By Rob Sawyer

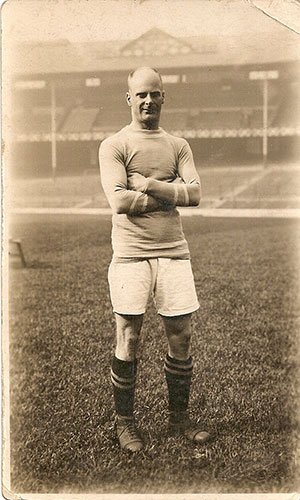

The retirement of Leighton Baines in 2020 reignited the debate about who has been Everton’s finest left-back. Unsurprisingly, the Kirkby-born England international was in the mix, along with World Cup hero Ray Wilson and the combative but effective Pat Van Den Hauwe. A natural tendency to favour players we have seen with our own eyes makes ranking players spanning many decades fraught with difficulty. The tactical evolution of the sport is a further complication. The modern breed of full-backs play an important role in attacking movements whereas the likes of Billy Balmer and Billy Cook in the 1900s and 1930s were top class defenders but were not often required to cross the half-way line. Like Balmer and Cook, Warney Creswell spent his career seamlessly interchanging between right and left-back positions. This cerebral, balding, defender, who played for Everton into his thirty-nineth year, garnered the title the Prince of Full Backs and merits his place in the pantheon of great ‘number threes’.

Warneford ‘Warney’ Cresswell entered the world on Guy Fawkes Night 1897. Although born and raised in South Shields, his roots lay elsewhere. The Cresswell name hailed from Somerset, whilst Warneford (sometimes spelt Warnerford and variations, thereof) was the surname of Warney’s great-great-great grandmother; in time being passed down the line as a Christian name. Warney’s grandfather, Charles Warnerford Cresswell, was raised in Creech St Michael, but emigrated with his wife to Victoria, Australia in the mid-1850s. Their second child, Warnerford (known as George), was born there in 1857, but by 1890 he had left his siblings and parents and headed to the motherland (some census returns failed to mention Warnerford’s Antipodean birthplace). A marine engineer by trade, he settled in the seafaring and shipbuilding heartland of North East England, marrying local girl Charlotte Clayton in 1890. The newlyweds went on to have six children (the first, Winifred, dying in infancy). Warneford Jr. (known as Warney) was the fourth.

Young Warney learned all about football in improvised games in a nearby back lane, using a ‘football’ consisting of rolling up newspapers bound together by string. Even at this early age he reduced his teammates to watching in awe as he switched the ‘ball’ speedily yet effortlessly from foot to foot (maybe the origins of his ease in using either foot during his professional career). A painfully shy child, he found it difficult to cope with the adulation his ball skills garnered. Warney attended Stanhope Road School and by the age of 10 he was turning out with 14 years-olds in the school team. In this period, he was playing as a wing-half, the position in which he represented Durham County Schoolboys and England Schoolboys at the age of 14.

Boys like Warney, with a quiet and unassuming manner, can attract the unwanted attention of bullies, but the aggressors can misjudge the fortitude of their targets. One such playground pugilist swaggered across the school yard towards Warney, breaking into a gallop. Warney stood still until the wannabe persecutor came within arm’s reach – and then floored him with a swing of his right fist. As Warney walked away from the scene, still trembling with a mixture of fear and adrenaline, the bully lay ‘spark out’ on the ground. He wasn’t troubled by bullies again.

Next was Westoe Secondary School. Here the teenager excelled at cricket and the games master urged him to consider it as his sporting profession – however, his heart was set on soccer. Ironically, in light of what he’d go on to achieve in his football career, his most-prized medal was the one he won for becoming school sports champion at the second attempt. Having been pipped by George McIntire (who entered more events), Warney came back even more determined at the next school sports day. After a period of fanatical training and preparation, he won the 100 and 220-yard sprints and high-jump competition to land the overall title of champion.

