Chedgzoy is a brilliant raider, a clean player and a companiable man.

Athletic News – 1921

Rob Sawyer

In 1924, Samuel Chedgzoy wrote himself into the annals of football history for his role in forcing a hasty change to the rules of the sport. This stunt (more of which later) was but a small part of the remarkable, and sometimes intriguing, life of one of Everton and England’s finest outside rights – and, alongside Joe Mercer and Stan Cullis, one of Ellesmere Port’s greatest sons.

The surname has a slightly exotic feel – Eastern European maybe? The truth is more prosaic. The Chedzoy family hailed from Somerset. When Annie Chedzoy married her cousin Joseph Chedzoy, they erroneously signed the register with G in the name. They decided that they liked the look of the new spelling – so Chedgzoy stuck in that branch of the family.

Sam’s father, Henry – married to Frances – was a galvanised labourer who had moved to the Wirral from Bridgewater. Samuel, the fifth of nine children, was born on 27 January 1889. By 1891 the family was residing at 91 Worcester Street in the Whitby district of Ellesmere Port . Sam married Annie Ferrington in 1910 (he was listed in the 1911 census staying at the in-laws at 15 Walton Lane, Kirkdale). Late that same year, his performances for Burnells Iron Works football team in the West Cheshire League (Second Division) – where he had Joe Mercer Sr. as a clubmate – caught the attention of Everton’s secretary, Will Cuff. Cuff later claimed to have immediately spotted the winger’s potential to become an international-class forward. He was duly signed for a £10 transfer fee, rising to £25, on a £2 weekly wage.

Within a month of joining the Blues, he was called up to the first team in place of Arthur Berry for the Boxing Day fixture – a 1-0 defeat to Newcastle United. He was selected twice more that season – two victories, then had an extended period in the reserves. His next senior outing came in January 1913. Back in the team in the autumn of 1914, he sustained a broken pelvis when a Bolton Wanders player fell onto him – he returned ahead of schedule at the end of March. Fully fit, Sam started the 1914/15 season as the first-choice right winger, missing just eight of 43 possible appearances. This, of course, was a season of glory, but the League Championship win was overshadowed by the declaration of war against Germany in July 1914. Sam’s ability to run down the wing at pace and deliver deep, accurate, crosses without breaking his stride served centre-forward Bobby Parker well. With George Harrison delivering high-quality crosses for the other flank, the Scot was in clover – scoring 35 times, at a strike rate of a goal per game.

With regular football halted in the summer of 1915, Sam was living at 101 Robson Street, and employed as a fitter’s labourer at Harland & Wolf shipbuilders, prior to enlisting with the Scot’s Guards in December of that year, under the Derby Scheme. Trained at Caterham in South London, he played guested for West Ham in the 1916/17 season. A knee injury sustained in April 1917, when playing for his battalion team, resulted in six weeks of hospitalisation – and a chance encounter he recalled with a fellow footballer: ‘I was removed from Millbank Hospital to Mitcham, and was being carried on a stretcher to the ambulance. I was placed in a top berth and the RAMC sergeant asked my name. I said “Chedgzoy” and he replied: “How do you spell it?” Then came the voice of the driver of the ambulance: “All right segreant, I’ll tell you about that.” He was Dave Turner of Burnley, then of the RAMC.’

Once fit, in August 1917, he was posted to France. Of his war years, Sam recalled: ‘George Harrison and myself served together and were members of the football team that won the divisional championship. I won two models out there but lost them. Souvenir hunters, I suppose! George was known as “Whizzbang” out there, on account of his strong shooting, and he was a terror to some goalkeepers we met. The Scots Guards had the best team in France. We beat the Belgian Army team, the side that came over to England and did so well. They had been beating all-comers out there, but we won 5-2. There were 15,000 Belgian troops present at that game, and 200 or 300 Scots Guards walked nearly nine miles to watch the match.’

