Rob Sawyer

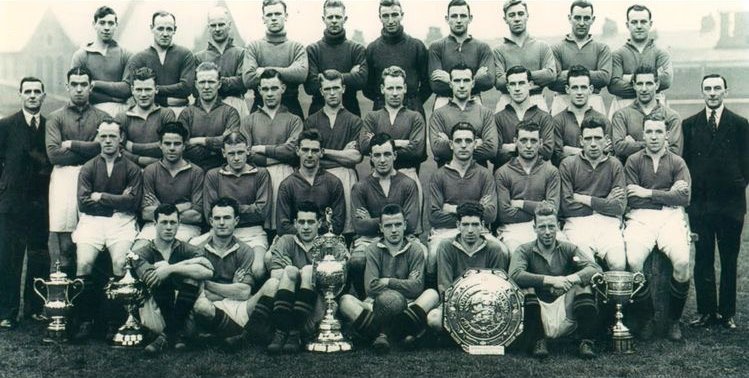

Tommy Johnson’s most memorable goalscoring feat may have come as a Manchester City player at Goodison Park but he would go on to help Everton back into the top flight in 1931 and lift both the title and FA Cup in successive years.

…………………………….

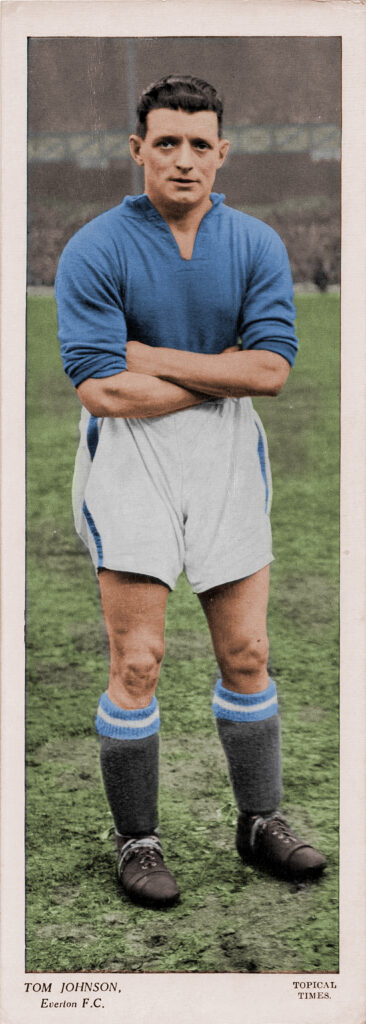

In September 1928, Tommy Johnson achieved one of the finest scoring feats accomplished at Goodison Park. Sadly for Toffees supporters, his spectacular five-goal haul was achieved two years before he swapped the sky blue of Manchester City for the royal blue of Everton. Once he did make the move to Goodison, ‘Tosh’ – an inside-forward with an eye for goal and a killer pass – enjoyed a trophy-laden four-year spell.

Thomas Clark Fisher Johnson (the two middle names were taken from his grandparents’ surnames) was born on 19 August 1901 in Dalton-in Furness, four miles from Barrow. He grew up with his parents John and Margaret until a seismic change occurred when he was only nine years old. His parents, seeking a better life, took the momentous decision to join John’s relatives living in Utah, USA. Crossing the Atlantic for a new life were John, Margaret (pregnant at this time) and their daughter Eleanor – but no Tommy. He was settled in a good school – his sporting capabilities had earned him a scholarship – so his parents had taken the agonising decision to leave him in the care of his grandparents in Dalton. They would come back to visit a couple of times and Tommy would get to meet his new baby sister, Elizabeth. John died in 1915; Margaret would subsequently remarry and remain in Utah. It says something for Tommy’s mental strength that he coped with these early life upheavals.

Growing up on Queen Street, Dalton (where Johnnie Baxter, a Rugby League star for Rochdale Hornets, England and Great Britain, had also lived there), Tommy attended Broughton Road Council School. Having first excelled at Rugby, he was soon dribbling a cheap football around all-comers in the sloping school yard. He joined Dalton Athletic FC before switching to Dalton Casuals FC, all the while doing his apprenticeship as a riveter at the Barrow shipyard. At 17, playing for the Casuals in the wartime Munitions League as a centre-forward, he attracted the attention of football clubs from outside of the immediate area. In February 1919 Manchester City invited him for a trial as an amateur. He discussed it with his schoolmaster, who advised against risking his shipyard apprenticeship – but his schoolmaster recounted later that the teenager exuded tremendous confidence and grasped the chance to go to Manchester wholeheartedly.

