Everton and the Rise, Fall and Revival of Women’s Football

This December marks a centenary of one of the most significant football matches played at Goodison Park – but it did not involve Everton FC.

The participants were Preston’s Dick, Kerr Ladies FC and their St. Helens counterparts. The festive season match, in front of a record crowd for a women’s match, suggested that the women’s game was on the way to establishing itself as a mainstream spectator sport. 15 years later Dick, Kerr Ladies – rebadged as Preston Ladies – were back in the city, but were consigned to playing in a greyhound stadium. In spite of the presence of Dixie Dean, the crowd size was only a fraction of the one present at Goodison in 1920. How did this come to pass?

To set the scene, we should go back to the First World War years the Football League and FA Cup were suspended (Everton were reigning champions throughout the conflict). Many young men were serving in the forces or sent to the coal mines, so women were employed on the home front to help the war effort (by 1918, 700,000 were working in the munitions industry alone). Many of these female factory workers were also taking up football – both to boost wartime morale and to raise funds for deserving causes (normally military veterans’ charities).

With the support of Everton chairman W.R. Clayton, Goodison Park staged such a match on 1 April 1918, raising £150 for the Fallen and Disabled Footballers Fund. It was contested by Aintree Munitions Ladies and North Haymarket Ladies Football Club. The former had been formed in late 1917 at a shell factory and had, prior to the Goodison match, played all of their fixtures on the Wirral. Haymarket’s staunch defending held Aintree at bay in the first half but they conceded four second half goals. Ernest Edwards (Bee), of the Liverpool Echo, summed up what he’d witnessed with a mixture of encouragement and mild condescension:

Many must have gone to Goodison Park on Monday Morning for a pantomimical affair, and they had their eyes opened. There were laughable incidents of course but some of the players showed such good form that the possibilities of Ladies football had to be recognised…It is too much to expect the weaker sex to last 90 minutes’ football on the full scale of football’s [pitch] measurements. Whatever else the ladies have done, they have, in linking up with football, found a charity that has fared well, and promises to bring with it some football in the future.’

Aintree Munitions Ladies, after this high-water mark, would slide into obscurity, barely meriting a further mention in the local press. But a fixture on a far grander scale took place at Goodison on the morning of 26 December 1920 (Liverpool played at Anfield in the afternoon), when Dick, Kerr’s Ladies FC of Preston took on St Helens. The former team took its name from Dick, Kerr & Co. Ltd, where many of the players worked in wartime munitions production. Grace Sibbert, an employee at the Preston factory, had organised a game against male counterparts in late 1917. The following year the female team came under the stewardship of Alfred Frankland (a manager in the Dick, Kerr & Co. Preston factory). His dynamism and vision drove the team to become the best and most high-profile women’s team in the land. He’d soon seek talent beyond Preston, notably signing St Helens pair Alice Woods and Lily Parr. In the months prior to the Goodison Park match, Dick, Kerr Ladies had garnered much publicity through a series of ‘international’ matches played at home and across the English Channel against a ‘French XI’ team (actually the Fémina Sport club of Paris).

The pleasant weather on that Boxing Day morning drew an unexpectedly large crowd to Goodison – reported as being somewhere between 40,000 and 53,000. Additional turnstiles were opened as people swamped the surrounding streets, but many failed to get inside the stadium before kick-off. Such was the hubbub that the two teams needed a police escort to get into the stadium’s players’ entrance.

£3,100 (over half a million pounds at current values) was raised for the discharged soldiers and sailors funds in Liverpool (it might have been more but there was a suggestion in the Echo that female spectators were allowed in, unofficially at least, without charge). As for the match, Dick, Kerr, were simply too good for their Lancastrian rivals and struck four times without reply. Florrie Redford, the Dick, Kerr striker had missed her train to Liverpool, so Alice Kell, team captain and full-back, switched to centre-forward and bagged a hat-trick. After the game the Lord Mayor of Liverpool presented Kell with a trophy and each of the players received a medal in recognition of their charitable fundraising work.

The Daily Post wrote, “Dick, Kerr were not long in showing that they suffered less than their opponents from stage fright, and they had a better all-round understanding of the game. Their forward work, indeed, was often surprisingly good, one or two of the ladies showing quite admirable ball control.”