Six months later he wrote to the Liverpool Echo to let readers know how he was faring on the Western Front:

‘We are having a good rest at present, and there is no doubt that our division deserves one. You will know by now how our chaps have been going through the Germans. I had a rotten job myself (I must not tell you what it was), but I hope I never get the same job again. I am back again with my battalion, and I don’t think we shall be worried for a few weeks. I see the Reds gave the Blues a rare trouncing. It was quite a surprise out here. I have had to put up with quite a lot of leg-pulling over it.

‘We played six matches during the seven days previous to the attack, all of which we won; as a matter of fact, the last two were won 6-0 and 10-0 respectively against the R.E.’s (who say they had not been beaten for over twelve months) and the Royal Berks. Yesterday we played a team picked from the RE’s, Ordnance Corps, and Garrison Artillery. We won again 3-0.

‘Paul Cooney, of Tranmere Rovers, was one of our opponents. We have not such a good team as before the attack, for we had four of our players gassed: Weir of Bolton, and Thompson, of Fulham (very badly), and George Harrison has been feeling rather bad with it, but not bad enough to get him down the line. I don’t think I shall be sent off this field for not keeping my head down!’

He wrote again to the newspaper, just prior to Christmas, stating that both he and Harrison were ‘in the pink of condition’ and stating his hope of getting a few games for Everton while on leave before the season’s end, stated: ‘I would just love another game at Goodison Park.’

He was back for the Toffees, while on army leave in December 1918, rolling back the years with his display against Burnley. It moved the Merseyside sports journalist Bee (Ernest Edwards) to write: ‘A feature of the game was the wonderfully smart work of Chedgzoy, who displayed all his. pre-war felicity of footwork.’

Demobilised on 23 October 1919 (his address was given as 65 Olney Street in Walton), Sam was able to return to Everton duties with the 1919/20 season (the first conventional one, after four years of regional competitions) already underway. The reigning champions had been ravaged by Father Time and, in the case of Bobby Parker, war wounds. George Harrison, meanwhile, bore psychological scars which would never properly heal (he took his own life in 1930). Sam, Tom Fern and Tom Fleetwood were among the few who were able to rediscover their form of old for the Toffees, but the side could do no better than a 16th place finish in a 22-team table.

Although the Blues flirted with relegation two seasons later, Sam seemed to age like a fine wine. With experience, he had eliminated the tendency to overdo things on the ball, and instead become a canny operator, week-in, week-out, on the right flank. According to the respected sports journalist, Don Kendall (writing as Pilot), Sam was: ‘A speedy winger with wonderful ball control, he was one of the first wingers to adopt the practice of cutting inside unexpectedly towards goal. He was an adept at the swerve, and one of the wiliest outside men I have ever seen.’