City full-back and captain, Eli Fletcher was immediately impressed with the Dalton lad (who was initially accommodated at the Midland Hotel) and strongly urged his club to tie him to a professional contract. Team manager Ernest Mangnall agreed, and Tommy was a professional footballer within a month of his arrival in the Lancastrian city. He was soon rechristened ‘Tosh’ to differentiate him from several players named Tommy, already at the club.

The newcomer debuted in the wartime Football League Lancashire Section, scoring one in a defeat of Blackburn Rovers. His Football League bow came in February 1920, and it could hardly have gone better as he scored a brace against Middlesbrough. In only his sixth appearance, a home match against Liverpool, he was introduced to King George V before kick-off. It took until the autumn of 1922, however, for him to be established as a regular starter. He lined up in the inaugural competitive match at Maine Road at the start of the 1923/24 season, in the wake of the club relocating from Hyde Road in Ardwick). Horace Barrel would score City’s first goal in the place they’d call home for 80 years – but Tommy would notch the crucial second in a 2-1 victory over Sheffield United, a proud moment for the Dalton man. In the FA Cup that season, City progressed to the semi-final before coming up short against Newcastle United; it would be the great Billy Meredith’s last match, at the grand age of forty-nine.

Later that year, Tommy married Manchester girl Hannah ‘Annie’ Smith. They set up home in Clowes Street and subsequently lived on Park Avenue, Gorton – not far from Manchester City’s present home at the Etihad Stadium. It was a home they would keep for the rest of their lives – just renting it out during periods of absence. Their only child, Alan, was born in 1925. He would recount the following tale in 2017; ‘When I was a baby, one or two years old, on a Sunday morning Mum would get me dressed and dad would wheel me [in the pram] out to the right up Hyde Road. There would be ten blokes following – like an escort there and back. They all used to go to the Plough pub on Hyde Road – but there were three pubs between Park Ave and the Plough – they’d go in all three, one after the other. They’d go in the vault and check occasionally if I was still asleep outside.’

In the 1925/26 season, Tommy claimed his first club hat-trick and broke the 20 goals in a season barrier – something he’d achieve at City three more times. The Mancunians also reached the FA Cup final that season, meeting Lancashire rivals Bolton Wanderers. Young Alan Johnson was there – just turning one – accompanied by his auntie and uncle. Tommy and teammates would (again) shake hands with King George V before kick-off in front of a 91,400 crowd. The only goal of the game was scored by the Trotters with 14 minutes left. Back home, the losing finalists were given a civic reception at Manchester Town Hall before preparing for a vital midweek fixture against Leeds. They won, with Tommy scoring – but a defeat at Newcastle the following Saturday saw the club relegated to the Second Division.

