Rob Sawyer appears on French TV

Recently, Heritage Society member Rob Sawyer appeared on the French TV channel ARTE, to tell the story of the origin of goal nets. It’s an enjoyable film put together by our gallic visitors, capturing some great shots around Goodison, as well as the surrounding area. Unfortunately, there are no subtitles, but if your French skills aren’t quite up to the job, Rob’s fascinating article telling the full tale appears below. (click the image to watch the video)

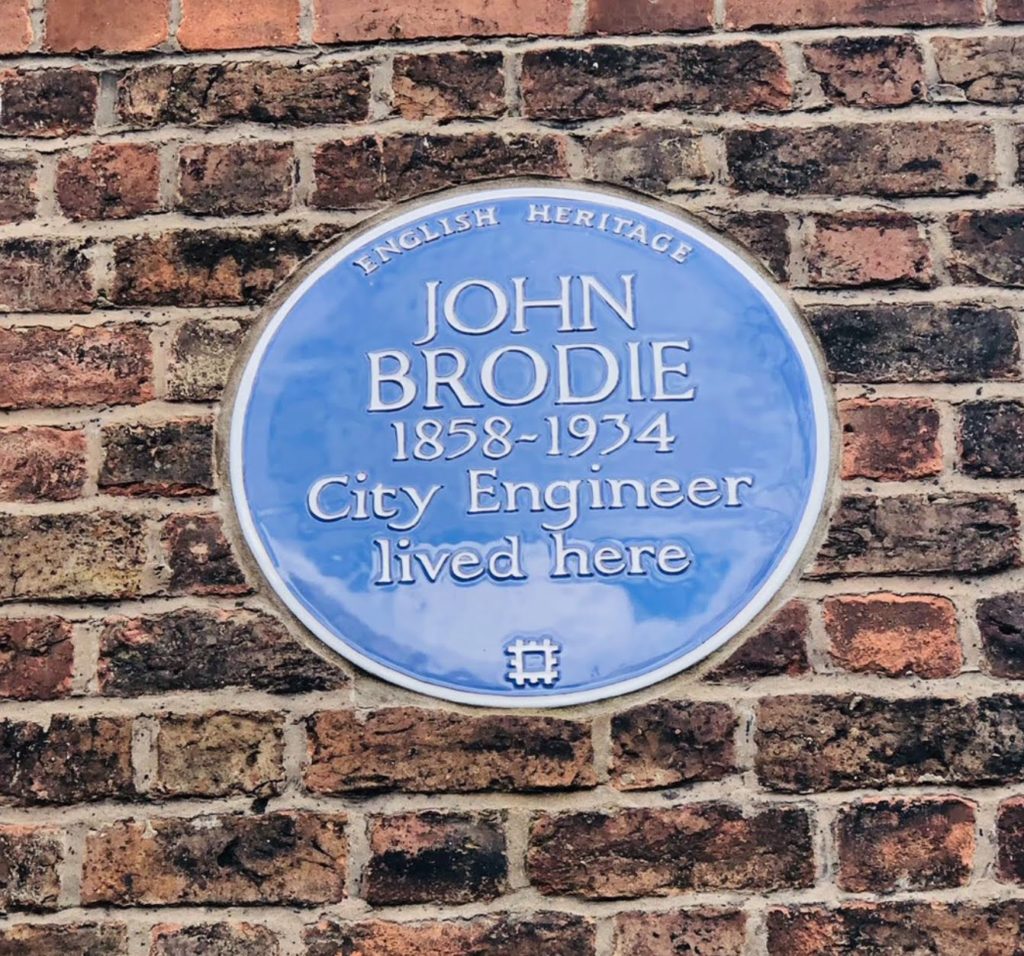

Net Gains: John Alexander Brodie’s Sporting and Civic Legacy

Rob Sawyer

The rustle of the net as an exocet-like shot beats the goalkeeper all-ends-up – it’s one of the visceral thrills of watching football. The man we have to thank for goal nets – the simple, yet vital piece of sporting equipment – is John Alexander Brodie, who was born in Bridgnorth, Shropshire, on 1 June 1858. He was one of six children born to Scottish parents James and Elizabeth.

