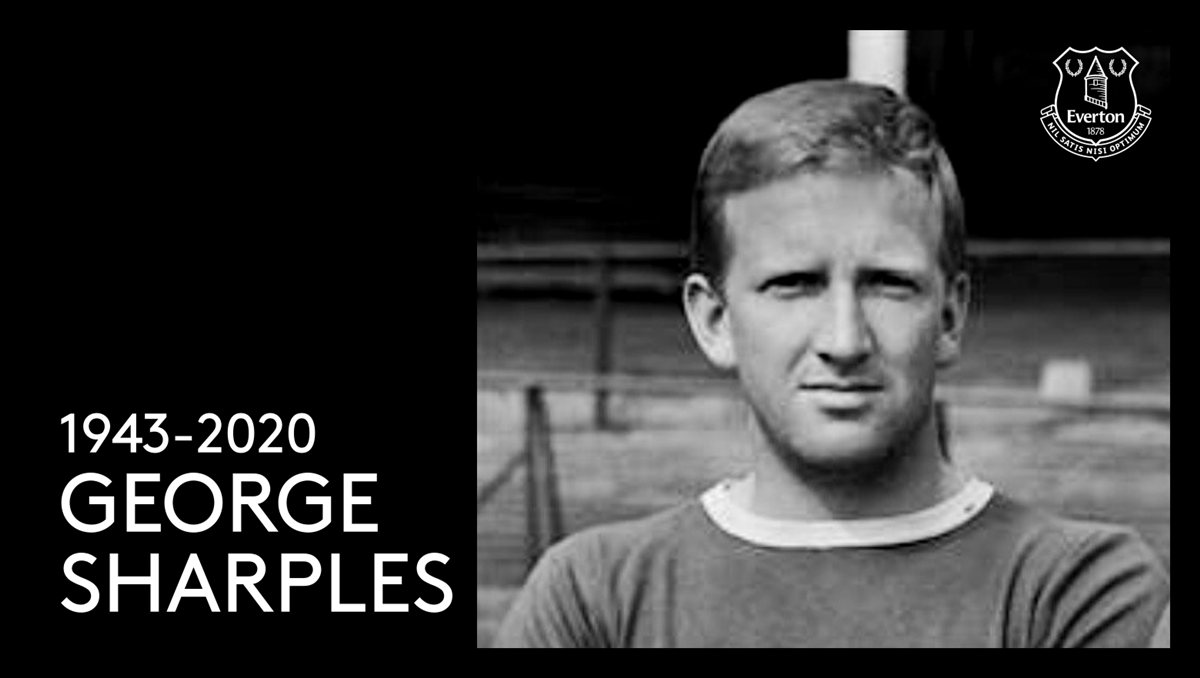

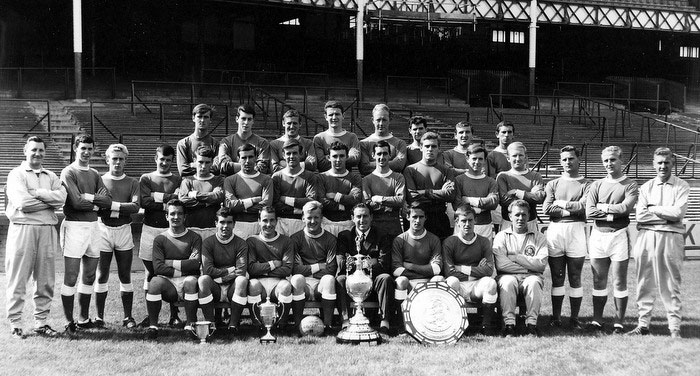

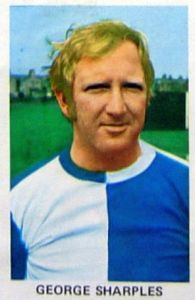

George Sharples, who passed away on 14 December 2020, aged 77, had been one of nine surviving players to have played a part in Everton’s title-winning season of 1962-63 (the others being Jimmy Gabriel, Mick Meagan, John Morrissey, Derek Temple, Tony Kay, Billy Bingham, Ray Veall and Frank Wignall).