Come 1914, he surprised observers by turning down his hometown football club to join North Shields, across the river, as the latter offered the better prospects of first team appearances. He was also on the path to becoming a teacher as his main career. With the outbreak of war, Warney enlisted and was posted to the Royal Artillery camp near Edinburgh. Word of his displays in army football soon reached the ears of Hearts, who promptly persuaded him to turn out against a team that Warney had great affection for: Greenock Morton. Coming up against many ‘names’ that he admired, Warney had a poor match (in his mind – Hearts thought otherwise). Beating himself up about it, he was changed and out of the dressing room within 10 minutes of the full-time whistle – vowing not to play for Hearts again, in spite of their repeated pleas. Instead, he turned out for Edinburgh side St. Bernard. Later in the war, when posted in southern England, he appeared for Tottenham Hotspur.

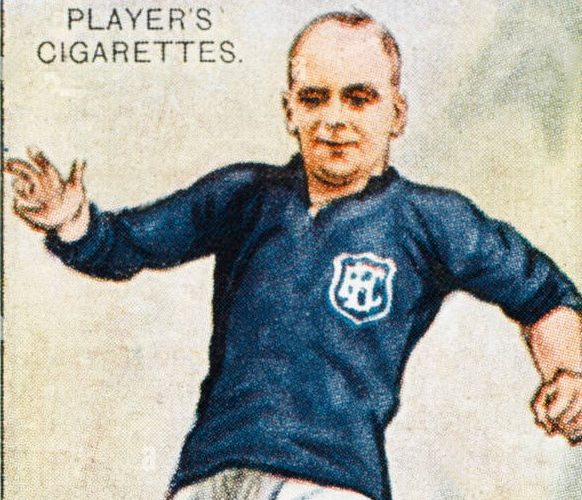

Come the end of the war, several professional clubs (Hearts among them) beat the path to the family home at Stanhope Road, but it was for South Shields – then of the second tier – that Warney belatedly signed. In his three seasons at Horsley Hill, playing under manager Jack Tinn, Warney earned his first full England Cap (against Wales in March 1921) – becoming the only player to attain that honour while at the club.