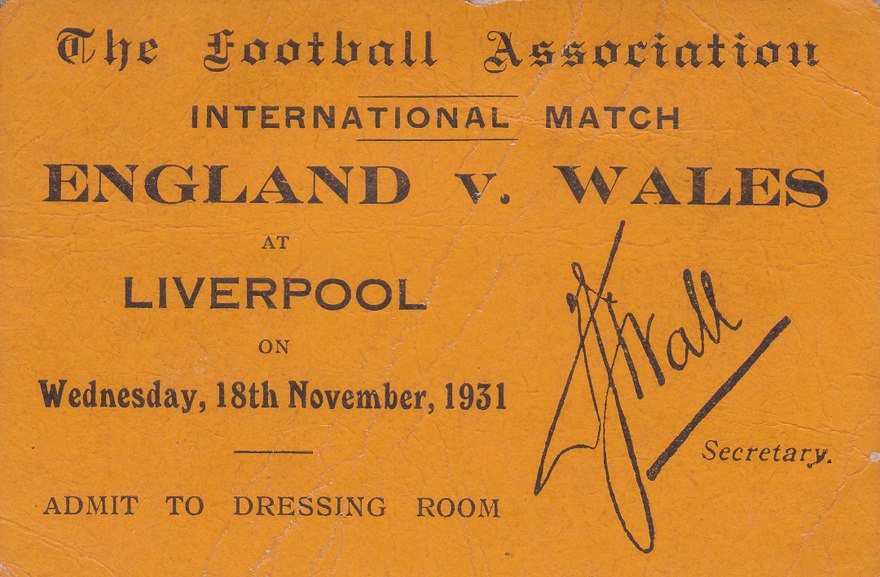

A small consolation for this crushing disappointment was an international call up for Tommy. At 24 he became the 504th player to be capped by England. He duly scored on his debut in a high-scoring match (a 5-3 win for the visitors) at Belgium’s Olympisch Stadion in Antwerp. Nonetheless, he had to wait over three years for his next selection. He promptly scored two more – this time against Wales.

Alan Johnson recalled his father’s devotion to keeping fit, especially after a close season break: ‘At the end of the season we used to go to Dalton, where we had family, and Blackpool, where we had friends. We had three weeks at each. He was so conscientious that in the last week before he used to report back for pre-season, he used to travel by train to Belle Vue and run round the speedway track three or four times with a rubber tyre around his waist.’

Having helped Maine Road denizens back to the First Division as champions in 1927/28, scoring 19 League goals, Tommy would enjoy a career highlight at Goodison on 15 September 1928 – but the match very nearly didn’t happen. The City travelling party assembled at Manchester Central Railway Station (later repurposed as GMEX) in good time to catch a train to Merseyside. However the service ran late – with the players getting changed into their kit on board the train to try to recoup some lost time. Things got worse when the taxis that had been hailed from central Liverpool to take them to Goodison Park became stuck in the throng of match-goers. With the taxis abandoned, the final few hundred yards were made on foot with the players pushing the kit skip up Goodison Road. The ill-prepared Mancunians ran directly onto the pitch nine-minutes late for kick-off and received an ovation from the home crowd – and even a burst of trumpet fanfare from the so-called Goodison Bugler.

The Football League champions, with the sun on their backs, attacked City and scored within the first minute from Tony Weldon. Maybe this was the wake-up call the tardy travellers needed. Switched for the match from inside-left to centre-forward – with Marshall and Tilson in support – Tommy equalised on 26 minutes when running through the middle to finish past Davies. The players exited the field for the break with the scores equal – little could anyone envisage the final score. The second period got underway in bizarre circumstances with the referee Haworth promptly dropping to the ground with a muscle injury. He was bandaged up and returned to officiate the remaining 45 minutes. What followed was the Tosh Johnson Show. He scored his second from the penalty spot and slotted a further three to end on five. Brook added a sixth goal for City with Jimmy Dunn making the sole reply from Everton. The final score at a stunned Goodison: Everton 2 – Manchester City 6.

City were later fined by the authorities for their late arrival at the stadium. As for Tommy, that memorable afternoon set the tone for a record-breaking season as he scored 38 goals in 39 Football League appearances – a club record that stood until Erling Haaland hit 52 in 2022/23. In later years, when asked about this scoring feat by fans, reporters or drinking buddies in the pub, he’d say that the record was not his but the team’s and the honour should be shared: ‘They all helped me to score, I only finished it’ was his stock response.

Just over a year later Tommy starred in a 3-1 derby defeat of their Manchester rivals but was robbed of a wonderful solo effort when the referee blew the whistle, milliseconds before the ball rolled across the line. Galling enough for ‘Tosh’ – but more so when it came to light that the match official had blown his whistle two minutes early. To the shock of Mancunians of a Blue persuasion, their scoring talisman was gone within five months of that infamous refereeing blunder.

The five-goal salvo back in September 1928 had left an indelible mark on the Everton directorate. With the team struggling for goals in a troubled 1929/30 season, Tommy’s name was high on the list of potential recruits. The story of the Toffees’ interest was broken in the Liverpool Post and Mercury on 4 March, but Everton had already been rebuffed in the previous October (Huddersfield Town had been another club making approaches). Now that City were out of the FA Cup, and out of contention for the League title, their officials were more favourably inclined to striking a £6,250 deal. The Merseyside press would report that, at this time, Tommy had been receiving some barracking from sections of the Maine Road terraces, which was, along with Tommy’s age, a factor in the City directors’ willingness to sell. The one person who was unaware of the boardroom negotiations was the player. He was stunned when the news broke in the press and he was approached by similarly bemused supporters. Reluctant though he was to leave his beloved club, he accepted that the decision had been made for him. Some compensation was that he’d be linking up with Dixie Dean, with whom he had got on splendidly on England duty. The next day he was driven by Manchester City officials to Goodison Park to complete the formalities of the transfer.

