Jim Keoghan

Everton v Leeds United

Football League Division One, 7 November 1964

Everton 0

Rankin, Labone, Brown, Gabriel, Rees, Morrissey, Temple, Pickering, Vernon, Young, Stevens

Leeds United 1 (Bell)

Sprake, Reaney, Bell, Bremner, Charlton, Hunter, Giles, Storrie, Belfitt, Collins, Johanneson

To the modern fan, one reared on a game where crowds are often dispassionate tourists, players overly protected, and referees the agents of the authorities’ aims to make football as bloodless as possible; the past must look like a foreign country.

The days of swaying crowds seething with a palpable sense of malign fury, defenders who would soften forwards up with a vicious tackle to ‘let them know they’re there’, and officials who seemed to be more generous in their definition of what defined the word ‘contact’ in the term ‘contact sport’ are long gone (at least in the higher reaches of football).

For good or ill, the game has changed. But we still have our memories. Memories of times when the passion of the game crossed a line and in doing so produced something that if not beautiful, then certainly memorable. And often, such memories seem to include Leeds United.

In the mid 1960s, Leeds were on the rise. Under the management of Don Revie, the Yorkshiremen had just climbed out of the Second Division and were on the way to becoming one of the dominant football forces of the decade. Although undoubtedly blessed with talented players, such as Bobby Collins, Johnny Giles and Billy Bremner they were also a side that was developing a reputation for aggression.

The FA had labelled Leeds ‘the dirtiest side in the country’, pointing to evidence that cited them as having the worst record in the Football League for players being cautioned, censured, fined or suspended.

Jack Charlton provided a revealing insight into the Elland Road approach in his eponymous titled autobiography. In a telling account he relates a story in which the young Leeds midfielder, Jimmy Lumsden, while receiving physio treatment, had told Charlton and Revie how in a recent reserve match he had gone in with excessive force during a challenge, injuring his opponent in the process. According to Charlton, Revie had ‘murmured approvingly.’

Despite United’s refutation that they were a dirty side, there remained a perception that the FA had got it right. As a result, whenever Leeds played there was a sense that opposition teams took to the pitch expecting and preparing for a fight.

This had certainly been the case when Everton had met Leeds in the FA Cup in January 1963 at Elland Road, a bad-tempered and fractious 1-1 draw that had reflected poorly on both sides. Leeds had set the ball rolling with some vicious fouls and then Everton had responded in kind, both sides ratcheting up the aggression as the match progressed.

When the teams met nearly a year later, it seemed that memories of that FA Cup clash were fresh in the minds of those both watching and on the pitch.

The game had barely begun before the tackles started flying in. Fred Pickering was clattered by Billy Bremner. Seconds later, Jack Charlton suffered a similar fate at the hands of Jimmy Gabriel. Battle lines had been drawn.

But the Battle of Goodison, as the game subsequently became known, really burst into flames on the four minute mark when Johnny Giles, notorious among opponents for going over the top of the ball, left his stud marks on the chest of Sandy Brown, tearing his shirt in the process.

‘I was stood in the Boys Pen and watched as Brown took his revenge, catching Giles with a good left hook that floored him’ remembers Stan Osborne, one-time Everton apprentice and the author of Making the Grade, a memoir about his time with the club and his life as an Evertonian.

Brown received his marching orders and the Goodison crowd roared in protest. It was a decision that coloured all that followed.

‘Leeds were rough but after a while it almost didn’t matter. Every tackle they made, clean or not, was met with fury by us’, Osborne recalls.

When it came to agression on the pitch, Everton might have being missing their very own ‘hard man’ in Tony Kay, but the Blues still had enough available to meet Leeds kick-for-kick:

‘We had the likes of Jimmy Gabriel, Johnny Morrissey and Dennis Stevens to give the likes of Norman Hunter, Jack Charlton and Billy Bremner, a run for their money’ remembers Kay.

Harry Catterick was the kind of manager who wasn’t afraid to mix it up. The addition of more bite to the squad was one of the things that set Catterick apart from his predecessor, Johnny Carey.

‘I remember watching the tackles raining in and with half an hour gone it was almost a surprise that Sandy Brown was the only player sent for an early bath!’ recalls Stan Osborne.