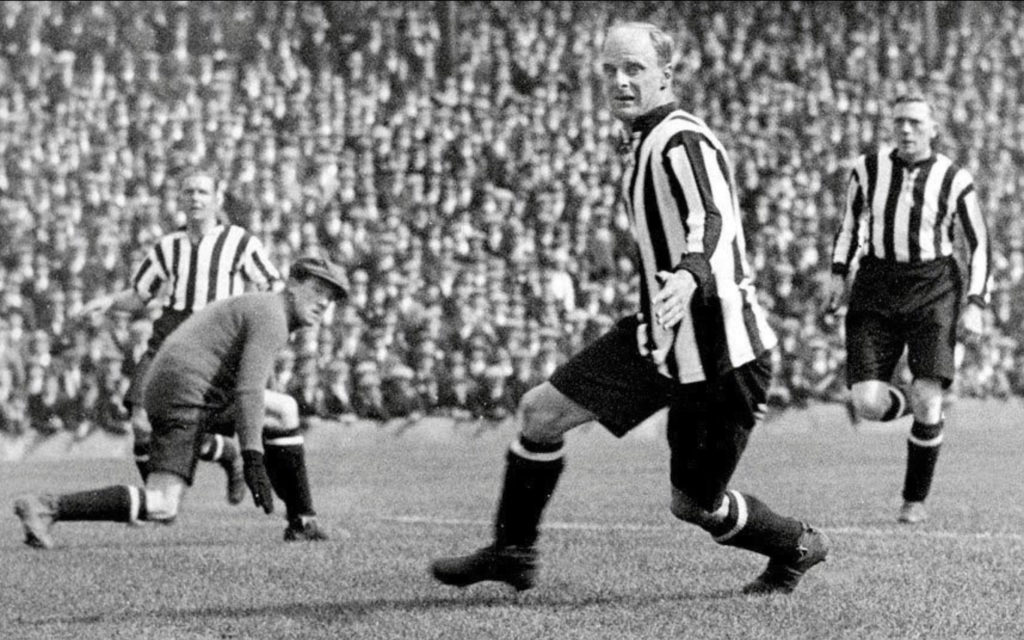

Warney was close to his brother, Frank, and was delighted that his sibling was already at South Shields when he signed on the dotted line. Frank had also represented England Boys and would join Warney at his next port of call – Sunderland. A record £6,000 bid in March 1922 was too high for South Shields to refuse, so Warney joined the Wearside club. He partnered Ernie England – whom he rated as one of the greatest full-backs and a master of the tackle. In contrast, Warney’s game was more about not committing to a tackle – instead he would jockey the opposition winger or inside-forward away down blind alleys. This approach, which was not dependent on having great pace, extended his career well into his thirties.

The epitome of calm, Warney received this warm praise from teammate Charles Buchan: ‘He looked a move ahead, and with his shuffling stiff-legged canter took up the best position to check the opposition. He seldom tackled an opponent when he had possession of the ball. He stood beside him, and at times moved along with him – until he practically forced him to part with the ball. Whatever happened, Warney was not really beaten. He was usually between the opposing forwards and his goal.’

Sometimes known as The Iceberg as he was so hard to read, he made forwards up against him overthink, becoming preoccupied with what Warney was going to do, rather than their own next move. Raich Carter touched on this: ‘Therein lay the true secret of the cool and calculating Cresswell. So infallible did he seem that he thrust the onus of proof of your ability entirely on you as an opponent. He has the poise and quiet self-confidence that enabled him to play something bordering on a cat and mouse game. In his face you almost detected the invitation to you to make your move, and from his calm approach you suspected he already had a fair idea of what move you might be making.’ Carter would also compare Warney’s footwork when facing his own goal to that of a ballet dancer: ‘He would feint as if to kick back to his keeper, enticing the forward dash forward, intent on an interception, before swivelling over the ball moving back upfield.’

Silverware eluded the Rokerites in Warney’s time there, but this ‘thinking-man’s full-back’ won five more England caps (one in a fixture at Goodison Park) and cemented his reputation for exquisite defensive timing. On one occasion, however, his timing was very much awry. He would habitually commute by train from his South Shields home to Roker Park and get there with time to spare. But for a snowy Christmas Day fixture he arrived at the station to learn that there was only a skeleton rail service in operation. After frantic and futile attempts to hail a taxi, he waited for a train to eventually turn up. Dashing on foot from the destination station to the ground, he was puzzled to see supporters heading away from the stadium. Had he actually missed the whole match? To his relief he was informed that the condition of the pitch had made play impossible.

His second England cap came in May 1923 at the Stade Pershing in Paris. England ran out 4-1 winners and it was the slender, fair-haired right-back who grabbed the headlines in the French newspapers by repelling the French attacks without even breaking into a run. Teammate Charlie Buchan recalled it being: ‘one of the best exhibitions of back play it has been my pleasure to watch.’

As far back as 1921 Everton had been monitoring the assured full-back. They thought that they had negotiated first refusal on him early in 1922 – but ended up missing out. Interest was reignited two years later, but the £5,000 fee quoted by Sunderland was deemed too high. With Warney unsettled on Wearside by the departure of Charles Buchan, Everton finally got their man in February 1927. A £4,750 fee for a 29-year-old may have raised eyebrows but he delivered nine years of immaculate service for the Toffees. He later lamented that that his younger brother Frank did not follow him from Roker Park to Goodison. He shared an Everton debut with Tom Griffiths and came out of a 2-6 drubbing at Filbert Street with some credit.

He soon found his feet at the School of Science and was later quoted saying: ‘I found Everton one of the finest clubs to be with, but I pitied the reserve players. Everton’s team was practically the same week after week.’ Within months of arriving at Goodison, he was awarded the club captaincy for the 1927/28 season. It was an astute move by the directorate, as the defender’s calm, assured, leadership steered the Dixie Dean-propelled Blues to the League title. The magnificent trophy was presented to the proud skipper by John McKenna, President-Chairman of the Football League after the ultimate match of the season, against Arsenal. Warney would retain the captaincy for a further season before ceding it back to Hunter Hart. He was given his seventh, and final cap for England at the age of 31, a defeat of Ireland in October 1929.