Tommy left City having scored 158 League goals – a club record shared with Eric Brook until it was finally broken by Sergio Aguero. Although a vocal minority may have been barracking Tommy that season, other City fans wrote to local newspapers to bemoan the transfer and many voted with their feet. Approximately 7,000 was shaved off the average Maine Road attendance figure in the wake of the shock departure.

On completion of the transfer, Bee (Ernest Edwards) of the Liverpool Echo reported on why Tommy had been identified as the man to help fire the Toffees out of the relegation mire:

‘Everton realise that there is need for a key man who shall be not only a general key man but a shot who will not hesitate to let his leg fly when any chance is available. The Everton team is lacking at the moment in what one might call “a snapshot”. All along the line, the forwards chosen are rather too deliberate towards shooting, and each is inclined to move the ball a foot before shooting, which means that the defence often covers them up.’

The same journalist, several years later, would give this updated assessment: ‘Johnson…belongs rather to the brainy school. A man who can hold the ball, steady his co-forwards, distribute the play, and, particularly in the days now gone, send his winged messenger the ball, hurtling through space and on into the net.’

Tommy to the right of Dixie Dean, centre

He lined up at inside-left for his new club in an away fixture at St James’ Park. Although it was noted of the new man that he ‘did some powerful work and created centre-forward passes that were models’, the team played poorly – falling to a 1-0 defeat. It prefaced four defeats on the bounce – even though Tosh was on the mark in three of them. Although Everton rallied with four wins and a defeat in the final five fixtures of the season it was too little, too late. The club was relegated for the first time in its history.

