amended to state that players, amateur or professional, could only represent the country of their birth, although Farmer’s Everton teammate Charlie Parry, also Oswestry-born, would somehow get round this ruling, with the history books often reporting him as having been born across the border in nearby Llansilin. George Farmer was born in Oswestry, Shropshire, to Welsh parents and may well have spoken Welsh, but at this point, genealogy did not come into the equation. Notably, while an Everton player, Farmer was later selected twice as a non-playing reserve by England in 1887, the first Evertonian to be chosen for such an honour. Bob Howarth, then of Preston North End, made his England debut that same year, but did not sign for Everton until 1892, a year or so after Farmer had departed. Johnny Holt became Everton’s first England international in 1890/91 season.

Nonetheless, George Farmer goes down as the first international footballer whose services were engaged by Everton Football Club. Quite a coup for a team still striving hard to establish itself alongside heavyweights like Preston, Bolton. Wolves and the Blackburn clubs. It is unclear exactly when, or indeed if, any formal contract was signed by Farmer or Dobson, or whether exchange of any recompense took place between Everton, Oswestry and Bolton Wanderers respectively at the time, but some form of agreement was reached in late March of 1885 before professionalism was formally legalised in basic terms a few months later. A fortnight earlier, George Farmer made his two appearances for Wales, at Blackburn versus England, and at Wrexham versus Scotland, alongside his future Everton teammate and fellow professional, striker Job Wilding of Wrexham Olympic. Within a year, Wilding would become the first player to play for his country while on Everton’s books, thus dispelling the myth, once and for all, that only Wales-based players were eligible for selection at this time.

George Dobson’s Everton debut came at Anfield on 3 April 1885 against Blackburn Rovers. George Farmer’s bow followed eight days later, alongside Dobson, on 11 April 1885, again at Anfield, versus Crewe. This fixture took place one day short of 100 years before an Everton side managed by Howard Kendall strode out at the Olympic Stadium before 67,000 supporters to earn a 0-0 draw versus German giants Bayern Munich. Little did George Farmer and those nascent Evertonians who made up a crowd of around 3,000 know what foundation stones they were laying that Saturday afternoon at Anfield.

Farmer’s first Everton goals came in the form of a hattrick a week later, in an 8-2 walk in the park in a charity match versus Haydock Temperance. He would finish the 1884/85 season with eight goals from seven appearances. The following season,the Farmer would flourish, netting 35 goals in 43 appearances – an Everton record not beaten until Bertie Freeman notched 38 goals in 38 games in the 1908/1909 season – and helping Everton to ‘the double’ of Liverpool Senior Cup (Job Wilding scored the winner versus Everton’s original local rivals Bootle) and the Liverpool Association Shield (goals from Farmer and Wilding earning a 2-1 extra-time win again versus Bootle).

The 1886/87 season would see Farmer net 26 goals in 47 appearances, as Everton retained the Senior Cup, this time with a 5-0 thrashing of Oakfield Rovers in the final. By now, Farmer had set other goal-scoring record with an eight-goal haul in a 14-0 Senior Cup tie win versus New Ferry, plus five more in a fixture versus a North East Counties XI. Not bad for a player whose principal position throughout this period was nominally in support of the main striker, at inside-left. He also appeared wide on the left of the forward line, dropped back to a wing-half role, and even appeared at full-back on a handful of occasions during his Everton career.

Farmer’s magic was in the way he carried the ball past players on his own, dropping his shoulder and dribbling without fear. He blitzed opposition goalkeepers with long-range efforts, occasionally to the consternation of teammates and reporters who would refer to his propensity to ‘have a go’ at will throughout his career. One report dubbed him ‘the King of the screw shot’, an early interpretation of what modern football fans would understand as ‘bending it like Beckham’. Farmer was renowned as one of the finest early exponents in the game of the in-swinging corner kick. He was a left-footed set-piece specialist, who laid down a template for the likes of Sheedy, Hinchcliffe and Baines to follow in decades to come; an artist in the mould of Alex Young, Duncan McKenzie, Pat Nevin or Anders Limpar, adored by Evertonians everywhere.