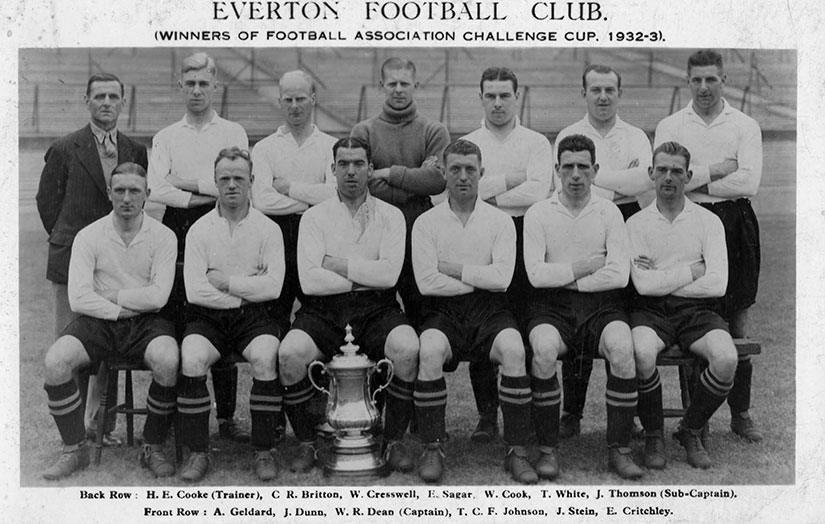

Having suffered the indignity of relegation in 1930, the full-back was a steadying influence as the Blues bounced back with immediate promotion and then secured another League crown in 1932. He moved from right to left back to accommodate the Welshman, Ben Williams (who succeeded Hart as captain). Injury to Williams saw Billy Cook signed from Celtic in 1932, and the pair made a silk and steel combination as the Blues progressed in the 1933 FA Cup competition. At the grand age of 35, he was in the team which beat Manchester City 3-0 in the final. The calm, avuncular exterior was in fact, something of a front. Before the cup final he was observed heading off to a quiet corner of Wembley stadium for a smoke of his trademark pipe. ‘To calm me nerves,’ he explained.

Warney developed a deep affinity with Merseyside (he lived in Birkenhead) as his granddaughter, Amy, recalls: ‘He absolutely loved playing for Everton and that is why he played there for as long as he did. Warney would tell my dad that was Everton was his favourite club – definitely more so than Sunderland, and even South Shields for that matter.’ He was a dog lover, being one of the first people in South Shields to breed German Shepherds. He also gifted Dixie Dean a greyhound which the famous forward named, naturally, Warney.

Warney felt that that he had a couple of seasons still in him at the highest level, but the heart-breaking decision to leave Goodison had been made for him. His final Football League outing had been at Derby’s Baseball Ground on 22 April, but he had a Goodison farewell on 30 April in a replayed Liverpool Senior Cup final against Liverpool. A 1-1 draw saw the trophy shared, with the Daily Post reporting that he bowed out having ‘rarely put a foot wrong.’

In partnership with Cook, the South Shields man remained a first choice full-back until the 1935/36 season. Will Cuff had once told the veteran that it was time to move ‘upstairs’ at the club, but he demurred, preferring to concentrate on playing. Nonetheless, his counsel was sought on team selection and he kept a fatherly eye on his younger club-mates on post-season tours. He always held the view that had he accepted the chairman’s offer, he might one day have managed the Toffees. But in the spring of 1936, Theo Kelly delivered the devastating news that his time as a Toffeeman was ending after 308 outings and one goal. It was fitting that as the Prince of Full Backs stood aside another regal player arrived in the form of Tommy G. Jones – who would come to be dubbed The Prince of Centre Halves.

So, at the grand age of 38, after 601 appearances, the player transformed into a manager. The offer of a coaching post in Spain was turned down (‘Eh, my dad was a bloody idiot,’ his son Corbett would ruefully state). There was also a long-standing invitation to manage in the League or Ireland. In his words he lacked the ‘push’ to go, but later rued his caution: ‘I often wish I had [gone] but, well, I made my decision.’