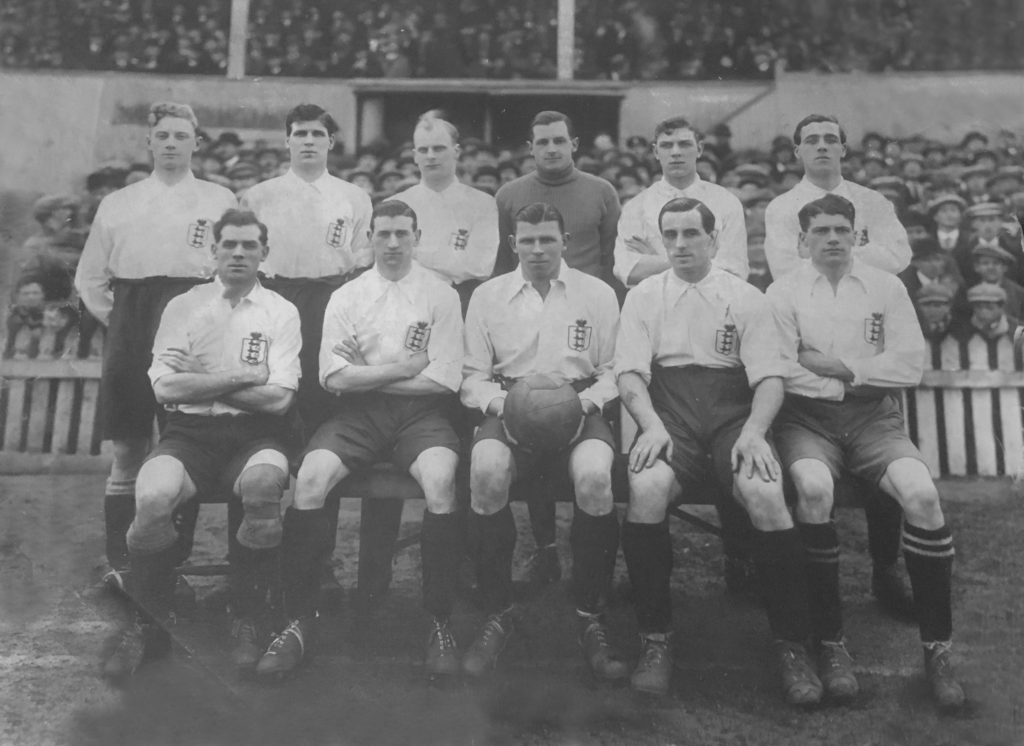

What might have been seen as the autumn of his career saw him belatedly capped by England. In 1920, at 31, he was awarded two caps – with six more selections to follow. The last came, fittingly, at Goodison Park in a 3-1 defeat of Ireland in the autumn of 1924. He failed to consistently replicate his brilliant club form at international level, but he did shine in a 1-1 draw at Windsor Park in October 1921. This was remarkable as gun-wielding British soldiers patrolled the touchline, with armed vehicles parked outside, due to the fraught political situation in Ireland.

In November 1924, Goodison Park bore witness to the feat which gave Sam enduring fame. He had been approached by Bee to highlight the fact that a player could dribble directly from a corner-kick, without contravening the rules. Liverpool player Donald McKinlay had previously agreed to the stunt, but had got cold feet and informed Bee, accordingly. Sam was game, however, and agreed to do it (for a £2 bounty) within the first 20 minutes of the match, to make the copy deadline for the Football Echo. This was easier said than done; repeatedly he tried to play the ball off the shins of the opposing full-back to earn a corner – earning some frustration from the crowd. Finally, the ploy came off. The Daily Courier described the events which unfolded at Goodison when Everton took on Arsenal:

Sam Chedgzoy drove a coach and four through the corner kick rule by adopting a course which had never before been attempted in first class football. He touched the ball forward from a corner kick more than once before putting the ball into the middle. By doing so he gained several yards. Rutherford [for Arsenal] went one better later in the game, as he dribbled the ball from the corner and took a shot at goal. The fact that the referee believed that this unorthodox way of taking flag kicks was within the rules must open up the topic whether it is in the spirit, if not in the letter of the rule, to employ such moves.

Less publicised is that on the same day as the two rule-challenging corners at Goodison, George Harrison, Sam’s old pal, had done the same thing for Preston in their match against Nottingham Forest at Deepdale. Consequently, the FA called an emergency meeting to change the law and ensure that the corner-taker could only strike the ball once.

When a fellow Wirral man joined the club in 1925, he was taken under the wing of the veteran winger. That prodigy was, of course, William Ralph Dean and the pair would have a season and a quarter together as teammates. In the 1970s, Dean described Sam to his biographer, Nick Walsh, as ‘a wonderful character…like a father to me.’ In an interview with the Liverpool Echo’s Michael Charters, the illustrious centre-forward recalled: ‘Sammy used to say to me: “When you see me going down the wing, and keeping to the line, I want you to go to the far corner of the penalty area. That will give you room to run in there, and you will find these crosses coming over for you.” And that’s exactly what they did.’