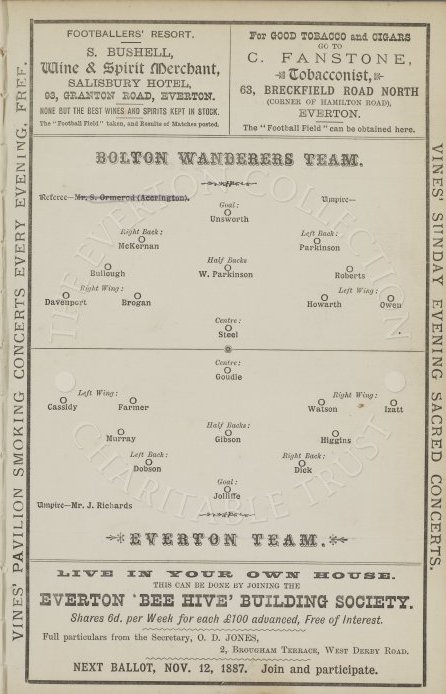

The 1887/88 season saw Farmer’s goal output reduced somewhat to 14 from 41 appearances, and no end of controversy on the pitch as Everton’s first foray into the F.A. Cup took place. A first round defeat against old rivals Bolton Wanderers was scratched from the records, as Wanderers were found to have fielded an ineligible player. Two replayed games ended in draws, Farmer scoring in both, thus becoming the first professional to score a goal in an officially recognised Football Association competition, (after teammate Bob Watson opened Everton’s F.A. Cup account in the first replayed game). A 2-1 win in the fourth match of the series saw an early example of Everton’s wretched luck with cup draws, as they were plucked from the hat to face the might of Preston North End away. A 6-0 defeat followed, but worse was to come, as Everton were found to have fielded umpteen ineligible players against Bolton.

The rules around professionalism were still in their infancy at this point, which goes some way to explaining the ambiguity and transgressions. Everton were banished from the competition, then stripped by the Liverpool Association of their previous season’s Senior Cup title on charges of having brought the Association into disrepute. The Association also removed Everton from the current season’s competition. Sweet revenge for Bootle who were reinstated in their place, after having been knocked out by Everton, Farmer scoring in a 2-0 win at Anfield.

And so, to League football. By now approaching 26 years of age, George Farmer might have hoped to have been entering his prime playing years. That said, he had still held down various manual jobs, including bottle washing at John Houlding’s brewery (possibly as a cover for the fact he was being paid by Houlding in those early months to play for Everton), plying the trade he had learned as a young man; that of a leather dresser, also working as a tinsmith and later as a gas meter manufacturer at the gas works by the old Everton baths at the top of Everton Brow.

Farmer had missed a big match versus local rivals Stanley in March 1886, having suffered an unspecified injury during the week at work. Farmer was also on the unfortunate end of a bizarre pitch invasion in a match in August 1886, when a child’s kite blew onto the ground and tangled between his boots just as he was on the ball, bursting through on goal.

On Christmas Day in 1885, Farmer married Louisa Gallant at Holy Trinity Church on Breck Road, and played later that day at Anfield in a 4-0 win over Irish visitors Ulster FC. He later incurred the wrath of the Everton directors after turning up late for the home match versus Derby County on 17 March 1888, despite the fact the family were living on Lake Street, just yards from the Anfield ground. A likely explanation was that it was the day that George and Louisa’s first child, a daughter called Georgina, was born. Eleven more children would follow over the next 17 years, so making ends meet must have been an enormous challenge. Working long hours during the week as well as playing football for a club desperate to be a part of the inaugural Football League set-up must have taken its toll.

(The Everton Collection)