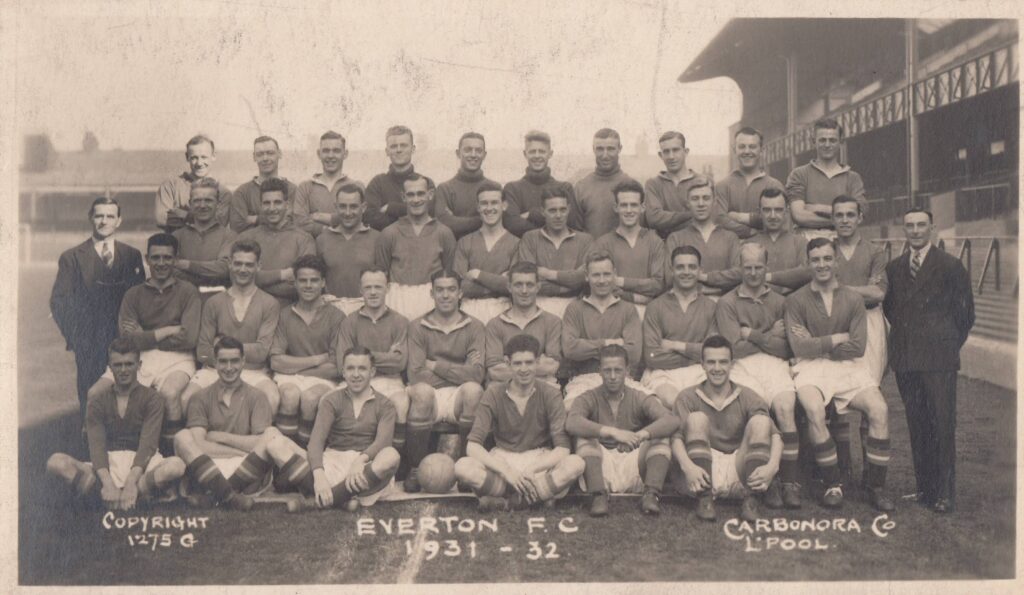

Fortunately, the Toffees demonstrated great ‘bouncebackability’ the following season and Tommy developed into an ideal foil to the fit-again Dixie Dean. The Birkenhead-born striker would score 39 league goals with Tommy chipping in with 14. Although now in his 30s and stockier than he’d been in his City pomp, Tosh was an astute player, able to use a combination of physique, skill and intelligence to lay on chances with his magical left foot for teammates or to strike for goal himself. Andy Cunningham, writing for the Topical Times praised Tommy’s contribution to the Toffees team: ‘Everton were a marvellous attacking combination. Their forward line was a fast-moving set and much of their effectiveness was due to the play of Tommy Johnson. Tommy was adept as the cross-pass to the far wing, and Geldard used to delight in the long raking balls which Johnson threw over to him.’

Better was to come in the following season when the freshly promoted Blues stormed to the League title. Tommy missed just one game – contributing 22 League goals while Dean led the line superbly and put away 45. Tosh was rewarded with three more international caps in this period of his career- bringing his tally to five (scoring five goals). His final match in an England shirt came in October 1932, a defeat of Ireland.

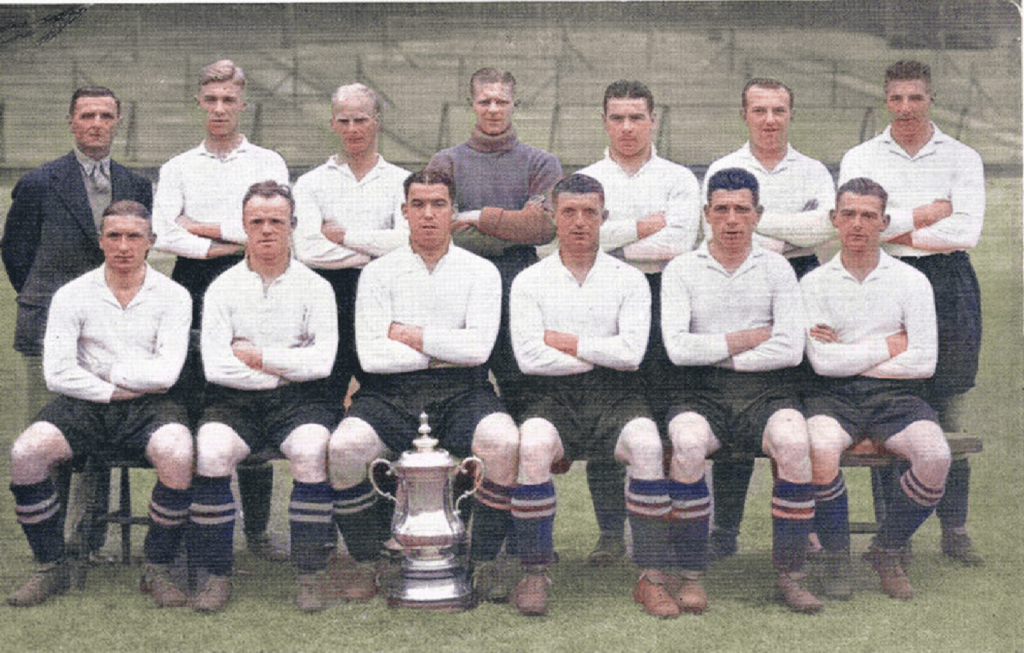

Although the following 1932/33 season brought only a mid-table finish for the Blues, there was cup glory to savour. Everton has beaten West Ham in the semi-final to secure a date at Wembley against, of all clubs, Manchester City. Tommy’s seven-year-old-son, Alan, travelled down with relatives to the match. He recalled: ‘We went down to the game on the train and it was full of Manchester City fans, although my dad was playing for Everton. They were all ribbing me but it was all good-natured!’ The match itself was a fairly routine win in which Tommy – wearing number 10 for the first time – had a steady match without getting on the score sheet or grabbing the headlines.

After the lap of honour and getting changed the Everton team was ready to leave the stadium – and Alan Johnson was itching to congratulate his dad:

‘At the end of the match my uncle carried me to the players’ entrance and we stood facing the door. There used to be a horseshoe shaped little road just big enough for a coach to go round. So, up came the coach – it was the old-fashioned type with the driver on the right – with a policeman at the side. My uncle said to the policeman: ‘Watch him – don’t let him get hurt.’ Dixie got on first and sat at the front with the cup, with Ted Sagar and my dad sitting behind him. They wound the window down and the policeman lifted me up. All of a sudden two hands grabbed me – then two more. Ted and my dad then pulled me through the window into the coach and sat me down at the front with Dixie Dean. So I was on the coach holding the cup all the way through London!’