Closer to home, the managerial rookie rejected Chester FC (where his brother was playing) and, reportedly, Leicester City and settled for the Potteries, becoming Port Vale’s manager-coach (a new role for at club). He signed C.F. Dickinson from Everton and had former Toffee Jack Peacock as his assistant. At Vale Park he tried to introduce modern techniques in terms of fitness and training – as well as team-bonding activities such as billiards and snooker. He led Vale to a 11th place in the Third Division North, but the Valiant’s parlous financial position meant that they had to release Warney at the end of his first season.

Within a few days of leaving Port Vale, he walked into the manager’s office at Northampton Town, succeeding Syd Puddefoot. He swiftly persuaded his brother Frank to give up playing and become the club’s scout, declaring: ‘He’s the ideal man for the job – when I send Frank out, I know he’ll look at the game as if I were there.’ The Everton connection saw Channel Islander Elie Hurel switch from Goodison in 1938. Former utility man Tommy White, struggling with a knee injury, also came down from Merseyside for a trial. In May 1939, the Toffees, freshly crowned League champions ventured down to the County Ground for a benefit match in Syd Russell, a Cobblers player who had lost a leg after an injury.

The manager added the role of secretary to his title in the spring of 1939, but the outbreak of war brought about a hiatus in his managerial career. Although over the age of conscription, he enlisted as a PTI with the Army. Based near Derby, he was soon drafting in to running the camp football team (and taking to the field, himself), leading them to several trophy wins. Visiting family in the North East when on leave he would sometimes hook up with Dixie Dean, stationed at Barnard Castle, and take in a Newcastle match. He returned to Northampton after the war but discovered that the Cobblers had already filled the managerial post. He worked as a PE Instructor at the town’s technical college until a connection with Stanley Rous saw him take the reins at Southern League Dartford FC in 1946. He built the side up from scratch, even turning out himself when needed, but walking away when a director tried to dictate how he should run team affairs. Years later Warney would venture his opinion of some club directors: ‘For players there are definite standards that they stand or fall by. It seems a pity to me that there is no test of the qualifications of the men who stand behind the game. You can’t be sure that many of them are even interested in the game. How many, I wonder, would cross the street to see a match if they were not on the inside of football.’

(close to the site of Sunderland’s current stadium)

He returned to his native region, swapping football for the pub trade. With wife Grace, until 1956 he ran Scottish and Newcastle’s Sheet Anchor hostelry on Dundas Street, Monkwearmouth (close to the site of Sunderland’s current stadium). The children, Corbett (born in Birkenhead) and Audrey would be drafted in to assist Mine Host on evenings and weekends. With a golf handicap of eight, he’d enjoy a spot of golf at Simonside Hall on a Saturday. On the way home from his round he’d always get off the bus a mile from his Mortimer Road home: ‘Just a little bit of exercise to keep me fit’ he would explain.

Although less enamoured with the style of post-war football, he still hankered for involvement. Interviewed in 1947 for the manager’s position at Newcastle United, he was unsuccessful. He was also mentioned in connection with a head scout role at Everton in the 1950s (a post filled by Harry Cooke Jr. in 1958).

Sporting links were maintained through Warney’s son Corbett (named after Warney’s brother, killed in action during the First World War), a highly promising six-foot centre-half. There was a complicated relationship between father and son when it came to football, with an undercurrent of rivalry. When Corbett was in his late teens and attracting attention from a lot of club scouts, Warney put his foot down, stating emphatically: ‘I want him to get a profession’ although he conceded, ‘I can’t stop him playing football, because it is in him.’

Corbett duly gained his accountancy articles while continuing to play as an amateur for Bishop Auckland gaining international recognition. He was watched by the likes of Sheffield Wednesday, Derby, Wolves, Huddersfield and Everton, but, ironically, in light of his father’s allegiance, it was Liverpool that he came closest to joining as a professional. Don Welsh, the Reds’ manager, had wooed the Cresswells for some months but was keen to keep negotiations secret. However, Corbett had mentioned to his friend the inducements offered by Liverpool to sign. His friend, a budding journalist, leaked this to the press (it was one of Corbett’s great regrets). When news broke on the impending signing, Warney stated that he would be accompanying his son to live on Merseyside (‘I’d go tomorrow if I could’ he told one newspaper).