Young John spent his childhood in both the north of Ireland and Scotland. He began his working career on Merseyside, apprenticed in 1875 to the chief engineer of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board. A scholarship took John to Owens College, Manchester, and he received training at the offices of Sir Joseph Whitworth. After completing his studies he returned to Liverpool as a temporary assistant in the city engineer’s office. He then went to Spain (near Bilbao), where he spent two years on harbour engineering work, before returning to Liverpool where he was employed for eight years in the Corporation Engineering Department. Then, in 1892, he set up in private practice as a consulting engineer, as partner to Mr J. Wood.

John’s interests outside work included golf, country sports (fishing and shooting) and Rugby Union, which he played to a fair standard on Merseyside with Old Boys. He also seems to have taken an interest in the Association code of football in his adopted city. It is said that he was in the crowd at Anfield on 26 October 1889, when Everton took on Accrington in a Football League match. The encounter ended all square, 2-2, but Everton protested that they should have been the victors, having had a goal disallowed in the most controversial of circumstances. Brodie saw the umpire/referee wrongly disallow Alex Latta’s effort from an acute angle, as he wasn’t convinced that the ball had actually passed between the posts. Here is how the Liverpool Courier described the events on the pitch:

With a goal against them, the home lads played up with more determination and Latta from a position almost parallel with the goal posts, kicked the ball splendidly, a great cheer being sent up by the crowd. The referee however ruled that the ball had not gone through and he was promptly and vigorously hooted.

The decisions of Mr J.J. Bentley at this point roused the ire of the crowd, and there were loud cries of disapprobation, which were certainly not justified.

The incident was far from unique; indeed, the Toffees had benefited from a similar officiating error when closing in on a first Football League title in January 1891. The 4-2 win over Notts County was remembered by Toffees forward Hope Robertson for a supreme piece of gamesmanship by teammate Dan Doyle:

The game at one period was going in favour of the Notts team, and with a grand finish to a prolonged attack James Oswald scored a splendid goal. I was quite near to him when he let go the shot which fairly beat our goalkeeper. Naturally, I turned and walked down the field with Oswald, at the same time congratulating him on his splendid effort, which brought his side on level terms with us.

Now, this is where Doyle’s bluff beat the referee. I may explain that the shot from Oswald’s foot was swift and low, travelling from left to right, and went through close to the ground and near to the goal-post. There were no nets in those days to stop the ball when a goal was scored, and Daniel went after the ball, walked calmly with it to the bye kick-off line, placed it, walked back, and with a wave of his hand to be ready he ran out and kicked off the ball. While carrying out this little bit of bluff, Dan’s face assumed a look of simplicity which would have deceived old Father O’Flynn himself. At any rate, his bluff beat a referee, who thought himself one of the smartest knights of the whistle in England.

But James Oswald was not deceived. He appealed, he explained, he swore, and for a moment I thought Jamie was going to strike the referee, but he pulled himself up, and, with a look of utter disgust at the referee, he turned and went into the game with greater determination than before. Had that goal been allowed – as it ought to have been – it would be hard to say which team would have won.

Of course, the sport was still evolving, with the width of a goal (eight yards) only formalised in 1863. Even then, the presence of a crossbar was not standardised. Some clubs used a string or tape but others had no physical height-limiter – so ridiculously high shooting attempts could be claimed as goals. Only in 1882 did a crossbar, at eight feet above the ground, become mandatory – but there was no form of ball retainer to catch a ball once it has crossed the goal line. The lack of a net also made it possible for vociferous spectators to crowd the opposing goalkeeper – as was the case in a Bootle vs. Everton derby in the Liverpool Cup competition in October 1886. Early on the Bootle umpire, with great honesty, would not allow his side’s goal claims to stand, as he adjudged the ball to have passed the wrong side of the post. Then matters hotted up as described by ‘Rambler’ in The Football Field publication,

There was nothing done in the scoring line until about twenty minutes had elapsed. Briscoe was stood offside, but the [Bootle] goalkeeper, whose nerves would doubtless be a little upset with the yelling of the small boys who got as near him as they could, let the ball drop, put Briscoe on side, and the little Evertonian, who was the best forward on the field, lost no time in registering number one.