That wasn’t the end of Alan’s memorable experiences that weekend: ‘When they were waiting at Euston to get the train back on the Monday morning. I met my dad and Dixie, and we were walking through the station. Then Dixie grabbed me, and we walked up to the train carrying the cup between us.’

(colourised by George Chilvers)

Just four days later the Blues were back in action against Sheffield Wednesday at Goodison Park. Suffice to say that certain members of the squad were still toasting their success several days after the final. Alan Johnson recalled how Dixie Dean needed a helping hand from his teammate: ‘There were a few steps [from the tunnel] up to the pitch. When Dad got to the ground and got changed Dixie said, “Hey Tommy – give me a push when I get to the top.” Dad said “Why?” and Dixie replied, “I am still drunk and I want to run onto the pitch!” They lived life and enjoyed it.’ Tosh didn’t forget his roots and shortly after the Cup triumph he sent a football signed by the Everton squad to be auctioned off by Barrow FC in aid of one of their former players.

A straightforward character, Tommy was a popular member of the Blues squad and developed a strong friendship with Dean. Alan Johnson recalled Dixie’s frequent appearances in east Manchester: ‘Dixie Dean used to come to our house if they had played in Manchester or in Sheffield. He’d stay in the house overnight in the spare bedroom. Mum would do potato hash and then, at 7pm they’d walk up Hyde Road and have a drink in each pub – four or five – until they got to the Plough where they’d sit in the vault talking to the regulars.’ Naturally, there would be no shortage of people asking Tommy about the forthcoming match and offering to stand him a drink (he’d happily accept a pint of best bitter).

Of Dixie’s ability on the pitch, Tosh was fulsome in his praise. On his strike-partner’s 60th birthday he paid this tribute: ‘Billy used to play with chipped ankle bones and all sorts of injuries. But if Billy said he was fit that was it. It was his great ability to head the ball with power and precision that scored and set up so many goals. He used to hang so long in the air I often thought he would never come down; it was a gift he exploited to the full.’

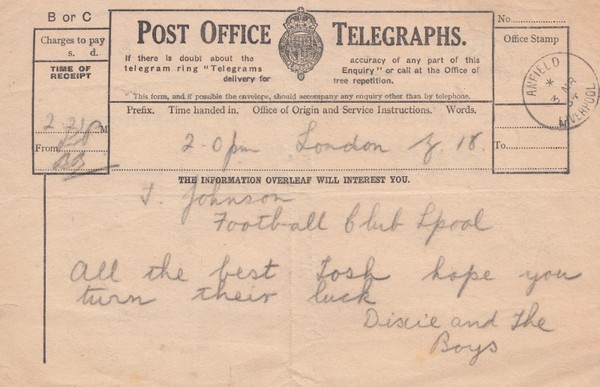

In March 1934 Everton’s ‘available for transfer’ list of eight senior players was leaked to the press. Tommy’s name was on it. Within a day the 33-year-old was crossing the great divide and signing for Liverpool for £650. He left Everton having scored 65 goals in 160 appearances, but mere statistics do not give lie to his positive influence on a club that he joined in dire straits. He left on good terms – with an accrued benefit (long service) cheque for £468. As he prepared for his Anfield debut against Middlesbrough a telegram made the short journey across Stanley Park, addressed to the new Liverpool forward: ‘All the best Tosh. Hope you turn their luck. From Dixie and the boys.’

Tommy certainly did help to improve the Reds’ fortunes – in 11 appearances that season his experience helped steer the club away from the relegation zone. He was used sparingly in the subsequent two seasons, clocking up a further 28 outings before being released in the summer of 1936. He was promptly engaged as player-coach at Darwen FC of the Lancashire Combination, a post he held for one season.