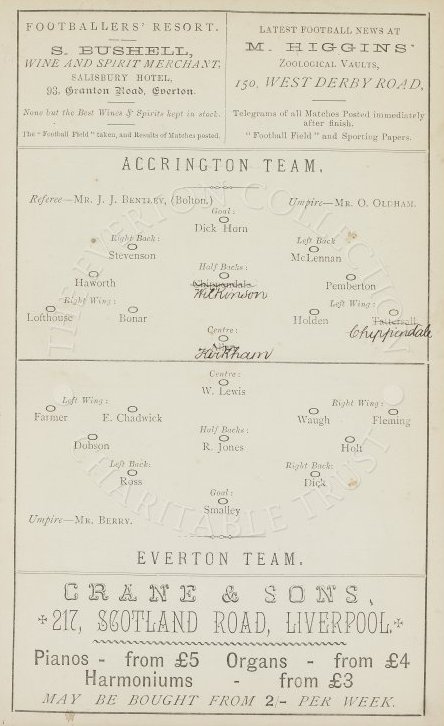

Nevertheless, it was George Farmer’s trusty left foot which created George Fleming’s two goals against Accrington on 8 September 1888 in Everton Football Club’s first ever Football League fixture. Farmer would feature in all bar one of Everton’s games that season, scoring just once, in a 2-0 Anfield win over Aston Villa, and primarily playing much deeper than he had in his early Everton days, as part of a half-back line alongside Lancastrian new boy Johnny Holt and Scotsman James Weir. Farmer would only make ten appearances in the second season of League football, before appearing to fall out with the Everton directors, earning a reprimand from club president John Houlding and ultimately being suspended and banished to the junior teams for several months. Thereafter, he moved to West Manchester, a side pushing to make a name for themselves, in the days before United and City had blossomed from Newton Heath and Ardwick.

After West Manchester folded, Farmer returned to Liverpool, where his family continued to expand at a rapid rate. He played for a season alongside fellow Evertonians Charlie Parry and Dan Kirkwood for Liverpool Caledonians, happily making a sole appearance at Everton’s new Goodison Park, just a fortnight after it opened in August 1892, in a friendly match versus the Everton ‘A’ team. He also made a handful of appearances for Everton Athletic, a primarily amateur club who often fielded several Everton Football Club old boys, including Farmer’s old pals Mike Higgins and Bob Watson.

………………………………………..

Read more about Liverpool Caledonians here

Read more about the Opening of Goodison Park here

………………………………………..

Thereafter, Farmer enjoyed a five-year footballing Indian summer of sorts as captain and mainstay at the heart of the midfield for Liverpool South End, the original footballing standard bearers for the south end of the city at their Shorefields ground in the Dingle, just yards from the Florence Institute. By now in his early 30s, the veteran Farmer guided South End to the Liverpool and District League title in 1895, and promotion to the Lancashire League. Bolstered by the addition of ex-Everton goalkeeper David Jardine and ex-Everton and Liverpool forward Paddy Gordon, as well as James ‘Punch’ McEwan (who would go on to become a member of the backroom staff behind Herbert Chapman’s all-conquering Arsenal side) South End shone briefly, before ultimately combusting, as so many promising clubs did in that era. They were later succeeded by the club which became South Liverpool Football Club. Farmer and several of his South End teammates would cross the Mersey to play for Rock Ferry for a period, but few records survive, other than Farmer smashing home two trademark goals in a game against Stoke.

By 1905, the Farmer household consisted of seven children between the ages of 17 and two. Four more had died in infancy. George’s parents back in Oswestry were both long dead, with tuberculosis having accounted for his father and at least two of his siblings. Louisa lost her mother in February 1905, and her 75-year-old father William, a Master Mariner, would be married for the third time within a few months, to a woman 24 years his junior, and live to 91, a remarkable age at the time. Throughout this period, Louisa was heavily pregnant, and George was gravely ill.

As a boy, George Farmer’s family were among the early migrants to a new-build estate in Oswestry called Castlefields. The industrial revolution was in full swing when George was born on 13 December 1862 at the family home, a small cottage at Queen’s Head Yard in the town centre, while the town was expanding quickly. Alas, Castlefields had been constructed on damp, boggy ground and the area soon became known locally as the ‘Dismal Swamp’. Living in such conditions, tuberculosis, rheumatic fever and other respiratory diseases were rife, particularly amongst children, and it is highly likely that George would have suffered from something along these lines. His cause of death, which occurred on 4 May 1905 at the family home of 123 Belmont Street in Everton, was pericarditis, or damage to the lining of the heart, almost certainly caused by a childhood bout of rheumatic fever or similar.

Distraught, and just days after George’s funeral at Anfield Cemetery, Louisa gave birth to her twelfth child, a baby boy she called Arthur, on 19 May 1905, two weeks to the day after George died. Alas, baby Arthur would also pass away just a year or so later.