The reporter described events escalating in the second period:

The Bootle captain spurred his men on for a final effort, but a minute and a half from time the ball hit the spectators, and the play going on the referee blew his whistle.

The company present evidently thought this was the finish, for they rushed on the ground, and further proceedings were delightfully mixed up. The playing portion was covered with the spectators, and the combatants were squandered up and down. Mr. Bentley, the referee, was appealed to as to what should be done, and after asking the Bootle captain if he wished to play the minute and a half, to which that gentleman responded ‘Certainly’, he said they must play.

But what about clearing the field? Well, the referee had nothing to do with that, it would have to be cleared before they could play. However, this was an impossibility, and the players were chaired off to the pavilion, where several excited arguments were indulged in. At length, Dobson took his men on the ground again, but Bootle were partially undressed and declined to follow.

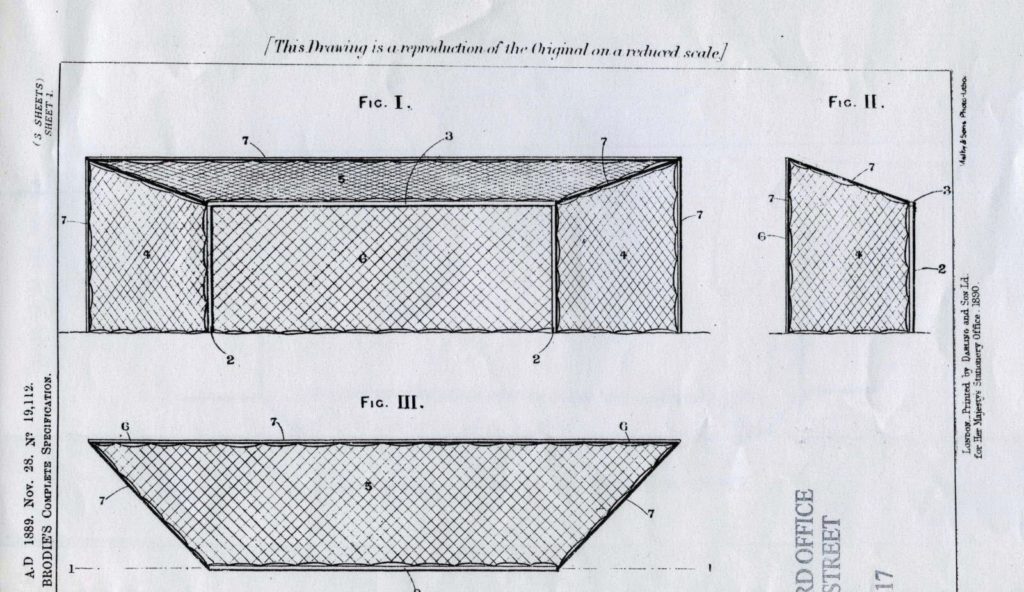

Back to October 1889: complaints about the disallowed Latta goal against Accrington rumbled on in readers’ letters in local newspapers – with the match official’s eyesight being called into question. John was inspired to put his agile mind to finding a solution that would prevent further controversies (it should be noted that it has been said that Brodie was already working on a goal net concept in August, two months before the Everton-Accrington encounter). He came up with the concept of a ‘pocket’ behind the posts and (perhaps inspired by his love of fishing) considered netting as the best option – rather than canvas or boards – as it permitted good visibility for spectators. His early designs incorporated bells that would ring as the ball struck the netting. He submitted a patent design remarkably quickly, on 28 November 1889. Although John took credit for the design (the patent for a slightly revised version was approved in November 1890), a Daily Post article some years later claimed that it was a collaborative effort between John and his older brother, William, who was assistant engineer to the Mersey Harbour Board. Why William, who lived on the Wirral, sought no public credit is not known.

