It had been just four weeks since the first football knockout competition, won the by The Wanderers, had taken place on the Kennington Oval ground in London, when a boy was born on the South West Coast of Scotland. He was destined to make FA Cup history.

John Cameron was born on 13 April 1872 in the Newton district of Ayr, where his family, who were in the grocery business, had finally come to settle. The 1881 census recorded the business premises on Waggon Road, where John was by then an eight-year-old scholar. He later attended Ayr Grammar School. In 1891, the Cameron family were to be found living on Church Street in Ayr, whille John was working as a Clerk for the Cunard Shipping Company in their office at 30 Jamaica Street, Glasgow.

John Cameron began his football career with a local team who played under the name of Ayr Parkhouse. This club had been formed in 1886 and were playing on Beresford Park when he joined them. They later joined forces with a local rival and became Ayr United.

Around the early 1890s, the name of John Cameron starts to appear in the ranks of the famous Queens Park amateur club in Glasgow, where he formed a left-wing partnership with Willie Lambie. His style of play caught the eye of local agent, Mr R. D. Allan, who alerted Everton Football Club of his ability. Allan was paid the sum of £10 when the player signed amateur forms for Everton.

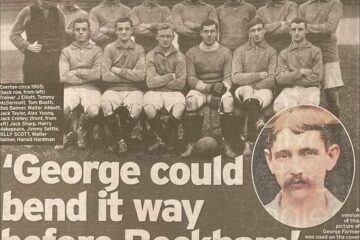

It is not reported in the newspapers of Liverpool when the young Scotsman actually joined Everton, but he was certainly classed as an amateur. He made his debut on 5 October, 1895, playing at centre-forward, but failed to score in 5-0 win over Sheffield United at Goodison Park. When the next Everton board meeting took place on 11 November, 1895 the club secretary was instructed, in reply to a letter from Cameron, to ‘write and say we have promises of situations from friends at £140 to £150 per annum.’

Cameron struggled at first to adapt to the game in England and was frequently replaced by Abe Hartley at the head of the Everton forward line. He finally got on the scoresheet on 14 December 1895 in 7-2 home win over Stoke, and took part in the club’s FA Cup run that ended in a 4-0 defeat by Sheffield Wednesday at the Olive Grove. On 28 March 1896, he won his one and only international cap when he played for Scotland in 3-3 draw against Ireland in Belfast. He represented his country, not as an Everton player, but as a Queens Park amateur. Next season Cameron again signed for Everton.

The Hampden Park directors, however, were anxious that he should retain his amateur status, thus making him eligible for their club but the Scot decided to accept the offer made by Everton and turned professional. His actions prompted a Scottish journalist to write:

Cameron, about whom the Queens Park are making such a fuss, has just signed a professional form for Everton. Cameron has been [used] much as centre in Scotland last year and a vast amount is always heard about his Liverpool brilliancy. He was a member for the leading Scottish amateurs, and the Hampden officials frequently endeavour to get him to play for them in their more important ties. Everton are in a plight with their players. They are trafficking all and sundry and signing anybody they can lay their hands on. They must be paying quite a small fortune in commission to the dreaded agent. (Dundee Courier, 19 November 1896.)

Cameron played his first professional game at Anfield in a 0-0 draw with Liverpool. He then produced his best performance on 28 November 1896, when he scored a hat trick in a 6-0 home win over Burnley. Nevertheless, he lost out to Hartley and took no part in the FA Cup run which saw Everton beaten by the odd goal in five in the final against Aston Villa at the Crystal Palace in London. Next season the contest for places in the Everton forward line further intensified when the club signed Laurence Bell from Sheffield Wednesday.

It is around this time that the Football League clubs – or more precisely their Directors – were attempting to impose a wage restriction of £4 per week and certain players saw this as a threat to their livelihood. Furthermore, the clubs had recently implemented a registration scheme that bound the player to them and forbade him from taking part in any negotiations concerning his transfer. In February 1898, the Association Footballers Union was formed at the Bee Hotel in Liverpool and Jack Bell became the president. John Cameron took on the role of secretary.

The Scot, however, was losing out to the Bell brothers in the Everton forward line and made his last Football League appearance for them on 22 February, 1898 against Sheffield United at Goodison Park. He was then placed in the second XI and made his last appearance for the club in the final of the Liverpool Senior Cup, which resulted in a win over New Brighton Tower at Goodison Park. When the outcome of the Everton AGM was published on 3 June, 1898 the name of Cameron was not amongst the players who had been chosen to represent the club in the next season. He had played 42 games for Everton and scored 12 goals.

The news quickly reached ears of former Everton player Frank Brettell, now the manager of Tottenham Hotspur, who signed the Scotsman one week later. Everton were asking a fee of £500 for his transfer. Cameron completed his first his season as Spurs finished in seventh place behind Southern League champions, Southampton. The Londoners were in the process of leaving their old home at Northumberland Park for White Hart Lane when Frank Brettell suddenly left the club and joined Portsmouth. The Tottenham directorate immediately offered the vacant position to Cameron who returned to Merseyside and signed Jack Kirwan and Ted Hughes from Everton.