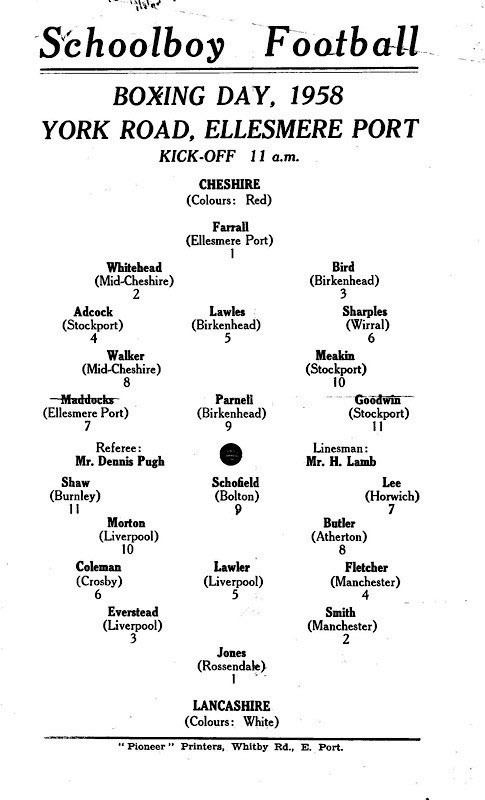

A son of Ellesmere Port, he was born on 20 September 1943, to parents James and Florence, who ran a large and successful newsagent business in Overpool. A student at Wirral Grammar School – a rugby-playing establishment – George always had soccer as his first sporting love. He represented Wirral and Cheshire Schoolboys (along with Roy Parnell, who would become a close pal at Everton).

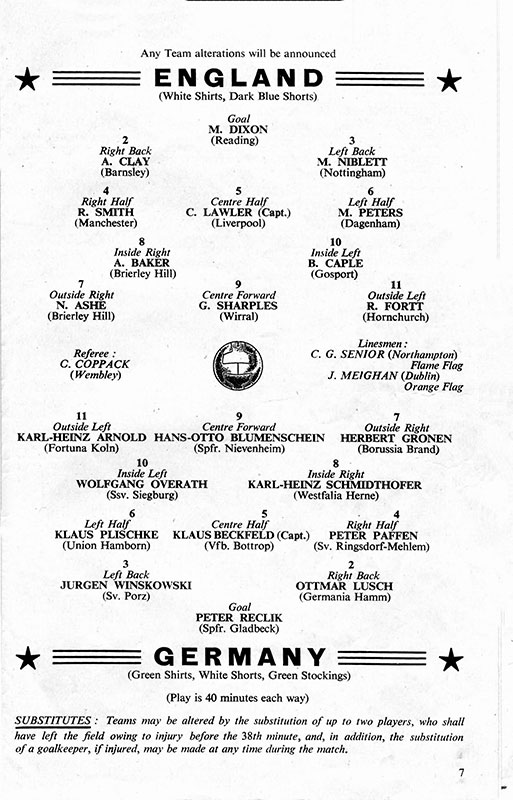

In April 1959, George was selected at centre-forward (his normal position was wing-half) for an England Schoolboys fixture against West Germany. That team was managed by Billy Roberts – an Ellesmere Port high school teacher and something of a mentor to young George. At centre-half for England was Chris Lawler – a future Liverpool star – whilst the left-half was Martin Peters. On the opposing side was Wolfgang Overath – he’d meet Peters again in a more significant international match at Wembley, seven years later.