The nets were first tried out in local matches at Stanley Park. It has been written that they were given an outing in Bolton when the Trotters played Nottingham Forest on 1 January 1891 – but I can find no contemporary reference to this. They were first deployed for a high-profile fixture on 10 January 1891 – a North vs. South international selection game in Nottingham. Fittingly, Fred Geary (an Everton player – who hailed from Nottingham) scored the first goal, with fellow Toffeeman Edgar Chadwick also ‘netting’.

The Liverpool Mercury reported:

BRODIE NETS ON TRIAL

The goal nets, introduced by Mr. J.A. Brodie of Liverpool, were used, and were considered by the goalkeeper a very useful introduction.

With the goal nets having proved their value, Everton trialled the innovative solution three weeks later at Anfield, when Bolton Wanderers fulfilled a friendly fixture. ‘Loiterer’ of Athletic News commented: Mr. Brodie’s net was up, and it looks a good invention. If it is generally used it will prevent a lot of unsatisfactory decisions by referees.

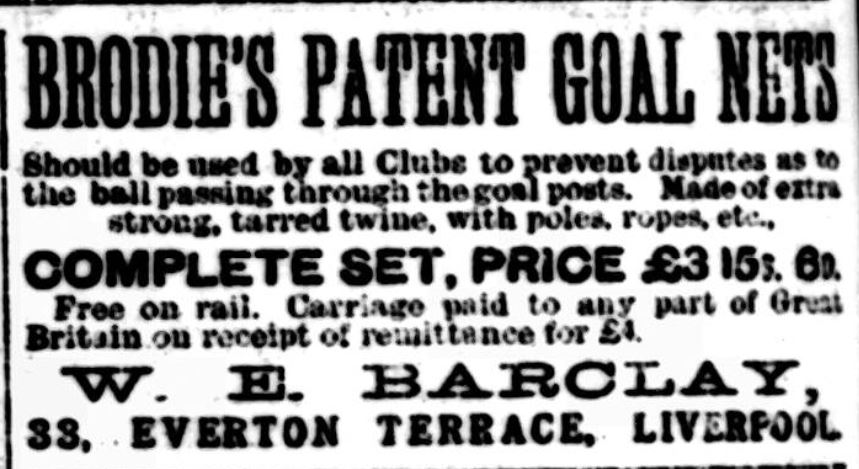

Suitably impressed, the club’s administrators approved the purchase of a set on 9 February. Before long other clubs followed suit and, from 1 November 1891 it was confirmed that they were to be used in all Football League matches. Advertisements for the ‘Brodie’s Patent’ nets were soon commonplace in newspapers across the land. The first FA Cup final to use goal nets was reported to be the 1892 final, played in London at Kennington Oval, between West Bromwich Albion and Aston Villa (although there is evidence that they may have debuted at the same venue a year earlier).

Although this invention might have been enough for the average person, John Brodie’s influence on Merseyside and beyond was far greater. In 1898 he was chosen ahead of many applicants as the Liverpool City Engineer – a post he held for 27 years, during which he was responsible for schemes costing over 13 millions pounds (he had to give up his pecuniary interest in the goal nets, on accepting the role).