However, the leak had caused Liverpool to cool their interest, instead just signing Corbett as an amateur in September 1953. He went on to make a few Central League Appearances when his studies permitted but within a year his association with the Reds had ended. When no other top clubs came forward, he continued to represent Bishop Auckland and the national amateur side. Warney cast a long shadow, whenever Corbett was reported he was described as ‘the son of Warney’. Who was the better player? ‘Oh, probably me,’ Corbett shrugged, when pressed for an answer by his daughter. On the eve of Bishop Auckland’s fourth FA Amateur Cup Final, at Wembley, Warney praised his son, but reiterated his opinion about making a career in the game; ‘My son is, I think, one of the best three [centre-halves] in the country. But I would not dream of advising him to turn professional.’

Belatedly, Corbett did have a taste of Football League action, representing Carlisle United in 17 matches in the 1957/58 and 1958/59 seasons, but then chose not to re-sign. Remarkably, in light of his previous stance, Warney then announced to the press that his son should be signed by Newcastle United to solve their scoring crisis. He told the press that he was so confident in his son as a make-shift centre-forward that he would refund the transfer fee out of his own pocket if Corbett failed to pass muster in the black and white stripes. When asked for her thoughts, Grace told the press, ‘Oh, you’ve heard about it, have you? You know how Warney talks.’ The Magpies did not take him up on the offer.

Warney himself, would turn out for George Lillycrop’s Old Timers football team in an annual charity match, his final outing coming in 1958 being at the grand age of 60. Sometimes son and father would play alongside each other in these fixtures – ‘Kicking it with the old timers’ as Corbett used to refer to it.

Warney was very proud of his footballing achievements but had not time for sentimentality; he didn’t even display his medals and caps in the Sheet Anchor or at home. He did donate his first international shirt to the South Shields Museum but gave away his medals away to anyone with a bit of a sob story. Grace, used to his old England shirts as dusters for house cleaning duties – she would state categorically that made the best dusters in the world. ‘They would be worth a fortune now; I could weep!’ laments Amy.

Living and spending time with a sport star of yesteryear had its drawbacks for Grace and the two children. Warney was very well known and liked in his hometown, so walking down King Street, the main thoroughfare, would take two hours. He would get stopped by everybody and would not just say hello, he would have a chat for ten minutes – and then stop and chat to the next person! It would drive Grace up the wall, so she would go off and do the shopping without him. Warney’s grandson, Tim, recalls trips to South Shields from the Home Counties (and reciprocal visits by Warney). The pair would spend hours in the garden kicking a ball to one another. When not doing that Warney would be indulging in his passion for gardening or telling Tim tales of his playing career.

At some point in his sixties, symptoms of dementia emerged; Warney would increasingly live in the past, with little awareness of more recent events. Amy recalls: ‘Thankfully, he seemed contented in his condition and regularly took walks round the village. If Grace had to pop out, she would leave him in the house, but so many times she would come back and find him gone. But he was so well-known in South Shields, so someone would find him and take him back home. If someone had tethered their dog up outside a shop, he would often untie it, take it for a walk and turn up at home with it.’

Sadly, this Everton great was not well enough to attend the reunion for the 1933 Cup Winning Team at the 1966 FA Cup Final. The Prince of Full-backs passed away on 20 October 1973 South Shields General Hospital , at the age of seventy-five. He was laid to rest at Harton Cemetery in his hometown; his gravestone is inscribed with the words Peace in the Elysian Fields.

Thanks to:

Amy Cresswell-Fox

Tim Siddons

Bob Wray (South Sheilds FC historian)

Billy Smith

Richie Gillham

Everton FC Heritage Society

Sources

His one appearance for Hearts was on Sat 27 Nov 1915 Hearts 3 Dumbarton 1 not Morton as stated.