Naturally, George came to the attention of Wirral-based Everton talent-spotter, Tom Corley (who had previously pointed Joe Mercer and Dave Hickson in the direction of the Toffees). He was brought to Goodison in the face of interest from Wolves and Manchester United (George’s father was keen on his son becoming an Everton player). He joined in July 1959 as a 15-year-old amateur on the ground staff. He already had the burden of being compared to Duncan Edwards by some sports journalists – a rather lazy comparison even though the two played in the same position.

At the time of the signing, Mike Charters had noted in the Liverpool Echo: ‘He is exceptionally well built for his age and, even at this early stage, possesses all the attributes of a class player. I saw him several times last winter when he captained Wirral Boys. He stood out head and shoulders, physically and in ability, over his colleagues and he has a calm sensible approach to the game which should enable him to climb to the top.’

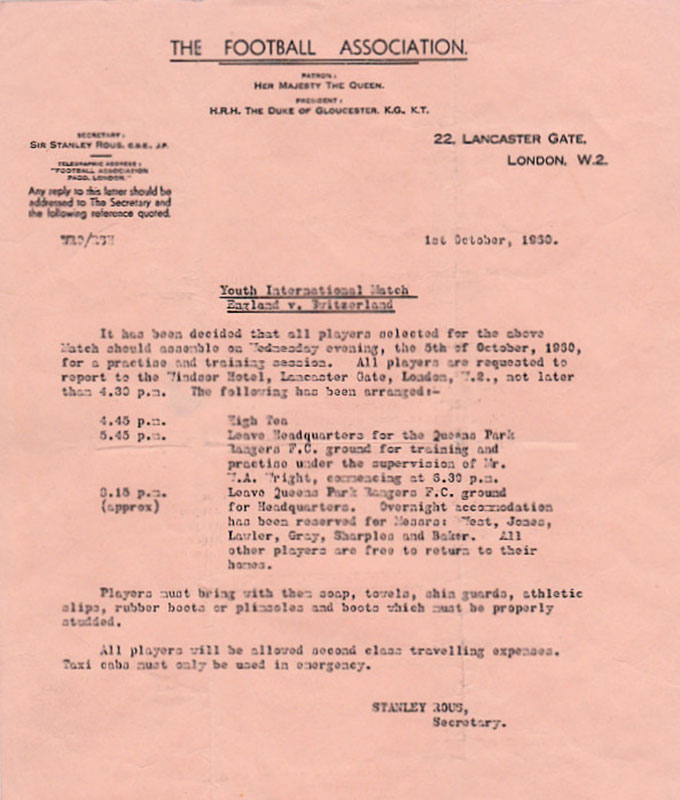

Under the tutelage of former Everton half-back, Stan Bentham, George turned professional on reaching his 17th birthday, and, in September 1960, he was called up to the England Youth side to face Switzerland at Brisbane Road on 8 October. He received a fairly curt communication from Stanley Rous at the FA:

Players must bring with them: soap, towels, shin guards, athletic slips, rubber boots or plimsoles and boots, which must be properly studded. All players will be allowed second class travelling expenses, Taxi cabs must only be used in an emergency.

His first-team debut, at Goodison Park, came less than a month later, on Bonfire Night. He was drafted in for the injured Jimmy Gabriel at right-half against West Bromwich Albion. The step-up to the hurly burly of the First Division was a huge one for the 17-year-old, and he struggled to acclimatise to the pace. Horace Yates of the Daily Post reported:

‘His [Jimmy Gabriel’s] inability to play gave the crowd an opportunity to see 17-years-old George Sharples, who only became a professional in September, in his League baptism. The lad made mistakes rendered less costly by the fact that Parker gave his best display for weeks, with an all-round exhibition that bore the obvious stamp of class, but I personally was thrilled with the promise of Sharples. He reminded me for all the world of a village lad, accustomed to seeing traffic slowly winding its way through the narrow streets, suddenly being taken out for the first time to a great motorway, and standing in amazement at the sight of unrestricted speed.’