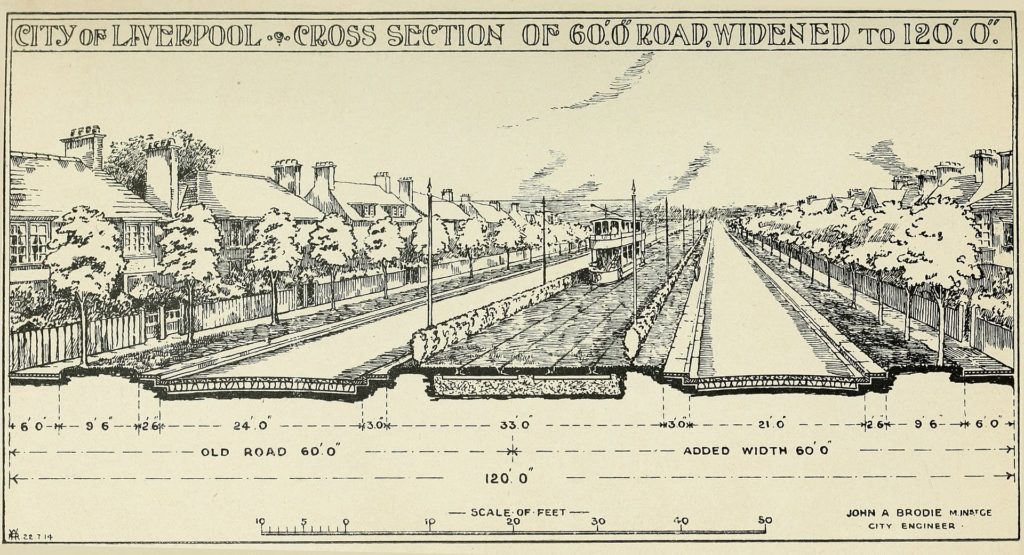

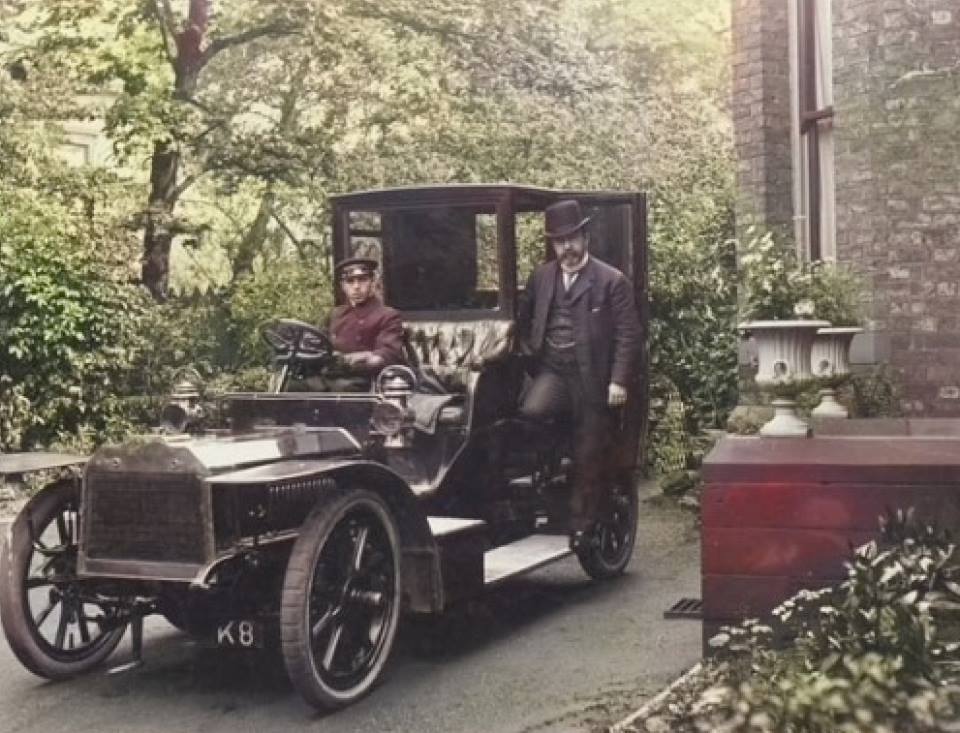

First and foremost, Brodie was a town-planner of vision. He foresaw the growth of the motor car and bus as a method of transport, playing a leading role in the formation of the Liverpool branch of the Self-propelled Traffic Association in 1896. He visualised great roadways which would not only serve for speedy means of transport, but would also provide the citizens with leafy promenades. In the face of considerable opposition he created the pioneering Queen’s Drive by revamping fairly modest council plans to widen Walton Village and Cherry Lane. The result was a wide dual-carriageway ring-road route, skirting the city from Walton to Mossley Hill. He then set about creating impressive radial offshoot routes such as Edge Lane and Walton Hall Avenue.

with a central segregated tram track in Liverpool (1914)

(Aigburth Cricket Club is now on the land to the bottom right)

Other notable achievements are listed below (not exhaustive) :

- Liverpool’s order for the first municipal motor-lorry.

