Everton 2 v 1 Accrington

Football League Division One, 8 September 1888

Anfield – Attendance: 12,000 – Referee: J Bentley

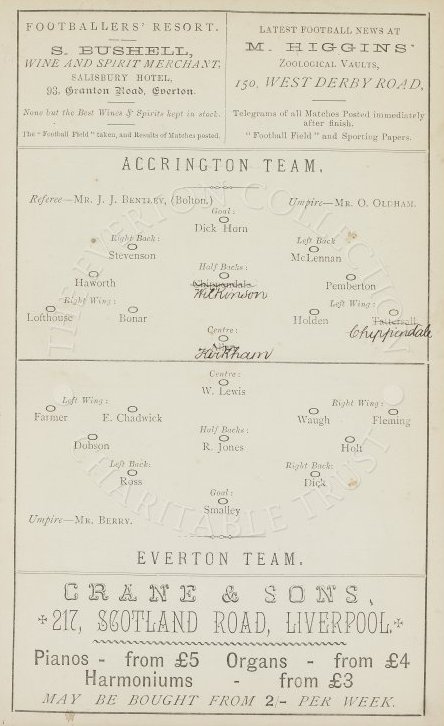

Everton: Smalley, Dick, Ross, Holt, Jones, Dobson, Fleming, Lewis, Chadwick, Waugh, Farmer

Accrington: Horne, Stevenson, McLellan, Haworth, Pemberton, Wilkinson, Lofthouse, Bonar, Holden, Chippendale, Kirkham

It started with just twelve. A dozen trailblazers striking out to create what would become the greatest football league in the world (at least until the Premier League ruined the top flight with its orgy of consumption, its vapid razzmatazz, and its Jamie Carraghers).

The 8 September 1888 represented a watershed moment in English Football. After decades of tournaments, exhibition matches and cup competitions, the game would finally become structured, better organised and more recognisable as the sport that we love and loathe in equal measure today.

For those like Everton, who formed part of that inaugural band of brothers, the creation of the Football League marked the culmination of a journey that had taken them from knock-around kick-abouts down the local park, to become the elite of the fastest growing sport in the country.

Why Everton had been chosen while others bypassed, was in no small part attributable to the club’s hunger to embrace professionalism.

Despite efforts by the FA to uphold the amateur ethos, including the fining or suspending of any clubs who were caught offering players financial reward, professionalism had eventually been legalised in 1885. The FA had acquiesced after being shaken by threats issued by northern clubs that they would establish a rival football authority unless the practice, which was widely in illegal use anyway, was made legal.

Throughout, the impetus for this change had largely come from teams of the north-west, specifically those based in Lancashire, who saw that success was there for the taking for those willing to pay for the best.

By accepting this reality, Everton surged ahead of local rivals. The club, according to early Everton biographer, Thomas Keates, ‘followed the light’. They sensed the way that football was travelling and took the necessary path. It’s telling that former peers that stayed true to amateurism, such as Stanley, Burscough and Earlestown, would fade into obscurity, while Everton thrived in the ‘new football’.

The club’s embracing of professionalism, combined with Anfield’s development and Everton’s impressive competitive performances, caught the eye of one William McGregor, a committee member at Aston Villa and the driving force behind the creation of England’s first national competitive league.

Concerned at the disparity in attendances between cup matches and friendlies (the former being much more popular) and aware that clubs who employed expensive professionals needed a guaranteed list of attractive fixtures rather than a haphazard collection of games, McGregor sought to ape what had occurred in county cricket by creating a system of regular competitive matches involving the top clubs, centred around a league structure.

In a move that would have echoes 100 years later when the Premier League was created, McGregor sent a letter to four of the biggest clubs in the country (Preston North End, Blackburn Rovers, West Brom and Bolton Wanderers) inviting them to form a league where ‘ten or twelve of the most prominent clubs in England could combine to arrange home-and-away fixtures each season’. He also asked for their suggestions regarding which other clubs to invite.

If this was modern football, McGregor would probably have called his new venture something awful like, ‘FL12’, ‘Premier North’ or ‘The Super League’. But luckily, he had a bit more class and so the invites went out for what would simply and elegantly become, the Football League.

Were Everton a top club back then? The answer is probably not. What success had been achieved had been local in nature. On a more national level, in the FA Cup, the men from Anfield had not particularly impressed.