Leslie Edwards, in the Liverpool Echo, reached a similar conclusion based on the first showing:

‘My first view of young George Sharples, who has been nursed along assiduously for so long, showed him to be too lethargic and lacking in zip to fit happily into his debut in the First Division. It could be that he is not attuned, physically or mentally, to the tremendous speed at which football is played in the top class.’

Of course there was no disgrace in having a difficult baptism with the senior side – many excellent players have failed to shine when stepping out as a first-teamer for the first time. George told me: “When I made my debut at 17, I wasn’t really ready, but Alex Parker, our right-back, looked after me. That was how it was in those days. Not everyone had a good game but you looked after each other – on and off the pitch. There was a good spirit.”

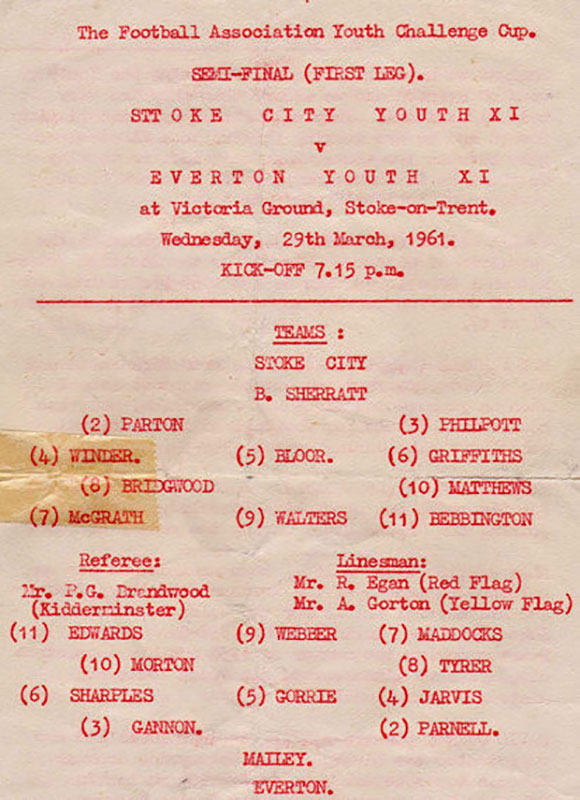

He was recalled to the first team in the following January for a match against Wolves – slotting in at left-half with Brian Harris moving to the left-wing. Everton crashed to a 3-1 defeat and, sadly, were winless in George’s four further appearances that season under Johnny Carey. George was part of the Blues’ side that reached the 1961 FA Youth Cup Final but lost 5-3 on aggregate to a very good Chelsea team.

Mick Meagan, who was in and out of the Everton team in this era, reflected: “George was one of the young boys when Les Shannon was coaching there. There were about five or six young fellows in that group – like George, Roy Parnell, Mick Gannon and Alan Jarvis. They were all good footballers and always great fun to have around – there was never a dull moment! George was a great young character and a real “country young fellow” in his tweeds etc. He was a very good player and everyone thought he would go further. He was just a great guy and always good for a laugh.”

With Johnny Carey sacked in April 1961, Harry Catterick came in. The new manager did not see fit to select George for the entirety of the 1961-62 campaign but George earned a recall in the third match of the Championship-winning 1962-63 season. Although struggling with a back injury, he was declared fit to replace the (also-injured) Jimmy Gabriel for the visit of Catterick’s former club, Sheffield Wednesday. Horace Yates sang the praises of the half-back’s display in his column:

‘A youngster who really delighted me was young George Sharples. A season has made a transformation in his play. Quicker in his movements yet seldom hurried in his play, his football brain is obvious. So often did he do the right thing, and do it immaculately that this powerful fledgling lends encouraging strength in a department where first line solidarity is essential.’

Naturally, Gabriel reclaimed the Number 4 shirt when fit again, four days later, but George had a further opportunity to deputise when Everton travelled to Leyton Orient, managed by Johnny Carey. It was a disappointing day for the Portite and Everton and they were humbled 3-0. Mike Charters observed of George: ‘He never approached the excellence of his game against Sheffield Wednesday.’