- Responsible for providing the tracks for the electric tramways.

- Significant sewer system improvements in Walton

- In 1912 he was appointed the engineering member of a commission which set out to plan New Delhi (19 years later visiting the city as a special guest)

- During the First World War he was responsible for turning the North Haymarket, Liverpool, into a great munitions depot

- He was the first to suggest a road directly linking Liverpool and Manchester – what became the East Lancs Road (an extension of Walton Hall Avenue)

Few committeemen cared, or dared, to disagree with John – nearly everyone was content to say ‘Leave it to Brodie.’ He did most of his thinking in bed, from 5 until 7 in the morning – when he felt his mind was clearest for contemplating the pros and cons of potential projects, before going in to do more routine work during his normal office hours. Failures were few and far between, but experiments in cost-efficient prefabricated concrete housing construction were not deemed an unreserved success (but they did influence others). Also, ambitious ideas to build a road tunnel under the Everton district and develop a bridge linking the Wirral peninsula, near Hilbre, with North Wales – did not come to pass.

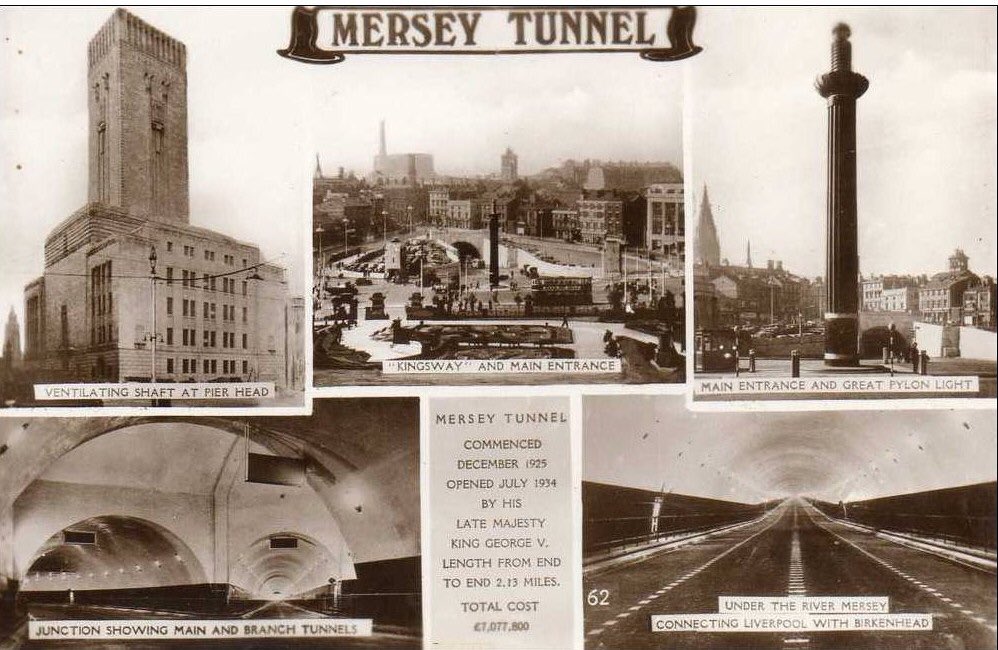

Brodie received many tributes from his professional colleagues, and was the first municipal engineer to become President of the Institute of Civil Engineers. For many years he was Associate Professor of Engineering at Liverpool University. In 1925 he resigned as City Engineer to focus on his role as joint-engineer of the first road tunnel under the River Mersey.

Mersey Tunnel

He worked jointly with Sir Basil Mott, the project taking nine years to connect Liverpool with Birkenhead under the Mersey. It was completed just a few months before Brodie’s death in July 1934, and at the time it was the world’s longest underwater road tunnel (and remained so for twenty-four years). It is one of the largest municipal construction projects carried out in the UK, and is regarded as Brodie’s greatest engineering achievement.

Otterspool Promenade

In 1919, John Brodie reported to the City Corporation that the river-front from Fulwood Park to Garston was suitable for the development of a riverside promenade which could include facilities such as open parkland, tennis courts, bowling greens, swimming and boating pools, and various other pastimes.