The local community rallied around the Farmer family quickly. When George had first arrived in Liverpool to play for Everton twenty years previously, he had lodged with the Holt family at 1 Gertrude Road in Anfield, less than five minutes’ walk from the football ground. Two decades later, and it would be the Holt family who would come to Louisa Farmer’s aid, coordinating a public subscription. Think ‘JustGiving’ today – with the aid of appeals in the local press, plus an initial donation of £10 from Everton Football Club, much needed urgent assistance was quickly provided. On 27 May 1905, a gathering of well-wishers was held at the Sandon Hotel, coordinated by individuals including George Dobson, early Everton great Jack McGill, and Alex Nisbet, who had served as club secretary-manager during Farmer’s Everton playing days, and Matt McQueen, a former Liverpool player and future title-winning manager at Anfield.

A ‘Benefit Fund Committee’ was established by the Everton directors, and the gate receipts from an Everton reserve team match versus Stockport County reserves in October 1905, was set aside for the family. Legendary future Everton trainer Harry Cooke played for Everton in this fixture, a 3-2 win for the Everton side, and £33. 5s. 8d. was raised. This, combined with Everton’s original £10 donation, would be the equivalent of around £6,000 in modern terms.

With the money, Louisa invested in number 36 Oakfield Road, from where she ran a tobacconist’s shop. Everton’s directors had suggested placing the money in a bank account, with a weekly allowance available to Louisa, but, showing characteristic grit and determination, she stood firm and demanded the full amount as a lump sum. Within a few years she had sold the business, and found work as a stewardess on the White Star Line out of Liverpool. George might have smiled at the idea of his wife joining the White Star Line all those years after he made his name with the White Stars football team in Oswestry. She served at one point on the ill-fated Lusitania, and was scheduled to travel to Southampton to serve aboard the Titanic, only to receive last-minute orders to stand down. At the outbreak of the Great War, Louisa was working aboard the Arabic when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Fortunately, she was among the survivors, and returned home, where her and son Edward established successful fish and chip shops in Liverpool and Heswall. A watch from Louisa’s service with the White Star Line is still in the possession of one of her great granddaughters in Liverpool.

Of the seven Farmer children who survived to adulthood, six of them raised families of their own, descendants of whom continue to thrive today. Eldest son, George junior, and his wife relocated to Adelaide, Australia in 1922. On their marriage certificate from 1914, George junior lists his father as ‘George Farmer, Professional Footballer’, possibly the only surviving official document alongside the birth certificate of daughter Eva, where this information is detailed, as even the players of those early days appear themselves perhaps to have struggled to acknowledge playing football as a genuine occupation. Most tended to list their practical trade as their occupation in census returns and civil documentation. A certain stigma surrounded professionalism for a long period after it was formally legalised, and it cannot have been easy for the early professionals, who must have been subject to jealousy in some quarters, as well as higher expectations from impatient fans and directors. Remarkably, two grandchildren of George and Louisa are still alive today in 2024, and George Farmer’s belt, complete with ‘EFC’ buckle, standard issue for Everton players in the 1880s, exists in fine condition with a great-grandson in Heswall, whose daughter was a founder player with the Chester City women’s team.

Football is all about hopes and dreams, and we all recall the first time we squeezed through the turnstile at Goodison, walked up the steps and looked out on that vast expanse of green before us. When the time came for the formation of the Football League in 1888, Everton were still not rated as quite on a par with the top clubs of the day. They had to fight their corner to be accepted as one of the twelve founder member clubs, and it could legitimately be argued that they achieved this, at least to an extent, off the back of their burgeoning popularity with supporters. Few clubs could match the size and raucous nature of the crowds that Everton were drawing, and this recognition by the paying public was inspired directly by the skill, dash and derring-do of players like George Farmer. The club had taken regular heavy beatings by the likes of Bolton and Preston in particular, on their gradual ascent to the level of luring and employing professional talent. They looked to Bolton’s example of expansive football, and it was Farmer who led the charge with his close-control, flamboyant dribbling and sharp crossing and shooting with that rapier-like left foot.

Supporter testimony from the era, points to Farmer as the leading light in the progress of the Everton team, and consequentially, the development of the club as a genuine force in football, in those crucial years directly before League football was established. The outpouring of sympathy and support when Farmer died, fifteen years after he had kicked his last ball in anger in Everton colours, is testament to the high esteem in which he was held by both Evertonians and the football club itself. Now, in 2024, with Everton about to depart Walton after over 140-years’ residence, for pastures new at the Everton Stadium on the waterfront, it is fitting that one last push be made to mark George Farmer’s legacy as one of the key protagonists and foremost pioneers in the foundation of Everton as a truly great football club.

………………………………..