‘Old Red’ of Swallowhurst Crescent wrote to the Echo some years later to reminisce about the match. He singled out the Dick Kerr left-back plus the St Helens goalkeeper for praise. But the headline grabber for him was Dick, Kerr’s inside-left forward: ‘Miss Harris was a veritable box of tricks and roused the large crowd to the high pitch of enthusiasm.’

Subsequently, 35,000 spectators watched Dick, Kerr play take on Bath at Old Trafford. A return to Liverpool – this time at Anfield – drew 25,000 people to witness a 9-1 demolition of a ‘Rest of Britain’ team. But that memorable match at Goodison on Saint Stephen’s Day would prove, in hindsight, to be the zenith. All too soon, public interest in the sport was on the wane. The novelty value to some was fading but, perhaps more importantly, the attitude of the media was increasingly circumspect perhaps reflecting the reactionary stance of the football (and wider) establishment.

Dick Kerr Ladies

The high attendances at some women’s matches were felt to be a threat to the men’s game, which was still recovering after the war. Furthermore, there was a political angle. Dick, Kerr Ladies had not restricted their fundraising to war veterans’ organisations. In 1921 they (and other women’s teams) had played fundraising matches to give financial support to coal miners and their families, who were locked in a bitter dispute with their employers over cuts to wages (following the re-privatisation of the collieries). The families of some Dick, Kerr players hailed from Lancashire coal mining areas, so there would have been a strong sense of solidarity. These charitable actions would have been perceived as overtly socialist – and therefore hostile – by those in the corridors of power.

There were also mutterings from some corners that Albert Frankland was, at best, slap-dash and, at worst, dishonest when it came to accounting for the Dick, Kerr team’s income and expenditure. Then, of course, there was the hokum trotted out by some ‘medical experts’ (male and female), arguing that playing football was not only unbecoming of a lady, but also far too physical in nature for the female body.

A combination of the above factors pushed the Football Association into action. On 5 December 1921, it issued the following resolution:

Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, the Council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged. Complaints have been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of the receipts to other than charitable objects. The Council is further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to charitable objects. For these reasons the Council requests the clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.

Subsequently the FA tightened the noose by forbidding qualified match officials from overseeing women’s games. Almost overnight, the sport was robbed of its legitimacy and venues. Pushed to the very margins of the national sport, club’s came together to form the short-lived English Ladies Football Association (ELFA). Dick Kerr’s Ladies FC – effectively a semi-professional concern at this point – declined to join this body, which had an amateur ethos. Helped by their fame, Frankland’s team was able play at sports grounds not affiliated to the FA and embark on tours (including a chaotic one in North America in 1922). The ELFA folded with 12 months and many women’s clubs fell by the wayside.

Dick, Kerr Ladies FC changed name to Preston Ladies FC in 1926, after Frankland fell out with the business that had given the team its name (Dick, Kerr had, in fact, become part of English Electric by this point). Nonetheless they were still commonly referred to as Dick, Kerr Ladies by the general public and press. In their new incarnation, they returned to Liverpool on 10th August 1935 for a match in aid of charitable hospitals on Merseyside, The venue chosen was Breck Park Greyhound Stadium, on Townsend Lane, near Tuebrook. The match was billed as the ‘English Ladies’ team’ against a ‘French Ladies’ team (Preston Ladies sometimes competed under this national moniker, wearing white shirts instead of their regular stripes)

To add a sprinkling of stardust, and boost the gate, the great Dixie Dean was present to meet the team captains and carry out the ceremonial kick-off. He roped in some Everton colleagues for the occasion. Andy Tucker, Assistant Trainer to Harry Cooke was the referee and Toffees players Alex Stevenson and T. Kavanagh ran the lines. Breck Lane Stadium had been opened in 1927, one of four greyhound tracks in the city. In October 1927 Dean took time out from his record-breaking goalscoring season to acquire a greyhound called Poor Pat (the name taken from the Irish song ‘Poor Pat Must Emigrate’). Pat’s match up with Double Reel in a 500-yard dash at the Stanley greyhound stadium on Prescot Road generated some column inches Trapper’s Talk section of the Echo. In the build-up Dean was pictured taking Pat on a practice run over the jumps, he was accompanied by Everton winger Ted Critchley who was doing the same with Double Reel. Sadly Pat failed to match the dizzying success of his owner and before 1928 was out had been sold on to Double Reel’s owner. Dean’s ongoing interest in the sport, and the fact that Everton director Jack Sharp was a director of the Breck Lane Stadium, go some way to explaining why he was asked, and agreed, to attend the women’s match in 1935.