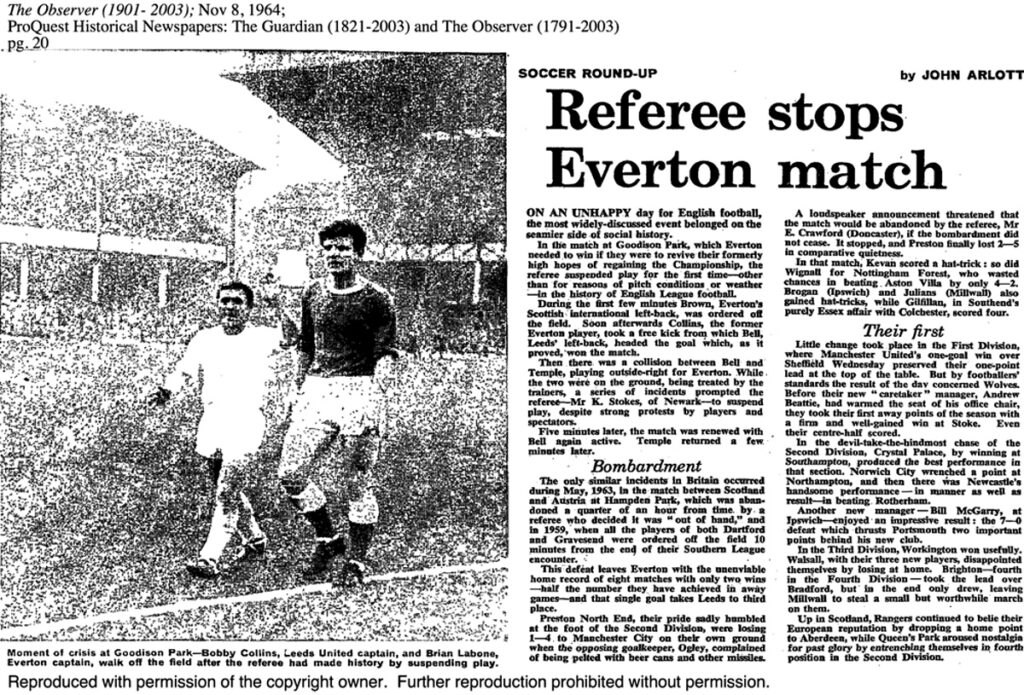

The tipping point, and the moment when the game passed into infamy, occurred ten minutes before the break when Leeds full-back, Willie Bell launched a two-footed tackle at Derek Temple. The Everton outside left was knocked unconscious. The crowd seethed in response. Missiles hurled down onto the pitch, Leeds players were spat at, intermittent fights broke out (on and off the pitch). Such was the level of hostility, the referee marched both teams off the pitch so that the players and fans could cool down. It was the first time that had ever happened in an English league game.

‘I was stretchered off and was lying in the dressing room, when all the players came in after he’d (Referee) told them to go off. I heard him talking to the two managers, saying “I’m calling the game off. There is going to be a riot out there”. Both managers said there will be a riot out there if you don’t get those players out on that pitch!’ recalls Temple.

The referee lectured the players during the halt in proceedings, entering each dressing room and telling the teams that if their behaviour didn’t improve they would be reported to the FA.

Outside, for a time, nobody knew whether the game had been suspended or abandoned. Eventually, after five minutes, it was announced on the loudspeakers that play would soon restart, although the fans were warned that the match would be abandoned if more missiles were thrown at the players.

Ten-minutes after they had been trouped off, the players returned to a pitch partially strewn with the detritus thrown from the crowd. Temple and Bell (the latter had hurt himself during his disgusting challenge) came back too.

But despite the referee’s warnings little really changed. Some of the tackling, specifically by Norman Hunter and Roy Vernon, remained exceptionally aggressive and the game seemed to be powered by an undercurrent of venom and animosity.

Hunter was booked, and Bremner, Collins and Vernon warned for dangerous play. Astonishingly, no further players were sent off. Perhaps the referee didn’t want to risk antagonizing the crowd any further.

Somewhere along the way, Leeds managed to make the most of their extra man and go ahead, the goal coming courtesy of Bell (which hardly helped the mood of a crowd who believed that he shouldn’t even be on the pitch). In response, Everton refused to lie down and despite their numeric disadvantage went on the hunt for an equalizer, with Leeds grimly holding on to the end for their victory.

Throughout the entire game, the kicks and fouls barely relented; ending with nineteen transgressions inflicted by Everton and twelve by Leeds.

‘And in response, the hostility that seethed through the crowd continued. It was so bad that after the game, there were mounted police outside to disperse us. It was the first time I had ever seen that at Goodison’ remembers Stan Osborne.

Unsurprisingly, the press reacted negatively to what had happened. This ‘unhappy day for English football’ was labelled by the Sunday papers as ‘vicious’ and ‘spine-chilling’. Blame for what occurred was apportioned equally, with the players, the fans and the referee castigated for the role they played.

Inevitably, the FA responded to what had happened. Evertonians can probably guess what occurred next. When the FA disciplinary committee met on 9 December 1964 it suspended Sandy Brown for two weeks and fined Everton £250 for the behaviour of their fans. Revie’s men emerged unscathed.

Irrespective of their darker side, Revie’s men could play and over the following decade were never out of the top four (an achievement the would not have been possible via brute force alone, as Wimbledon would later prove).

Certainly, John Moores wasn’t put off by the Battle of Goodison. Years later, prior to Harry Catterick’s elevation to the board, the newspapers were filled with rumours that Revie had been offered a record-breaking annual salary plus a massive signing-on bonus in an attempt to lure him to Goodison.

The deal never came off. Revie opted to turn down Everton’s offer of £25,000 per year and stay at Leeds, citing ‘personal reasons’ for his decision. But for a time, the move had been on. There was a moment, however brief, when the School of Science was close to metamorphosing into the School of Hard Knocks.

Footnotes

Steve Johnson, Evertonresults.com

Wikipedia, List of Leeds United F.C seasons

The Independent, Bobby Collins, Obituary

Jack Charlton, The Autobiography, Corgi (6 Aug 2020)

www.theguardian.com, Everton v Leeds 1964 from the archive

bluekipper.com, Interview with Derek Temple

www.dixies60.com, Games that shook Goodison; Everton v Leeds – The Battle of Goodison

Stan Osborne, Making the Grade (1970)