The Daily Courier’s description of Dean’s goal against Burnley on 27 February 1926 captures the partnership working at its best:

It has, however, to be recorded that Everton’s goal was one of the finest scored on the ground this season. A free kick against the stalwart Hill led up to it, the ball coming out to Chedgzoy. He darted down the wing, rounded Hughes, then beat him for speed, and whipped in a square centre in front of goal, just right for Dixie’s head, which did the needful. It was Dean’s 23rd goal of the season. In a sporting way Dean declined the ‘bouquets’ and indicated his to clubmates.

Later that same season Sam brilliantly displayed the sang-froid which came with experience. Don Kendall recounted the tale in the Echo:

When Everton visited the County at Meadow Lane, they were awarded two penalty kicks. On each occasion Iremonger – the tall Nottingham County goalkeeper – persisted in leaving his goal to change the position of the ball before the kick could be taken. Iremonger kept on arguing that the ball was not on the spot. No matter how it was placed he would leave the goal and change it. His object was, of course to unnerve Wilfred Chadwick, who was to take the kick. The result was that poor Chadwick missed both penalties.

When the County came to Goodison Park to play in the return match and Everton were awarded a penalty, Chedgzoy was not to be caught in the same way. Sammy walked over and placed the ball on the spot. Immediately, Iremonger came out of goal and began to alter the position of the ball, protesting that it was not on the spot. The laconic Chedgzoy strolled over to Iremonger and said, ‘Don’t you worry whether the ball is on the spot or not. You just get back into goal and pick this out of the net.’ Then, standing over the ball, he placed it into the corner of the net well out of Iremonger’s reach. Nothing ever upset Sammy.

Although the club did not realise it, Sam called time on his distinguished and lengthy Toffees career of 16 years and 300 appearances a few weeks after this cooly dispatched spot-kick. . Never prolific – wingers rarely were – he capped a fine farewell performance on the last day of the 1925/26 season with a goal at Burnden Park, described here by Bee in the Liverpool Football Echo:

Everton’s joy was complete when Chedgzoy, who had made a number of rousing dribbles, worked inward. Pym caught the ball, slipped up, and turned the ball just over the goal-line. Bolton were inclined to dispute the goal, but the referee was most emphatic on the point. The crowd now evaporated like snow on a fire.

The Daily Courier saw enough to be convinced that the 37-year-old was far from finished:

Chedgzoy and Dean were the outstanding forwards. Judging by Chedgzoy’s game on Saturday, he has served years football in him yet. For the end of the season, he showed a turn of speed that was astonishing. His shooting too, was well on the mark.

In late May he embarked for Canada. In 2008, a DVD was released to mark the 800th anniversary of Liverpool. Members of the Chedgzoy family were stunned to see that it included vintage footage of Sam walking up a ship’s gangplank, pausing, looking straight at the camera and then carrying on.

Unbeknownst to almost everyone, the footballer had no little intention of returning. For reasons of the heart (his personal life was complicated, at times), he decided to start afresh, far away from Merseyside. He had spent the summers of 1922 and 1922 in the territory, engaged by Brig. Gen. F.S. Meighen to coach the Grenadier Guards soccer team in Canada’s Interprovincial League – so he was familiar and taken with his surroundings. It came as a shock to Annie Chegdzoy, who had been completely in the dark as to his impending emigration. She remained in England, raising Sydney.

Also blindsided was the Everton board, which had offered their forward the maximum permitted wage to extend his Everton career by a further year. He had demurred and the Toffees directors only got wind that he would not return, in late July, when Sam intimated to an FA touring side in Canada that he might remain beyond the summer.