The fixture had some advance publicity in the Merseyside press through adverts and mentions the Echo’s ‘Hive’column. Bee noted: There is a friendly, but very definite, rivalry between the two teams. Each thinks the other is good – but not quite good enough to beat them. And there is only one way to settle that sort of argument. The odds are slightly in favour of our own girls but you never can tell when you’re up against the Gallic temperament.’

Prior to the match, the French players were entertained at a reception in Liverpool Town Hall, hosted by the Deputy Lord Mayor. Anticipating a decent crowd, additional trams were laid on by the corporation. In the event, 5,000 paid the 1/- admission fee at the turnstiles. Commenting on the match, Bee wrote that ‘England’ was the more ‘combined’ side whilst the ‘French girls worked well together’ but failed to trouble Miss B. Cunliffe between the posts for England (one wonders if she was related to the England international forwards – and cousins – Jimmy and Arthur Cunliffe, of Everton and Blackburn, respectively).

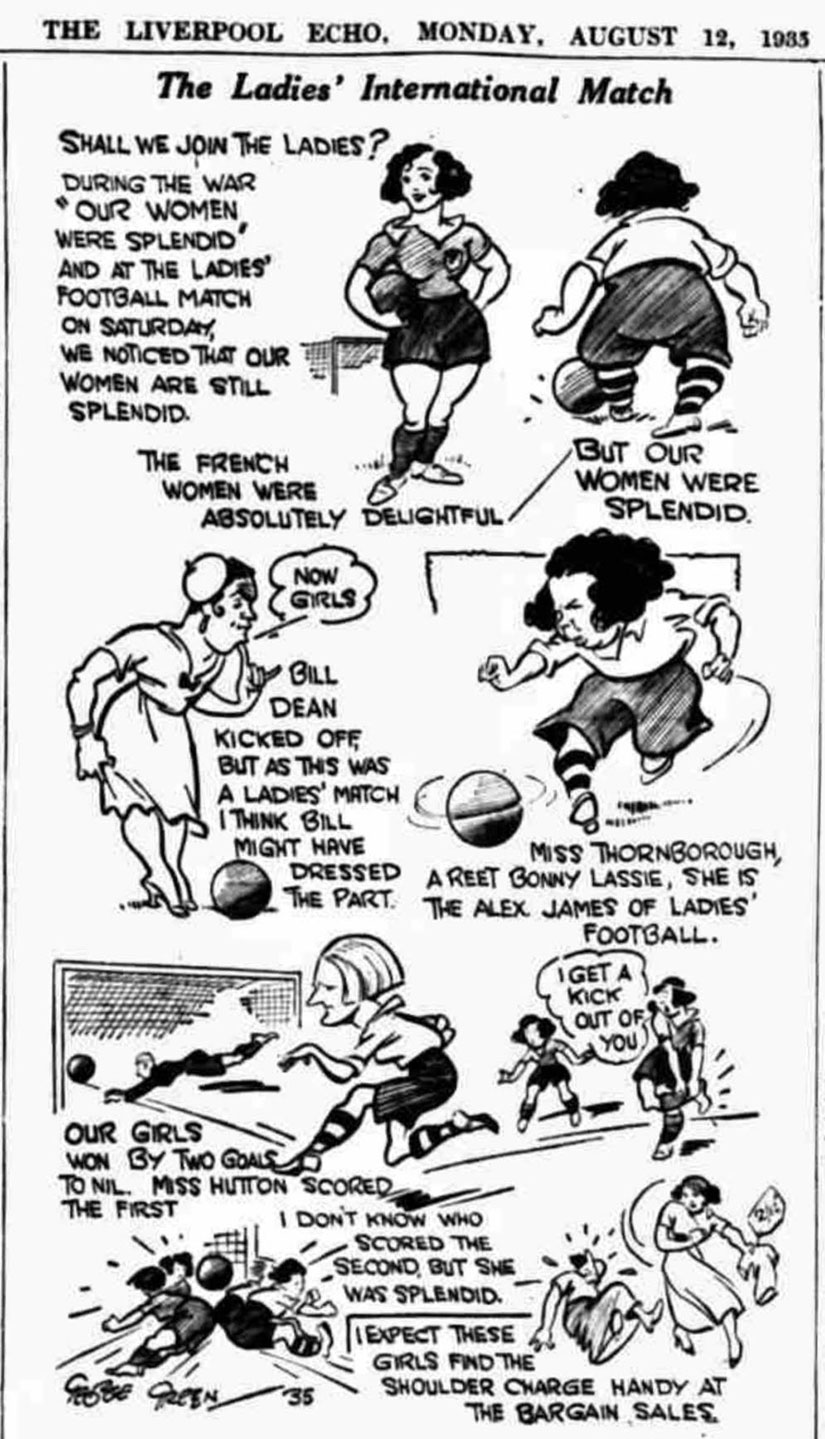

The result of the encounter was decided by two England goals after the interval. Edith Hutton scored with a fine solo strike (nicknamed Ginger, Hutton would score a hat-trick in the unofficial ‘Championship of the World’ match against Edinburgh Ladies in 1937).The lead was doubled through a scrambled effort with A. Lynch and E. Hodgkins ‘both rushing the ball over the line.’ The Echo featured a cartoon strip describing the match with ‘of its time’ humour.

Breck Park Stadium was damaged by bombing during the Second World War but continued operating for greyhound racing and boxing bouts until a fire damaged the buildings irreparably. It was demolished in 1953.

In 1971 the FA’s myopic decision to cast women’s football out into the wilderness was rescinded, but so much damage had been done. Dick, Kerr/Preston Ladies FC had folded six years previously, after playing in excess of 800 matches.

Everton Ladies team began life in the 1980s as Hoylake WFC, merging with Dolphins Youth Club to become Leasowe WFC. In 1989 Leasowe Pacific, as it was then known due to a sponsorship deal, won the Women’s FA Cup. The club came under the umbrella of the Everton brand in 1995 (something Peter Johnson deserves credit for). They won the Premier League title in 1998 and, guided by the inspirational Mo Marley, became