So, George returned to the Central League side and bided his time. He got to watch the first team in its pomp, when not on reserve-team duties. He greatly admired Roy Vernon and Alex Young, telling me: “Taffy was a character and a bloody good footballer. He was hard on the field, didn’t show any nerves, and was captain of the ship when we won the League. In that role, he didn’t hesitate to give you a royal bollocking when you needed one, but then that was it. There would not have been an Alex Young but for him – they complimented each other in a breath-taking partnership. Watching them together was like poetry in motion – it was bloody marvellous.”

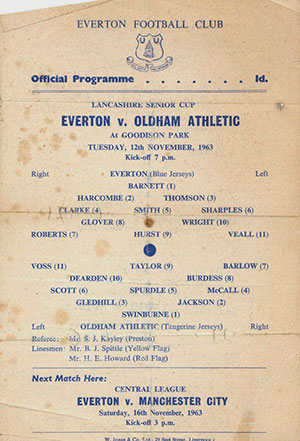

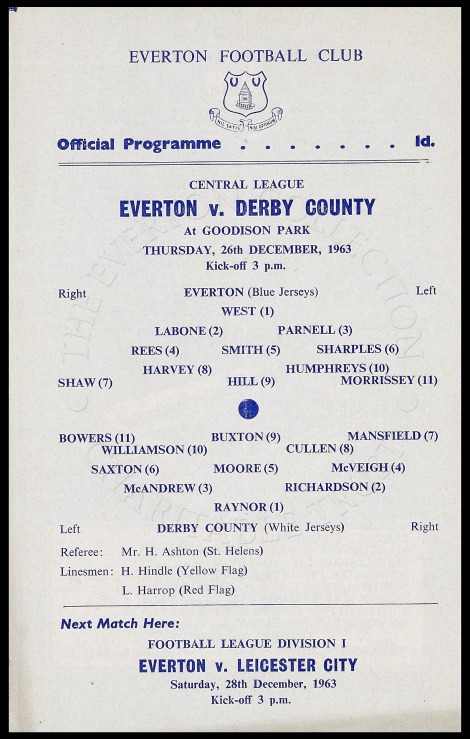

He’d be called upon for first-team duty on three further occasions, all in the 1963-64 season. His 11th and final Toffees appearance came at left-half in a weakened team which was defeated 6-0 at Highbury in December 1963.

So why didn’t George progress as well as first expected?

He was probably too laid-back and, by his own admission, enjoyed his life off the pitch maybe a little too much. He was a good pal of fellow Portite, Dave Hickson – it’s unclear which led the other astray more. George was always getting Everton players to come over to Ellesmere Port and play in various cricket or football games. George’s cousin, Les Aston, recalls Brian Harris and Dave Hickson being two regulars – George’s older brother, Bryan, was another to appear.

The other factor holding him back was that the sport was becoming faster; George was ill-equipped to cope. This is something that Derek Temple picked up on when looking back with fondness at his ex-teammate:

“I liked George – he was a smashing lad. He was popular at the club and we’d have some laughs. He was a big strong lad and looked as though he was going to be something special. He had a lot going for him. Going forward, he could strike a good ball, he could also pass and hit a long ball accurately. But the one thing he lacked was pace – as he was heavily built. That was a great shame. If the game had been played at a slower pace, he’d have been brilliant – but, if a player went past him, he could never catch him.”

Temple also recalls how George’s easy-going nature might amuse club-mates but frustrated the highly-driven team manager:

“In the main stand, there was a spiral staircase that led up to the billiards room and the dining room. There was a room off that – known as ‘the bollocking room’ – where you went on the Monday after a match. After one reserve match, in which we hadn’t played well, Harry Catterick came in with a face like thunder, having read the report on the players. Like many managers, he’d play players off each other in order to set it all off. Eventually, he came to George and said, “What about you, George? What do you think?” And George replied, “Why can’t we all be friends?” I think Harry gave up after that!” As Les Aston recalls of George, “There wasn’t an ounce of malice in him.”