In 1940, with the war going badly for Britain, Tosh volunteered for the Royal Artillery. He was made a corporal and sent to an anti-aircraft battery in Scotland. Allan, meanwhile, was serving in the Royal Navy on a minesweeper. In July 1941, Tommy wrote to Merseyside sports reporter Don Kendall (known as Pilot) – the letter was published in the Liverpool Evening Express: ‘I have lost the superfluous flesh and, believe it or not, I am still playing football and doing my stuff. I am fitter now than I have been for some years, and it would do Harry Cooke and Charlie Wilson a world of good to see me.’ Tosh finished the letter by sending his warm wishes to Everton and Liverpool supporters. Not long after he was posted to Scotland, Tosh had to return home on compassionate grounds as Annie was ill. In the end he spent only six months of his service away from Gorton.

Tommy followed the well-trodden veteran footballer’s path to the pub trade. Family recollections suggest that he had a hand in running a pub in Rhyl that was in the extended family – possibly shortly after he’d been convalescing from Tuberculosis in the area. However, it was closer to home that he established himself as a publican – the majority of his career in the trade being as mine host at The Crown on Clowes Street, Gorton. The pub was popular – boosted by footballers past and present calling in for a pint. On one occasion Bert Trautmann, newly signed for City in 1949, came in for a drink but was cold-shouldered by the patrons, on account of his history as a PoW. Annie, seeing this, took matters in her own hands – coming out from the bar, introducing herself, shaking the goalkeeper’s hand and telling him to make himself at home there. The others in the pub took the prompt and got chatting to the young German. When interviewed at his pub in 1954, Tommy was asked to give words of advice to young players. His message was simple: ‘If football is your job of work, then you must put all you have into it.’

Tommy enjoyed a football final curtain call when Everton veterans took on their Liverpool counterparts in a charity match staged at South Liverpool FC early in 1950. Alan Johnson recalled: ‘My dad had played for both. So who would he play for? Well, he’d played for Everton more, so he played for them. They got changed – they all had their bellies [by then]. Deany scored and walked off the pitch. He said: “I have done my bit”. He got changed and dressed and they are all cheering. Dad said, “Where’s Deany?” He was in the social club behind the ground.’

The one-time hero of the Maine Road terraces would still find time to regularly watch his first footballing love, in spite of his happy and successful years on Merseyside (he would always tell his son that he City to thank for the good life he had there). He was particularly thrilled when his former Everton clubmate, Joe Mercer, led City to dizzying heights in the late 1960s. He was reunited with his 1933 Cup-winning teammates in 1966, when they were invited guests of Everton for that year’s FA Cup Final and the subsequent banquet.

In January 1969, Tosh, Joe Mercer and Dixie Dean were guests at a function in Knutsford to launch a range of Texaco ‘famous footballer’ medals. The ex-Toffees trio were in sparkling form when asked to compare the football of the late 1960’s with their heyday. Expressing frustration at the lack of attacking intent in modern football, Tommy said: ‘You watch some teams working the ball nicely out of defence. But when the build-up reaches the 18-yard line – and you’re expecting a shot – you see the goalkeeper picking the ball up again at the other end. They’re all playing it back, and no one seems ready to have a go at goal.’ Dixie then chipped in: ‘When I watch the wonderful Everton team playing, it can affect me like George Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue. But with some of the other teams it’s like hearing the first couple of lines Colonel Bogey.’ As for Joe, he put down the lack of goals in 1960s football to there not being players of the calibre of Dixie Dean.