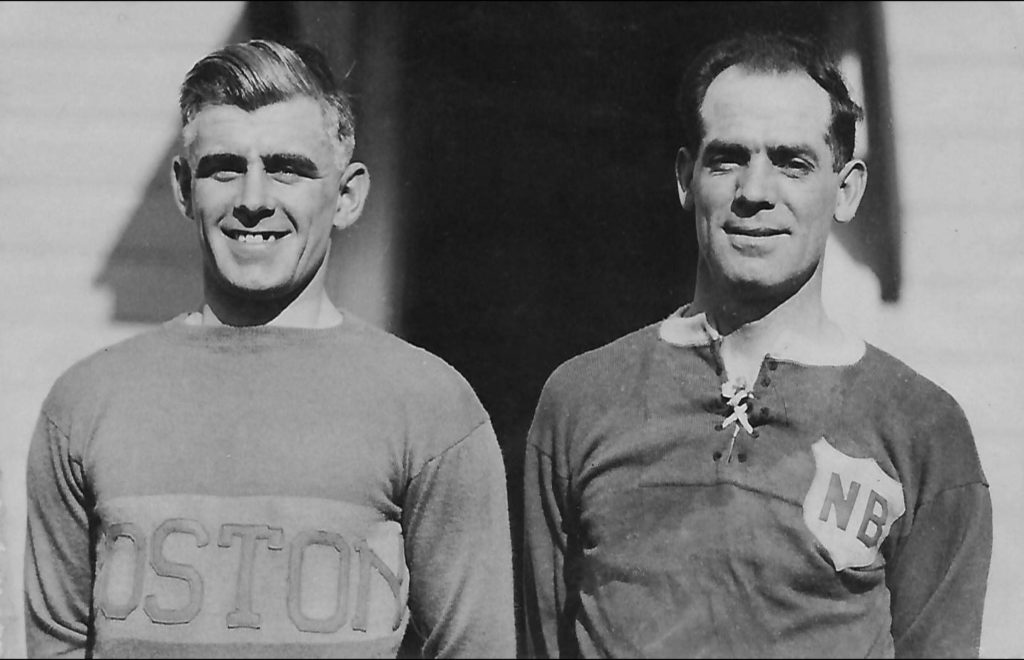

The winger had been approached two years previously by a (unnamed) New England soccer club, turning down that offer, as he explained in the Echo at the time:

‘It is well known to me that some clubs in America are prepared to make quite interesting propositions. A football agent came all the way from near Boston to point out to me the wonder and possibilities of football in the states. Well, I stopped, I looked, and I listened and then I turned down the proposition with the remark that the idea of American football did not tempt me. It will be a very long time before the game in America has such a hold on the people that the clubs will be able to afford fancy prices to such a large number of players that the game in our islands will lose a telling proportion of its best men.’

In 1926, however, he was prepared to play ball. News was released in July that he had signed for Massachusetts side New Bedford on terms described as ‘distinctly attractive’. His move across the border to the USA was held up by red tape, but he reached New Bedford in mid-September.

The new employer competed in the American Soccer League, but won its only honours with Sam when defeating the New York Giants, 5-4 on aggregate, to win the Lewis Cup. In 1928 he was selected for an all-star ASL side to face the touring Glasgow Rangers team. Having graduated to player-manager in 1929, Sam reached agreement to curtail his employment a year early, having made 164 appearances, scoring 21 goals. It was a reasonable goal output, although he told one reporter: ‘The job of the wing-forward in soccer football is to make plays, build up openings by ball control and feed the centre-forward who is assigned to shoot the goals.’

Press speculation in the summer of 1930 was that Sam would be setting sail eastward. However, perhaps with domestic matters in mind, he carved out a new phase of his life in Montreal. He was employed as player-coach of the Canada Car and Foundry Company works team – ‘Carsteel’ – which played at the Stelco Charlevoix stadium and was bankrolled by entrepreneur and soccer advocate Len Peto. [See correction note from Eric Chenoix at the end of this article. Ed]

The winger inspired the side to seven National Soccer League play-off finals, winning in 1936, 1939 and 1940. His final playing appearance came at 50, in the first of four ties with Vancouver Radials in the 1939 national championship final. He had also been selected for the Montréal All-Star team on six occasions. He attributed his longevity to ‘restraint at the table, rather than a strict diet’, smoking sparingly and eschewing ‘spirituous liquors’ entirely.