one of the top teams in the land in the 2000s, winning the Premier League Cup in 2008 and the FA Cup two years later. They missed out on the 2009 League title on goal difference. The team has played a number of matches at Goodison Park, following in the footsteps of Dick, Kerr and St Helens. Now properly assimilated into the Everton set-up (reflected in being known simply as Everton), the women’s team has a new home at Walton Hall Park – a five-minute walk from Goodison. Under the stewardship of Willie Kirk the team reached the final of the 2019/20 Women’s FA Cup.

Everton Ladies parade the League trophy at Goodison before a men’s match in 1998

Former Everton and England players Rachel Brown-Finnis and Rachel Unitt have been inducted in the National Football Museum Hall of Fame. They followed in the footsteps of Lily Parr, the Dick, Kerr Ladies great whose playing career spanned three decades. Posthumously, she was one of the inaugural inductees into the Hall of Fame in 2002 – alongside the likes of Dixie Dean, George Best, Sir Stanley Matthews and Sir Bobby Charlton. In 2019, the Museum gave further recognition to Parr’s standing as a women’s football and LGBT+ rights icon when a statue was unveiled in her honour.

Article copyright: Rob Sawyer (2020)

Sources

bluecorrespondent.co.uk (Billy Smith’s Blue Correspondent website)

dickkerrladies.com

tranmereroverspast.wordpress.com

Wikipedia

Liverpool Echo

Daily Post

Daily Mirror

The Secret History of Women’s Football – Tim Tate

Rob Mitchell

Mike Royden

Emma Wright-Cates

Images

Dick, Kerr ladies team photo: from Wikipedia

Dixie Dean and Andy Tucker with the team captains: Rob Mitchell (grandson of Andy Tucker)

Greyhound photo, 1935 match advert, cartoon and Liverpool Town hall reception images: Liverpool Echo

1935 match action: Daily Mirror

Everton Ladies with the League trophy at Goodison Park 1998: Emma Wright-Cates

Lily Parr statue: National Football Museum

Further reading:

In a League of their Own! – Gail Newsham

The Dick, Kerr’s Lady – Barbara Jacobs

The Secret History of Womens’s Football – Tim Tate

Faith of our Families – Everton FC: An Oral History – James Corbett (section on Everton Ladies researched by Jack Gordon-Brown)

I researched and wrote the book you prefer to, about Alic Woods and Lily Parr and the social history of their lives and times, and their town, St Helens, where I was born.

I now live in Walton.