As was the capricious, romantic and, in some cases, downright fictitious nature of news reporting in the United States during his rise to prominence, myth and mystery surrounds pretty much everything Babe Ruth ever did.

His Called Shot during the 1932 World Series, for instance, is still shrouded in uncertainty, just like the fable that he once hit a Fall Classic home run to fulfil the last wishes of a sick kid in New Jersey. There’s no way to tell for sure whether these wondrous feats actually occurred, thanks in large part to the cliquey journalism culture of the age.

In those days, beat writers were paid by the team they covered and, frequently, they travelled on the same trains, slept in the same hotels, and drank in the same bars as the players, managers and executives. Thus, whether by design or osmosis, the work of said writers was typically drenched in hyperbole and fabrication, especially when it came to the eminence of star players, and most of all when it came to The Great Bambino.

After all, it served everybody to create this larger-than-life caricature, this baseball superman who did things nobody had ever seen on a diamond before. The writers stayed in favour with the players, who, in turn, used the publicity as a bargaining chip in contract negotiations. Meanwhile, the owners were largely happy, as fans flocked to the stadium, eager to see in person the hardball demigods largely spawned by the ink of knowing newsmen. It was all part of the self-serving hero machine.

Yet, there’s still something irresistible about Babe Ruth stories and, as a Merseyside lad, one such tale sticks out more than most to me: the enchanting yarn of the time he met Dixie Dean, the local boy who became arguably the greatest goalscoring hero in the history of English football.

Through the years, I’ve heard and read so many different interpretations of the story, it’s hard to separate fact from fiction. But that was, and continues to be, the beauty of The Babe: he was anything we wanted him to be, everything we needed him to be. He was The Sultan of Swat, The Colossus of Clout, The King of Crash. He was Babe Ruth, the great, big, lovable icon onto whom a nation could convey all its hopes, dreams and aspirations.

Dean was also a national treasure, but a treasure noticeably devoid of Ruth’s bombast and celebrity. Yet the pair had plenty in common. Dixie soared to fame in 1927/28 when, playing for Everton, he scored 60 goals in a single Football League season, establishing a sacrosanct record hitherto unbroken. Likewise, Ruth hit 60 home runs in ’27 for the mighty New York Yankees, a hallowed mark that, save for the Herculean effort of Roger Maris, has only ever been topped by chemically-enhanced fraudsters. Thus, at a special juncture of history, Babe and Dixie were the preeminent sporting icons on each side of the Atlantic, hence the effort, no doubt by publicists, to have them meet in London.

Dean was also a national treasure, but a treasure noticeably devoid of Ruth’s bombast and celebrity. Yet the pair had plenty in common. Dixie soared to fame in 1927/28 when, playing for Everton, he scored 60 goals in a single Football League season, establishing a sacrosanct record hitherto unbroken. Likewise, Ruth hit 60 home runs in ’27 for the mighty New York Yankees, a hallowed mark that, save for the Herculean effort of Roger Maris, has only ever been topped by chemically-enhanced fraudsters. Thus, at a special juncture of history, Babe and Dixie were the preeminent sporting icons on each side of the Atlantic, hence the effort, no doubt by publicists, to have them meet in London.

Some people set the Ruth-Dean rendezvous in 1934, but records confirm The Babe actually arrived in England, for his only known visit, via ship on 7th February, 1935. Ruth had just concluded a baseball tour of Japan on Connie Mack’s barnstorming All-Star team, and decided to travel onward through parts of Asia and Europe with his wife, Claire, and daughter, Julia. The party stayed in London for less than a week, enjoying the attractions and attending a host of different events.

However, attempting to discern exactly what events, on what days, can prove rather tricky. You see, popular wisdom dictates that Ruth and Dean met following an Everton-Tottenham game at Spurs’ White Hart Lane ground. Yet, only one round of fixtures took place during The Babe’s stay in London, and, that weekend, Everton thrashed Wolverhampton Wanderers, 5-2. Oh, the myth and mystery.

However, according to the My Eyes Have Seen the Glory website, seemingly a historical authority on Spurs, Babe Ruth did attend a football match at White Hart Lane, on Saturday 9th February, 1935, when the home team faced Derby County.

“New York Yankee baseball star Babe Ruth watches the match at White Hart Lane,” the site notes, “between the side who hosted a baseball side [Tottenham, who were British baseball champions in 1906 and 1908] and the one who introduced baseball into the name of their ground. [Derby, who played at the Baseball Ground, and were an early powerhouse of the sport in Britain.]”

So, the evidence is pretty clear: Babe Ruth did, at one time, visit White Hart Lane. Yet, historians have struggled to even place Dixie Dean in the same city, let alone the same stadium, as The Bambino on that day. Dixie played the full game as Everton pummelled Wolves at Goodison Park in Liverpool, almost 200 miles from Tottenham, where Spurs played concurrently. But Dean himself insisted that he met Babe Ruth and, more importantly, a few years before his death, the former Everton hero told journalist John Roberts that the gathering took place in the dressing room at White Hart Lane following a match.

Of course, it’s conceivable Ruth visited England on a different occasion, under the radar, but finding any reference to such an adventure is exceedingly difficult. It’s also possible, I suppose, that Dean simply got a few details wrong. After all, he was approaching his 70th birthday at the time of the interview, and was asked to recall a meeting that happened when he was 28. The memory would be a little murky, even for the best of us.

Despite all the uncertainty over dates and locations, I’m still pretty certain that Ruth and Dean met at some point, judging solely by Dixie’s detailed recollection, which, in itself, raises more questions than it answers.

Dean recalled to journalist Roberts his conversation with The Babe, who introduced himself in typical style by booming, “You’re that Dixie Dean guy!”