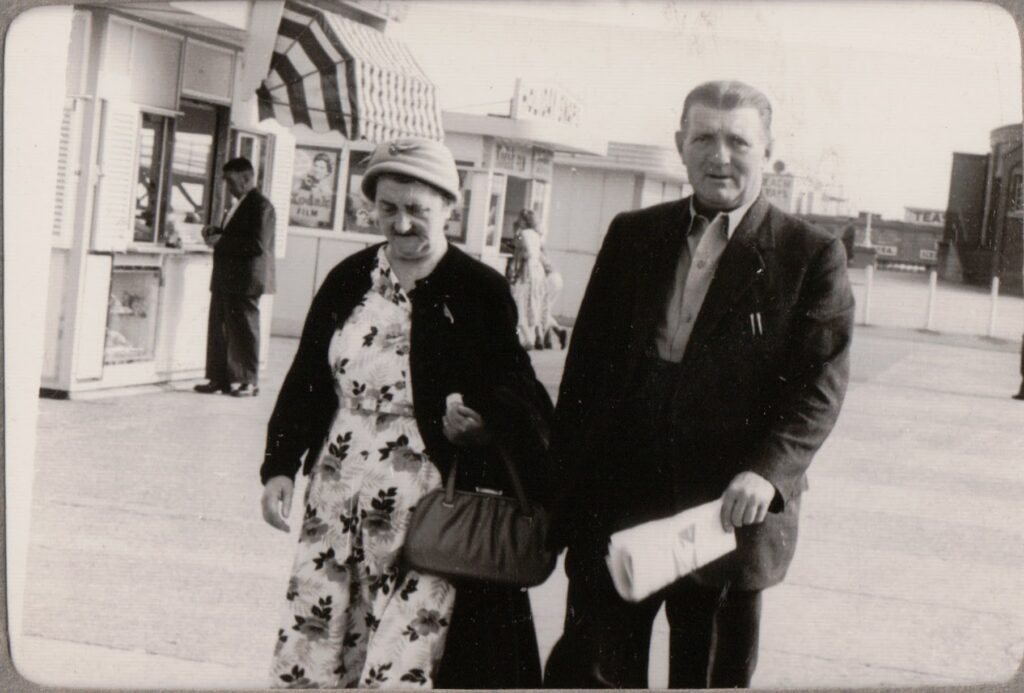

Tosh would become a doting grandfather to Alan’s two daughters, Alison and Joanne. The former retained many fond memories: ’What a wonderful man he was – a cuddly granddad. He was very kind and generous, always with a twinkle in his eye. I really wish that I had taken the opportunity to talk with him about his football more. On Sundays he’d come to our house. He always brought magazines for my sister and I and we’d sit on the floor reading them. He’d sit in the dining room with my dad and spread the newspapers out on the table. They’d talk about the previous day’s matches – and then he’d walk to the friendship pub on Hyde Road for a couple of pints where he’d see friends and other old players. Then he’d tootle back home to grandma for the evening meal.’

Alison never recalled her grandfather being ill but Annie was sickly, so Tommy would often be seen out and about in Gorton with the wicker basket doing the errands. In the winter of 1972-73, Annie was hospitalised for a while, so Tommy would make frequent visits to the ward. He didn’t drive so it would involve long walks in the rain and cold. A chill got onto his chest and developed into pneumonia – the earlier bout of TB would have been a contributory factor. Tosh was admitted to Monsall Hospital but did not recover and passed away there on 28 January 1973; he was 72.

Four years after his passing, Tommy joined a select band of footballers to have had a street named in their honour. Tommy Johnson Walk is in Moss Side, along with the adjacent Fred Tilson Close, Sammy Cookson Close, Sam Cowan Close and Horace Barnes Close. They are situated less than half a mile from the site of Maine Road. He was also one of the first 15 inductees into the Manchester City Hall of Fame in 2004 (he was selected for the period 1911-1927); his son Alan collected the award. Speaking of his father to a Cumbrian newspaper in 2002, Alan said: ‘I am extremely proud. My father was an all-time hero.’ Over on Merseyside, Tosh was an early inductee into Gwladys Street’s Hall of Fame but has not, to date, been awarded the status of Everton Giant – an honour bestowed on his teammates Dixie Dean and Ted Sagar. Maybe his time will come.

Author’s note:

This article is dedicated to the memory of Alison Kempster, who passed away in 2022. Without her help and that of her sister, Joanne, it would have not been possible to write it.

Acknowledgements

The Johnson family

Pat and Thomas Shaw.

Sources:

Alan Johnson plus his daughters recorded in conversation with Bernard Halford and Stephanie Alder at Manchester City in 2017

Gary James, The Official Manchester City Hall of Fame

Ian Penney, The City Alphabet

Steve Johnson, Everton – The Official Complete Record

Chris Goodwin, England Footballers Online (www.englandfootballonline.com)

James Corbett, The Everton Encyclopedia

David France with David Prentice, Gwladys Street’s Blue Book

Billy Smith, Blue Correspondent website newspaper transcriptions (bluecorrespondent.co.uk)

Various regional newspapers including the Liverpool Echo and Evening Express

Images used are from the Johnson family collection.