With little hope of dislodging Jimmy Gabriel, Brian Harris, or (before his ban) Tony Kay from the first team, George turned down terms offered in the summer of 1964. He was expected to join Rotherham, who had agreed a fee with Everton. Instead, in March 1965, he moved to East Lancashire – going the opposite direction to the likes of Roy Vernon and Fred Pickering by joining Blackburn Rovers – then of the First Division.

Replacing Michael McGrath, the experienced Irish international left-half, George debuted in a 4-0 defeat of West Ham Utd at Ewood Park. It was the first of 113 appearances for Rovers over 5 years. Fred Cumpstey, a Rover’s supporter in that era, reflected: “George did a decent job for Rovers after his arrival. He was not in the class of Ronnie Clayton, Matt Woods or Michael McGrath but he was always honest in his performances.”

Living in Feniscowles, and not knowing anyone in the town, he was taken under the wing of Rovers’ star forward, Bryan Douglas. He told me: “As he didn’t know anybody in Blackburn, I befriended him to help him to settle in – and we remained friends the whole time he was here. He was a great lad, a smashing person, but he never really fulfilled his potential. He could play a bit – but maybe never gave it 100% and sometimes I used to play hell with him!”

In 1966, George married Carol Eddy, a strong-willed woman who helped him to curb some of his socialising and probably helped his playing career in the process. They set up home in the Pleasington district of the town. She would get employment at the Star Paper Mill in the town (George himself would work for the company after stopping playing – as did Bryan Douglas).

Les Aston remarked on how quickly George’s accent morphed from Wirral to thick East Lancashire. He had a head-start as his parents hailed from Burnley, prior to relocating to Ellesmere Port, so he had grown up surrounded by the accent. Occasionally, he would give a lift to or from Frodsham to fellow Rover and ex-Evertonian, Gary Coxon. Gary recalls that George’s continuing penchant for donning tweed outfits earned him the nickname ‘The Squire’ at Rovers.

Although briefly transfer-listed, when dropped in September 1966, he fought his way back into the team. His Rovers career came to an abrupt end as a result of a broken leg sustained on 1 March 1969 in a challenge with Dave Mackay. He saw out his career with Southport FC – the haunt of many an ex-Everton player. He made 25 appearances in Division Four during the 1971-72 season to bring his playing days to an end. He made 25 appearances in Division Four during the 1971-72 season to bring his playing days to an end. His post-football sporting activity would be bowls – often playing with Fred Pickering and Bryan Douglas in Blackburn.

George and Carol had a holiday static caravan in Cumbria and, after 25 years in Blackburn, decided to buy a house and live near Grange-over-Sands. George was predeceased by his wife in 2008. He lost interest in football in recent years but, for me, it’s a shame that he was not at Goodison Park in 2013 to take to the pitch and share in the adulation with Messrs Kay, Temple, Meagan, Bingham and Young as they marked 50 years since the League Championship triumph.

Derek Temple did catch up with George several years ago, and the FA Cup-winning forward was touched when told that he was the finest volleyer of a ball that George had seen. Derek recalls, “He said, ‘If you are ever up my way, go in the Cavendish Hotel as I’m often in there.’ I never did get up there, which is a shame as I liked him a lot.”

In recent months, George lived with esophageal cancer. He dealt with it stoically, telling his cousin over the phone: “I’ve had a good time – a good life.”

Rest in peace, George.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks to Les Aston, Steve Corley, Gary Coxon, Fred Cumpstey, Bryan Douglas, Frank Keegan, Michael McGrath, Mick Meagan and Derek Temple for their assistance.

Sources:

Liverpool Echo

Liverpool Daily Post

Daily Mirror

bluecorrespondent.co.uk

evertoncollection.org.uk

Images are taken from the Sharples family and Rob Sawyer collections