“Jeez, you’ll get some cash today,” Ruth supposedly said, referring to the big crowd, to which Dixie replied that he only received £8-per week.

“Jesus Christ,” concluded Ruth, “I’d demand two third of this gate!”

Again, confusion reigns here. Was Dixie playing in the game? Therefore, where Everton in town, calling into question the date on which the mighty duo supposedly met? It’s difficult to tell. Perhaps the pair were introduced after the Spurs-Derby game, but Ruth, totally oblivious to soccer, mistakenly thought Dean had played. Yet, if this is true, how did Dixie get from Liverpool to London in the space of, say, twenty minutes? Confusion, confusion, confusion.

I ultimately feel that Ruth and Dean did meet, but I honestly have no clue as to when, where, or how.

In a cultural sense, regardless of detail, the meeting served to highlight the obvious differences between sportsmen in England and America, and namely how much they were paid.

In 1935, The Babe earned $70,000, Dixie £400. Ruth once famously earned more than Depression-Era President Hoover, because, as he quipped, “I had a better year than him.” Dean, meanwhile, was dogged by the Maximum Wage, upheld by the FA in an effort to stop footballers’ pay escalating beyond that of an average skilled labourer.

The difference in pay of star athletes on either side of the Atlantic was a multifarious issue, with economic, political and geographic undertones. In 1929, the Yankees generated an income of $1.3m, as Stefan Szymanski, a leading sports economist, writes in National Pastime, “while Everton, who won the Football League championship in [Dean’s] record-breaking year, had an income of only $255,000.

Yankee Stadium, a cathedral built to accommodate Babe Ruth’s enormous popularity.

“In dollar terms, the Yankees paid out $366,000 in salaries in 1929, while Everton paid out $63,000. Even if we allow for the difference in scale, Dean was as big a star in English soccer as Babe Ruth was in baseball. Ruth received nearly 20 percent of the Yankee payroll, but Dean was paid only 3 percent of Everton’s.”

Ultimately, baseball owners of the age were like circus managers, willing to pay top dollar for the acts most likely to fill the seats. Football owners, on the other hand, were famously parsimonious and grumpy. Hence the disparity in pay between the two sports.

During his visit to London, The Babe also tried his hand at cricket, smashing balls all over the grounds. “How can I help it,” he asked, “when you have a great wide board to swing?” Ruth enjoyed the game, but offered a damning assessment of its pay structure. “It’s a better game than I thought,” he concluded. “But I think I’ll stick to baseball. They tell me $40 a week is top pay for cricket. In that case, I believe I had rather be a club owner than a player.”

I’m just enthralled by this whole tale, this whole idea of Babe Ruth, ever brash and boisterous, gallivanting through sleepy England and attempting to put his stamp on its values. In particular, the central story, that of his meeting Dixie Dean, is unendingly compelling, largely because they were so similar.

At the same moment in history, they were the largest heroes in their respective countries. They were the most famous athletes in the world. They were living legends.

But, once, before they became Babe and Dixie, these mystical avatars of national pride, they were just George Herman Ruth and William Ralph Dean, two unruly boys from rough beginnings trying to get by.

Ruth was born in Pigtown, a tough neighbourhood in Baltimore, one of America’s most blue collar cities. He was something of a rascal, sent, at the age of seven, to St Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory for ‘incorrigible’ children. Dean, in turn, was born in Birkenhead, a working class, rough-and-tumble shipping town across the River Mersey from Liverpool, located barely five miles north of my family home on the Wirral peninsula. Young William was a wannabe street urchin, eventually dispatched to Albert Industrial School, a Birkenhead borstal, where he falsely told friends that he had been caught thieving.

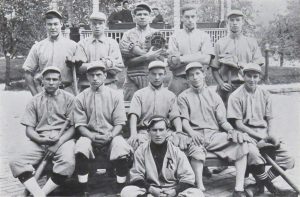

The Babe at St Mary’s, back row, middle.

Ultimately, nothing much was expected of either boy. They were just ragamuffins from fairly downtrodden towns, destined for lives of anonymous toil and labour. Perhaps Ruth would follow his father, keeping bar at local taverns. Maybe Dean would become a railwayman like his Dad. Those were the best case scenarios, until each kid discovered the respective sport that would elevate him from relative squalor, into the stratosphere of global fame.

Ruth discovered baseball at St Mary’s, whereas Dean, always a keen footballer on the cobbled streets of Birkenhead, honed his craft on the pitches at Albert Industrial. Both had preternatural talent, as if by divine intervention; talent that, one day, would totally revolutionise the way their respective games were played.

But, before reaching the very top, both heroes made humble stops playing for smaller teams. Ruth caught on with the minor league Baltimore Orioles, en route to glory with the Boston Red Sox and eternal fame with the Yankees. Dean, meanwhile, started off at lower league Tranmere Rovers, my beloved club, before scaling new heights with Everton and England.

From there, they both went on to enjoy unprecedented success. Ruth hit 60 home runs and became The Caliph of Clout, the looming emperor of baseball. Less than a year later, Dean scored 60 League goals and became Dixie, the towering God of football. Perpetually apart but forever linked, they systematically rewrote the history books.

And one day, they finally met. We think. We hope.

Of course, parts of the Ruth-Dean story are undoubtedly embellished. But isn’t that why we love it, along with all the other improbable tales? I’m a hopeless romantic when it comes to Babe Ruth and, for the sake of baseball history, I tend to tune out the naysayers and prefer instead to indulge in the glorious depth of his grand mythology. This particular story, involving the prodigal son of my hometown, the greatest footballer ever to represent the club I love, is without doubt one of my most cherished, even if it didn’t happen exactly as we think.

permission given by Ryan Ferguson

https://baseballineurope.wordpress.com/ryan-ferguson/