According to Mike Royden,

Brodie began to devise a scheme to enclose 43 acres of foreshore from Dingle Point to Garston Docks by the construction of a river wall and the land to be reclaimed by the controlled dumping of clean household refuse. In fact, no action was taken at that time, but in 1925 the Corporation was requested by the Mersey Tunnel Joint Committee to allow material excavated from the new Tunnel to be tipped on the Otterspool Foreshore. Consequently, the City Engineer was instructed to prepare a suitable scheme and to suggest arrangements for reclaiming the area. Provision of a promenade fronting the river was also part of his brief. In 1928-29 schemes for the construction of a river wall and embankments were submitted to the City Council by Mr. T. Peirson Frank, Brodie’s successor. Tipping commenced in September 1929, and the construction of the river wall began in July of the following year and completed in 1932. The void created behind it was filled with domestic refuse. This new, although temporary, ‘tip’ proved to be a huge economic success, as the disposal of this waste matter dealt with the bulk of Liverpool’s requirements up to July 1949. Approximately two million tons were disposed of, and the saving in cost of incineration more than offset the original cost of the construction of the river wall and embankments, and the even the layout of the promenade, paths, and open spaces. The Riverside Promenade was opened to the public on 7 July 1950

Mike Royden, A History of Otterspool – www.roydenhistory.co.uk

This project may have been completed sixteen years after his passing, but this was clearly Brodie’s vision, and an engineering masterstroke.

with his aircraft in France

In 1897, John Brodie had married his Scottish cousin, Amelia (Aimee) and went on to have two daughters and two sons (Freda, Aimee, John and Eric). Eldest son Eric had attended Greenbank School and Shrewsbury School, and was expected to follow his father into engineering. However, the war intervened and he was commissioned into the RFC (which became the RAF) and flew sorties over France during the conflict. Wounded, he returned home, but resumed duties late in 1918. Serving with the occupying forces, his aircraft crashed with fatal consequences near Cologne on 11 February 1919. Lieutenant Brodie was just 20.

John Brodie lived with diabetes and died in his sleep at home at Aigburth Hall, on 16 November 1934. He was seventy-six. The funeral at Anfield Crematorium was preceded by a service held at the city’s cathedral. It was attended by many representatives of the engineering profession, Liverpool Corporation officials, members of the engineering faculty of the Liverpool University, and many friends. Tributes flooded in, with one contemporary describing him as a ‘second [Thomas] Telford’. Amelia went on to sell Aigburth Hall and saw out her later years in Wiltshire.

Aigburth Hall was demolished and both the facing Aigburth Road and lower section of Aigburth Hall Avenue were widened, ironically as part of the boulevard scheme first devised by Brodie.

Finally, you might wonder if John Brodie was an actual Evertonian – or just an interested spectator at Anfield, on that day in 1889? This was never made clear in reports, but his attendance at our then home, witnessing a disallowed goal, helped to shape the game we love. In spite of his stellar career in urban planning and engineering, John Alexander Brodie was said to look back with most fondness on his sporting invention.

Acknowledgements/Sources

Eileen Brodie

Dorian Clotard/Arte

Liverpool Post and Mercury

Liverpool Daily Post

Liverpool Echo

Everton Chronicles – Bluecorrespondent.co.uk (Billy Smith)

The Everton Collection – Evertoncollection.org.uk

Keith Jones, Liverpool Then and Now (Twitter account)

Ray Physick, Played in Liverpool: Charting the heritage of a city at play: No. 4 (2007) ( – Historic England)

Rob Sawyer, The Hope Robertson Chronicles (2022)

Congratulations! Wonderful piece..

I am a great grandson of John Alexander Brodie. His daughter Aimee Ross Brodie was my grandmother.

Many thanks Richard, an enviable ancestry!

A very enjoyable article. Liverpool Rambler claim, in their history, that they first tried out the nets for Brodie. The initial version had bells attached .. the idea being that they would ring when the ball hit the net. They did not ring! and were therefore dispensed with.

Interesting facts Brian, many thanks!