But that didn’t really matter. What McGregor and others really wanted was potential, and that meant clubs from big cities that had embraced professionalism. Although a surprise inclusion in the inaugural league and regarded as one of the weaker members, the club’s prescient realisation that football was changing, that the Corinthian spirit was ebbing away, had given Everton an important advantage.

On the opening day of the season, Everton joined the esteemed ranks of football’s elite to take part in a new league that comprised: Accrington, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley, Derby County, Notts County, Preston North End, West Brom, Wolverhampton Wanderers, and Stoke (renamed Stoke City in 1926).

Everton’s first opponents were Accrington. Just a week earlier, they had been defeated in a friendly against Everton’s great local rival, Bootle. The need to match what Bootle had done only added to the pressure of that opening day.

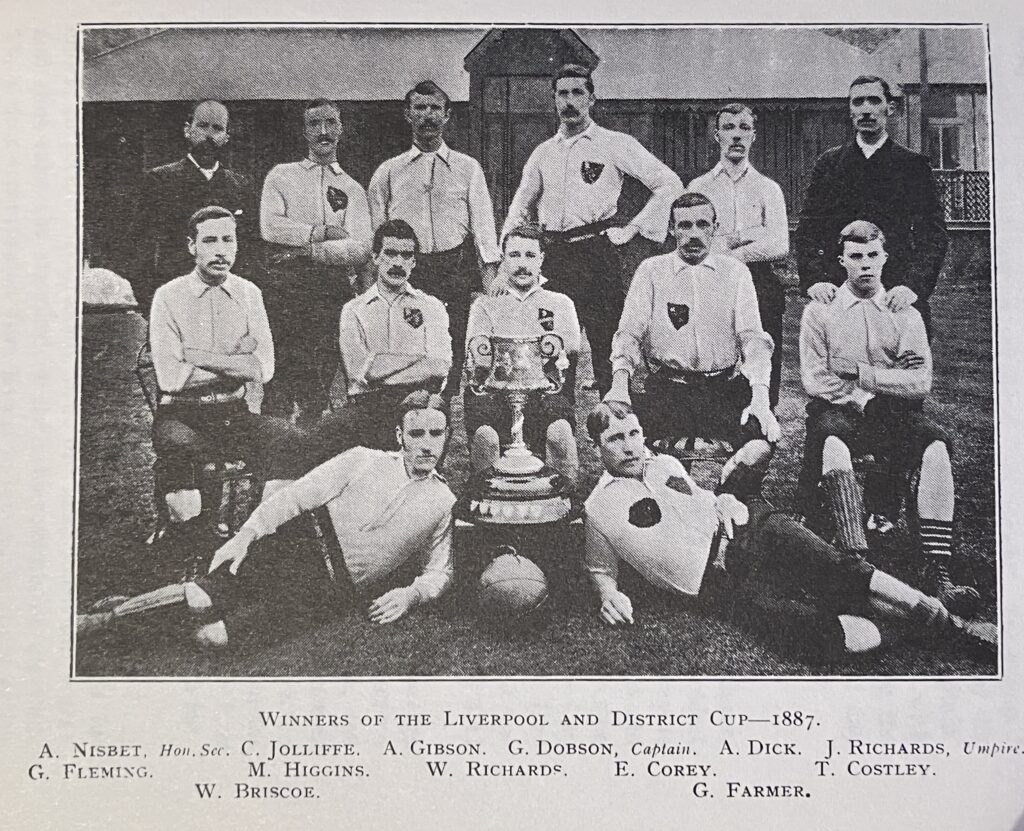

(The Everton Collection)

Around 12,000 turned up at Anfield to watch the match on a balmy September afternoon (although due to the lateness of Accrington’s arrival it was nearer to 4:30pm before the teams actually kicked off).

Both sides employed variants of the 2-3-5 formation, the ‘inverted pyramid’. It was attack minded but with the all important centre-half (then positioned in the centre of midfield) crucial when the play pivoted.

Despite their potential role as league whipping boys, Everton started on the front foot:

‘In the first half the Anfield crew had a decided advantage, and for a considerable time, play was almost entirely in their opponent’s quarter. But the splendid defence of the Reds, assisted to some extent by the inaccurate shooting of the home forwards, prevented them from scoring’, reported the Lancashire Evening Post.

Profligate in front of goal and squandering superiority, could there be a more ‘Everton’ way to start the club’s Football League career? As the half progressed, Everton’s dominance lessened and Accrington grew into the game. When half-time arrived, with the scores level, the match had become a more even affair.