Hanging up his boots, continued working in the payroll audit department of the steel company until taking retirement in 1954. Perhaps experiencing a void in his life, he returned to the workplace, this time at Burnett Company, stockbrokers, into his early 70s. He lived out his final years at 89 Crescent, Two Mountains, St. Eustache, Quebec, where he was a keen horseman and golfer (his local course was 200 yards from his front door and he had a handicap of 12). Finding the Canadian winters harsh, he would enjoy extended holidays in Florida and other sunspots.

When British clubs were touring Canada, Sam rarely missed an opportunity to meet them and catch up on football affairs across the Atlantic. He visited Everton players in New York, on the Toffees’ 1956 tour of North America – five years later they were based on his doorstep when participating in the International Soccer League in Montreal. Club skipper Tommy E. Jones reported back to the Liverpool Echo: ‘Some of our older fans may remember Sam Chedgzoy in his playing days. He called in on us, and Billy Bingham was ribbed into asking him for some of his advice regarding wing play! Sam played soccer here until he was 50 or more and even to-day (in his 70’s) looks remarkably fit. He asked me to send his best wishes to all Evertonians, in particular Mr. Hughie Stockton, of Eastham, a bosom pal of his in the old days.’

One suspects that there was homesickness in his self-imposed exile. Sam kept in touch with Merseyside by greeting the Liverpool-based crews of Cunard ships (notably the Carinthia) whenever they berthed in Montreal after Atlantic crossings. In 1949 the expat wrote to the Everton match-day programme (in 1949) asking for old friends to get in touch, care of a PO Box address. He mentioned that he was coaching the McGill University soccer team and had even turned out for them several years earlier, when they were a man down. He occasionally wrote to the Everton board of directors, recommending players he had come across in Canada. In 1962, he was able to catch up for six hours in a Montreal hotel with his former Everton clubmate Ernie Gault. Gault, who was over visiting his daughter in Canada, reported back to the Echo: ‘As soon as Sam stepped into the foyer of the hotel, I recognised him. There was something unmistakably Chedgzoy about his step. He looks fine, though, like me, he’s 73 years of age.’

December 1964 saw a remarkable family reunion when Sam’s sisters came together for the first time in six decades. When Frances Chedgzoy died in 1899, the children were distributed among the extended family. Edith was sent to live with an aunt in Montreal, while Sam, Lily and other siblings remained in England. The aunt failed to keep in contact with the family back in the motherland, so Edith had no contact with her siblings – even when Sam had moved to Canada. By chance, in the 1950s, she saw his picture in a local newspaper, so managed to reach her brother via a football referee who told her where to find him: ‘He was at the racetrack so I rushed out to see him and he recognised me because he said I was so much like our sister Lily.’

Lily, meanwhile, was living in London and had spent years trying to reconnect with hr siblings. She reached out through various channels, including newspaper ads resorting and the Salvation Army, all to no avail. Finally, a football agency in Britain located Sam for her, across the Atlantic.’ Arrangements were made for Lily to fly to Montreal, where Sam and Edith were waiting at the airport to greet her off the plane. The Montreal Star reported: ‘The sisters were almost breathless with joy. Mrs Dunn [Edith] was close to tears and Mrs. Jackson [Lily] touched her eyes with her handkerchief and brushed away the tears that streamed down her smiling face. Meanwhile Mr Chedgzoy looked happy and said: “You couldn’t mistake those two for sisters, could you? You’d know both if you saw one of them.”’

Trips back to Britain were rare, due to the family sensitivities; but in 1965, aware that his health was beginning to fail, Sam made one final visit. The itinerary took in Switzerland and France with stopovers in Cornwall and London. In Newquay he had an encounter with Arthur Clough, an Evertonian on holiday from Warrington. Clough told a newspaper: ‘I was sitting in a deck chair and got talking to the elderly chap sitting next to me. I mentioned that I came from Warrington, and, to my surprise, he said that he knew Warrington and around Liverpool very well. Then he said: “I played for Everton for 16 years, so I ought to know the district.”’ In answer to my question, he told me that he was Sam Chedgzoy and that he had come to England from the continent, on vacation from his home in Canada. I was delighted. We had a good old natter about the old days, I can tell you.’