The Scot was now the player-manager and secretary of the London club and he appointed former Bootle player Jackie Jones as club captain. Next season Spurs won the Southern League title for the first time and one year later on 20 April 1901 they appeared in the final of the FA Cup. It had been eighteen years since a London based team, Old Etonians, had reached this stage of the contest and an enormous crowd of 110,820 people flocked to the Crystal Palace Grounds to watch Spurs fight out a draw 2-2 with Sheffield United. It had been previously arranged that should the game end all square, the replay would take place a Goodison Park in Liverpool. However, following an objection from Liverpool Football Club, the decision was made to stage the game at Burnden Park in Bolton.

The occasion failed to capture the imagination of the football public and just 20,470 spectators were present to watch John Cameron score one of the goals that helped Tottenham Hotspur win the game by three goals to one. The Londoners thus became the first team from outside the Football League to lift the trophy. When the season came to an end, Cameron returned to his native Scotland in order to be married.

The lassie of his choice was Grace Steele who had been born of Scottish parentage in Southampton in 1872. Sometime around 1895 the Steele family returned to Ayrshire where they occupied Polquhirter Cottage on the three-hundred-acre piece of farmland that belonged to her mother’s family. It appears that she became a woman of leisure for she lists her occupation on the marriage certificate as that of an artist. She married John Cameron on 25 June 1901 and the ceremony took place at “Lochlea”, Castle Hill Road, Ayr. This was the home of Grace Steele, while her husband resided at 27 Willowby Park Road, Tottenham.

The couple then moved to London and appear on the 1901 census living at 25 Baronet Road in Tottenham. There was soon further cause for celebration in the Cameron household for records reveal that a daughter, Mary Hunter Cameron, was born and later baptised on 4 May 1902 at the local Presbyterian church dedicated to St John. The Scotsman remained at White Hart Lane until he left the club in 1907 following dispute with directors. One year later he published a book under the title of “Association Football and How to Play It”.

The 1911 census found the Cameron family had moved to the Rochford area of Essex where the head of the household declared himself to be a journalist living by his own account. The census form also revealed them living in two rooms at Old Three Ashes, Sutton Road, Eastwood. Sometime later John Cameron took up a position as football coach at Dresdner Sports Club in Germany, and was there at the outbreak of World War One. He was then taken in to custody, along with around four thousand other British subjects, and interned at Ruhleben Civilian Prison Camp on the outskirts of Berlin.

Amongst the inmates were several other ex-professional football players who had also been coaching in Germany. The most famous of them was Steve Bloomer. There were another three former Everton players, the largest number from a single club held in Ruhleben. They were: Walter Campbell, Stanley Wolstenholme and John Brearley. The manner in which these British subjects coped with captivity is well documented and needs no further explanation here. However, a number of letters, written by John Cameron, give some insight in to the hardships involved and how they longed for their freedom. The first of these letters appeared in the national newspapers, September 1915, under the heading of “A Letter from an Interned Footballer” and was addressed to F.J. Wall, the Secretary of the FA…

All lovers of football here, send you greetings. I am glad to say that things are now better now than in the early days of our captivity, a time I will not dwell on. The first gleam of sunshine came about the middle of March, when we were allowed a part of the racecourse for recreational purposes; we quickly made two pitches and formed Ruhleben Football Club… of which Fred Pentland, Small Heath, became president and I myself was made secretary. We had a hurricane season of six weeks – two league games and one cup competition, with friendlies etc. We played over three hundred games in that short time, I fancy that is record.

John Cameron wrote a second letter home and this was published on 13 August, 1916 in the Sunday Post. It reveals how frustrated the inmates now felt about their captivity and that their situation was not improved by the news they received from home…

Our constant cry is “How Long?” and we get utterly sick of each other at times. Must we be here for another football season? Our boys here sometimes get dreadful shocks of a brother who is dead or wounded. One young chap called Eden is now a baronet through a series of deaths. We have nephew of the great Balfour also in our “big run” and the Earl of Perth is also in the camp.

What these letters do not reveal is that John Cameron is also bereaved by the loss of his wife on 5 March 1915 at 20 Marshfield Road, Ayr. The death was registered by her brother-in-law, Kenneth Cameron, who confirmed that his brother also resided at that address and his occupation was that of a clerk.

John Cameron, following his release from Ruhleben, took up residence at 60 Church Street, Ayr. In 1918 he became Manager of Ayr United, but decided to leave the job after just one season in charge. He later settled in Edinburgh where he spent the final years of his life working as a shipping clerk. Cameron was living at 303 Easter Road, when he died on 17 April 1935 and was cremated at Warriston Crematorium. He was 63 years old.

Follow @EvertonHeritage

Follow @EvertonHeritage