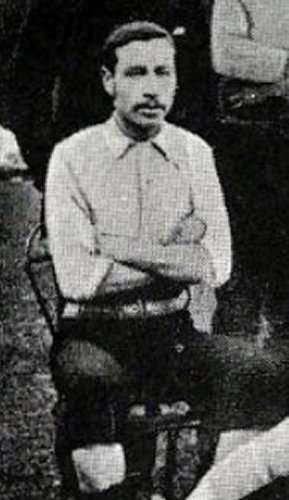

When play resumed after the break, the sides remained well balanced and it was unclear who, if anyone, would make the first breakthrough. Fortunately, for the majority of those who had come to watch, that particular honour would eventually fall to the home side. Ten minutes into the half, after a brief spell of intense pressure, the ball fell to Farmer, who whipped in a cross that Fleming met to head home the club’s first league goal. It was a strike greeted by a ‘tremendous cheering and waving of hands’, the Accrington Observer quaintly reported.

For more on Everton’s first ever goalscorer in the Football League, see Tony Onslow’s article ‘George Fleming: The Goalscoring Bank Clerk from Arbroath’

A few minutes after the opening goal, Everton were then the recipients of a huge slice of good fortune. After Horne had gone down low to save an effort by Chadwick, play was stopped when it was apparent that the Accrington keeper was in some discomfort. Ultimately, he had to leave the pitch with the pain too much for him to continue.

It would be a further sevety-seven years before a substitute was allowed to come on during a match in English football. In the game’s early days, if a player got injured, that team just had to lump it. And so, McLellan went in goal and Haworth dropped back.

Everton faced ten men for the remainder of the match and as is so often the case, capitalised on the numeric advantage when, Fleming got himself on the score sheet once again, meeting a cross from Farmer to make it 2-0.

At that point, the home side should have been cruising. But this, even then, was Everton, a club that never likes to take the easy path, never likes to give those watching too much comfort.

After the goal, observed the Evening Post, Accrington ‘kept up an almost constant pressure, swarming round the Everton fortress with a persistence which was certainly deserving of better luck.’

Crosses rained in, chances came and went, and the away side even hit the bar. It was like watching a Roberto Martinez defence in action; porous to the point of saturation. Eventually, the pressure told and Everton’s defence was breached, Holden beating Smalley with a free kick.

But despite continued pressure from the ten men of Accrington, the home side held out and managed to (just about) register the club’s first league win.

In less than a decade, Everton had come a long way. From that first kick-about on Stanley Park, this was now the biggest club in the city and as part of the new professional elite could proudly point to that win as proof that they merited their inclusion in the Football League.

Although the victors that day, it was a win that initially didn’t yield any points. Amazingly it was not until a few weeks after the start of the season that it was established that teams would receive two points for a win and one for a draw (as opposed to the initial idea of just measuring wins).

In that inaugural campaign, which was won by an unbeaten Preston North End, Everton finished the season eighth; chalking up nine wins, two draws and 11 defeats. It might have been unspectacular, but 20 points from a debut campaign wasn’t bad for a club widely seen as being slightly fortunate to have been there in the first instance.

It was enough to ensure that Everton would not need to apply for re-election, a fate that befell the bottom four of Burnley, Derby County, Notts County and Stoke.

Reservations had existed and doubt had hovered over Everton’s inclusion. But the club had defied and answered the naysayers in the best way possible. Everton had taken to League football. And in the years that followed would only make their inclusion all the more valid.

D.Waugh (Trainer), A. Hannah (Captain), R.E. Smalley, D.Doyle, R.Molyneux (Secretary);

A. Latta, J.Weir, J.Holt, G.Farmer, E.Chadwick: C.Parry, F.Geary, A.Brady

Bibliography

Lancashire Evening Post, 9 September 1888

Liverpool Mercury, 9 September 1888

Johnson, Steve, Everton Results Online

Corbett, James, Everton: The School of Science, DeCoubertin Books, (2010)

Titford, Roger, Football League, 1888-89, When Saturday Comes (WSC 225 November 2005)

Macpherson, Jon, ‘Accrington FC: The football club that would never die,‘ Lancs Live Online, (6 Sep 2013)

Wikipedia

Wikipedia, William McGregor

Wikipedia, Professionalism in Association Football

Wikipedia, Substitutes in Association Football

Wikipedia, George Fleming

Wikipedia, Football League in 1888–89

Wikipedia, Accrington F.C.