Next was an emotional return to Ellesmere Port. He took the bus from Chester to his hometown, asking a fellow passenger if he could help track down some of the friends from Burnells (the passenger duly obliged). Then he made for the offices of the town’s Pioneer newspaper, to enquire as to the whereabouts of an autographed football that he had sent back in 1939 as a gift to the community. The ball couldn’t be traced at the time, but the journalist subsequently located it in safe hands. Although he caught up with Syd, care had to be taken as Annie lived next door to her son, on Beacon Lane. He passed on a number of items relating to his football career to Syd for safekeeping (the 1914/15 championship medal was not among them).

Back home in Quebec, Sam died from Lung Cancer (he had been a heavy smoker) on January 27, 1967, aged 77, at Queen Mary’s Veteran’s Hospital. Having enjoyed a most illustrious football career, he was one of the first players ten inducted as Everton Millennium Giants, in 2000 (Sam was the Giant of the 1910s, following fellow outside-right Jack Sharp, who was the Giant of the 1900s). Five years later he was posthumously inducted into the Canadian Soccer Hall of Fame.

Syd Chedgzoy

By the time his father emigrated to North America in 1926, Syd had already been indoctrinated in football. From the age of five he was taught key football skills by the doting Sam, and represented his team at high school. He found himself pushed as an outside-right, to follow in the famous footsteps of his father.

After spending time with a junior team in Orrell and New Brighton FC, he was linked with a move to Burscough in the summer of 1929, but Everton moved in. In fact, Syd had nearly signed for Liverpool as a youth – they came in for him and he asked to think about it overnight. The next day, he called to say that he’d like to go there – but they had changed their mind and didn’t want him. His grandson, Gary, mused: ‘I’m quite glad as I wouldn’t want that on the family record. I would never have forgiven him for that.’

It was a tall order to emulate his father, more so at a club at which Sam had legendary status. Although never making a mark at Goodison, he played alongside Dixie Dean, as his father had, albeit in reserve matches. He recalled how it was an impossible task to break through:

‘Folk said, “Is this boy as good as his dad?” I said, “Forget that I’m a Chedgzoy – call me Jack Jones if you like, I want to make my own name.” But every time I went on to the field in my early days, I knew the fans were comparing me with the Chedgzoy they had seen before. I even imagined them shaking their heads! Having to play up to a name, though I was unknown in ability, was bad enough. I also had to do this among folk who knew as much about my dad as I did.

‘As far as league games went, I flopped, for I didn’t even have one, but I made a big discovery. I’d been outside-right before. Now at Goodison I realised I hadn’t what it takes for being a second Sam. I wasn’t fast enough for a winger. I liked playing around with the ball, so right-half was my best shop. I became among a maze of right-halves – I had to line up behind Cliff Britton, Archie Clark, Joe McClure and Lachie McPherson. My outstanding Everton memory was the amazingly high standard of the regulars’ play. The place was stacked out with internationals. I had youth on my side. But I’d have been growing a beard before Goodison could possibly have been good to me!’

In 1933 he transferred to Burnley, coming under the management of former Liverpool star Tom Bromilow, who he rated highly, describing him ‘as quiet as a lamb, but he got more work out of us than a blustering sergeant major could have done.’ That said, he gave Syd the ‘football lesson of my lifetime’ after he had played for Burnley against Stoke City reserves:

‘I’d seen plenty of the ball and seen to it that my mates had a fair share of it, too. Mr Bromilow came to me and said, “You’ve played a shocking game!” I couldn’t believe my own ears. Couldn’t figure out a solitary reason for this slating. Mr Bromilow did. “You were OK with the ball; I’m grumbling about what you did when you didn’t have the ball. I never once saw you cover-up properly. After you’d parted with the ball you usually strolled back to position. You gave the Stoke inside-left half the field to work in. I want you RUNNING about intelligently all the time!”’

Bromilow converted Syd (against his better judgement) back to a right winger, prompting Millwall to sign him in that position, but he found the transition difficult: ‘Struggling to justify Millwall’s faith in me turned me into a bundle of nerves. My blackest of many black games was against Charlton. I had just two kicks at the ball and was dropped the following week!’

His escape from The Den took him back to near home, where he found adulation: ‘I went into non-league football – with Runcorn in the Cheshire League. Happy memory – my play came back to standard again. I was still a right-winger. The relief of getting away from league strain had worked the cure. Of all the clubs I’ve been with, I rate Runcorn the best. A neat little ground, and the cheeriest bunch of players and officials you’ll find anywhere.’

His return to form tempted Alex Raisbeck to sign Syd for Halifax in 1935, but the manager resigned soon afterwards, and, after six weeks without a look-in, it was clear that he had no future at the Shay. ‘What rankled with me was that I honestly thought I was value for first team play.’

Syd returned to Runcorn before crossing the Pennines to join Sheffield Wednesday, making four appearances for the second-tier side. A move to Swansea Town revitalised his career, with him making 18 appearances in the 1938/39 season, starting out as a winger before being redeployed in his favoured right-half role.

The outbreak of war ended Syd’s professional career; he went on to serve as a military policeman in Egypt. The family have retained his records which contain notes about murders, larceny and camels going the wrong way down the road! After the war he was a ticket inspector on the trams in Liverpool and then worked as a wages clerk for English Electric on the East Lancs Road. He passed away in 1983.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to Gary Chedgzoy for making this article possible. Photos are used courtesy of the Chedgzoy family.

Pete Jones kindly assisted with information about Sam’s war record. Chris Goodwin co-curates the fantastic England Footballers Online website, which contains information about Sam’s international playing career.

Sources

Books:

James Corbett, The Everton Encyclopedia

Nick Walsh, Dixie Dean: The Life Story of a Goal Scoring Legend

Ken Rogers, Goodison Glory

Steve Johnson, Everton: The Official Complete Record

David France, Rob Sawyer, Darren Griffiths, Toffee Soccer

Newspapers and Magazines, including:

Ellesmere Port Pioneer

Liverpool Echo and Football Echo

Liverpool Courier

Liverpool Daily Post

The Daily Courier

Daily News (New York)

Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon)

The Montreal Star

Topical Times

Websites:

bluecorrespondent.co.uk (Billy Smith)

evertonresults.com

englandfootballonline.co.uk

Correction

Hello!

Being an Evertonian (chosen, when I grew up in Belgium way back in the 1980s) and part-time local football historian in Montreal Canada, I read your piece on Sam Chedgzoy with great interest. What a ride it was! It helped me have a clearer picture of who Sam Chedgzoy was on and off the field.

I would however like to point out a small mistake in your article. In the following line, you got the location of Carsteel’s home games in 1930 wrong. “He was employed as player-coach of the Canada Car and Foundry Company works team – ‘Carsteel’ – which played at the Stelco Charlevoix stadium and was bankrolled by entrepreneur and soccer advocate Len Peto.” All the info is spot on, but the Stelco Charlevoix Street grounds did not exist in 1930. Carsteel had lost its ground (Thornton Park) two years prior, and was at the time moving from one ground to another every year. In 1930, they played at the National Amateur Athletic Association’s grounds, located in Maisonneuve, a district in the east side of Montreal. The stadium is long gone, but a city park has been built over it many years ago. The land the stadium was located on was sold towards the end of 1930 and the stands and clubhouse were eventually demolished, forcing Carsteel to move. Carsteel will eventually end up at Stelco’s ground, but a few years later (Stelco did not have a team yet in the early 1930s).

Also, a bit of info about your picture of “Sam as a coach in Canada”. This actually is a photograph of McGill University’s team, as the crest of the university is clearly seen on the shirts. So that would date it to the 1940s (a quick search shows me Sam was already coaching McGill in 1942).

Thanks for this fine article and keep up the good work!

Eric Chenoix